Navigating challenging times

Chapter two

Change is a constant – and it is positive. Change causes us to innovate and evolve as we adapt to risk and opportunity. But change can also bring discomfort as we are forced to grapple with uncertainty and complexity, and, by definition, brings disruption.

The period ahead brings significant, multi-faceted and accelerating change, making our current assumptions and frameworks for decision-making less and less valid. New opportunities will open up too, and we need to have the right capabilities to notice and take advantage of these.

Complexity arises from the reality that we are always seeking to balance many goals and objectives in a system with many interacting parts. Sometimes, our objectives are simple, but the solutions are complex – a goal of reduced emissions is simple but getting there is not. Other times, the solutions are simple, but the objectives are complex – we don’t have a consensus on social agenda objectives, for example. Uncertainty means many future states are possible, and the pathways to those future states are hard to predict or quantify. A complex system with many unknowns results in unforeseen consequences – disruption. The actions we expected would deliver one result may deliver something quite different, our trajectory does not play out as expected, and new challenges are thrown at us that we must find the capacity to respond to.

This environment creates a specific set of challenges: around the choices we make and our ability to follow through on those choices with execution.

Challenges with choosing relate to our ability to make the right choices – what we choose to deliver, what risks to manage, what realities we need to accept, what opportunities to leverage, the issues to be prioritised and what responses will be most appropriate. Do we scale solar or wind energy? Do we build on greenfield or brownfield sites? Do we cultivate aerospace or agriculture? Can we find a way to do both?

Challenges with execution relate to our ability to execute our choices in the face of shocks and changing contexts – how we respond to risks and issues, how we deliver on our commitments, and how we stay motivated and effective in the face of consistent change and rolling crises.

As uncertainty increases, there is an interplay between choice and execution – we need to respond to changing contexts and be able to quickly test and update our choices, as well as make our execution approaches more agile to change. This doesn’t come easily. We know shocks will keep coming; to be successful, we must strengthen our ability to navigate complexity, uncertainty, and disruption.

Deloitte Director, Cassandra Favager on the challenging future ahead

Why is this context so challenging?

