Valuing data assets can be key to unlocking board-level support for data modernization and transformation

Fifty-five percent of Deloitte’s 2025 Tech Value survey respondents invest in data modernization. Leaders want proof of returns—explore approaches to define, measure, and communicate data value.

Alison Cuffari

Riddhi Acharya

Michael Le

Elizabeth Stein

Abed El-Husseini

Zack Grossenbacher

Organizations that treat data as assets and invest in data monetization are more likely to outperform peers and achieve two to three times the return on investment on key metrics, according to data collected from respondents in Deloitte’s 2025 Tech Value survey.

Data assets—from targeted data sets to contextualized insights and reusable AI models—are being productized to deliver repeatable business value, so assigning a fair market value to them should involve a clear, standardized approach. Typically income, cost, and market benchmarking are used, often in combination, and are adjusted for quality, rights, and context, because no single method fits all. Meanwhile, data value can be weakened by unmanaged “data debt” like life cycle costs, quality problems, compliance and data security risks, and data decay. Given how complex these factors may seem, it can be difficult to make the case for investing in data as an asset without a clear and concise way to convey both data value and costs with a straightforward metric. To help leaders quantify value, and monetize data assets practically, we combined the results from our 2025 Tech Value survey with specialist interviews, client case studies, and industry benchmarking to create a pragmatic framework designed to help leaders measure and report data value so that a C-suite or board can quickly grasp its ROI.

Defining data assets and their value drivers in an AI-driven market

Data assets can take many forms but are designed for consumption, built to create measurable, repeatable business value, and intentionally packaged (or “productized”) across three categories:

Targeted data sets (or products) expand the reach from domain-specific internal data sets to integrating external data sets and synthetic data. For example, companies like X (formerly Twitter) license access to application data through application programming interfaces for market research and trend analysis,1 while Foursquare monetizes location and foot traffic data for applications such as retail site selection and urban planning.2

Contextualized insights extend data sets by transforming raw data into actionable, decision-ready intelligence that helps solve specific business problems. For instance, Mastercard aggregates anonymized transaction data to produce consumer spending trends and analytics services for banks and merchants.3 Contextualized insights are shifting away from static dashboards toward decision services and closed-loop, real-time optimization.

Customized models and algorithms integrate machine learning-ready features, embeddings (which is how data is coded to convey its meaning), and synthetic data, along with tailored algorithms, designed to be reusable. For example, Uber AI Solutions provides enterprises with AI platforms and data foundries for training large models,4 while Salesforce’s Einstein platform offers extensible AI capabilities integrated with customer data and workflows.5 These models are increasingly managed like products, with versioning, monitoring, and outcome-based pricing.

