South Africa economic outlook, June 2025

Domestic challenges and global uncertainty cloud South Africa’s economic outlook. With weak projections ahead, reforms and political stability will be crucial to reignite growth.

The signs around the end of last year pointed to a turnaround. A new coalition government promised policy stability. Loadshedding eased noticeably. Consumer confidence rose. Interest rates fell by 50 basis points in the second half of 2024. And more than 40 billion rand in retirement savings entered the economy through the new two-pot scheme. Yet, the momentum didn’t materialize.

South Africa’s real GDP grew just 0.5% in 2024, revised down from an early and already tepid estimate of 0.6%.1

Finance, real estate, and business services led growth at 3.5% (contributing the most to annual growth), followed by electricity, gas, and water, also at 3.5%.2 Agriculture, forestry, and fishing declined by 8%, for the second year in a row, while construction shrank by 5.1%, its eighth consecutive year of decline.3 A notable decline in agriculture, forestry, and fishing, in the third quarter of 2024 alone, was enough to pull down quarterly growth into negative territory.

Final consumption expenditure was up by 0.9% in 2024, driven primarily by household spending, which grew 1%. This modest uptick came despite persistently weak fixed investment, which declined by 3.7% after two years of growth, largely due to slower private sector investment.4 This was unexpected, given the supportive macro environment. The South African Reserve Bank (SARB) implemented cumulative rate cuts of 50 basis points in the second half of 2024—25 points each in September and November—bringing the repo rate to 7.75% by year-end.5 At the same time, consumer purchasing power improved as inflation eased, averaging 2.9% year on year in the final quarter. On an annual average basis, the headline consumer price index came in at 4.4%.6

Table of contents

- Structural fault lines are weighing down growth

- Budget tensions reveal fragile fiscal foundations

- Coalition politics are complicating reform momentum

- External shocks and global slowdown add to domestic pressure

- The less-than-rosy economic outlook for 2025

- Breaking South Africa’s decade-long trap of slow growth will take bold economic reform

