From jobs to skills to outcomes: Rethinking how work gets done

Workforce planning is moving toward a future where outcomes define the work. How can organizations embrace task- and skills-based planning now, while preparing for what comes next?

Sue Cantrell

Kevin Moss

Russell Klosk

Chris Tomke

Zac Shaw

Michael Griffiths

Jobs have long been the foundational structure of work—and, along with headcount, they’ve also been the foundation of workforce planning. But in an environment driven by digital transformation and automation, existing roles can disappear, and new jobs can emerge with little precedent.1

An analysis of 15 million job postings between 2016 and 2021 found that nearly three-quarters of jobs changed more from 2019 through 2021 than in the previous three-year period.2 Some jobs are being added while others are displaced due to artificial intelligence, and Deloitte’s Human Capital Trends research found that jobs increasingly don’t reflect the work actually being done—71% of surveyed workers already perform some work outside of the scope of their job descriptions, and only 24% report they do the same work as others in their organization with the same exact job title and level.3 Only 19% of business executives and 23% of workers say work is best structured through jobs.4

Given the speed at which jobs are changing, workforce planning based entirely on job or headcount may no longer offer organizations the agility they need. Workforce planners are increasingly using another unit of analysis to plan for the future: tasks to reflect work, and skills to reflect people—replacing jobs and employees, respectively.

But making skills or tasks the primary units of analysis in workforce planning raises questions even as it offers solutions for today’s needs. As routine work is increasingly automated and human work grows more complex, with human capabilities at a premium, how long can a task- and skills-based approach to work remain relevant? What alternatives should workforce planning leaders already be thinking about?

To keep pace, organizations may eventually need to move beyond simply shifting from jobs to skills or tasks. The future of workforce planning lies in integrating skills, technology, and work design into a more fluid system—one where work and roles aren’t defined by static descriptions but by the outcomes they’re meant to achieve and the problems they exist to solve.

