Strategies for finding—and unlocking—the hidden potential in your workforce

Workforce planning leaders may be overlooking what’s available by focusing only on what’s visible. How can organizations tap into hidden pockets of worker capacity and capability?

Sue Cantrell

Kevin Moss

Russell Klosk

Chris Tomke

Zac Shaw

Michael Griffiths

The workforce is shrinking. Fewer people are entering the job market,1 while a significant number of experienced workers are reaching retirement age2 with one in six people globally over the age of 60 by 2030.3 More than one-quarter of the world’s population now lives in countries where the working-age population (usually defined as ages 15 to 64) is diminishing.4

It may be tempting to think that artificial intelligence can alleviate these talent shortages, filling gaps with efficiency-driven automation. But using AI as a form of labor arbitrage means everyone else can, too—eroding any real sources of competitive differentiation. In addition, we are operating in a human-powered economy driven by distinctly human traits like creativity, ingenuity, and empathy. Rather than automating away organizations’ unique competitive advantage, future success will likely depend on a value-based, systems-focused, human-centered approach to work and the workforce.

The challenge is that organizations typically plan for, hire, and employ workers based on visible capability—the ability to effectively perform work, which is typically measured in terms of job experience, educational credentials, or skills. They also look at visible capacity: a measure of volume regarding the net available resources an organization needs to devote to its needs.

But increasingly, what’s visible may represent only a fraction of what’s available.