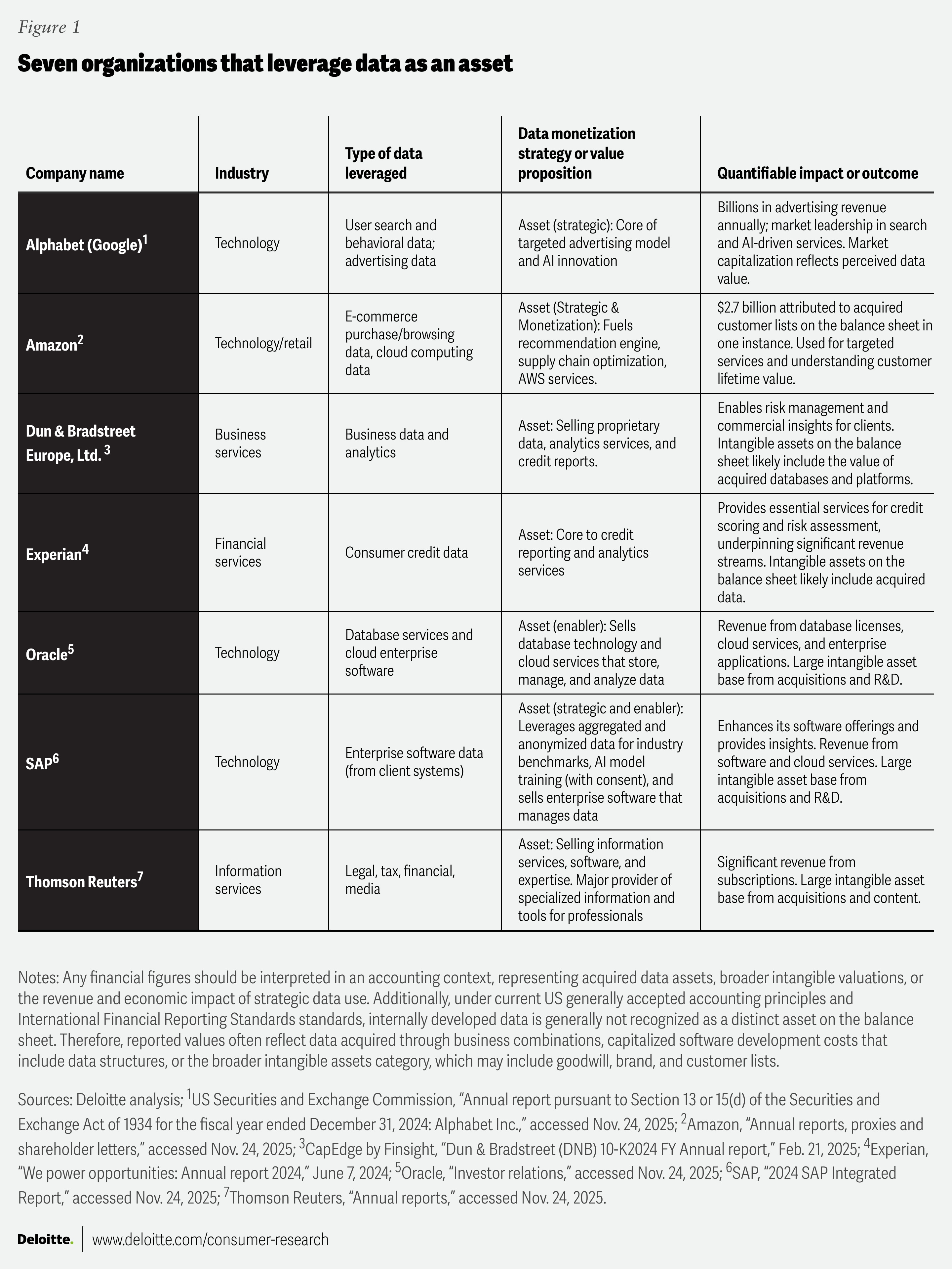

Data assets can serve both as operational enablers and as engines of strategic, financial, and resilient growth (figure 1).

What approaches can companies take to value their data assets?

A standardized approach to valuation analysis can help equip leaders with reusable benchmarking inputs and greater insight across multiple data sets, business lines, and revenue streams (data insights, operations, and platforms). These measures generally come back to the cost and economic dynamics driving the business case.

Most widely used valuation approaches are adapted from established valuation practices for other intangible assets: income, cost, and market.6 Each offers a distinct lens and tends to fit different data types and its purpose and use for the company.

The income approach

The income-based lens is commonly used when data directly affects cash flow. It converts expected future benefits from the data into today’s value. Within this lens, there are three practical methods that are often used:

- The multi-period excess earnings method starts by forecasting the after-tax cash flows attributable to the data. It then deducts charges for other assets that support those cash flows, like platforms, people, or brand, leaving “excess earnings” that are discounted to present value.

- The relief-from-royalty method values data by estimating the royalties the company avoids paying because it owns the data; those annual avoided payments are discounted over the asset’s useful life.

- The with-and-without (differential cash flow) method compares the company’s projected performance when using the data with its performance without it. The present value difference is the data’s contribution.

Each of these income methods typically maps to different scenarios. The multi-period excess earnings method is helpful when a company can reasonably isolate the data’s direct cash contribution. The relief-from-royalty approach tends to be effective when comparable licensing arrangements exist or when ownership clearly avoids recurring third-party costs. And the with-and-without method is useful when the value is best shown as the incremental revenue or cost avoidance that the data enables. For example, a waste technology company that used proprietary operational data to avoid licensing third-party data sets valued that benefit with a relief-from-royalty approach over a seven-year useful life. Similarly, an edtech company that measured incremental revenue enabled by external data sets used a with-and-without comparison to determine how much it should rationally pay for ongoing access.

The cost approach

The cost approach values an asset by estimating what it would cost today to recreate or replace it with something that provides the same utility. It distinguishes reproduction (an identical copy) from replacement (a functionally equivalent substitute) and builds the estimate from direct costs (like acquisition, engineering, data labeling, software, hosting, and platform costs) and indirect costs (such as overhead, storage, security, compliance, and governance.) Two additional components commonly applied under the replacement-cost method are:

- Developer’s profit, which captures a market-level margin that a third party would require to build the asset

- Entrepreneurial incentive, which represents the amount of economic benefit required to motivate the asset owner to enter into a “DIY” development process

Value conclusions under the cost approach are adjusted to reflect current utility rather than historical spending. Technological obsolescence can reduce value when newer methods produce the same output more cheaply, faster, or at higher quality. Economic obsolescence reflects external forces—interest rates, inflation, required returns, and supply-demand shifts—that lower expected margins or cash flows relative to historical levels.

