Six workforce strategies to plan for a future you can’t predict

The first in Deloitte’s series on the future of workforce planning explores how leaders can shift from planning for the future to preparing for many possible futures

Sue Cantrell

Kevin Moss

Russell Klosk

Chris Tomke

Zac Shaw

Michael Griffiths

Uncertainty and volatility have become defining features of today’s world—not just as talking points among executives, but as daily realities they’re forced to navigate. The World Uncertainty Index has remained elevated since 2015. Surveys from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the Conference Board show that leaders remain cautious, and Deloitte’s own CFO Signals surveys consistently rank risk, uncertainty, and inflation as top concerns. Even earnings guidance tells the story: Since 2020, S&P 500 companies have shown greater variability in forecasts, with many firms using cautionary language or abandoning guidance altogether. United Airlines made the news, for example, when it issued not one but two profit scenarios, calling both the economy and its own outlook “impossible to predict.”1

The only thing we can know for certain about the future is that it’s unknown—and that’s a fundamental challenge for workforce planning, which has traditionally relied on stable assumptions, linear forecasts, and multi-year roadmaps built on the belief that past trends can reliably predict what’s next. Large organizations may spend half a year planning for the next, making high-stakes decisions based on assumptions that may not hold true for long.

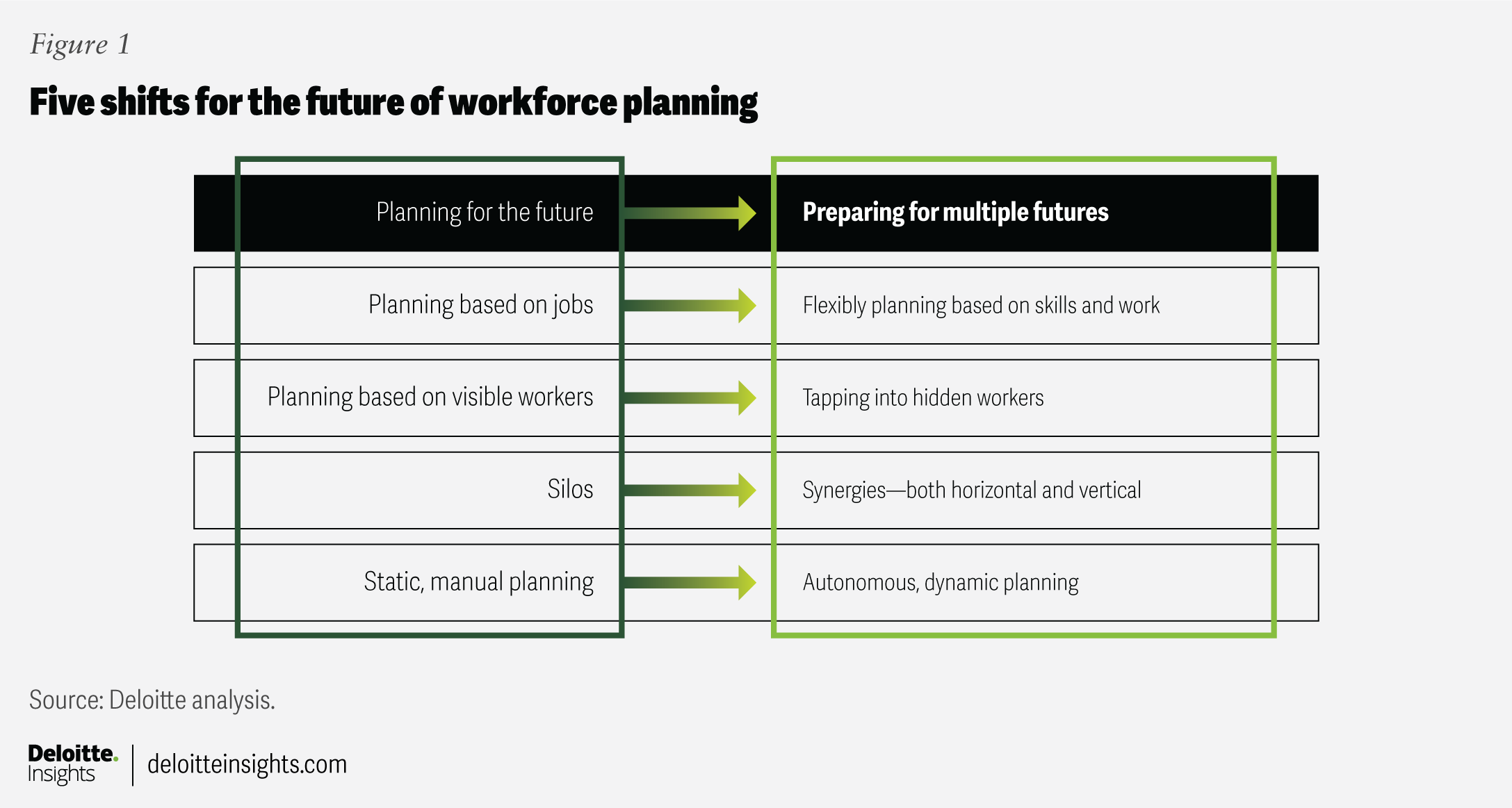

How can a company plan for its workforce when it may not be able to trust its own assumptions? Tackling this challenge requires organizations to embrace uncertainty—shifting from trying to plan for the future to preparing for many possible futures.