Structural fault lines are weighing down growth

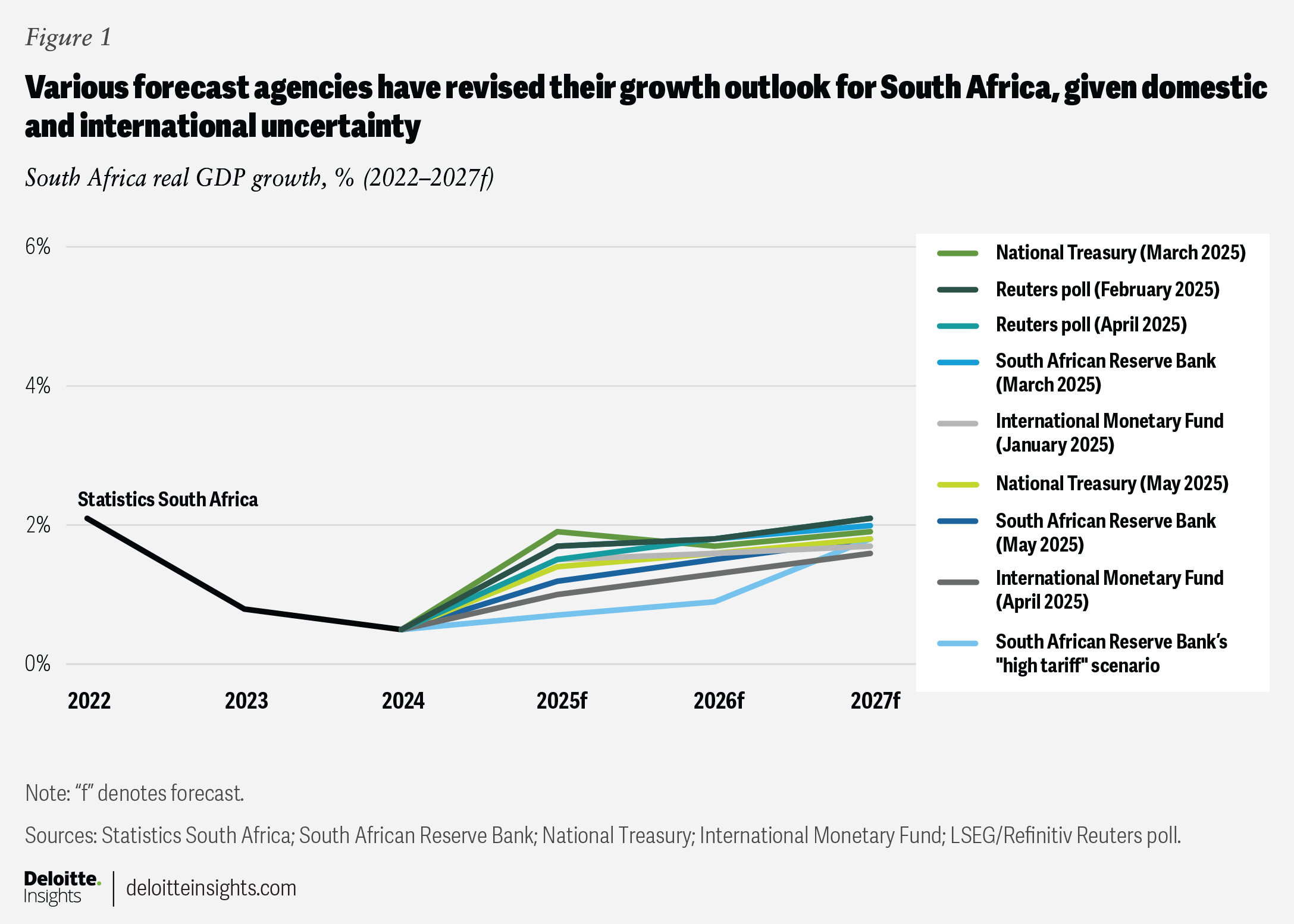

At the start of 2025, the economic outlook seemed more upbeat. Consensus forecasts projected GDP growth of around 1.7% for the year, with expectations of a gradual rise to 2% and above in the coming years.7 This optimism was underpinned by various structural and cyclical tailwinds, including improved energy supply, increased private sector participation in ports (with rail expected to follow), a further 25-basis-point interest rate cut in January,8 and over 40 billion rand in household withdrawals from the newly implemented two-pot retirement savings system by end of that month.9

The improving mood coincided with President Cyril Ramaphosa’s State of the Nation Address (SONA) on Feb. 6, 2025, which presented a narrative of progress—highlighting ongoing structural reforms, greater private-public sector collaboration, and plans for infrastructure investment.10 The SONA, however, also hinted at some cracks in the foundation, such as unfunded spending plans, all while South Africa continued to wrestle with a persistently high debt-to-GDP ratio.

Over the past decade, the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio has increased by nearly 30 percentage points, far exceeding the increases seen across emerging markets (17 points) and advanced economies (9 points).11 Fiscal slippage has been a key trend. The government’s strategy to reverse this trend has centred on achieving primary budget surpluses, as reaffirmed in the October 2024 Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement and the subsequent budget, to lower debt-service costs and reduce the crowding out of other forms of spending and investments.12

However, sustaining a primary surplus will require more than just revised targets—it demands real expenditure reform. It includes curbing inefficient and excessive spending, reining in public sector wage growth, limiting bailouts to state-owned enterprises, and overhauling public procurement systems as recommended institutions such as the International Monetary Fund.13 The IMF also recommended implementing a fiscal rule—which is a numerical limit—to help reinforce policy credibility, reduce the risk premium, and ultimately bring down the cost of borrowing.14

Budget tensions reveal fragile fiscal foundations

The 2025 budget process exposed just how constrained South Africa’s fiscal position has become and how economically and politically difficult it now is to implement revenue-raising measures.

The drawn-out process to pass the Budget has highlighted a core vulnerability in South Africa’s economic outlook: the limited space to raise new revenue, growing political resistance to unpopular decisions, and a rising debt-to-GDP ratio that is now approaching 80%.

