Japan economic outlook, January 2026

Japan has a delicate balance to strike—between inflation control and labor market health and wage growth—to avoid further economic deceleration in 2026

The Japanese economy contracted at an annualized rate of 2.3% between the second and third quarters of 2025.1 Much of it was due to a widening of the trade deficit, as exports to the United States fell while Japanese policymakers negotiated lower tariffs. Net exports, combined with falling private inventories, accounted for just over half of the contraction. This means other components also showed softness. For example, business fixed investment declined 0.8% on an annualized basis, and government spending fell 0.3%. Domestic final household consumption grew by just 0.3%, also on an annualized basis.2

Economic contraction and the underlying weakness of its components reinforce our view that growth is decelerating. This also likely reinforces policymakers’ decision to expand the budget. The package includes 17.7 trillion yen in new spending aimed at relieving price pressures on households and businesses, such as utility subsidies and wage support.3 The size of the stimulus is substantial, amounting to more than 2.5% of gross domestic product in new spending.

Fiscal stimulus runs counter to the monetary tightening that the Bank of Japan (BOJ) is pursuing. The BOJ is attempting to lower inflation, while fiscal expansion risks pushing it higher. Indeed, at its December meeting, the BOJ raised its policy rate to 0.75%—the highest in 30 years.4 Governor Kazuo Ueda noted that this rate was still below the lower bound of the neutral interest rate range. This suggests that the governor believes the policy rate should eventually move higher. Although the governor did not reveal what he believes to be the neutral rate range, the BOJ published a paper in 2024 that placed it between 1% and 2.5%.5

Interest rates are on the rise

These fiscal and monetary policies appear to be contributing to higher interest rates. While the BOJ is raising short-term interest rates, concerns about inflation and the sustainability of fiscal policy are likely contributing to higher long-term rates. For example, the yield on 10-year Japanese government bonds jumped above 2.3% in January—the first time since 1998.6 Interestingly, the value of the yen against the US dollar has steadily weakened since October despite the upward movement in interest rates,7 which may reflect concerns over looser fiscal policy.

