Reinventing workforce planning for an AI-powered, uncertain world

How can workforce planning become a key differentiator? These five shifts highlight new ways for organizations to think about workforce planning when the only known is the unknown.

Sue Cantrell

Kevin Moss

Russell Klosk

Chris Tomke

Zac Shaw

Michael Griffiths

Uncertainty is a defining challenge for business leaders today. Rapid technological innovation, economic uncertainty, regulatory changes, evolving workforce demographics, and fluctuating skill demands—every day seems to bring both new opportunities and new challenges.

In this environment of constant change, traditional workforce planning—where leaders set strategic direction and other functions, such as finance teams, predict future headcount and skills—may no longer be enough to stay competitive. Few organizations are confident in their approach to strategic workforce planning; only 29% of chief human resources officers in a Gartner survey said they are confident in their ability to deliver on strategic workforce planning goals.1

Workforce planning is evolving—and in some organizations, being reinvented—to become a key differentiator in a dynamic, artificial intelligence-powered world.

The ability to effectively balance and integrate the use of technology and humans, while developing a culture that encourages quick action, can enhance worker and business outcomes. Moving forward, an organization’s true competitive advantage will likely lie in how it flexibly and fluidly deploys human capacity and capabilities, aligning people with work that improves outcomes for both.

Strategic workforce planning is an evolving approach that uses data to align the work that needs to be done with the supply of talent (and automation) available to do it. The goal is to help ensure the organization has the right people, with the right skills, in the right place, at the right time, to deliver on current and future business outcomes.