Originally scheduled for Feb. 19, 2025, the National Budget was postponed after a leaked proposal to raise value-added tax by 2 percentage points (from 15% to 17%) sparked a coalition backlash. The proposed hike was widely criticized for its disproportionate impact on lower-income households, especially amid a cost-of-living crisis, and raised concerns about the lack of consultation with governing partners.15

In the following weeks, the Treasury attempted to soften the proposal, phasing in a value-added tax increase over two years (of only 0.5 percentage points each year).16 But large opposition parties still opposed the hike, and the Democratic Alliance (DA), alongside the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), filed legal papers against the proposed hike, to which the Western Cape High Court in April ruled in favour of, ahead of the anticipated tax hike on May 1, 2025. This led to the scraping of the proposal. By late May 2025, the Treasury had to table a third iteration of the budget,17 now focused on alternative revenue measures such as bracket creep, fuel-levy adjustments, and intensified tax-collection efforts to address an estimated shortfall of 75 billion rand.

This drawn-out process has highlighted a core vulnerability in South Africa’s economic outlook: the limited space to raise new revenue, growing political resistance to unpopular decisions, and a rising debt-to-GDP ratio that is now approaching 80%. Without faster growth or substantial spending reform, fiscal credibility remains under pressure, and the risk of future funding gaps and tax increases persists.18

Coalition politics are complicating reform momentum

While some argue that the tension arising out of the recent attempts at navigating fiscal policy within a coalition government reflect a maturing Government of National Unity, it has also highlighted fragility in the multiparty government, particularly the lack of transparency and collective decision-making.

The value-added tax issue also highlighted ideological differences regarding fiscal policymaking, with the DA advocating for fiscal reform and spending cuts, while the African National Congress–led National Treasury pushing for revenue measures to close the budget deficit. Tensions escalated when the proposed tax hike was taken to court, signalling that coalition partners are willing to confront one another through judicial means.

That three versions of the budget were tabled (the first version was not officially tabled but still released) in just three months signals broader governance strain. A lack of predictability, eroding trust, and weakening investor confidence point to a government struggling to act decisively in the face of economic pressures, further straining South Africa’s economic outlook.

External shocks and global slowdown add to domestic pressure

While South Africa has been grappling with internal fiscal uncertainty, the international environment has added a fresh layer of downside risks, particularly in its relations with the United States, a key trading partner and investor.

In February 2025, diplomatic tensions escalated when the US administration raised concerns over South Africa’s land reform policies. This led to a freeze on some bilateral assistance19 and, more consequentially, the imposition of a new set of tariffs in line with US tariff policy developments and announcements. Although some measures such as the reciprocal tariffs were later suspended, a 10% base tariff and a 25% tariff on automotive imports remain in effect,20 casting doubt over South Africa’s future access to the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) trade preferences.

Bilateral merchandise trade between South Africa and the United States has expanded notably over the past decade, from US$12.3 billion to US$15.2 billion.21 Today, South Africa’s exposure to the US market is significant in both scale and sectoral importance. In 2024, the United States accounted for 7.5% of South African exports—led by platinum group metals (PGMs, 33% of the export basket in 2024), motor cars (16%), unwrought aluminum (5%), ferro alloys (4%), and titanium ores and concentrates (2%).22

The automotive sector, in particular, is a key export from South Africa to the United States and has benefited from duty-free access under AGOA.23 Agriculture has also relied heavily on preferential treatment, with as much as 14% of fruit juice exports and 6% of wine exports destined for the United States.24 While some key mineral exports, such as platinum and titanium, have been exempt from the new tariffs due to South Africa’s strategic role as a supplier, manufactured goods (particularly in the automotive sector) and agricultural products remain more exposed.

The first-quarter data for 2025 once again pointed to stagnation. Real GDP grew by only 0.1% quarter on quarter (seasonally adjusted), indicating no meaningful expansion from the previous quarter.