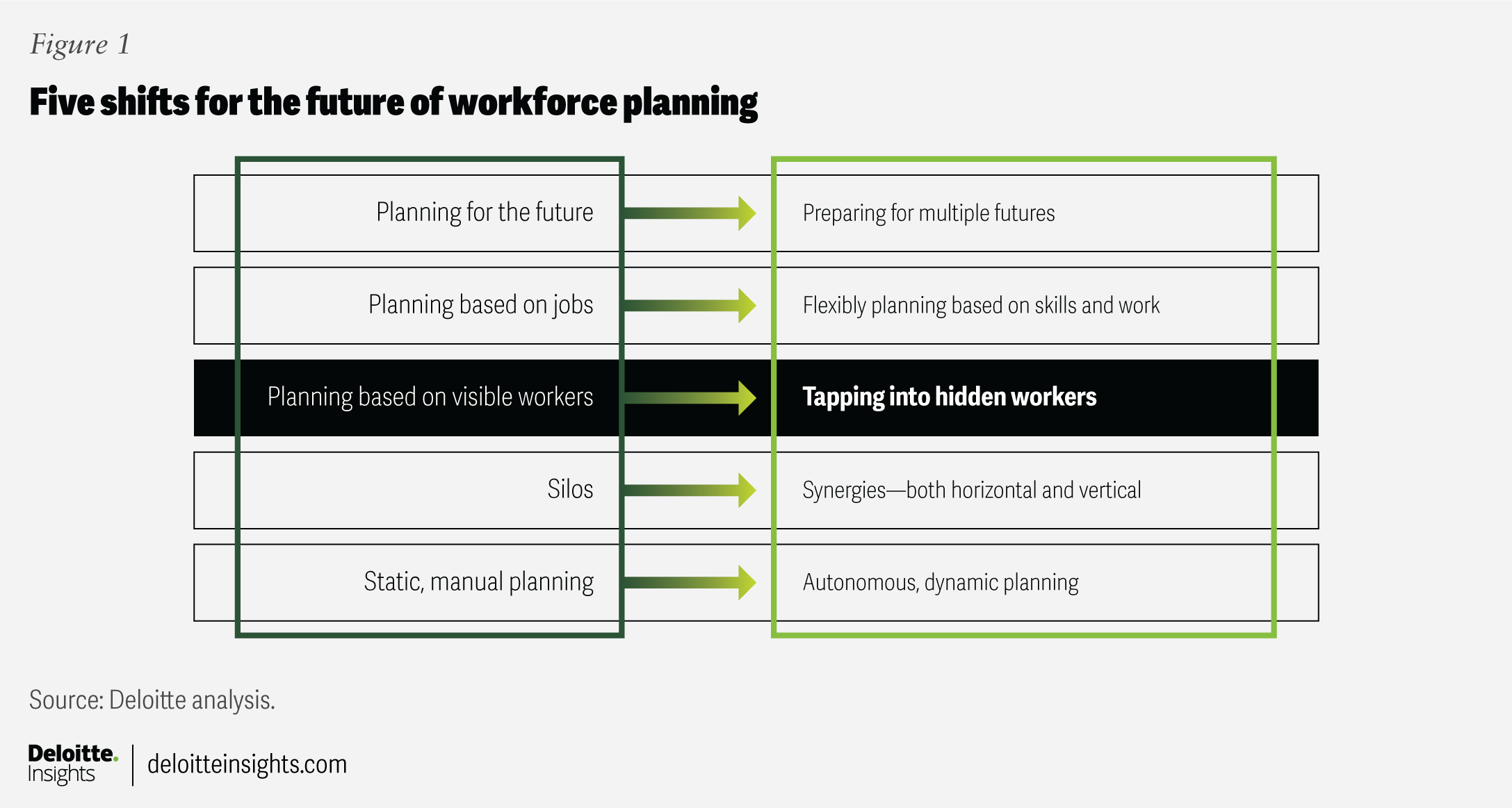

How can organizations make visible what is invisible, tapping into workers that may not be seen by organizations, and tapping into hidden pockets of worker capacity? This is one of the five shifts we explore in our series on the future of workforce planning: from planning based on visible workers to tapping into the capabilities and capacity of hidden workers (figure 1).

Uncovering this type of hidden capacity and capability can enhance an organization’s ability to plan for future needs, but it also requires taking a more holistic view of work and the workforce ecosystem. Leaders can unlock trapped capacity by using a blend of humans and smart machines to create a force multiplier of performance and productivity, by reducing busy, nonessential work to create opportunities to maximize the impact of their teams and resources, and by using AI to fluidly move workers to temporary projects. Leaders can find and acquire hidden workers and their capabilities by broadening their approach to employment models and seeking out talent that may otherwise go unnoticed, such as off-balance-sheet workers, underrepresented workers, or those with transferable skills. They can also seek out collaboration with external partners, borrowing their capabilities or even borrowing their talent through cross-company talent exchanges.

Exploring these strategies in greater detail reveals how organizations can better harness the full potential of their people, technology, processes, and partnerships.

Enhancing talent: Uncover hidden worker capacity

When it comes to capacity, organizations may be missing opportunities to consider how workers can achieve more by working with AI, reducing nonessential work, or spending time on projects outside of their core job responsibilities. Surfacing hidden capacity may mean looking beyond traditional measures of productivity to consider how talent can be redeployed, augmented, or freed from low-value tasks. The strategies that follow offer practical ways to optimize talent and utilization.

Add ‘blend’ to build, borrow, buy, and bot

Hidden workforce capacity and capability may emerge with workers who aren’t human at all. Various roles can now be filled by agentic AI, with swarms of AI agents working alongside humans as digital co-workers that can perform and execute processes like managing payroll data.5 Workday, for example, announced earlier this year its launch of an Agent System of Record, a marketplace that acts as a workforce management system for digital employees. It provides one platform to onboard new AI agents; define their roles, responsibilities, and skills; track their impact; budget and forecast their costs, support compliance; and foster continuous improvement.6

To what extent these AI agents will be counted in workforce planning tools as a separate group with the ability for leaders to directly project the impact of AI agents on headcount and skills is still to be determined, but systems like Agent System of Record will help organizations get a handle on how the landscape is evolving to provide important input into workforce plans.7 Already, Moody’s has a multi-agent system that analyzes financial filings and assesses geopolitical risks; Johnson & Johnson has AI agents collaborating with scientists on drug discovery; and eBay uses AI agents to create marketing campaigns.8 Deloitte research suggests that 26% of organizations are now actively exploring autonomous agents to perform tasks.9

The opportunities that AI creates go far beyond automation, however. The traditional workforce planning menu of build (train and develop internal talent), borrow (temporarily access capabilities through contractors or outsourcing), buy (hire talent), or bot (automate work) now has a fifth option: Blend—the ability to blend human and digital capabilities. Deloitte calls this “convergence,” where the distinctions and boundaries between technology and humans blur.10

While workforce planning may be able to account for digital labor as a separate cohort, workforce planning isn’t yet designed to account for the hidden capability of “superworkers,” in which AI dramatically enhances workers’ productivity, performance, and creativity.11 When AI is integrated with human work to become a force multiplier, how does this affect our ability to plan for the workforce? In the future, workforce planners may need to model the performance impact that AI will have on particular job families and identify where improving the work performance through human and machine convergence pays off most.