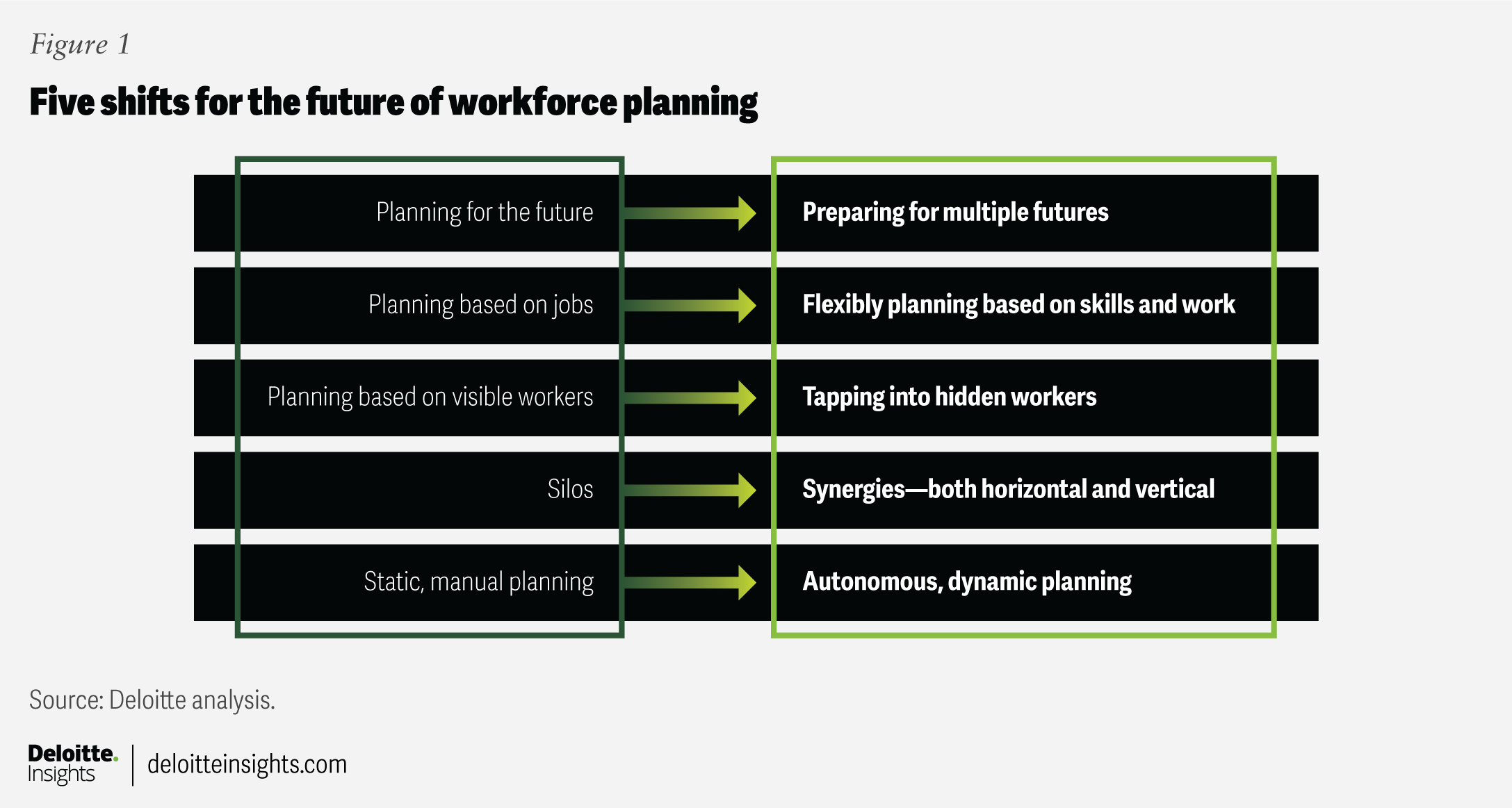

While the intent of workforce planning remains the same, five key shifts are transforming how workforce planning is done, turning it into a competitive advantage for a new world of work. Our series on the future of workforce planning will explore these shifts in detail: creating an adaptive workforce planning capability in the face of uncertainty; focusing on work and on a combination of capabilities embedded in people and AI rather than on jobs and headcount; unlocking hidden capabilities and capacities; embracing autonomous, dynamic planning with AI; and breaking down silos through cross-functional collaboration and democratizing workforce planning data (figure 1). Together, these shifts offer a forward-thinking approach to reimagining workforce planning for the future of work.