For example, rebuilding a proprietary research database might require roughly US$1 million in researcher time, acquisition fees, data engineering, and platform costs. After applying developer’s profit, entrepreneurial incentive and obsolescence adjustments, the resulting figure provides a defensible, cost-based indication of value.

Here’s an example of a company we worked with—a real estate services firm that uses mortgage listing data ran two checks:

- An income-based method forecasted the returns the data would generate over several years, subtracted charges for other assets (like working capital, property, and staff), and converted those future cash flows into today’s dollars.

- A cost-to-rebuild approach added up hosting, listing-creation costs (staging, photos), outside broker hours, and data engineering, then added a developer profit margin and an entrepreneurial premium and reduced the total for obsolescence or lower quality.

In short, the firm measured “what our data will earn” (income) versus “what it costs to rebuild our data” (cost).

Why this approach? The cost result was used as a value benchmark: When both methods agreed, the valuation was deemed to be more credible.

The market approach

The market approach values an asset by looking at prices that were paid for similar assets in comparable transactions or observable market indicators, relying on the principle of substitution—a buyer typically won’t pay more than what a broadly comparable asset sold for. In practice, analysts adjust benchmarks for differences in scale, timeliness, granularity, completeness, data quality, provenance, usage rights, and any other constraints that affect economic utility.

For example, if a comparable customer data set sold for US$500,000, adjustments for size, recency, consent posture, attrition, and enrichment would yield a market-supported reference price for another database. That reference is useful, but because data is an emerging asset class, reliable and detailed transaction data are limited and many deals don’t disclose the key value drivers needed for clean comparisons.

As a result, the market approach remains conceptually valid but is rarely used alone for data valuations; it’s most helpful as a reasonableness check alongside income- or cost-based analyses that capture how the data actually contributes to business performance.

The reality of valuing data assets

How organizations apply these methods can vary considerably based on their industry and the type of data being leveraged. Because data can be used simulataneuously by many users, is context-dependent, and often synergistic across use cases, many organizations combine these approaches and supplement them with a qualitative assessment. As Douglas Laney notes in Infonomics, it can be useful to consider intrinsic attributes of data such as quality, completeness, scarcity, cost to transform, and business relevance.7 These considerations should inform the valuation analysis.

While it’s important to implement a standardized approach to valuing the economic potential of data as an asset, it’s also important to factor in the costs associated with data. Once assessed, managing data costs can be a critical strategy to manage growth relative to those expenses in order to leverage “data debt.”

What is data debt and how do you calculate it?

Just as leveraging data assets can drive growth, mismanaging them can create significant costs. Like the concept of technology debt, which refers to the future costs of shortcuts or suboptimal, short-term technology choices, data debt accumulates from poor life cycle management, data quality issues, risky data practices, and other systemic problems. Quantifying the value of this debt is essential for maintaining efficient operation and enabling better, faster decision-making.