When the future seems impossible to forecast, the advantage shifts from those who predict well to those who adapt and decide well. Strategic workforce planning, an evolution of traditional workforce planning that we discussed in the introduction to this series, isn’t about charting a single path forward, but about leveraging available data to make confident, high-velocity decisions in an environment where no one has a map.

That means rethinking workforce planning from a static, one-and-done exercise into an ongoing discipline of testing, adjusting, and reallocating in real time. We’ve identified six levers that leaders can use to build workforce agility, stress test decisions, and strengthen the human capabilities that will hold their value regardless of what the future brings. In this article, we’ll explore how some organizations are leveraging new methods and borrowing approaches from other functions to create new workforce planning approaches for an age of uncertainty.

Plan for multiple scenarios

When we can’t plan for the future, we can plan for potential futures to uncover strategic opportunities and directions. When paired with the relevant key performance indicators, those futures can be modeled to assess potential impacts—both for the workforce and businesses they support. Organizations have long used methods like scenario planning to stress test different courses of action and assess risks; newer technology can help enable more advanced and flexible projections by incorporating a broader scope of uncertainty.

One example of this approach comes from Edie Goldberg, founder of E.L. Goldberg & Associates and a specialist in talent management and organizational effectiveness. She points to her scenario planning work with MyoKardia, a fast-growing biotech firm (later acquired by Bristol Myers Squibb).

Around 2018, the organization projected about 30% annual growth in anticipation of its first FDA-approved product, but faced major uncertainties, including clinical trial outcomes and alliance partnerships. Leaders also considered broader trends shaping the future of work, such as technological empowerment and the democratization of work. Based on these factors, MyoKardia’s leaders developed four potential future scenarios, ranging from status quo to highly disruptive, and identified KPIs to signal which scenario might be unfolding. Quarterly reviews helped them stay responsive.

Instead of solely focusing on jobs or headcount, the plan focused on organizational capabilities. Leaders mapped which skills would grow in importance or become less relevant in each scenario, in conjunction with a capability gap analysis. Labor market analysis of remote work, skill scarcity, and geography informed time-to-hire estimates, shaping “build, buy, borrow, or rent” talent strategies and a five-year staffing forecast, which was aligned with financial and space planning.

The payoff of this approach came when a key alliance dissolved: MyoKardia was able to quickly pivot to an alternative scenario leaders had already planned for.2

Model decisions with a digital twin of the workforce

Planning for uncertainties can also involve a broader set of tools than scenario planning. Some organizations are experimenting with building digital twins of their workforces—replicated scenarios or live models of a workforce.

In the past, operational use cases were the most attainable and actionable frontier for digital twins. For example, using a digital twin to mirror a physical piece of machinery on a factory floor could help workers assess the health of that machine or simulate supply chain management so they could optimize production and cost efficiencies. But advancements in technology, such as the emergence of generative AI, increased cloud computing power, and greater access to data has created new prospects for using digital twins beyond their traditional use cases to simulate workforces, not just physical environments.

Using digital twins for workforce planning applications can help organizations test and model decisions without affecting the actual people and systems. Utilizing digital workforce twins can also enable leaders to model organizational moves and workforce planning more rapidly, helping to keep pace with an ever-changing market.

Outsourcing providers are now exploring digital twins of the workforce, simulating behavior, skills, workflows, and productivity patterns using AI, machine learning, and analytics. This advanced approach has been put toward improving decision-making, predicting staffing needs, modeling workflow changes, analyzing performance impacts, and simulating crisis or change scenarios.3 In the future, organizations could seek to collect data from workers passively as they work (with their permission and with responsible use of data) to generate more sophisticated digital workforce twins to better model potential future impacts of changes like geopolitical changes influencing labor availability or cost or the introduction of agentic AI on skills, headcount, tasks, and more.4 They could also interface with AI-generated “smart KPIs”—KPIs powered by AI that are more intelligent, adaptive, and predictive—to dynamically model workforce impacts as KPIs change.5

Another organization recently leveraged a digital twin sandbox to navigate complex workforce planning decisions. By integrating its internal workforce data with external labor market insights, the organization was able to simulate the effects of various strategies—including increased AI investment, changes in outsourcing, and shifts in location strategy—on talent needs and organizational structure. This approach enabled leadership to assess the long-term implications of different scenarios and confidently prioritize initiatives. The sandbox, developed in collaboration with Deloitte, proved instrumental in aligning workforce capabilities with evolving business objectives.