A new approach to workforce planning

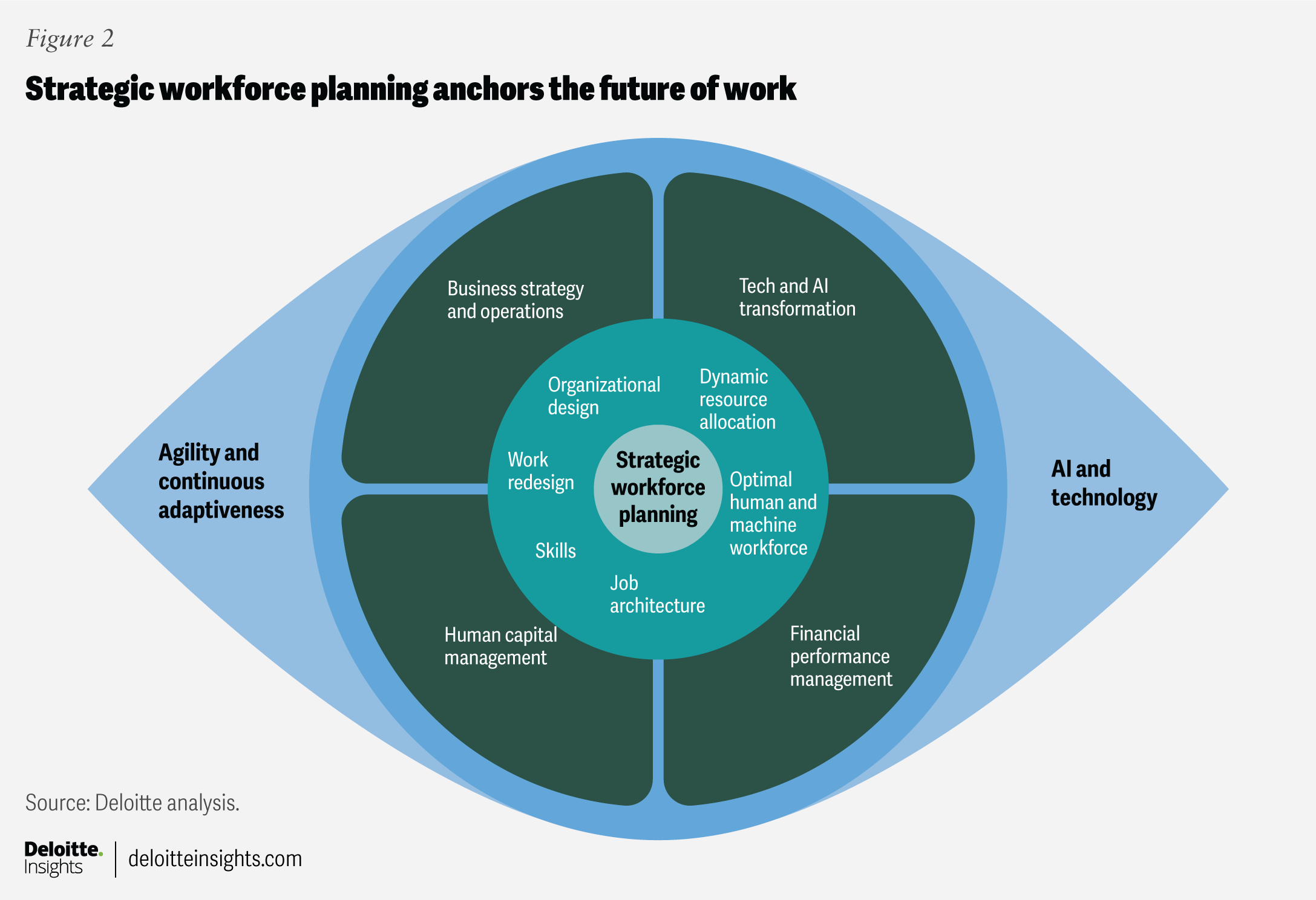

These five shifts likely require a new approach to workforce planning, one that will increasingly sit at the crossroads of finance, technology and AI transformation, human capital management, and business and strategy operations. This approach will integrate a broader set of capabilities like work redesign, fluid job architecture, dynamic resource allocation, an human and machine collaboration, effective organizational structures, and improved skill utilization.

At Hewlett Packard Enterprise, for example, strategic workforce planning is closely intertwined with the people analytics team and has recently been integrated with the organization design team. Lindsey Taylor, senior director of strategic workforce planning at HPE, says, “We needed to influence structural changes, too. The right shape of the organization, which is influenced by org design, is just as important as ensuring we have the right people in the right roles in the right time and place.” The workforce planning team is working closely with not only finance and business operations, but also the tech function to explore how some roles could be automated or augmented, all to build a more efficient and effective organization.2

No longer owned solely by human resources or finance, workforce planning is evolving into a mission-critical business capability, designed to be more fit for purpose in agile, AI-powered, human-centered organizations of the future (figure 2).

When the only aspect of the future that is known is the unknown, planning can feel like a difficult, if not impossible, task. This new, expanded approach to workforce planning will be about connecting strategy with execution and developing the ability to make dynamic decisions heavily informed by data and technology, blending humans, technology, and skills in ways that can create exponentially better outcomes for both people and businesses.

How do you plan for the future when the only thing that is truly known is that the future is unknown?

Some organizations are already adopting a reimagined approach to workforce planning. For example, one telecommunications company now calls strategic workforce planning “workforce shaping”—something it does continuously rather than as a one-time event. And health care provider Cleveland Clinic centers its workforce planning around work and job redesign in response to talent shortages in health care.3

What’s driving the transformation of workforce planning?