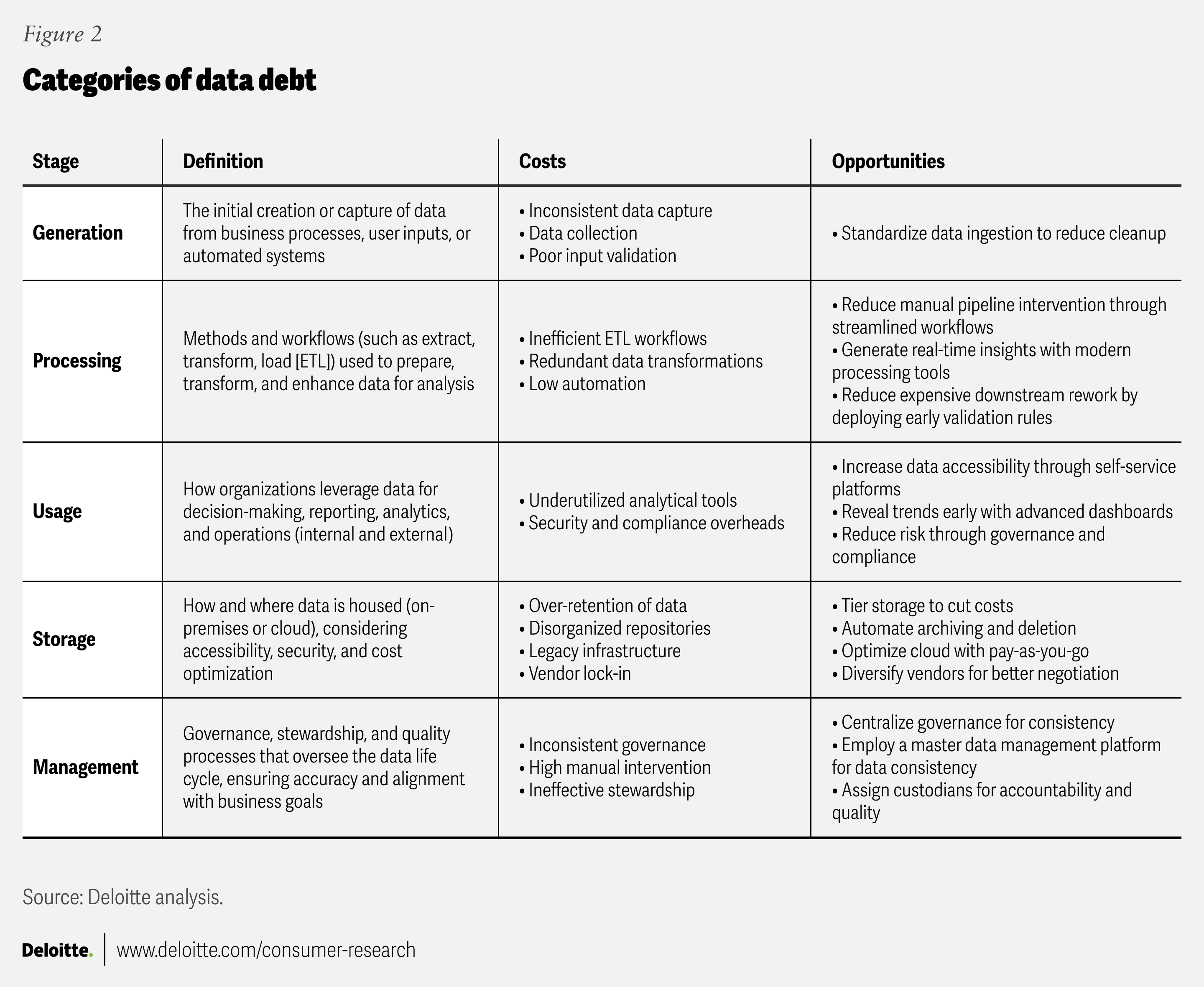

Data debt can be measured by evaluating an organization’s data needs and capabilities across the entire data life cycle, accounting for costs, risks, and liabilities tied to data generation, processing, usage, storage, and management. These include both direct costs (such as storage fees) and indirect costs (such as labor for data management). Opportunities to reduce data debt exist at every stage (figure 2).

Data debt can amount to substantial financial and strategic liabilities. These include the cost of data breaches, which can trigger direct expenses such as forensic investigations, legal fees, regulatory fines, and customer remediation, as well as indirect impacts like reputational harm and loss of trust. Noncompliance with data privacy regulations can result in severe penalties. Data decay, where data accuracy can degrade by roughly 25% per year,8 wastes marketing spending and may undermine decision-making. Poor data quality can also lead to ethical missteps, biased algorithms, and exposure.

Introducing ‘data debt leverage’