Many researchers are also exploring new ways to create and apply digital twins of the workforce. Tianyi Peng of Columbia Business School examined how large language models could help create AI agents that mimic human behavior, and Lydia Chilton of the Columbia University School of Engineering and Applied Sciences investigated how AI agents can mirror the often-unpredictable behavior of people in complex situations.6

Make more futures

How else can organizations prepare for multiple futures? The best strategy, according to David Weinberger, author of Everyday Chaos: Technology, Complexity, and How We’re Thriving in a New World of Possibility, “often requires holding back from anticipating and instead creating as many possibilities as we can.”

His imperative for an increasingly complex and unpredictable future? “Make. More. Futures.”7 This approach collapses strategy with execution—letting experiments executed on the ground inform an emergent strategy.

Take Chinese appliance maker Haier, for example. Instead of creating a single strategy and creating workforce plans to support it, Haier runs a series of experiments through a network of autonomous teams—microenterprises that function like startups—continually testing what resonates in the market. Some experiments are expected to fail, which spreads risk and enables the organization to make quick pivots to the experiments that are succeeding. When a winning idea emerges, workers’ skills can be rapidly redeployed to the teams driving it, creating built-in resilience.8

In terms of workforce planning, this means that Haier takes an emergent approach. Instead of forecasting specific jobs to fill, or even what work will be done, the focus is on building a set of adaptable skills and capabilities that can be dynamically redeployed across microenterprises as opportunities shift.

Leave room to move

What happens to workforce planning when the truly unpredictable happens? Consider, for example, how workforces were affected by the pandemic or the recent global trade uncertainties. What else can organizations do when they can’t model potential shocks or trends? In an increasingly volatile world, workforce planners may need to build slack—extra capacity or time—into their work and workforce planning to enable the ability to quickly shift resources into the system and react at speed. In essence, slack allows organizations to prepare for disruptions even when the exact form of the disruption is unknown.

Extra capacity, or slack, is rarely built into workforce plans, which tend to assume people will work at full capacity and utilization, leaving little to no room to accommodate change and disruption.

Slack has long been built into the supply chain and inventory management to buffer against unexpected shocks, disruptions, or delays. It’s a time-tested strategy used to manage uncertainty and enhance resilience (though it needs to be managed carefully to avoid pitfalls of inefficiency and potential higher costs.) But extra capacity or slack is rarely built into workforce plans, which tend to assume people will work at full capacity and utilization, leaving little to no room to accommodate change and disruption. We explore the issue in our 2025 Deloitte Human Capital Trends report, where we report that while 82% of survey respondents say it is important to free up worker capacity, only 8% are making great progress.9

Some organizations are experimenting with building in time and space for slack in their workforce planning. Belgian company DPG Media, for example, schedules only 80% of a team’s capacity with work. What do they do with the remaining 20%? Nothing. The buffer is meant to give workers the ability to accommodate any unexpected issues. If worker utilization was maximized at 100%, DPG says, unexpected work would lead to excessively long workdays and hours of overtime.10

Enabling the ability to adapt more quickly to a rapidly changing environment can benefit the workforce and the organization simultaneously. Improved worker well-being, for example, often leads to improved retention and business outcomes. In our 2025 survey, workers listed flexibility, well-being, time off, and learning new skills—all of which are facilitated when organizations create slack—among the top 10 motivations that drive them to perform at a high level.

Moreover, as work becomes increasingly augmented with AI—and in some cases, replace entire aspects of work—the workforce is likely to invest more time in work that requires critical thinking, innovation, collaboration, and meaningful human interaction. By building in time for such activities, organizations can not only improve engagement and reduce the potential for job-related burnout but also create an environment where the future workforce can flourish and achieve its full potential. Reclaimed capacity can benefit both workers and organizations: One does not need to come at the expense of the other.

Manage talent like a finance portfolio

Volatile markets and businesses require proactive risk management, a discipline that has long been used in finance. According to thought leader, professor, and author John Boudreau, workforce planners could borrow models and frameworks from finance to take a portfolio approach to workforce planning.

Investment portfolios build in balancing for shocks, knowing that one investment may go up while another may go down. The equivalent in workforce planning may be to have multiple types of human capital in a “portfolio”—global and US workers, for example, people and AI, external workers and employees, and skills that are balanced based on their transferability or consistency. Transferable or foundational skills like problem-solving and emotional intelligence could be treated like cash; they are liquid and can be deployed at will. With a little upskilling, these capabilities can be repurposed as needs change.