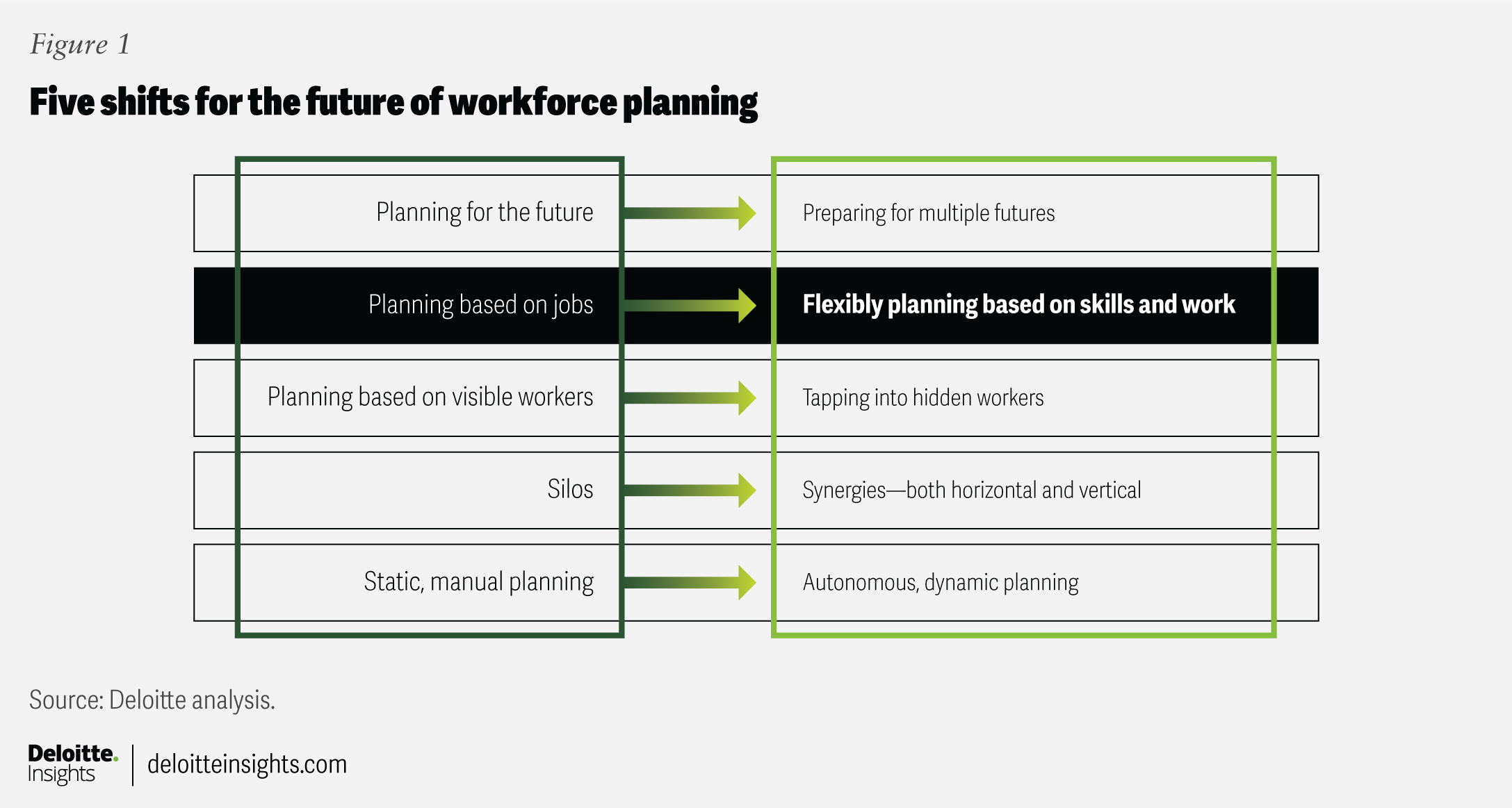

This article, the second in our series on the future of workforce planning, explores the shift from job-based planning based to more flexible, work-based approaches (figure 1).

Jobs once defined work. Tasks and skills are redefining it.