In order to understand why workforce planning is transforming, it helps to look at what’s driving this evolution in the first place. Many organizations are likely already feeling the effects of some of these changes.

- Increased volatility and the quest for greater agility. Leaders can no longer operate under an assumption of stability and predictability. Deloitte and Fortune’s most recent CEO survey highlights increased uncertainty as a top concern.4 This new era will likely require an always-on, sense-and-respond, continuous workforce planning approach.

- Organizing as the new competitive advantage. In today’s market, the ability to organize capabilities—which are often embedded in people—is becoming a key advantage. Unlike the industrial model, which competed on economies of scale, the new competitive advantage will likely revolve around adapting quickly and leveraging strengths. For example, Coca-Cola focuses on creating and marketing its brands, while relying on franchising its bottling operations so that partners can handle production, packaging, and delivery.5

- Human and machine convergence. AI is becoming more than just a tool for automation, often augmenting human capabilities and collaborating side by side with workers, leading to the emergence of “superworkers” who use AI to boost productivity and creativity.6 Increasingly, workers are becoming intertwined with AI—what we call convergence at Deloitte. This suggests technology could move beyond acting as an enabler, facilitator, and teammate and become woven into the very fabric of the workforce. Workforce planning will need to account for this possibility, shifting its focus from planning for the number of people or jobs to planning for tasks, skills, human capabilities like emotional intelligence and creativity, as well as capabilities embedded in AI. The convergence of human and machine also raises concerns like the potential for “cognitive debt.” Workforce planners will need to balance short-term productivity gains from AI with its potential longer-term impairment of human capabilities like creativity, memory, and independent thinking.7

- The disappearing workforce and its evolving shape. The tools and methods used in traditional workforce planning may not remain relevant amid significant workforce transformation. Fewer people are entering the job market, while a significant number of experienced workers are reaching retirement age.8 More than one-quarter of the world’s population now lives in countries where the working-age population (usually defined as ages 15 to 64) is shrinking.9 AI is also reshaping entry-level roles, making it harder for those seeking to enter the workforce for the first time. These trends are creating a workforce structure that may resemble a diamond more than a pyramid, with fewer individual contributors at the base and a bulging middle of experienced workers managing AI and workflows. The flattening of the traditional pyramid also reflects the growing trend toward less hierarchical organizations to improve agility, efficiency, and decision-making.

- The declining half-life of skills and the growing complexity of work. Unlike in the industrial era, when workers were often interchangeable, modern workforce planning is increasingly being asked to account for fluid, complex, and unpredictable work, making traditional approaches outdated. Workers are no longer fungible, with predictable skills that can be neatly mapped to jobs and swapped in and out. The pace of development in tech has been shrinking the half-life of certain skills for years; with AI potentially accelerating that trend, workforce planning is struggling to keep up. Indeed, 60% of businesses say skills gaps are holding back transformation, and 72% of CEOs say talent gaps lead to business challenges.10

- The growing need to create human outcomes, not just business outcomes. Workforce planning has traditionally focused on securing talent to meet business goals, offering benefits like cost savings, agility, and risk mitigation. But Deloitte research has shown that business and human outcomes amplify one another; when greater human outcomes are created, better business outcomes follow, and vice versa. Leading organizations are considering how workforce planning can create value for business, workers, and society holistically, with metrics that also consider human outcomes such as improved job security, reduced burnout, better well-being, and skill growth. For example, by avoiding the boom-and-bust cycle of rapid hiring and subsequent layoffs, or by reimagining worker roles instead of replacing them entirely with AI, organizations can create a greater sense of stability and employability for workers.

Five shifts to reimagine workforce planning

To help make workforce planning fit for a new, more unpredictable, AI-powered world of work— and to turn it into a true competitive advantage that helps organizations realize both business and human outcomes—we’ve identified five key shifts leaders should consider as their approach evolves. These shifts are explored in detail in the subsequent articles in this series.

