South Africa economic outlook, December 2025

Political uncertainty, US tariffs, and weak investment will keep South Africa’s growth subdued in 2025, but reforms and low inflation signal support for future gains

The start of 2025 had signaled much higher growth prospects for the South African economy; yet the first half of the year was marked by challenges, including a delayed and disputed national budget process, fragility in the coalition government (Government of National Unity, or GNU), 30% reciprocal US tariffs, and a subsequent waning of both business and consumer confidence.1

These drove real economic growth (on the production side) of only 0.1% in the first quarter and 0.8% in the second—or 0.7% year on year for January to June 2025.2

Eight industries grew in the second quarter compared with the first (all except construction and transport). However, only three grew year on year compared with the second quarter of 2024, namely, agriculture, forestry, and fishing; trade, catering, and accommodation; and finance, real estate, and business services.3

On the expenditure side, household and government final consumption expenditure grew by 0.8% and 0.7%, respectively, in the second quarter compared with the first. But gross fixed capital formation declined further by 1.4%, while exports dropped by 3.2%.4

South Africa to still see growth in 2025

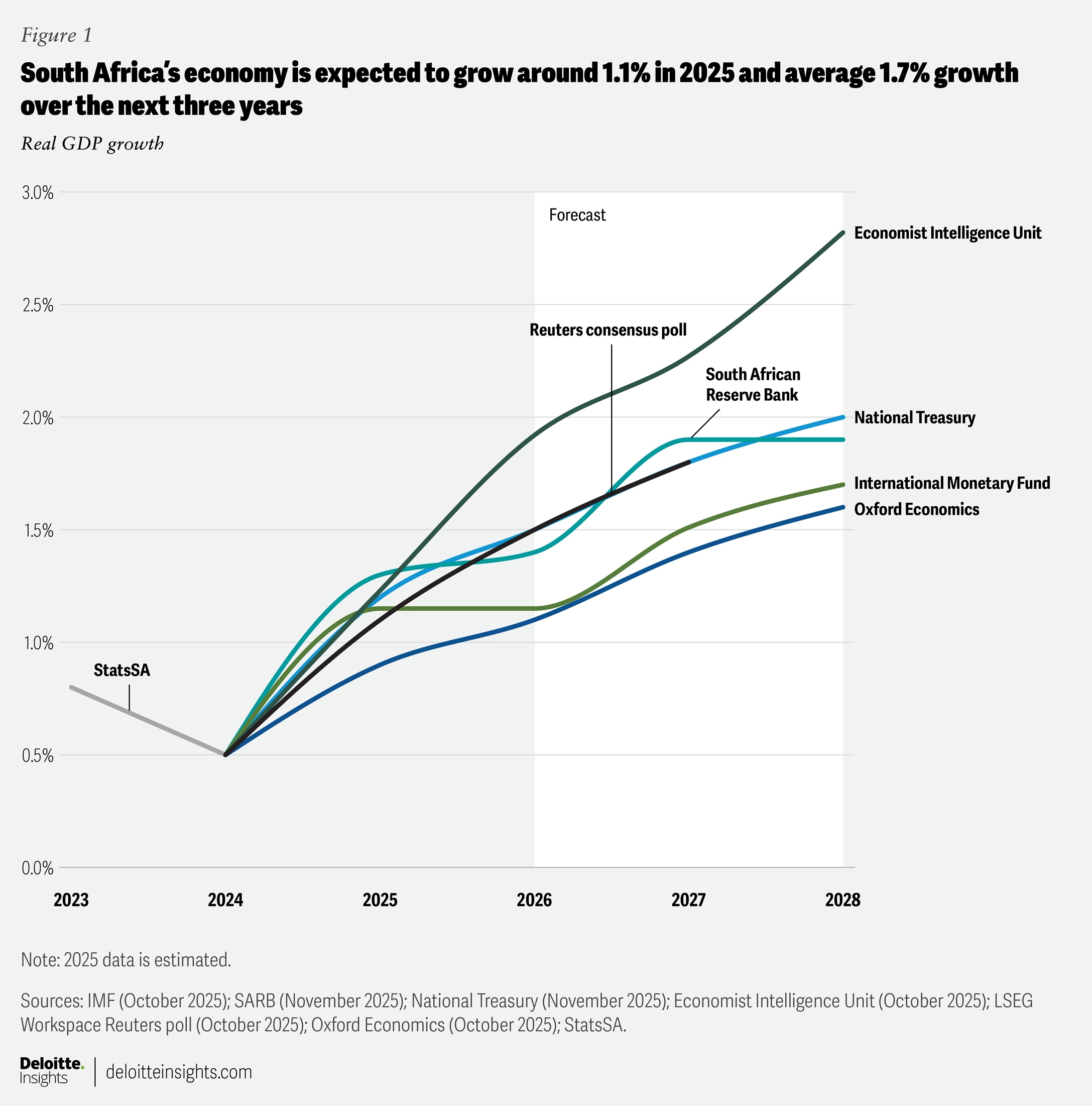

Various forecast agencies and a Reuters consensus poll put South Africa’s real economic growth at around 1% for 2025 (figure 1).5 Despite a real economic growth outlook of above 2% (nearing 3% in the medium term) from various forecasters, the International Monetary Fund recently warned that South Africa is unlikely to reach 2% real GDP growth before 2030,6 with a key ingredient of future growth—much higher gross fixed capital formation, or infrastructure investment—still notably absent.

Although public sector spending on infrastructure and fixed assets has seen three years of increases—following a five-year downturn from highs recorded in 20167—gross fixed capital formation is expected to record a second consecutive annual decline in 2025. However, there is an increasing focus on infrastructure spending.8

Of course, forecasting a medium- to long-term outlook does not come without possible surprises—both downside and upside. While 2025 seems set to be another suboptimal year for real GDP growth, there are some green shoots and key tailwinds supporting South Africa’s emergence from the low-growth trap it has been in for more than a decade.

Low inflation could drive looser monetary policy to support growth

With the South African economy not performing to its fullest potential—largely due to long-standing structural constraints as well as external and domestic uncertainties—lower demand has also driven a low-inflation environment, improving consumer purchasing power amid a cumulative 150-basis-point cut in the repo rate since September 2024.9