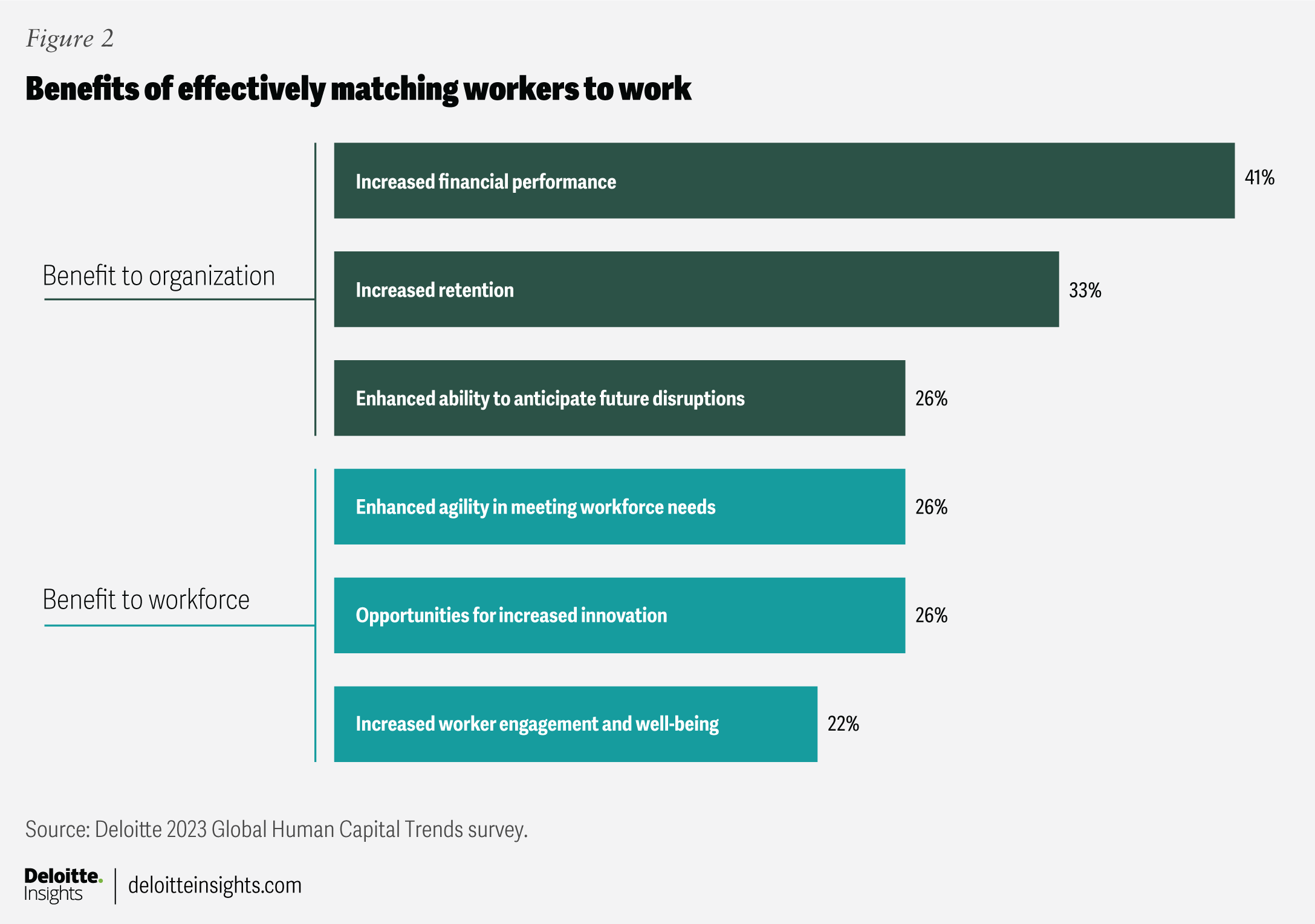

Task- and skills-based approaches to workforce planning can grant organizations an additional level of detail to refine their approach and home in on their critical needs. More organizations are recognizing the value of this approach. Deloitte research reveals that 93% of survey respondents believe that moving away from the job construct is important or very important to their organizations’ success. Respondents cited a number of organizational and workforce benefits from more effectively matching workers to work (figure 2).5

In fact, many organizations are already finding themselves in this new terrain—shifting from jobs as the anchor to tasks and skills as the building blocks. The challenge is now understanding what each lens offers, how they can work together, and when alternative approaches should be considered.

Tasks first: Breaking down jobs for better agility

Nearly all approaches to workforce planning start with understanding the work needed to create outcomes before moving on to the skills needed to perform it. What varies is how best to understand that work.

As we discuss in Deloitte’s 2023 Human Capital Trend “Navigating the end of jobs,” greater agility and improved human and business outcomes can be achieved by deconstructing jobs into tasks, and then reconstructing work based on worker skills and abilities. Many planners are now combining tasks and skills to identify the best resource options, whether that means external talent, automation, AI-human collaboration, or employees in projects or roles.

It starts with tasks—what some call “work-task planning,” an approach to redesigning workforce planning around work instead of people, and capabilities instead of capacities.6 For instance, Unilever identified more than 80,000 tasks it expects to be performed by a combination of full-time employees, gig workers, contractors, and flexible talent over the next five years.7

Yet according to the Institute for Corporate Productivity, only 22% of organizations are effective at breaking down jobs into tasks.8 Technology is stepping in, with new tools emerging to build dynamic task libraries—creating taxonomies of work activities and providing role-level insights into tasks and workloads.

For example, WPP is using the Reejig platform to look at the jobs in its organizations and create a job task library that updates itself in real time. Revelio Labs has built an activities taxonomy derived from job postings and résumés.9 A whole host of technologies, including Deloitte’s Workforce Analyzer tool, enable organizations to look at individual roles and see what tasks and workloads exist.

Interest in task-based workforce planning is growing, driven by the pace of change, automation, gig work, remote models, and advances in natural-language processing to analyze tasks. Disaggregating jobs into tasks makes it easier to rebundle work—some done remotely, some automated, some by external talent, and some even by customers (think self-service kiosk checkout in retail stores). Because tasks are easier to change than jobs or people, organizations gain flexibility to reconfigure work and close talent gaps with greater speed and agility.