We anticipate this to be a growing area of importance to strategic workforce planning, beyond considering AI as a digital worker. According to a study done by Orgvue, 55% of surveyed leaders say that making people redundant following the implementation of AI was the wrong decision.12 Already, we are seeing organizations change their tune about using AI to replace human workers. A year after claiming that its AI chatbot could do the work of 700 representatives, financial tech company Klarna is turning back to people to handle more of its customer service work. According to Klarna spokesperson Clare Nordstrom in reporting on Yahoo Finance, “While Klarna pioneered the use of AI in customer service with groundbreaking results, this strategy will now evolve to the next level. AI gives us speed. Talent gives us empathy. Together, we can deliver service that’s fast when it should be, and emphatic and personal when it needs to be.”13 The shift highlights the importance of using AI as a colleague and force multiplier of people, rather than a replacement.

Boost capacity by getting rid of nonessential work

Beyond considering how to build, buy, borrow, bot, or blend, workforce planners can consider another “B”: Boost—improving workforce and productivity. Focusing workers on what matters most can help—something we talk about in our 2025 Global Human Capital Trend, “When work gets in the way of work: Reclaiming organizational capacity.”

According to our Trends research, survey respondents say 41% of their time every day is spent on work that doesn’t contribute to the value their organization creates. And a third of respondents to a survey conducted by software firm Visier say that they prioritize work that is most visible—regardless of whether that work is actually valuable to the business.14 By reclaiming that time spent on nonessential work, organizations can multiply the capacity of their talent.

For example, the workforce planning team at nonprofit health system Providence Health deconstructed its nursing role and discovered that while the job included many “top of license” tasks (those that utilized nurses’ high-level medical skills), it also included many tasks that others without specialized training could perform. Highly trained nurses were spending a significant amount of time on basic tasks like taking patient temperatures and recording information on hospital charts. Not only was this costly, but it also affected the nurses’ engagement and job satisfaction. To solve this problem, Providence created a new patient attendant role that delegated these tasks to student nurse assistants, not only freeing up the time of the most qualified nurses but also creating a pipeline of future skilled nurses in the process.15 This boosted the performance and productivity of the nurses, helping them address a severe staff shortage.

Unlock capacity with talent-sharing

Internal talent marketplaces are often an underrecognized lever for surfacing hidden or trapped capacity. These AI-powered digital platforms within an organization match workers to internal opportunities like short-term projects, gigs, full-time roles, and stretch assignments, in addition to mentoring or learning pathways based on their skills, interests, experiences, and career goals. Unilever, for example, unlocked 650,000 hours of workforce capacity with a 41% overall productivity boost,16 and Mastercard used its talent marketplace to unlock US$21 million in productivity in its first year.17

Another source of hidden workers is talent that can be temporarily borrowed from other organizations. During the COVID-19 pandemic, a number of organizations developed cross-industry talent exchanges, temporarily moving employees without work due to the crisis (those working in airlines or hospitality, for example) to organizations that had an excess of work (health, logistics, some retail stores).

In China, restaurant and catering companies loaned out-of-work employees to Hema, Alibaba’s retail grocery chain known for its fast grocery food delivery, which was experiencing a spike in demand. More than 3,000 employees from more than 40 companies in different sectors joined Hema’s employee-sharing plan during the pandemic.18

Though these examples were undertaken during extraordinary circumstances and have largely disappeared today, cross-company talent exchanges—done more broadly and consistently—offer a potential future direction for strategic workforce planners.

Talent acquisition and expansion: Broadening the talent lens

Organizations may overlook workers with unrelated job experience or qualifications, even though career changes and shifts in employment models are becoming increasingly common. Entire swaths of workers may have experiences and abilities that equip them for other roles, even if that potential does not show up in a skills inventory or talent marketplace. How can organizations broaden their talent lens, understanding that the right talent may not always come through traditional channels?

Consider all employment models

How do you define the workforce? Traditionally, organizations have defined it as full- or part-time employees. But organizations have other ways to get work done, including outsourcing providers, alliance partners or subcontractors, freelancers and gig workers, AI as talent, and more.19 Workforce planning sometimes overlooks the broad array of resources to apply to work. While 84% of executives in a Deloitte Global Human Capital Trends survey say that effectively managing this blended workforce ecosystem is important to the organization’s success, only 16% say they are ready to do so.20

Consider gig workers, which some estimates suggest now represent as much as 12% of the global workforce.21 Even many full-time employees report earning supplemental income, with 62% indicating they have a side hustle in addition to their main occupation.22 Organizations are already leveraging extended workers, with recent research showing that approximately 48% of an average US corporation’s workers are engaged in a contract, contingent, or other nonemployee relationship.23 But these workers are often excluded from workforce planning discussions. Not only does this deprive organizations of a comprehensive picture of their workforce needs (e.g., if certain functions are entirely outsourced), it can also limit an organization’s planning options, putting constraints on their ability to allocate the right workers against the right roles at the right times.24