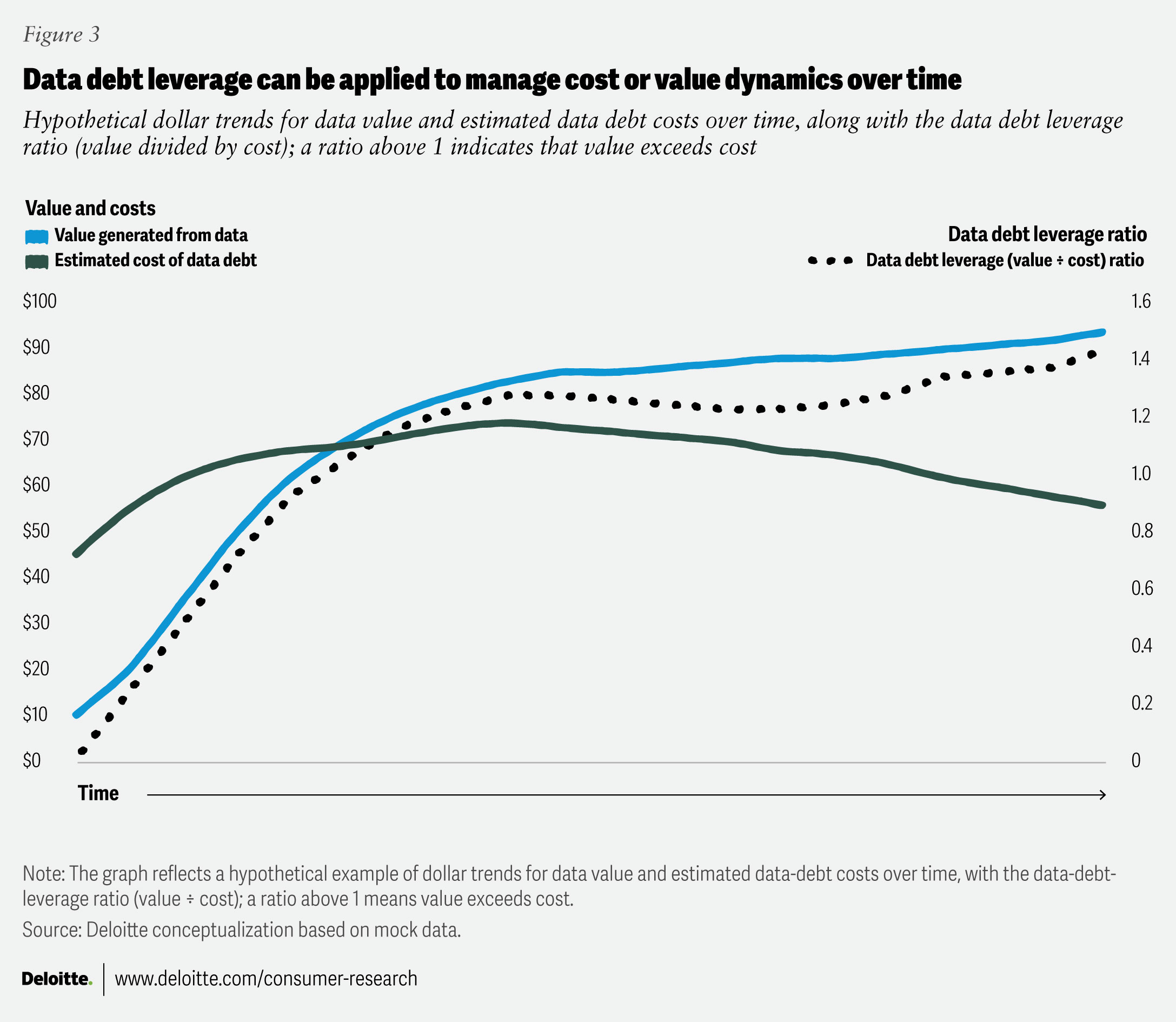

Here, a valuation technique that we call “data debt leverage” can help to manage downside risks. Data debt leverage is the ratio of the value of data assets to the total cost of data debt, including both the ongoing expense of managing legacy data and the investments needed to modernize or remediate systems. If the ratio is healthy (greater than 1), the value of data exceeds its total cost, balancing the retention of high-value assets against the drag of obsolete information. The goal is to maximize intrinsic value while minimizing burden by reducing costs, risks, and inefficiencies to enable smoother operations, stronger decision-making and more intelligent and agile businesses (figure 3).

In the example shown in figure 3, the starting value generated from the data was US$15 million and the cost to manage the data was US$45 million. The company’s data debt leverage ratio was initially poor. However, the company increased the data value incrementally over time while managing costs. Its data debt ratio eventually became healthy (above 1) by year three and for the next seven years. It’s important for companies to manage a healthy cost to value ratio to maintain data debt leverage.

Framing data investment for the board

As executives prepare to value their data assets, the highest‑value items could be data sets and models the company prioritized as strategic investments. Valuations should show the board the net return after accounting for data debt (the life cycle costs, quality gaps, and compliance risks that erode value) so leaders can see clearly which assets deserve more funding and which may require remediation.

Make the ask simple and measurable. Consider adopting a standardized valuation framework (income, cost, market lenses with quality and rights adjustments), reporting a single “data‑debt‑leverage” metric (value divided by estimated data‑debt cost), and funding a focused program to maximize data value while remediating the largest sources of data debt. That combination can help turn abstract concepts into board‑level decisions.

This publication contains general information only and Deloitte is not, by means of this publication, rendering accounting, business, financial, investment, legal, tax, or other professional advice or services. This publication is not a substitute for such professional advice or services, nor should it be used as a basis for any decision or action that may affect your business. Before making any decision or taking any action that may affect your business, you should consult a qualified professional advisor. Deloitte shall not be responsible for any loss sustained by any person who relies on this publication.