Planning work through the lens of skills

Closely aligned to task-based planning is skills-based planning, often done together. After understanding the work, organizations need to determine the skills needed to perform it. When skills deliver on tasks, the two combine to deliver business outcomes. Skills-based planning enables more precise talent gap analysis and allows workers to be redeployed as needs change based on their skills, giving organizations greater agility.

As skills-based approaches become a cornerstone of workforce planning, a unified understanding of skills across the organization becomes important.

For example, to activate a skills-based workforce planning process, Verizon revised its job taxonomy, analyzing 140,000 employees across 11,000 job codes and consolidating them into 10 job families across 2,400 job codes aligned to individual employees. This shift clarified the specific skills needed for each role and created clearer connections across the talent ecosystem—from hiring and deployment to internal development. The company has since doubled down on its skills-first approach to hiring, enabling three-year talent forecasting plans that give human resources visibility into the skills the company has, those it needs, and the best way to source them.10

Technology is playing an increasingly essential role given the inherent complexities of skills-based workforce planning. AI can map employee skills, pinpoint gaps, and recommend learning and development strategies. AI-driven platforms can build and update skills taxonomies; create skill inventories in real time; and support applications such as workforce planning, resource management, and project staffing.

By shifting focus from jobs to skills, organizations are better able to anticipate capability needs, personalize learning, and improve retention. Johnson & Johnson, for example, uses AI to infer skills, enabling leaders to analyze existing capabilities, identify areas for skill-building, and increase retention by helping employees find new career paths within the company.11

Some organizations are going further, using technology not only to identify skills, but also to embed them into core work processes. IBM uses AI, analytics, and machine learning to infer employees’ skills and proficiency levels from their digital footprint, creating a reliable baseline to track and predict skill supply. This data informs workforce planning, personalized career coaching, and targeted learning recommendations, while also helping guide compensation decisions. The approach has contributed to measurable outcomes, including improved sales revenue and higher employee engagement.12