Some organizations like Unilever are developing models to plan for and source contingent workers more accurately by utilizing them on a longer-term basis. The company’s U-worker program enables external workers to have a guaranteed minimum retainer along with a core set of benefits when they contract with Unilever for a series of short-term projects. Not only does this provide a greater sense of stability for workers, but for Unilever, it has also helped retain talent that may face barriers to staying in the labor market among a shrinking talent pool (e.g., parents and caregivers).25 Platforms like this enable greater visibility into these types of workers and the capabilities they can deliver, helping expand workforce planning efforts to account for a broader workforce beyond employees. And because a program like Unilever’s draws on a vetted pool of external workers who repeatedly engage in various projects based on a minimum number of hours to qualify for the benefits, it can make it easier to account for this type of external talent in workforce planning.

New work models are also developing in the freelance space. For example, some emerging platforms are enabling organizations to hire whole teams of workers who have already developed the camaraderie, ways of working, and synergies with one another as they rotate from organization to organization, taking on projects as a team. An “elastic” team of 23 assembled by the platform Distributed, for example, was contracted for more than 18 months to do specialized technical and coding work at BP Launchpad to help it meet its mission of scaling companies seeking to become carbon neutral by 2050.26

Similarly, workforce planners could consider planning for work to be done by external teams and groups, not just individuals.

Leverage adjacent and foundational skills

The extended, external workforce offers a fairly straight line to accessing capability—a certain group has certain skills that fulfill certain needs. The challenge, as noted, is in identifying the workers. But there’s also an inverse path available, starting with the workers first and then identifying the need they can fulfill. Organizations have much to gain from considering entire talent segments in new ways. Adjacent skills gained in one role may be applicable in another seemingly disconnected one.

Consider Walmart, which found itself facing a looming wave of retirement among skilled professionals in manufacturing and transportation. In 2022, the organization launched a pilot program to help supply chain employees earn a commercial driver’s license and join the company’s private fleet. The 12-week program proved so effective that Walmart has since expanded it for other in-demand roles, such as certified technicians. By identifying groups with high potential and adjacent skills for these roles, the company not only addressed business needs without large-scale external hiring but provided its workforce with upward economic mobility.27

After integrating AI into its call centers, Salesforce realized it had more workers than it needed. Instead of layoffs, the organization identified transferable skills and redeployed two-thirds of employees into roles like customer success, sales support, and AI monitoring.28 Siemens, after transforming manufacturing with AI, identified adjacent skills for displaced workers, reskilling them and moving them into data analytics, robotics, maintenance, and software engineering roles.29

Look for hidden talent to borrow or acquire

Borrowing talent is another strategy for unlocking hidden capability and capacity. Beyond tapping into contingent workers, organizations can borrow talent by creating strategic alliances or partnerships that can enable them to tap into talent from other organizations. For example, two pharmaceutical companies might collaborate to bring a new therapy to market, with one bringing development expertise and the other leveraging specific clinical knowledge. Dell developed a corporate venturing arm to invest in early-stage startups, giving it a way to access or eventually acquire talent and intellectual property.30

It can be hard to spot and evaluate talent in potential alliances, mergers, or acquisitions, however. But AI is helping organizations make this talent more visible. One firm, for example, continuously monitors the workforce of dozens of acquisition targets by sourcing public data ranging from patent findings to citations and social media posts. These sources provide important data about employee engagement, corporate culture, and the workforce’s innovation capabilities. The firm’s algorithm uses these data sources to suggest additional companies to consider for acquisition or as comparisons of a peer group.31

Another multinational organization used a combination of patent data and social network analysis to better understand the talent of a company it was merging with six months prior to the merger. By analyzing patent data, the team identified key inventors, social influencers, and critical knowledge holders, which helped inform leadership selection, retention contracts, and team integration planning post-acquisition. This outside-in strategic workforce planning method offers broad strategic applications beyond mergers and acquisitions. External data sets, such as job ads, regulatory filings, and employee profiles, can reveal competitor strategies, guide site selection, and benchmark skill availability and workforce costs across regions.32

Tap into underrepresented workers

Hiring processes may overlook what Joseph Fuller, a Harvard Business School Future of Work professor, calls “hidden workers.”33 These include caregivers, the formerly incarcerated, veterans, people without college degrees, people with disabilities, and more. These populations aren’t always considered by workforce planners as potential sources of talent to fill gaps. Yet Fuller’s research suggests that in the United States alone, there are more than 27 million hidden workers.34 Tapping into these populations can help organizations fill jobs, while workers and society can also benefit from increased employment opportunities.