From planning for the future to planning for multiple futures

Workforce planning used to rely on certain foundational assumptions about work and talent. But the heightening pace of change has rendered many of those assumptions outdated. After all, when forecasting a few months ahead becomes difficult, doing the same for a year or two becomes nearly impossible. How do you plan for the future when the only thing that is truly known is that the future is unknown?

Rather than trying to solve uncertainty, organizations can find ways to embrace it in their workforce planning. Scenario planning is a common approach to tackling such challenges, but other methods are emerging as well. Some organizations are experimenting with digital twin technologies to aid their efforts. Others are borrowing strategies from other functions entirely—for example, taking cues from finance with a “portfolio” approach to talent. Still others are experimenting with building more slack or capacity into the system to absorb future shocks; expanding beyond planning for skills to also plan for more flexible, resilient human capabilities, such as the ability to learn and apply rational judgment and critical thinking; or embracing an approach of creating as many possible or potential futures to experiment against, adjusting in real time.

From planning based on jobs to flexibly planning based on work

Jobs have long been the foundational structure of work—and, along with headcount, they’ve also been the foundation of workforce planning. But as we explore in our 2024 Deloitte Human Capital Trends article “Navigating the end of jobs,” greater agility and improved human and business outcomes can be achieved by deconstructing jobs into tasks. Work can then be reconstructed based on worker skills and abilities, as well as what AI and other technologies can do on their own or in combination with humans. Many workforce planners are now taking a task- and skills-based approach to workforce planning, looking at the best combination of resource options to perform work. These options may include external talent, automation, humans working in concert with AI, or employees in projects or roles.

However, these new approaches prioritize planning based on broader outcomes rather than focusing on granular, fractionalized tasks and skills. They emphasize giving workers expanded roles aligned with outcomes, enabling them to adapt more flexibly. Workforce planning is moving beyond the what (jobs, tasks, and skills), the who (which people and how many), the where (the location of talent), and the when (on what time horizon we need workers). It now also considers how— how work gets done—enabling planning to move beyond its traditional constraints and flexibly plan based on work and its intended outcomes.

From planning based on the visible to unlocking hidden capability and capacity

Hiring and employment decisions are often made based on visible capabilities and capacity—the known skills and availability of the workforce, both internal and external. But skills that are in demand today may not always be vital tomorrow. Organizations will likely need to discover and deploy talent flexibly to meet changing needs.

And what’s visible may only represent a portion of actual capacity. Organizations should consider the hidden capabilities they can leverage within the workforce. This includes underrepresented workers such as neurodivergent individuals, caregivers, or people without college degrees—qualified and eager workers who are often overlooked by traditional hiring practices. This could also include people with adjacent, transferable, or foundational skills who, with a bit of development, can obtain the skills and capabilities an organization needs.

Likewise, workforce planners sometimes overlook how employment models are evolving and new ways of surfacing hidden or trapped capacity. The workforce is increasingly expanding beyond only full- or part-time employees. As discussed in the book Workforce Ecosystems: Reaching Strategic Goals with People, Partners, and Technologies, organizations have other ways to get work done, including outsourcing providers, alliance partners and subcontractors, freelancers and gig workers, AI as talent, and more.11 They can also unlock capacity by moving employees to projects and work through internal talent marketplaces, or by using AI to multiply the value of talent through a blended approach of human–machine convergence.

From static, manual planning to autonomous, dynamic planning

AI has already been transforming workforce planning, enhancing its ability to predict turnover and retention rates, using real-time data to enable more accurate forecasting of demand and supply, inferring skills, activating dynamic scheduling, and simulating workforce changes in response to various disruptions.