Deconstructing jobs, reconstructing work and roles

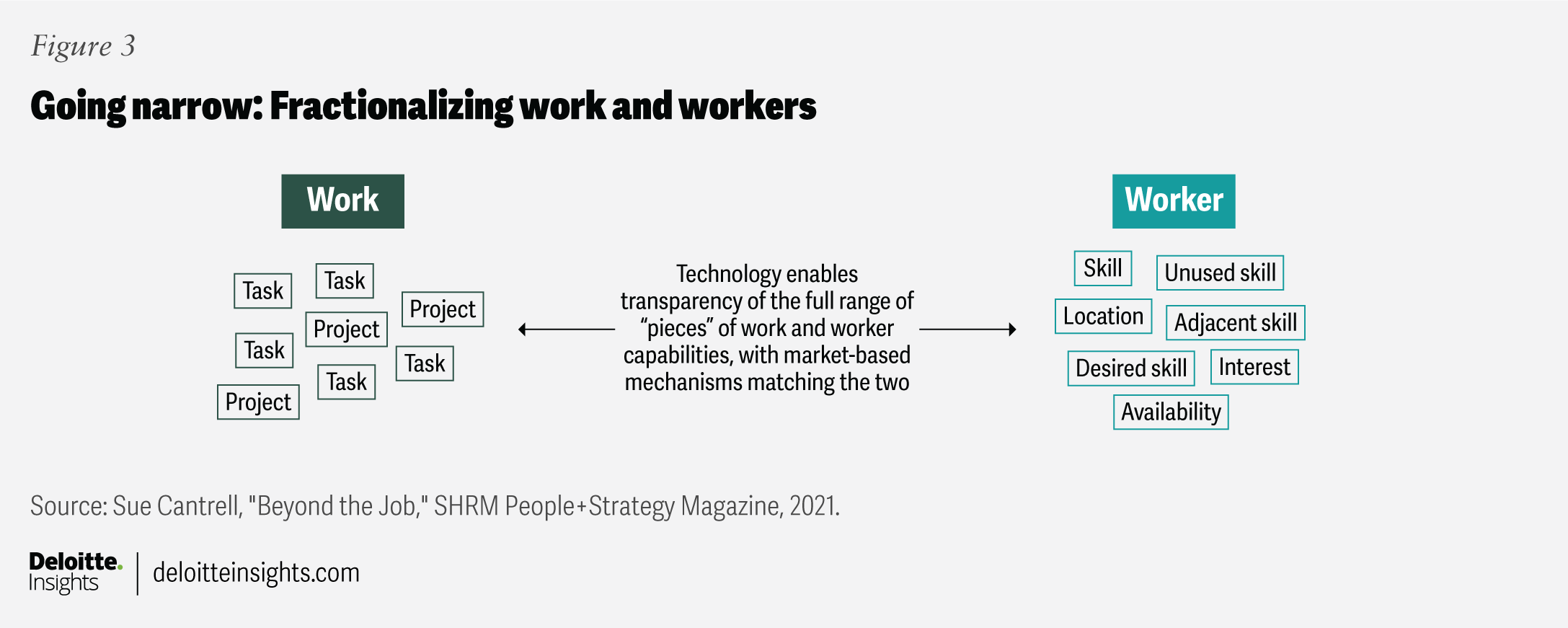

Breaking work apart from rigid job structures into smaller pieces—what we call fractionalized work—allows people to move fluidly toward where they’re most needed, whether that’s a project, assignment, or cross-functional initiative (figure 3). Likewise, looking beyond job titles to tasks or the full spectrum of an individual’s skills, experiences, and interests makes it possible to see employees as whole people rather than fixed roles.

When it comes to workforce planning, leading organizations are using analysis into skills and tasks to give organizations new ways to break work and workers into their core components and match them. But breaking work down is only part of the story. The real opportunity may lie in how organizations put those insights back together—redesigning roles and rethinking how work is performed to create more agile, effective solutions than traditional supply-and-demand forecasting alone can provide.

Health care provider Cleveland Clinic recognized that a traditional workforce planning approach wouldn’t solve for a massive shortage in health care workers—including 1.6 million unfilled jobs, and an average job posting only getting two responses. Instead, the workforce planning team turned to role design, breaking down tasks and asking whether each needed to be done, and whether they could be automated, performed remotely, reassigned, or rescheduled.

For medical assistants, this analysis led to shifting most tasks (37 of 40) to lower credentialed or non-clinical staff and automating or augmenting other tasks with technology. The organization’s approach effectively turned workforce planning into the “action arm” of HR, supported by cross-functional teams and internal partners like talent acquisition and total rewards. As a result of its changes to roles like the medical assistant, Cleveland Clinic created the capacity equivalent of 430 full-time employees and generated more than $2 million in cost avoidance,13 and boosted employee engagement by enabling staff to spend more time on patient care instead of paperwork.14

Adding technology to the tasks and skills equation

Technology platforms have often helped organizations with skills, or with tasks, but not always both. While some organizations focus more on one or the other, it’s ultimately the combination of both tasks and skills—in service of outcomes—that will help organizations better plan for a future in which work and workers are in continuous flux. And emerging advances in technology such as AI agents are changing the equation, adding and integrating directories of AI agents to existing skills and task taxonomies.

Technology platform Gloat, for example, recently revealed its new work orchestration platform that integrates skills, work, and technology as a performer of work. The platform also integrates planning, execution, and development. In addition to helping workers develop new skills and assisting leaders in their efforts to model and plan where AI can make the biggest difference, its Mosaic solution helps managers and workers dynamically decide how to best resource work—whether that be human or machine. Powering it all is a multiontology workforce graph, which creates a common language connecting humans, AI, technology, and work.