Rising trade friction threatens these industries, along with the jobs they support—the timing is especially difficult. South Africa’s unemployment rate rose to 32.9% in the first quarter of 2025, up from 31.9% the previous quarter. Youth unemployment climbed to 45.1%. A loss of competitiveness in core export sectors could exacerbate these pressures, weakening the external balance, dampening manufacturing output, and further straining household incomes.25

Whether AGOA access is preserved or replaced with another preferential framework remains to be seen. Until then, the uncertainty surrounding tariffs and trade preferences adds yet another external constraint on South Africa’s already fragile and overdue recovery.

The less-than-rosy economic outlook for 2025

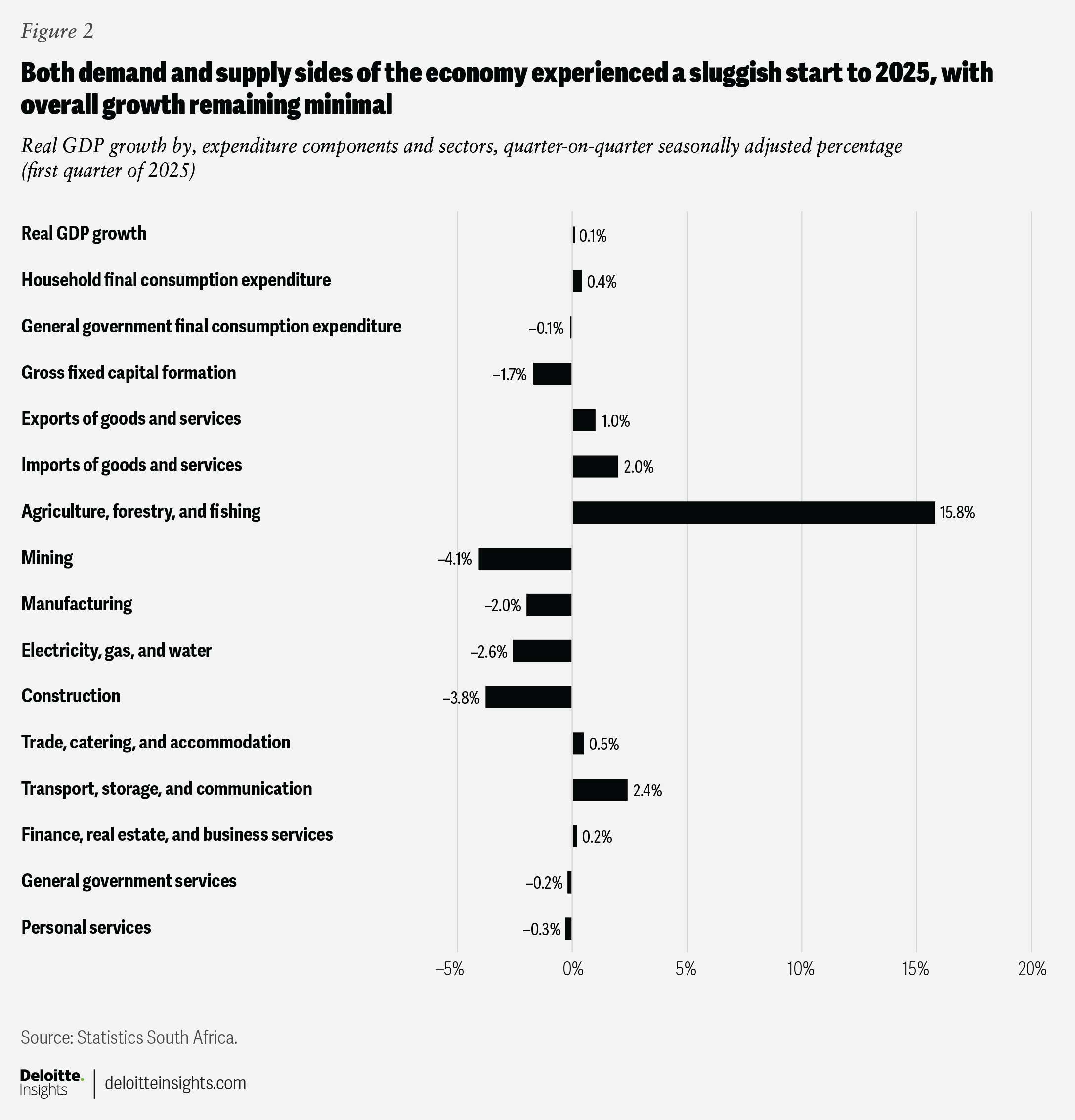

Amid global uncertainty and mounting domestic challenges, South Africa entered June confronted by first-quarter data for 2025 that once again pointed to stagnation.26 Real GDP grew by only 0.1% quarter on quarter (seasonally adjusted), indicating no meaningful expansion from the previous quarter. Only 4 of the 10 major sectors recorded positive growth. In fact, if not for the rebound in agriculture, forestry, and fishing—to 15.8% quarter on quarter (seasonally adjusted)—first-quarter real GDP growth was likely going to be negative. Notable decreases were recorded in mining (–4.1%), construction (–3.8%), electricity, gas, and water (–2.6%), and manufacturing (–2.0%).27

Many of the previous months’ business-data releases had already indicated weakness across sectors, particularly in mining, construction, electricity generation, and manufacturing.28 The ABSA purchasing manager’s index also moved further into contractionary territory (43.1), in May—for the seventh month in a row.29 Not only is this not an encouraging start to 2025, it also points to a likely a slow- to no-growth outcome in the second quarter of the year.

The SARB Monetary Policy Committee also factored in global uncertainty and weak domestic demand in its most recent interest rate decision in May 2025, although it was announced just days before the first-quarter 2025 GDP data release. The committee decided to cut interest rates by 25 basis points—its second of the year. With inflation coming in below 3% for several months in 2025—in fact below the midpoint of the inflation target band—there was room to lower the repo rate to 7.25%. Still, the bank acknowledged upside risks to inflation, stemming from the geopolitical environment and possible slowdown in global trade and growth, which could weaken the rand and threaten price stability.30