But just like the stock market, you should balance your skills portfolio with specific skills that may very well rise or fall in demand. Organizations can also consider creating a “line of credit”—in this case, external talent platforms that have people from outside the organization ready to be deployed at a moment’s notice. In this way, planning for the workforce becomes less about planning for specific workforce needs, and more about planning around a portfolio that can better withstand shocks in an uncertain future. This can be an important risk mitigation strategy, enabling greater resilience.

Another useful workforce planning tool from the finance world may be to adopt a “real option” approach, which presents a way of valuing workforce-related decisions based on the flexibility they offer to adapt to future uncertainties. In finance, real options give decision-makers the option to expand, delay, abandon, or modify a project based on how future conditions unfold (unlike other kinds of options, which are tied to securities like stocks).

When applied to workforce planning, the concept of real options can help organizations manage uncertainty and make strategic decisions about their workforce. For example, if an organization anticipates growth but is uncertain about the timing, it can hire employees on a contingent basis or invest in scalable workforce solutions. This gives the company the “real option” to expand the workforce quickly when demand increases without committing to full-time hires prematurely.

Double down on human capabilities

With hard skills having an increasingly shorter shelf life, organizations seeking greater agility and adaptability may increasingly need to plan not only for skills, but for human capabilities too—qualities like curiosity, imagination, judgment, and critical thinking. Geopolitics, business, industries, and jobs are changing so rapidly that it’s virtually impossible to predict the skills employees and leaders will need even a few years out. The question now is not whether people have the right skills; it’s whether they have the potential to learn new ones.

Despite near-universal recognition of the growing importance of human capabilities in the workforce, few workforce plans incorporate planning for human capabilities, possibly because they are harder to measure and quantify than hard skills like data analysis or graphic design.

One multinational technology corporation shifted from a “know-it-all” culture to a “learn-it-all” culture, incorporating human capabilities like continuous learning, collaboration, empathy, and adaptability into talent development and strategic workforce planning, leveraging data and internal platforms to track trends in emerging skills. Continuous learning and curiosity are seen as critical in preparing employees for evolving roles in light of AI.11

Strategic workforce planners at Canadian financial services organization ATB identified the key skills for the future of the bank. In addition to skills like proficiency in AI and automation, business acumen, and client centricity, the majority of the skills are human capabilities like strategic thinking, problem-solving, creativity and innovation, ethical reasoning, and experimentation and learning.12

Human capabilities not only help organizations adapt, but as AI and new technologies become better at replicating the functional and technical aspects of work, they help the organization differentiate. This places a premium on qualities like curiosity, empathy, and imagination.

And, as the traditional concept of “the job” evolves into the broader “work role” (a topic we explore in depth in the next article in this series), workers will likely need not only technical skills but also other characteristics like emotional control, adaptability, integrity, and initiative—what organizational psychologists Andrea Fischbach and Benjamin Schneider call “professional behaviors.”13 Strategic workforce planning, they contend, must go beyond forecasting skills and include fostering a culture and climate of professionalism, where workers at all levels internalize a sense of responsibility, ethical conduct, and autonomy in how they approach their evolving roles. These professional work styles are not optional or peripheral, but essential to effective performance and engagement in today’s ambiguous and fluid workplace.

From strategy to execution

Pulling these levers in the real world is about understanding how and when to use them. That requires more than a workforce plan on paper. Cross-functional expertise, real-time awareness of shifting conditions, and the discipline to adapt as assumptions change are key to moving from strategy to execution. Leaders who want to do this well should focus less on chasing perfect numbers and more on reading the signals—combining quantitative insights with qualitative context to see the bigger picture. With that mindset in place, here are some practical ways to make each lever work harder for your organization.

- Know where the expertise sits. In planning for multiple scenarios, the individuals and teams doing workforce planning should know how to adjust a model and their projections. But organizations need experts from across the business to know what to plan for—the work requirements, the necessary technology, and other myriad factors in play.

- Focus on direction and trends, not hard numbers. Realistically, no one can predict the future, so you’ll never have accurate numbers. Instead, focus on big shifts, trends, and general direction. Don’t worry about precision at this stage.

- Include qualitative data, not just quantitative. Numbers never tell the whole story, especially when considering the future. Context is king; it tells us what to care about and gives the numbers meaning. Interviews, workshops, roundtable discussions, focus groups, and more can all be very useful in providing this context.

- Update assumptions regularly. When using modeling or scenarios, it will be important to regularly update assumptions and revise recommendations accordingly.

Leaders may not be able to control the future, but they can control how ready their organizations are to act when it changes. In a world without a map, success will likely belong to those who navigate by the signals they see rather than the plans they once made.