Esty Yehuda, vice president of product at Gloat, explains, “In the AI era, skills are the currency of talent, and tasks are the currency of work. This requires a different approach for workforce planning and development. To quickly assemble and reassemble capabilities, people need visibility into skills, work and technology to orchestrate them effectively.” Mastercard, along with other companies, has entered a design partnership with Gloat on Mosaic. Users will be able to enter the type of work they want to do or an outcome or objective they want to achieve, and the technology will surface relevant workstreams, people who have the skills to execute those workstreams, and technologies (including software, gen AI, and AI agents) that can either work with these people or perform the work autonomously—helping design and redesign work in real time.15

Mastercard, Seagate, and Standard Chartered are exploring such platforms, with users able to enter the type of work they want to do or an outcome or objective they want to achieve. The technology will surface relevant workstreams, people who have the skills to execute those workstreams, and technologies (such as AI assistants or agents) that can either work with these people or perform the work autonomously—helping design and redesign work in real time.

In another example of technology converging with tasks and skills, one internet retailer has merged its information technology and HR departments in recognition that both AI and people can perform work, as leadership believes that the roles of both IT and HR share the same objective: to help distribute work to where it needs to be done.16

Emerging alternatives to task- and skills-based planning

Work and role redesign through workforce planning is one way organizations can use tasks and skills to reconfigure roles in more agile ways. But even using skills and tasks rather than jobs as the unit of analysis has limits.

The declining half-life of skills, for example, may make the shift to skills-based planning more difficult. Work that differentiates an organization in the marketplace—and the tasks that underlie it—is more likely to change with customers’ requirements. For some jobs, work may be so interconnected that it’s almost impossible to disaggregate into tasks. Strategic and knowledge work may be especially difficult to break down, as those roles are not task-based. Instead, they draw more on human capabilities like emotional intelligence, critical thinking, and creativity that are harder to observe and quantify. And for many organizations, the work required in strategic roles often bleeds into other functions. According to Deloitte’s skills-based organization research, 81% of surveyed business executives say their work is increasingly performed across functional boundaries.17

Disaggregating the job into component tasks, determining which tasks can be performed more optimally by smart machines or alternative talent outside of the organization’s walls, and then reassembling the remaining tasks with new ones to create a newly reconfigured job is a top-down, engineering-like approach still rooted in a mechanistic mindset that doesn’t give workers much choice or agency. Often, the focus is on chasing efficiency and cost reduction instead of opening up new opportunities to unlock growth and value. And the world is simply changing too fast to go through this process again and again each time a new technology emerges, markets shift, or new opportunities present themselves.

These challenges point to the growing need for emerging alternatives to task- and skills-based workforce planning.