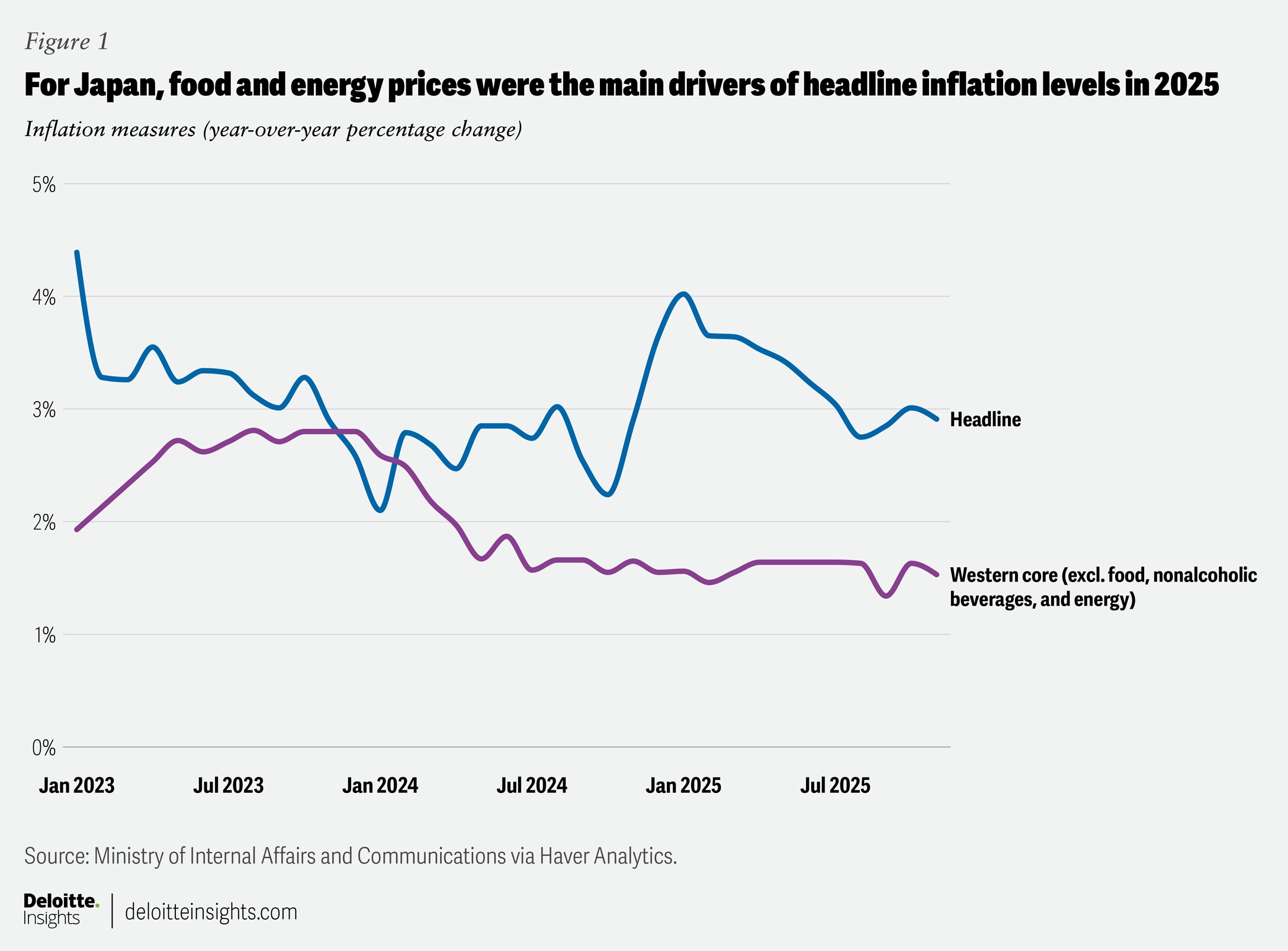

While the BOJ is signaling the possibility of further policy tightening,8 the pace of additional rate hikes is likely to be relatively slow. For example, we expect the next rate hike to occur in the middle of 2026, though a more marked weakening of the yen could lead to an earlier hike. The main reason for this cautious approach is that inflationary pressure remains subdued. Although headline inflation was above the central bank’s 2% target in November, at 2.9% on a year-ago basis, volatile food and energy components were the main culprits (figure 1).9

Fuel, light, and water charges rose 3.1% compared with a year earlier in November, while food and beverage inflation was 6% on a year-ago basis. Western core inflation, which excludes all food and energy, was just 1.6%, roughly where it has been for the past year.10

Fortunately, food inflation, while still high, is moderating relatively quickly. Food and beverage inflation on a year-ago basis fell from 7.4% in July to 6% in November. Energy inflation may also ease as oil prices continue to fall. For example, the Brent crude oil price fell below US$60 in December.

Outside of food and energy, most major inflation categories look relatively benign. For example, inflation in housing, furniture and household utensils, medical care, education, and miscellaneous items was all below 2% in November. Inflation in clothes and footwear, and culture and recreation stood at 2.3% and 2.4%, respectively; but both categories have seen moderating levels in recent months.11

Meanwhile, two of the BOJ’s three measures of underlying inflation remain below the 2% target. The above-target trimmed mean inflation was just 2.2% in November.12 Inflation pressures further up the pipeline also look benign. Import-price inflation has been in negative territory year on year since February 2025. In addition, producer price inflation moderated to 2.7% in November from 4.3% in March. The reading above 2% is largely due to agricultural products.13

The labor market remains strong, but risks are emerging

Although underlying inflation currently looks benign, it is possible that consumers will begin to increase their spending substantially, adding inflationary pressure to the economy. This is especially true given the announcement of fiscal stimulus. Indeed, consumer confidence in November reached its highest level since April 2025.14