Breaking South Africa’s decade-long trap of slow growth will take bold economic reform

South Africa remains stuck in a slow-growth rut, held back by global uncertainty and long-standing domestic constraints. While the risk of punitive US tariffs has eased in recent months, geopolitical tensions, war, and global trade risks continue to weigh on the outlook.

More important are the binding constraints to growth at the domestic level. Loadshedding was largely expected to have been a thing of the past, given that reform initiatives included regulatory changes in the electricity sector that permitted private investment in electricity generation, as well as the restructuring of the power utility, Eskom.31 However, power outages and the risk of loadshedding have reemerged in the first quarter of 2025 (due to maintenance backlogs and grid mismanagement, rather than generational constraints). Ongoing challenges in ports, rail, and water infrastructure also persist, limiting competitiveness and frustrating efforts to build an export-led growth momentum.

The second phase of Operation Vulindlela, launched in May 2025, seeks to accelerate delivery across three key areas: electricity, water, and digital communications.32 The South African cabinet recently approved the Roadmap for the Digital Transformation of Government, which sets out a focused plan to modernize delivery of government services through investment in digital public infrastructure. If the program is successfully implemented, the Bureau for Economic Research has previously estimated that real GDP growth could increase to 3.5% by 2029 (that is, 1.5 percentage points over the baseline forecast);33 although in the short term, their own forecasts have also become much less bullish.34

Complementary analysis by the International Monetary Fund notes that broader reforms to South Africa’s business regulation, red tape, and governance could arguable yield the most dividends in terms of growth, investment, and employment creation, lifting medium-term output gains by as much as 9%.35

However, perhaps the most critical constraint is no longer diagnosis; it is implementation. South Africa has long been adept at coming up with promising plans for reforms, but inconsistent execution continues to hamper progress. Even as reform-based initiatives continue to tick along incrementally, there is growing urgency for South Africa to forge internal unity to strengthen external engagement and sustain and build much faster momentum on overcoming domestic challenges.