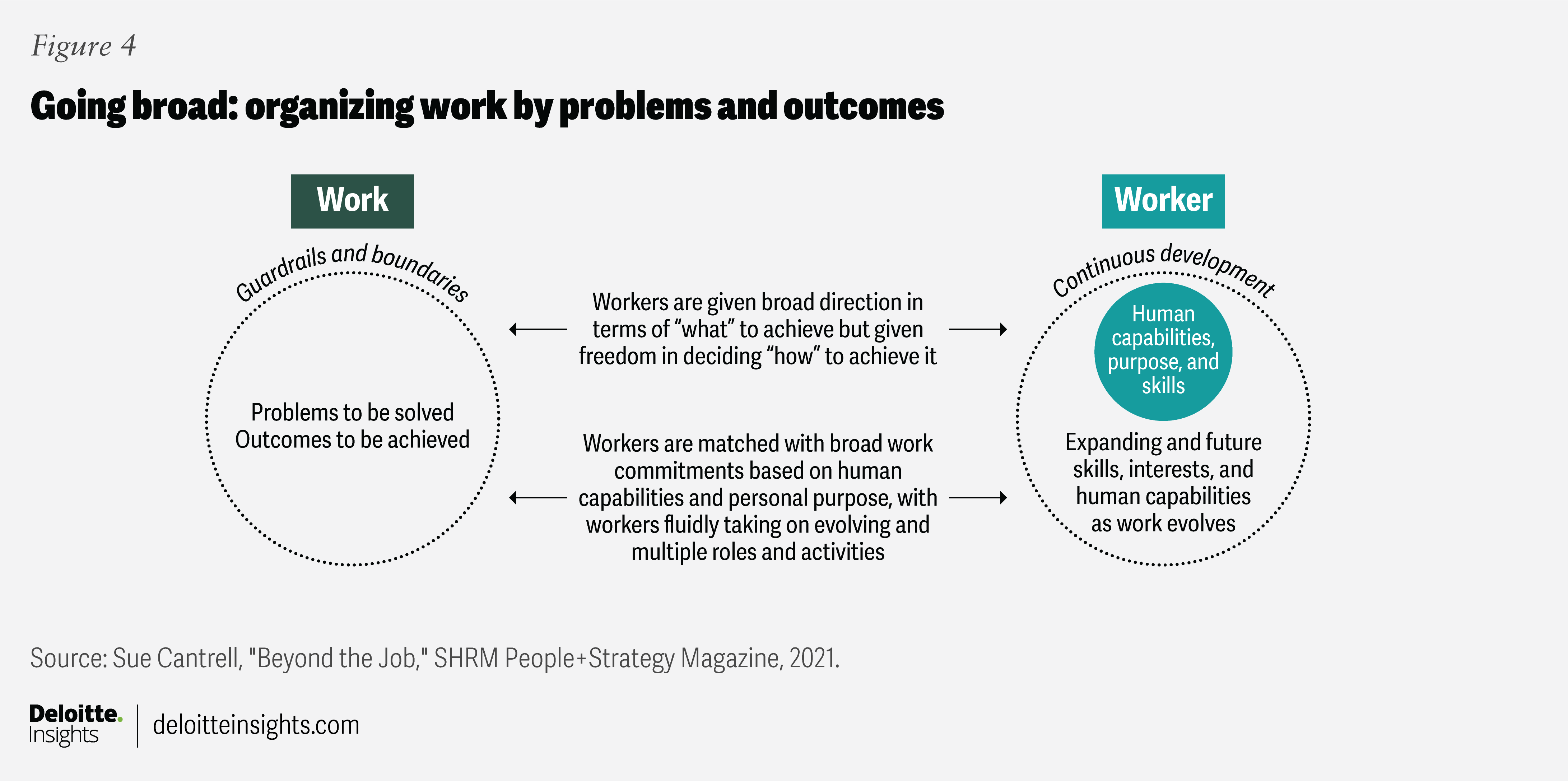

Instead of fractionalizing work into its component tasks, organizations could move in the opposite direction, broadening people’s roles so they are structured based on achieving outcomes, solving problems, or creating new sources of value (figure 4). Doing so can essentially provide guardrails for workers in terms of the broad “what” of work—but give them the freedom and autonomy to choose the “how.”18 Our research reveals that organizations that take this approach are nearly twice as likely to place talent effectively and retain high performers, as well as have a reputation as a great place to grow and develop.19

Each approach—disaggregating or fractionalizing work into tasks and people into skills, or broadening work with guardrails and focusing more on human capabilities—has advantages and potential risks (figure 5). What might be right for one organization may not be right for another, and certain types of work and roles may be better served by one approach over another.

Figure 5

Risks and benefits of fractionalized and broadened approaches to workforce planning

${optionalText}

For workforce planners, planning based on a broader problems-and-outcomes construct may be too ambiguous and difficult to use as a unit of analysis. However, some thought leaders, researchers, and organizations are starting to explore similar, outcome-based alternatives for workforce planning that aren’t based on job, task, or skill.

Michael Grove, founder and chief organizer at HumanCentric Labs, is working with organizations to use technology he developed that uses “services” as the unit of analysis for organization design, planning, and work. A service is defined as a piece of work that has a supplier, customer, and measurable value exchange. According to Grove, “We replace traditional job structures with a service-based model where human and AI resources work together to solve problems. The focus is on maximizing value while minimizing costs, using a supply-demand market-based org design. The result is less hierarchy, shifting management layers into customer value chains. The service model enables the rapid improvements in talent and AI integration.” The value of a service is determined by attributes of value as perceived by the customer receiving the service. Value less cost represents the margin contribution of each service and sum of services.20