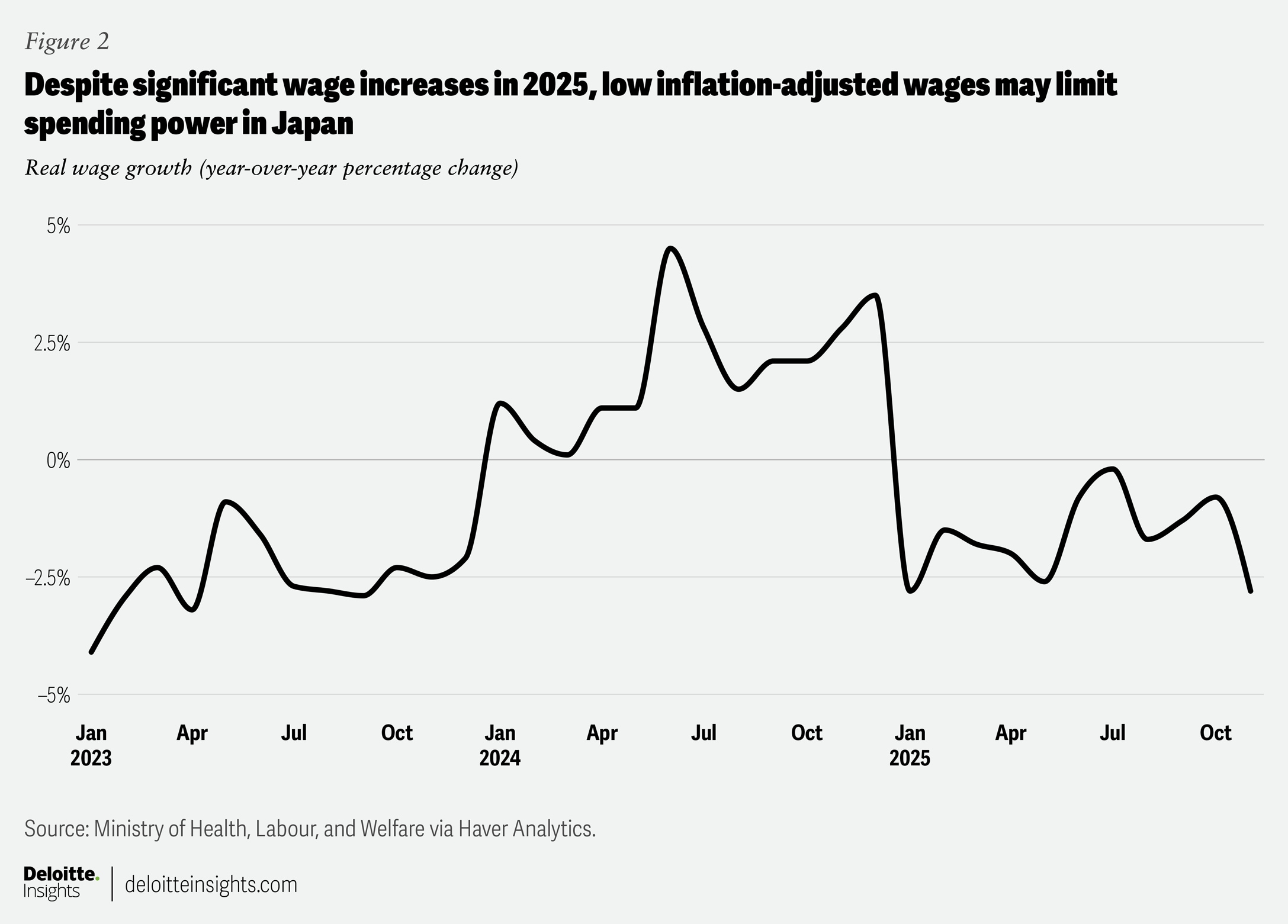

In addition, employment continues to grow relatively quickly, with nonagricultural employment up 0.9% from a year earlier in November.15 The unemployment rate has remained at a relatively low 2.6% for the fourth consecutive month in November, even as labor force participation continues to rise. Nominal contractual earnings growth for workers accelerated to 2.2% in November, up from 1.9% in September.16 Rengo, the country’s largest group of unions, plans to ask for a 5% wage increase during the 2026 shunto, the annual spring wage negotiation, the same increase it sought for in 2025.17 Last year, Rengo secured an average pay raise of 5.25%.18

This year, unions may not receive such strong wage increases. New barriers to US trade are challenging Japanese exporters and hitting profit margins. Stiff competition from China is adding further pressure on Japanese automakers,19 which could restrain wage growth.

With the number of job openings falling on a year-ago basis,20 some employers may be hesitant to offer more generous pay. Even if the pay increase is sizable, it will not necessarily lead to strong consumer spending. Inflation-adjusted wages were still down 2.8% from a year earlier in November,21 despite the sizable pay bump secured during the 2025 shunto (figure 2).

Despite these headwinds, many manufacturers have been feeling more positive about the economy. The Tankan business conditions index for manufacturers improved to 15in the last quarter of 2025—the highest reading since 2018.22 Small- and medium-sized manufacturers saw the largest gains during the quarter. Part of the improvement may be due to the United States lowering its tariffs on Japan from 25% to 15%. In November, exports to the United States were up 8.8% from a year earlier, after seven consecutive months of declines.23

However, there are signs that manufacturers’ optimism may be difficult to sustain. The rebound in exports to the United States is likely temporary. In addition, exports to China have slowed quickly. Exports to mainland China and Hong Kong combined were up just 1% from a year earlier in November—down from 10.4% in September.24 Ongoing challenges in China’s economy, coupled with geopolitical tensions between Japan and China, could further restrain Chinese demand for Japanese goods.25 The number of visitors from China and Hong Kong fell on a year-ago basis in November.26

Looking ahead, economic growth is expected to decelerate modestly in 2026. However, the magnitude of that deceleration will largely depend on the balance between fiscal and monetary policy. This will require bringing inflation down while maintaining a relatively healthy labor market and the solid wage growth that should come with it. Even so, this is a difficult balance to strike. Inflation is largely emanating from supply issues over which the BOJ has limited control. Meanwhile, fiscal stimulus could exacerbate inflationary pressures while contributing to concerns about debt sustainability.