Some organizations have committed to combatting the skills gap through impact sourcing, where they work with nonprofit organizations and charities to create employment opportunities for workers who aren’t fully represented or accounted for in traditional labor force statistics—for example, neurodivergent individuals, people with long-term health issues, and those without traditional degrees or qualifications.35

SAP’s “Autism at Work” program, launched in 2013, reports a 90% retention rate among employees on the autism spectrum by providing tailored support systems,36 and JPMorgan Chase has a program that matches neurodiverse candidates to suitable roles, resulting in decreased error rates and improved team morale.37

Unlocking hidden capability often involves rethinking job prerequisites. Verizon, for example, as part of its shift toward skills-based hiring, has opened doors to talent without four-year degrees, individuals that previously may have been overlooked.38 The company also offers a free “Skill Forward” program that provides individuals with free certification courses to upskill into various in-demand roles, with the goal of preparing 500,000 individuals for such jobs by 2030.39

Practices for unlocking hidden potential

Recognizing the untapped potential in the workforce is just the first step. Leaders will likely need to rethink traditional workforce planning approaches to help uncover and activate this hidden talent. Leaders can consider the following practices to maximize the capabilities and capacity of their teams.

- Determine what work should be performed by what workers. A prerequisite to planning for the full workforce ecosystem is establishing what an organization is willing to have done by different worker types (employees, contingent or freelance workers, AI agents, etc.). An organization’s answers will depend on its context—what works for a consumer retail company may not work for a telecommunications company—and will help inform how it weights its planning model.

- Maintain accurate, robust data on the extended workforce. To consider the entire workforce ecosystem in workforce planning, planners will need to integrate data sources and processes to get a view of their entire workforce. Many organizations struggle to maintain clean, reliable data on their own employees. Gaining that level of accuracy on workers outside the company’s walls—including their skills, experiences, and strengths—presents an even trickier proposition. Since Procurement usually manages contractors and individual managers often hire temporary workers or consultants directly, close collaboration with these leaders and functions will likely be necessary to collect robust data on external workers to inform decision-making.

- Beware of increasing amounts of disinformation about workers. Even as organizations strive to build accurate workforce data, with the rise of AI hallucinations and AI-generated fake content, trustworthy data on workers is becoming increasingly difficult to get and vet. Strategic workforce planners will likely need to create new practices and processes aimed at disinformation security to ensure their plans are accurate and that data collected on workers isn’t falsely generated by AI. In general, smaller, targeted, high-quality data sets are superior to larger, diffuse data of unknown quality.

- Use skills to break down invisible barriers. A clear and accurate skills taxonomy can identify not just an organization’s needs but new capacity to solve them. Traditional experience requirements, for example, may apply to only a select group of workers, while skills can be found in a wide range of individuals from all manner of backgrounds. Mapping skills back to different worker types can help optimize an organization’s resource allocation.

- Work with the information technology department to plan for the new blend of human and digital workers. When there is a new blend of AI and humans performing the work, IT and human resources departments will have to work more closely to plan for future workforce needs. Jensen Huang, CEO of Nvidia, puts it this way: “In a lot of ways, the IT department of every company is going to be the HR department of AI agents in the future.”40

- Avoid anthropomorphizing AI agents. In recent years, many have talked about treating AI as a kind of digital worker, anthropomorphizing it and applying the same workforce management practices to AI as we do to employees. While this may make sense for AI as automation, where a machine is working on its own, it doesn’t make as much sense in a world where workers are increasingly collaborating with AI, often in ways that make it hard to distinguish where the AI work begins and the human work ends. Anthropomorphizing AI is a mindset that assumes work happens sequentially, in silos, and independently. Treating AI as distinct actors from humans doesn’t get at the heart of helping workers collaborate effectively with AI—which is where real performance improvements can be had.

As demographic changes and technological advances reshape the labor market, relying on traditional workforce planning approaches may be limiting organizations. Instead, organizations should look beyond what’s immediately visible—like job experience or traditional employment models—and uncover the hidden potential in their workforce.

This means broadening the way we think about talent. Workers with transferable skills or unconventional backgrounds could bring fresh perspectives to the table. Collaboration across teams and even external partnerships can open up new possibilities. And AI can play a role too—not as a way to replace people, but as a tool to multiply the value of what they do—helping them work smarter, eliminating busywork, and focusing on what really matters.

By tapping into hidden talent and thinking creatively about how people and technology work together, organizations can turn today’s workforce planning challenges into tomorrow’s opportunities.