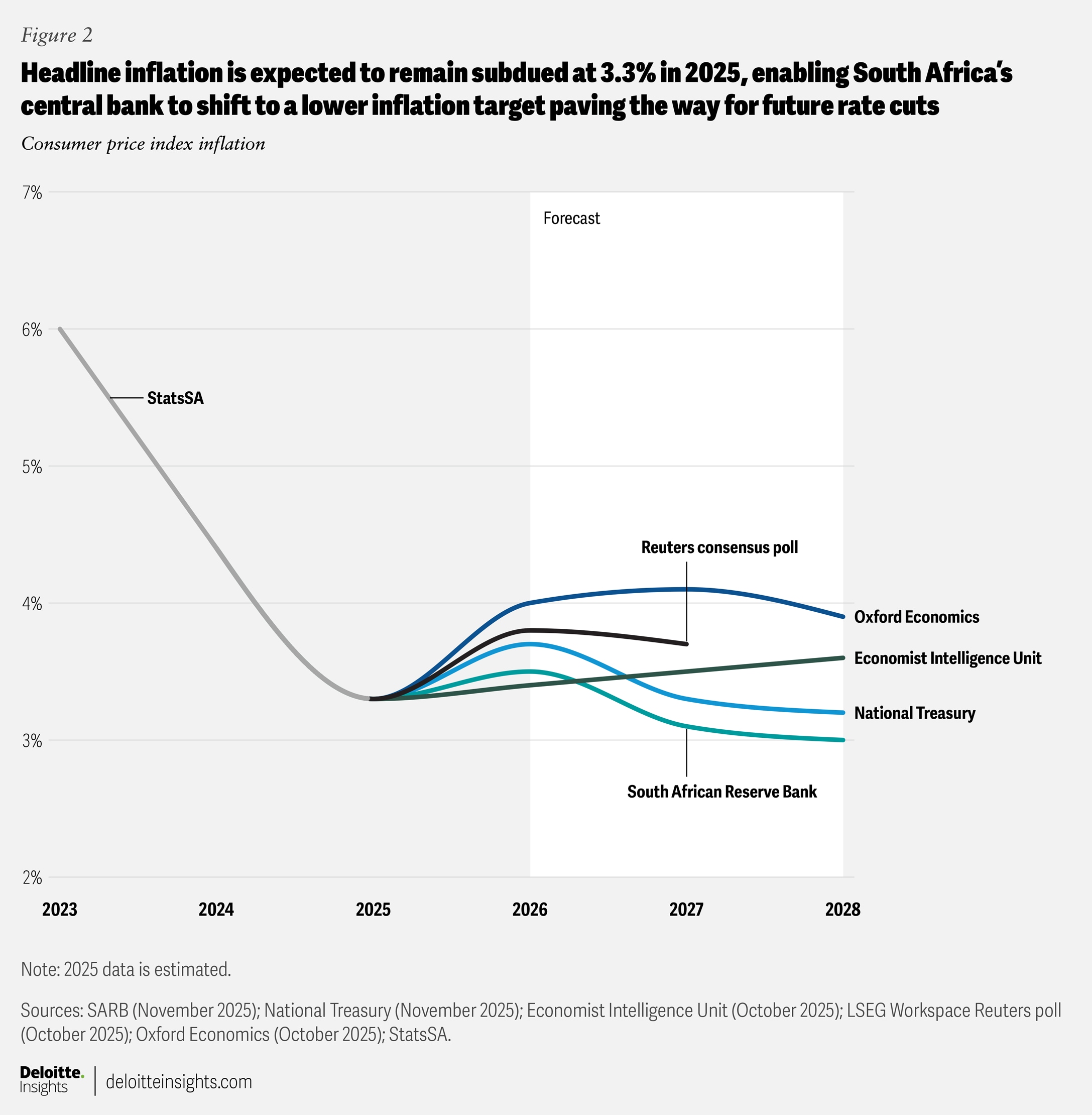

The monthly consumer price index inflation level was 3.4% for September and 3.6% for October 2025, with inflation for January to September 2025 averaging 3.1%10 and likely settling at 3.3% for 2025, according to the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) (figure 2).11 This is at the lower end of the inflation-target band (3% to 6%) and below the 4.5% midpoint. The moderating inflation environment has seen the SARB signal its preference for a lower inflation target—moving from a band to a point—at 3%, with a 1% tolerance band to provide flexibility for unexpected shocks.12 This was confirmed by the Minister of Finance in the Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement (MTBPS) on Nov. 12, 2025, with implementation of the new target planned over the next two years.13

The SARB expects that, by targeting inflation, the repo rate could dip to 6% by 2027. The repo rate was lowered by 25 basis points on Nov. 21, 2025 to 6.75%—a cut that was largely expected.14 This provides tailwinds for business confidence and consumer activity. However, key risks to this stance remain, including anchoring inflation expectations at 3%, particularly for administered prices and, more broadly, in the public sector, where annual inflation has averaged above 7% since 2009.15

Reform momentum continues, building confidence

While structural and economic reforms have been ticking along, one of the most important outcomes, as of late October 2025, was South Africa’s exit from the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) “gray list.”

