Bringing choice & action together

Chapter seven

Choice and action sound sequential: we consider our options, pick a path, and then walk it. But in a context of uncertainty and complexity we must continue to choose anew as we acquire information about results, revalidate and re-evaluate what we thought to be true.

Navigating uncertainty requires us to create structure and direction where it doesn’t currently exist so that we can make ongoing choices, take action and course-correct. Our kuaka, adapting to unpredictable weather conditions and changing landscapes along their migratory route, constantly amend their flight path – testing the efficacy and safety of their new route and charting a new course as they go, while staying true to their destination.

Capability 7: Learning through choice and action

The ability to respond strategically in complexity will close the gap between choice and action, creating momentum for change and more fit-for-purpose interventions long term.

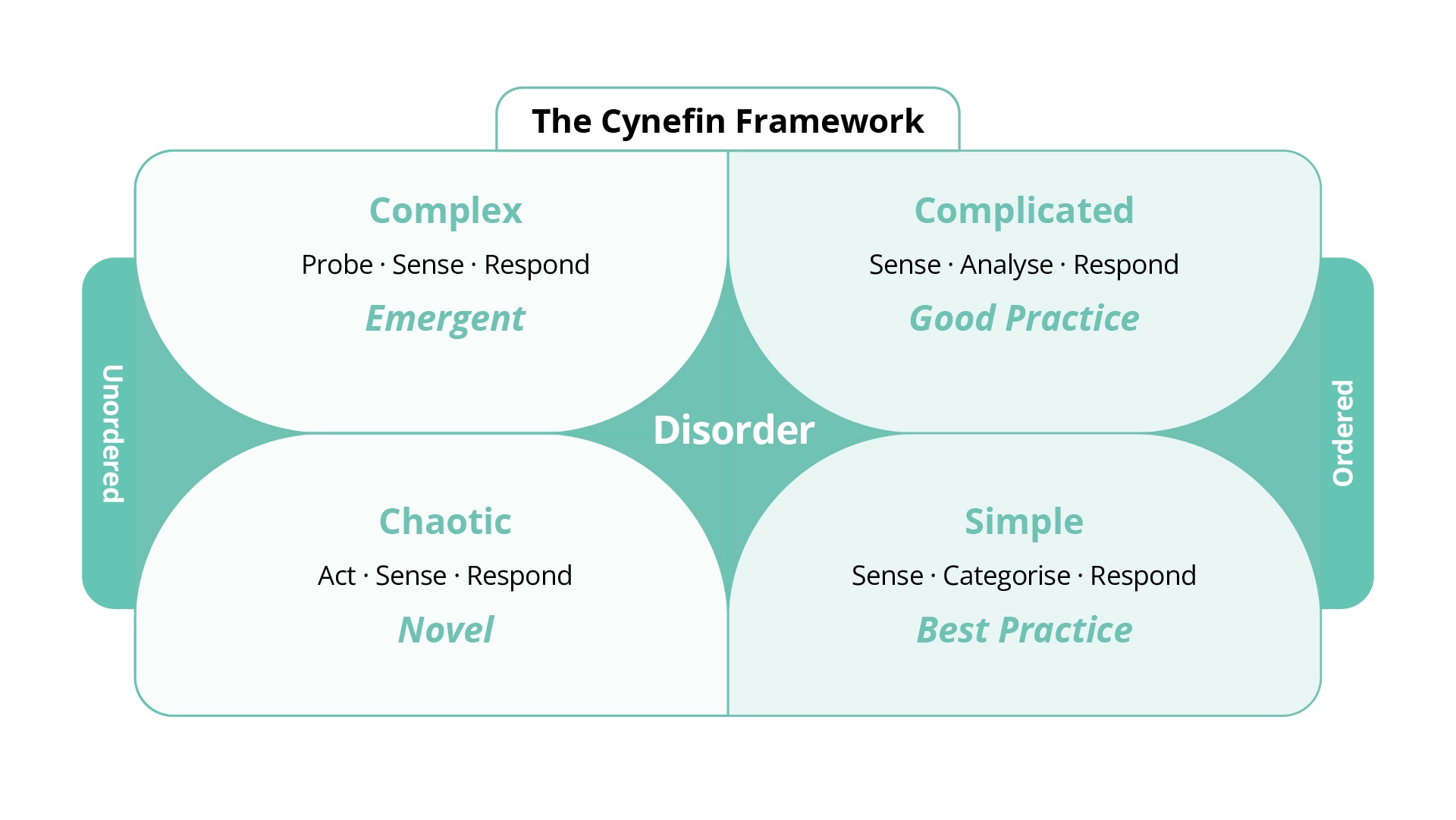

The Cynefin Framework describes five conceptual domains which require different approaches to decision-making.72 In the ordered domains there is a clear relationship between cause and effect, and one or more ‘right’ solutions exist. We tend to be more comfortable in this territory; we analyse the problem and respond with best practice (the answer) or good practice (an answer). The unordered domains are characterised by unpredictability and incomplete data. Here the relationship between cause and effect may only be understood with hindsight (if at all).

The complexity, uncertainty, and disruption we face most closely resemble the complex domain, in which cause and effect do exist but are hard to spot, and it may be impossible to identify a ‘right’ solution. When we are used to operating in ordered domains, this can be paralysing – taking no action feels safer than taking actions we are not confident in, and we stay in ‘define and analyse’ for too long.

In this domain, the strategic response in the Cynefin framework is to probe, sense and respond – test or search our coherent ideas for action and run parallel safe-to-fail experiments to reveal what is possible. In combination, the experiments change the system (rather than simply succeeding or failing) so that things are easier to manage.

Realistically these kinds of experiments are rare. Where we cannot know what will work strategic flexibility is a more pragmatic approach. Strategic flexibility is not ‘wait and see’, but intentionally understanding what scenarios may play out, what actions we can take that best support multiple pathways, and how to shift to an alternative pathway where that is more likely to achieve our objectives. This way we take the best actions we can while intentionally keeping our options open as things change or become clearer. Originating from the field of climate change, Dynamic Adaptive Policy Pathways are one approach for doing this that is gaining some traction in Aotearoa.

Core to strategic flexibility is the ability to think at a system level, and a learning culture. Developing our capability to operate in complexity starts with the ability to think about and make sense of systems, the forces that shape them and the interconnections that hold them together. Learning and making sense of complex systems brings together broad sources of insights to understand the health of the system. By recognising patterns, behaviours, and motivations, we can better assess how our interventions may have intended and unintended consequences. We also recognise the partnerships and collaboration that are required to create alignment across many parties.

Culture and practices of learning underpin complexity responses. Without the ability and willingness to course correct – and the readiness to fail – actions will be pursued because we have committed to them, not because they are likely to deliver the outcomes that we set out to achieve. Delivery agility must be supported by governance agility to be able to pivot without sacrificing long-term accountability to achieve our goals.

All of this is challenging in the public sector where decisions are subject to public scrutiny. It asks for organisational and political bravery to act without knowing everything and to consciously accept that we will make choices that we will need to change. An informed public that understands complex responses are critical to creating an environment where this is possible.

Cassandra Favager on the strategic capability to learn through choice and action