Semiconductor manufacturer GlobalFoundries also focuses on outcomes, but takes a process-based approach to doing so. When the company set a goal to transform from a commodity contract wafer manufacturer to focus on making specialized chips for device manufacturers in high-growth markets like 5G and the Internet of Things, it didn’t start planning efforts by thinking about skills or tasks. Instead, the company started with outcomes it wanted to achieve in eight key end-to-end processes: idea to product, hire to retire, order to cash, demand to deliver, source to pay, market to contract, make to order, and record to report. Brad Clay, who served as the chief information officer during the transformation, stated, “We wanted to understand and define how our processes could be interconnected and work end to end. We had to break down the silos that naturally occur between finance, planning, and supply chain, for example. We did not start with an organizational construct. We started with a process construct.” Each process was led by executive-level leaders in newly created global process owner roles, with transformation targets starting at 50%. The shift to a focus on the company’s end goals resulted in improved outcomes such as increased productivity and faster decision-making.21

Another example of alternative workforce planning comes from a financial services provider, which realized that a traditional approach (supply analysis, demand and gap analysis, etc.) was not suitable for more complex, strategic jobs that could not be translated into a skills gap analysis. For these types of roles, the organization used an alternative approach to traditional workforce planning it called the “network approach,” which focuses on a specific role’s ecosystem, community, role, reputation, population, and individual workers. The company is considering expanding this approach with an external network view that considers the global ecosystem, country ecosystem, industry ecosystem, and organizational ecosystem for each role.22

Putting new workforce planning approaches into practice

Understanding the benefits and risks of task- and skills-based workforce planning, and how emerging alternatives can help address their limitations, is a good starting point for reimagining workforce planning. Deciding how to put these approaches into practice, however—choosing the right entry points, sequencing efforts, and tailoring solutions to the organization’s context—can be challenging. The following considerations can help chart a practical path forward.

- Start with what’s critical. Creating an exhaustive skills inventory for an organization’s workforce is a monumentally complicated task. Start with the skills that are mission-critical today and in the near future, rather than “boiling the ocean” by including every single skill. Research shows that in a typical organization, 5% of roles carry 95% of the business impact.23 Same with tasks; task-based planning is likely to have more impact in the strategic positions and jobs that differentiate an organization’s success.

- Avoid over indexing on terminology. Don’t worry so much over whether something is a skill, human capability, knowledge, competency, or some other category, or whether something is a task, project, or activity. The same applies to job, position, and role. As long as you understand what the unit of measurement represents in your organization, worrying about precise words may be more trouble than it’s worth.

- Meet the business where it is. Processes, tools, and people will look different for different functions. As a first step, ensure skills-based conversations are proceeding consistently within functions before worrying about standardizing across the business.

- When redesigning work, take a data-driven approach, but rely on people for the creative reinvention. While data can inform how to best allocate capabilities, whether they come from people or technology, it is ultimately humans who should decide how to do so. Those humans will need to ensure their decision-making accounts for bias, and that a variety of perspectives are included in the decision-making, from workers to HR, finance, and technology professionals.

- Recognize the power of starting with low-tech tools and maturating as you go. With strong Excel skills, you can uncover meaningful insights and identify where you want to know more for the future as you progress. Also, be innovative in your gap-closure solutions. Organizations can identify skills gaps and future capabilities needed for the business, for example, with structured internal interviews. However, when trying to more accurately account for the work of thousands of employees across different roles, performing different tasks, and with different skills, the right technology will be important.

- Don’t plan on a one-size-fits-all approach. Certain roles—in particular, highly strategic and knowledge-based roles—don’t lend themselves well to a task-based workforce planning approach. And as we will explore in an upcoming report on getting to outcomes with skills, there are various paths to value based on intended outcomes. An organization need not implement every skills-based technique; only the ones most relevant to the various strategic outcomes (e.g., increased agility, growth and innovation, cost optimization, etc.)

No single approach to workforce planning will work for every organization, and the path forward is unlikely to be linear. What may matter most is starting where the impact is greatest, staying flexible, and positioning outcomes as the guide. In doing so, organizations can reimagine workforce planning to drive agility and growth.