After being gray-listed in February 2023 due to strategic deficiencies in countering money laundering and terrorist financing, as well as weaknesses in law enforcement, prosecution, and transparency, South Africa was placed under increased FATF monitoring and required to implement a 22-item action plan to address these shortcomings.16

The gray-list exit has been welcomed by both the government and the private players, with the expectation that increased compliance and focus on tackling crime and corruption will help reduce transaction costs, boost investor confidence, and unlock investment.17

Reform momentum is also evident in the energy and logistics sectors, addressing not only historical impediments to growth but also restoring confidence in South Africa’s economic trajectory.

Following efforts to increase generation capacity and reduce loadshedding, the energy sector has shifted toward restructuring the electricity market. This includes advanced work to establish the South African Wholesale Electricity Market (SAWEM)—a competitive wholesale market—while continuing the unbundling of state-owned utility company, Eskom.18

The National Transmission Company of South Africa (NTCSA)—already carved out of Eskom—has recently completed a gap analysis of the systems and processes required for its role as market operator, with work underway to determine infrastructure and capacity required for operations.19

At the same time, training and accreditation are underway for future SAWEM participants to ensure that the skills base needed for a functioning wholesale market exists. Rules for the wholesale electricity market (or “the Market Code”) have been developed and will be submitted once the NTCSA obtains its market operator license.20

As the market prepares for these changes, there is also a significant pipeline of private sector renewable energy projects expected to be facilitated by the new market structure.21 Progress has also been made on South Africa’s Independent Transmission Project, a public-private partnership initiative to expand transmission infrastructure by at least 14,000 kilometers over the next decade to accommodate additional generation capacity. Requests for proposals are expected to be due soon.22

The other key factor dampening growth is the ports and rail sector. Inefficiencies and capacity constraints have undermined export competitiveness and driven up logistics costs. Prioritized reforms to modernize freight logistics—opening the sector to greater private participation and restoring operational performance—have included the allocation of rail network slots to 11 private train-operating companies across 41 routes this year. This marks a historic shift toward open access, while the development of a revised network statement and access tariff framework is set to establish fair and commercially viable terms for all operators by early 2026.23

Private sector involvement is also gaining momentum in the ports sector, particularly in container terminals, with new investment and management expertise. Similarly, the public-private partnerships unit has completed a review of market interest and is preparing the first requests for proposals for strategic rail and port corridors. Results from these reforms are already showing promise: Freight-rail volumes have increased by 5.5% year on year to over 160 million tons, reversing a multiyear decline. Port performance has also improved, with shorter vessel anchorage times and higher throughput.24

With the establishment of the Transport Economic Regulator and the unbundling of the National Ports Authority from Transnet on track for 2026, the sector is poised for further transformation—one that promises a more transparent and competitive environment. These reforms are laying the groundwork for a modern, efficient logistics system that will support South Africa’s growth ambitions and enhance its position in global trade, with an estimated 200 billion rand in potential investment over the next five years.25

Good fiscal governance could boost investor confidence

Government finances are also improving: National Treasury’s commitment to fiscal reforms and consolidation is starting to yield tangible results. As per the 2025 MTBPS, the government is on track to achieve a wider primary budget surplus than previously forecast for this financial year—a sign that expenditure is being contained—while tax revenues are expected to exceed budget estimates by about 19.3 billion rand, or roughly 1% higher than the 1.9 trillion rand forecast for 2025 to 2026.26

This is partly due to lower value added–tax refunds, better commodity prices (gold and platinum group metals), greater household spending, and a noted improvement in collections, bolstering state coffers. South Africa has already managed to run primary budget surpluses for two consecutive years, generating more revenue than it spent, excluding debt-servicing costs.

This trajectory is anticipated to continue, with the surplus projected to grow from 0.9% of GDP in this fiscal year to 2.5% by 2028 to 2029, while debt-servicing costs are projected to grow at nearly half the rate previously anticipated over the medium term.