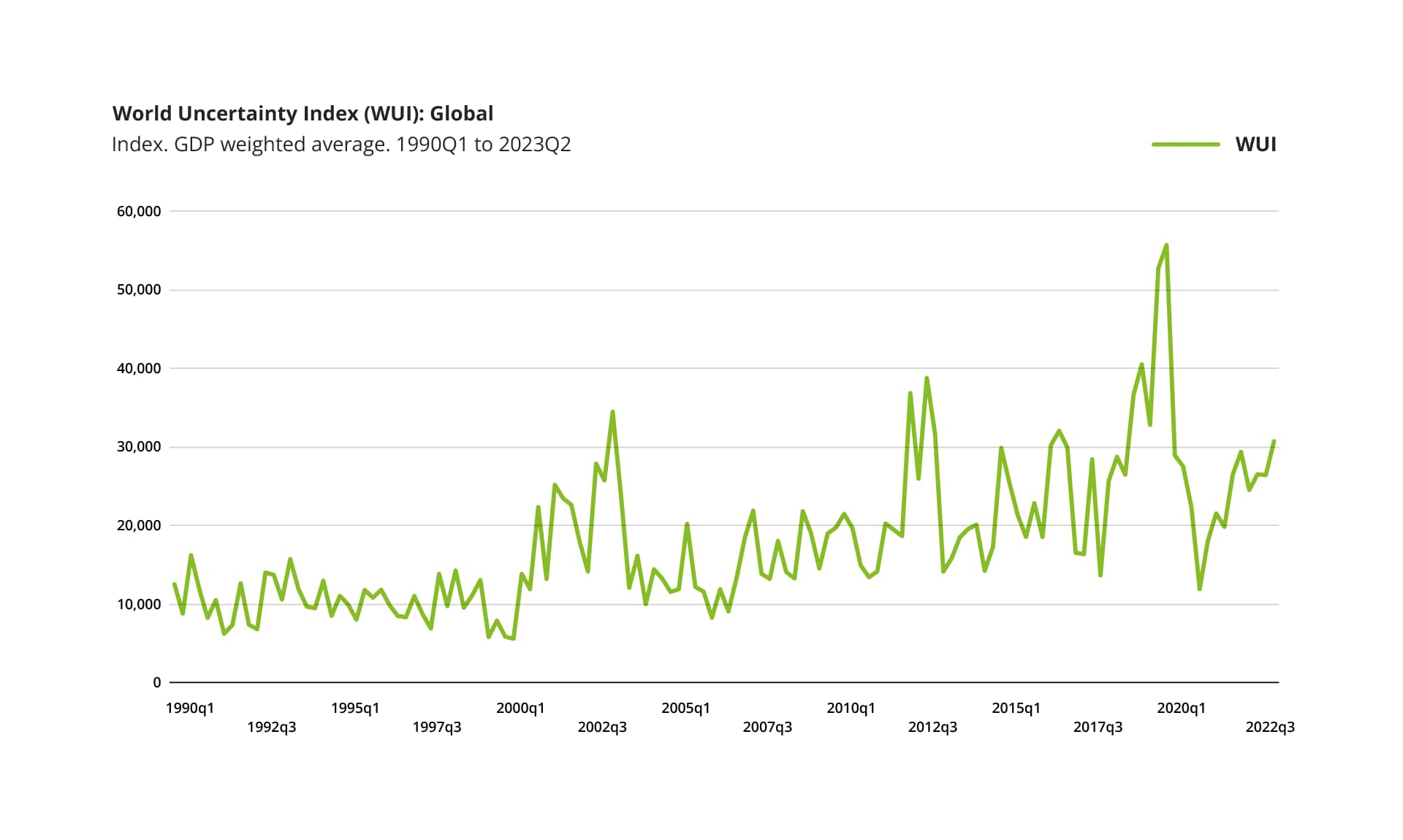

It might be hyperbolic to talk of ‘unparalleled uncertainty’ – uncertainty is always with us. The World Uncertainty Index paints a picture of peaks and troughs – not surprisingly peaking in 2020.1 But the overall trend is upwards and uncertainty is an increasingly pervasive backdrop. The challenges facing us are multi-dimensional and, in some cases, existential. It is useful to reflect on why we find uncertainty so challenging.

Humans seem to be hard-wired to find complexity and uncertainty uncomfortable. It threatens our need for control and stability and can feel frustrating and disempowering. Instead, we prefer certainty over probability (Prospect Theory)2 and known courses of action over new ones (habits).3 Because of our preferences, we often struggle to make decisions in the face of complexity and uncertainty. We don’t feel we have enough data and clarity, and we don’t have sufficient confidence that we are making the right choice.

We have a serious loss aversion (the pain of losing is twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining), and in these circumstances, we succumb to decision paralysis.4 Even though deferring a decision carries consequences and risk, we are more likely to wait or to prolong our considerations – the organisational snare of analysis paralysis, and the individual challenge of choice overload.

Foundationally, we struggle to understand and accept complexity and uncertainty. We have built tools to interrogate and quantify risk, but conveying uncertainty as a ‘1 in 70 chance’, a percentage likelihood or a range, is still too abstract for most of us.5 And sometimes, we struggle to know what the right question is.

When we do act, we see challenges that constrain our success. Disruptions will continually challenge our ability to stay on course. When our assumptions don’t hold and our context changes, whether through disruptions or unforeseen consequences, we struggle to pivot to our new reality. This means actions may be abandoned completely, or we may deliver the solution as planned despite it no longer being able to achieve the desired outcomes. This is particularly relevant in infrastructure, which is so long-lived that mistakes are often baked in early. We often apply the wrong approaches to the context – linear programmes of work in complex systems, paint-by-numbers programmes when we are, in fact, walking in the fog. Either way, the benefits of our investments are not realised.

The context also creates the possibility of desirable outcomes (opportunities) as well as undesirable ones (risks). Pursuing these opportunities – through disciplined innovation, calculated risk-taking or good fortune – can leapfrog us into more desirable futures.

But people also find it hard, even uncomfortable, to visualise a significantly different future from their today. Whether from a lack of reference points, or an absence of objectivity or imagination, we tend to start from where we are. For most people – even those with deep experience in their fields – visualising a possible future without first-hand experiencing precedent is the realm of science fiction. Nikola Tesla provides us with a rare example, predicting what we would recognise today as a smartphone a hundred years ago.

"When wireless is perfectly applied the whole earth will be converted into a huge brain, which in fact it is, all things being particles of a real and rhythmic whole. We shall be able to communicate with one another instantly, irrespective of distance. Not only this, but through television and telephony we shall see and hear one another as perfectly as though we were face to face, despite intervening distances of thousands of miles; and the instruments through which we shall be able to do this will be amazingly simple compared with our present telephone. A man will be able to carry one in his vest pocket.”6

When we look ahead, we see that those who are best prepared to identify emerging trends, see the opportunities within them, and take advantage, can come out on top. This can play out positively – when societies and communities work together to benefit from opportunities – or can exacerbate inequities when privileged groups are better placed to take advantage of change. We will need to be deliberate in the strategic capabilities we develop to respond to risk and opportunity if we are to create equitable outcomes for all.