But agentic AI may open a realm of new possibilities, ushering in a new era of more autonomous, dynamic, and iterative workforce planning. For example, AI agents can continuously monitor signals indicating workforce changes, such as potential attrition in specific skill areas, shifts in contingent labor affecting skill supply, or changes in worker capacity (whether increasing or declining). When tipping points are reached, AI can send alerts to leaders, prompting them to reassess workforce plans, including redesigning roles and work as needed. These signals can also be used to identify trends over time, helping improve predictive models of headcount, skills, and capacity.

AI agents can also suggest interventions or reallocation of resources in real time. Some agents are advanced enough to conduct triage on their own accord. For example, after a human approves a suggestion made by AI to adjust the workforce mix, an AI agent could then initiate a job posting in a recruiting system or flag potential skills gaps to trigger learning events.

From silos to synergies—both horizontal and vertical

For workforce planning to realize its full potential as a competitive advantage, breaking down silos will likely be an important factor. Workforce planning should no longer be considered the domain of finance or HR alone; leading organizations are extending workforce planning horizontally to include collaboration across multiple functional areas, including strategy and business operations, IT, and procurement.12

Leading organizations are also expanding workforce planning vertically in a way that democratizes the process.13 This creates a more collaborative and data-driven approach that empowers a broader range of leaders and workers to actively contribute to shaping the future of the organization. By leveraging data, insights, and future workforce plans, it also supports informed decision-making about how to resource work on the ground. This helps organizations gain input on decisions from the people closest to the work itself and can create greater agility and relevance.

The future of workforce planning is not one-size-fits-all

Organizations need not adopt all five shifts at once across the organization. They may choose to implement a combination of shifts for different business units based on varying levels of growth, AI adoption, and the need for agility, for example.

Beyond relying on a single process, organizations will likely need to draw on a collection of diverse capabilities to close talent gaps. Organizations no longer have just build, buy, borrow, bounce, and bot in their capability tool kit. Other “B” capabilities have also been added, such as:

- Boost (improving workforce performance and productivity)

- Bind (retaining key employees)

- Blend (combining humans and machines to boost performance)

- Break (work, organization, and role redesign)

- Bridge (moving employees to other projects, tasks, or roles to bridge the gap between employee skills and business needs)

Each of these “B” capabilities draws on a wide range of expertise from the organization, such as organization design, skills intelligence, internal talent marketplaces, capacity management, and more. With a flexible, multi-speed approach to workforce planning, these capabilities can be applied in different ways across the workforce and business, enabling tailored approaches at the right pace. Adopting a multi-speed approach also allows organizations to respond to varying needs across the enterprise.14

For example, one part of an organization may have relatively low attrition and limited growth, reducing the need for additional talent. An internal talent marketplace that fosters internal talent mobility and skills development may be the best solution in that case, allowing redeployment of resources from lower-growth to higher-growth areas of the business. In contrast, another part of the organization with significant earnings expectations and high attrition in critical roles may use capabilities such as capacity management and business capability development to plan more effectively.15

Strategic workforce planning can be your competitive edge

In an era where technological advantages can be easily replicated, human capital—rather than financial capital—has become the foundation of a successful strategy. Additionally, the advantages of economies of scale are shifting toward economies of organization, where success depends on how quickly an organization can organize capabilities to adapt to change. In this context, strategic workforce planning, reinvented, can offer organizations a lasting competitive edge.

With a reinvented approach to workforce planning, organizations can prepare for a future where their boundaries extend beyond traditional limits. Those that plan for uncertainty—anticipating future capabilities, whether human or machine—will likely be better positioned to outperform competitors in times of volatility. Success may depend on their ability to forecast, access, and coordinate the right mix of resources, both human and machine, to amplify their ability to achieve results.

Perhaps the future of workforce planning is no longer about anticipating the workforce of tomorrow, but rather, envisioning the future of the entire organization—a future in which humans and technology work together in increasingly interdependent ways, and where workforce planning becomes a living, iterative practice rather than an annual event.