This also means the budget deficit will narrow from 4.5% of GDP in this fiscal year to 2.7% in 2028 to 2029, with additional in-year adjustments to spending estimates made to address a possible funding shortfall in the next fiscal year.27

However, with economic growth lagging the interest rate on government debt, debt-servicing costs are still rising faster than GDP28—a dynamic that is unsustainable in the long term. If not addressed, South Africa could face higher tax requirements in the coming years. Nevertheless, National Treasury’s prudent fiscal management, consideration of a formal fiscal anchor, reduction of contingent liabilities (notably Eskom), and demonstration that it can boost revenue without raising tax rates, while focusing on combating illicit trade, have already borne fruit.

Two days after the MTBPS, S&P Global upgraded South Africa’s foreign currency long-term sovereign credit rating from BB– to BB, and its local currency long-term sovereign credit rating from BB to BB+, with a positive outlook.29 After years in sub-investment grade (junk) status with all three major rating agencies, and nearly two decades without an upgrade, this is certainly a positive development for South Africa (although Fitch kept the country’s rating unchanged, and Moody’s currently rates it the same as S&P Global, with a stable outlook).30

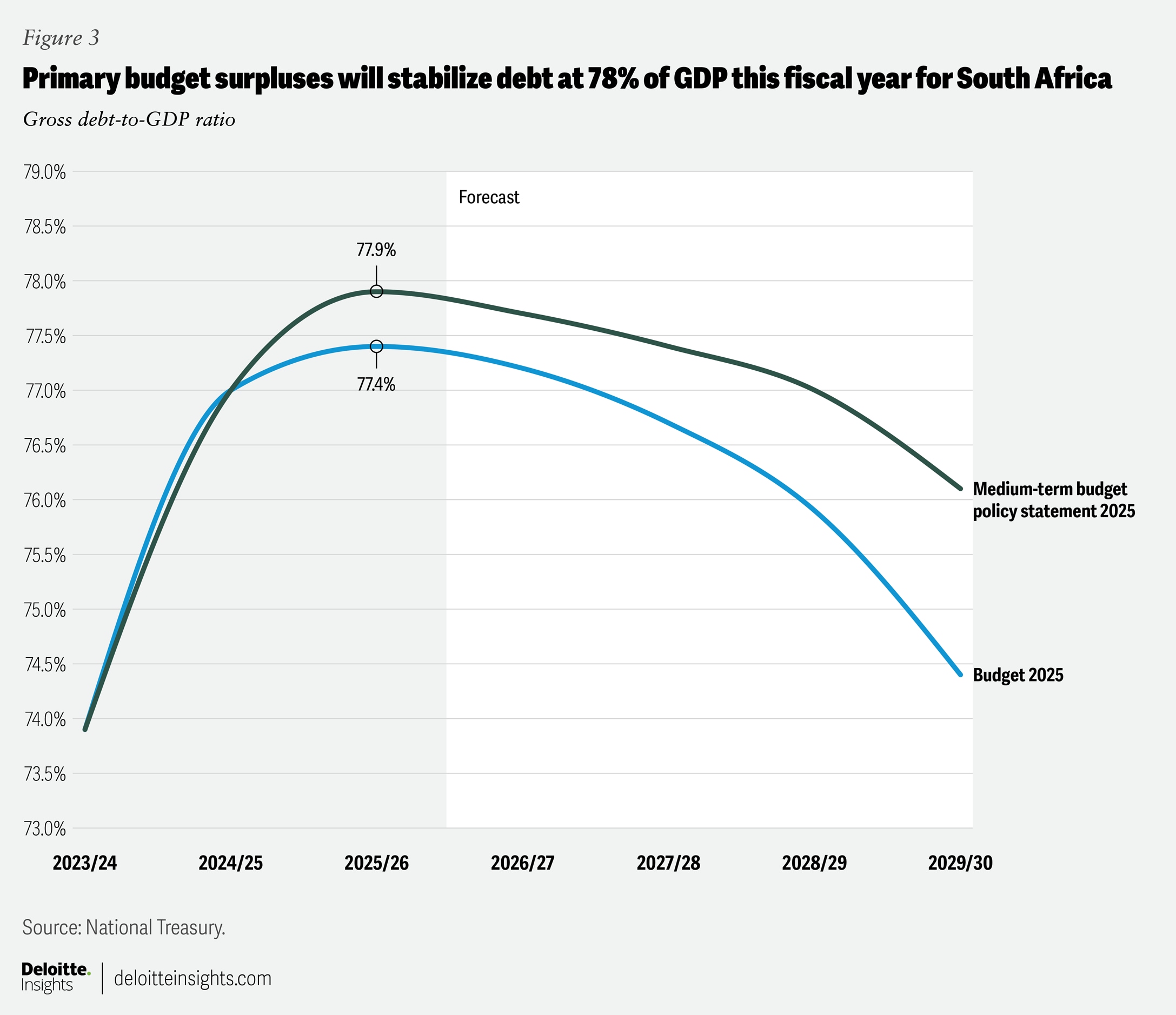

The junk rating has deterred institutional investment and contributed to capital outflows and currency weakness. However, a fiscal turnaround, coupled with a stabilizing debt-to-GDP ratio—which the MTBPS confirmed to be on track to remain below 78% this fiscal year—suggests that South Africa’s risk profile is improving faster than previously recognized (figure 3).31 Bond yields have also been on a downward trajectory from their April 2025 highs.32

These trends, supported by stronger economic growth, could help South Africa unlock a virtuous cycle of increased investment, economic tailwinds, and further fiscal improvement. This would not only lower borrowing costs but also restore confidence in the country’s long-term prospects.

Meanwhile, the GNU, while showing fragility earlier in the year, has signaled its intent to stick together. At a breakaway retreat in early November 2025, leaders of the coalition government adopted the medium-term development plan. The GNU’s five-year plan supports the focus on infrastructure reforms and investment in key sectors, with an overarching goal of driving job creation and reducing poverty while building an ethical, noncorrupt state.33

But challenges remain, besides crime and corruption

Corruption and crime remain a major challenge, with high-profile cases and ongoing incidents undermining public trust, deterring local and foreign investment, and constraining socioeconomic development, requiring greater momentum in criminal justice and governance reforms.

This also includes strengthening governance at the local level—an area that is a key focus of Operation Vulindlela Phase 2. Much needs to be done to bring many of South Africa’s 257 municipalities out of a state of disrepair as the country prepares for local government elections in late 2026.34

Restoring accountability at the local government level is important to ensure the continued delivery of basic services and infrastructure—such as water, electricity, and waste management—and to maintain social stability, besides supporting economic growth and development.

The World Bank announced a US$925 million loan to support eight municipalities as part of a program-for-results initiative in November 2025, with National Treasury to incentivize performance improvements and institutional reforms. It will be rolled out in eight cities, including Johannesburg, Tshwane, and Cape Town—home to more than a third of the country’s population and contributing about 85% of the national GDP.35

On the global front, South Africa still faces risks due to ongoing uncertainty within the global trading system, despite overall lower effective US tariffs than initially anticipated. At the time of writing, the country is yet to negotiate a better agreement for US market access post the 30% “reciprocal tariff” that took effect on Aug. 8, 2025 (with the sunset of the African Growth and Opportunity Act), which has affected the competitiveness of South African exports to the United States in sectors including agriculture, mining, and manufacturing.36

South Africa also hosted G20 leaders in late November, concluding its G20 presidency. The summit, the first on African soil, was a milestone for the country amid ongoing challenges. And despite the notable absence of the US president, the meeting will likely be remembered as an important political milestone for South Africa, its diplomatic capabilities, and its commitment to multilateralism and shaping international policy discussions to improve economic development in the country, across Africa, and in emerging markets.

The event also presented South Africa with the opportunity to strengthen relations with key global partners and to showcase the progress it continues to make in addressing growth-inhibiting structural weaknesses, demonstrating that the country remains open for business and determined to reverse its low-growth trajectory.