India economic outlook, January 2026

For India, 2026 will be the year of ‘resilience’ in domestic demand, decisive ‘reforms’ in fiscal, monetary, and labor policies, and ‘recalibrations’ in trade policies

The year 2025 marked an inflection point: Policy overhauls across Western economies—particularly in trade, investment, and industrial policy—triggered spillover effects across all major global markets. India was not immune to these shifts. Intricately connected to global value chains, India, the world’s fourth-largest economy and a major global trading partner, faced external shocks and acute effects from these global policy changes, including tariff escalations and volatile capital flows.

Yet, despite headwinds, demand resilience, a reset in trade and investment outlook, and policy reforms stood out. India focused squarely on its biggest strength, domestic demand, to keep growth buoyant as inflation levels stayed low at 1.8% on average through the fiscal year.1 With slowing global demand, rising trade frictions, and a delicate domestic consumption environment, India deployed a carefully sequenced set of fiscal, monetary, and trade reforms that not only cushioned the economy but also laid the foundation for future growth.

Much of 2025 efforts comprised managing external shocks and strengthening domestic fundamentals. Consequently, a major milestone came in August 2025, when S&P upgraded India’s sovereign rating from BBB– to BBB—its first such upgrade in 18 years.2

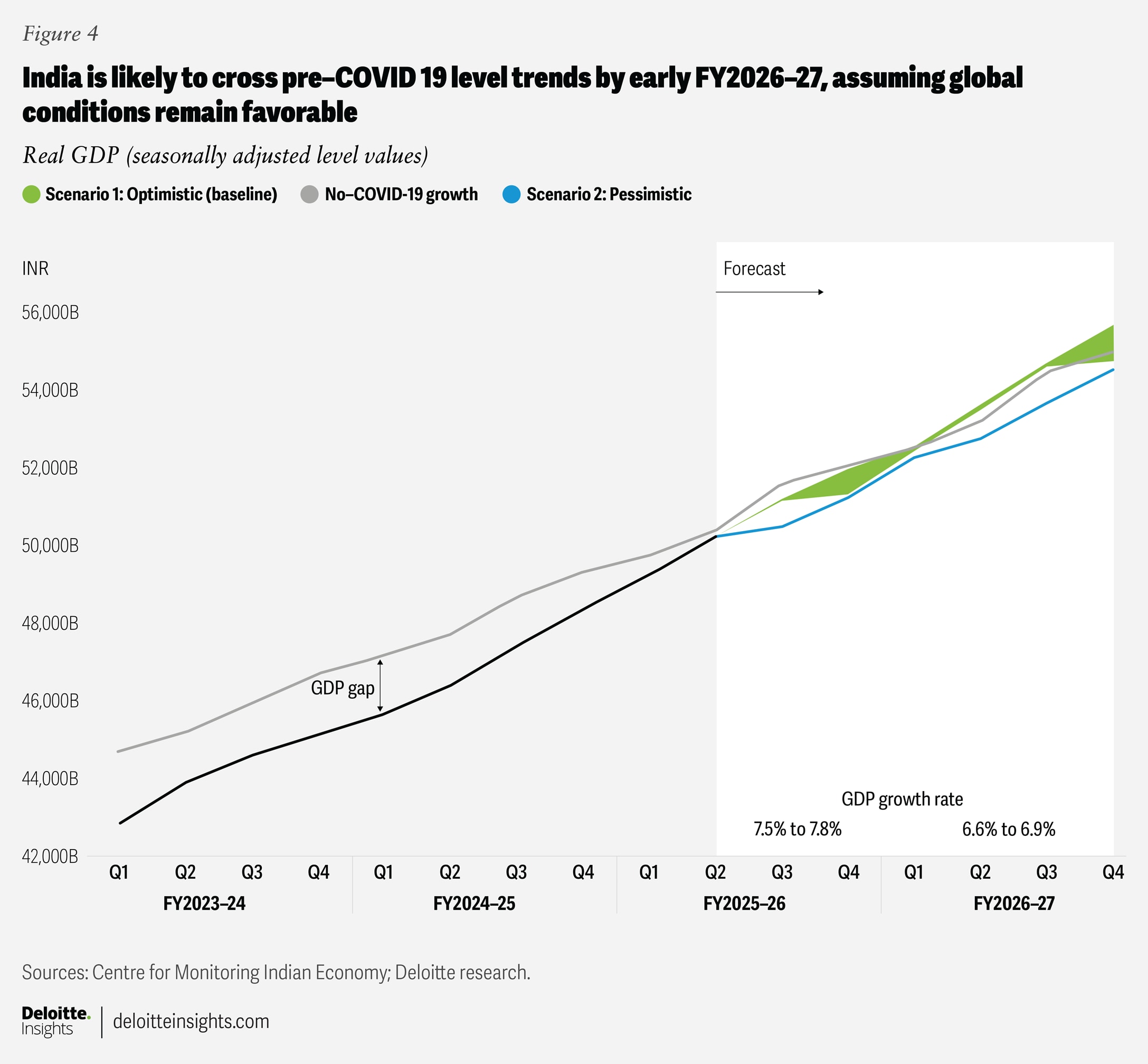

As India enters 2026, several themes will shape the next phase of growth and demand the same level of pragmatism. We expect full fiscal year growth to be revised substantially upward, as third-quarter numbers are likely to remain strong due to festive spending. Growth is expected to stand between 7.5% and 7.8% in fiscal 2025 to 2026, and then between 6.6% and 6.9% in fiscal 2026 to 2027, buoyed by the rollout of new goods and services tax (GST) rules and slowing inflation.3

India’s domestic demand resilience

India’s economic value expanded by 8.2% year over year in the second quarter of fiscal 2025 to 2026,4 reinforcing expectations of an upward revision in full-year growth. Despite global headwinds such as higher US tariffs and volatile capital outflows, India posted an impressive 8% growth in the first half of the fiscal, powered by robust private consumption and investment, aided by easing inflation and favorable rural conditions.

Key drivers

- Consumption: Private final consumption expenditure grew by 7.9% in the second quarter, supported by the lowest inflation level of 1.7% seen in a decade, rising disposable incomes from tax and GST relief, and better rainfall. Consumption grew by 7.5% in the first half of the fiscal.5

- Investment: Government capital expenditure utilization rose to 51.8% in the first half of the fiscal year (versus 37.3% last year), boosting gross fixed capital formation growth to 7.6% (versus 6.7% last year).6

- Sectoral strength: Gross value added (GVA) grew by 8.1% in the second quarter of the fiscal year, with manufacturing up 9.1% and services surging 9.2%, led by financial and professional services.7 GVA growth for the first half of the year came in at around 7.8%.8 Services now contribute 60% of GVA and 48% of exports, underscoring their strategic role.9

- Exports: After a strong first quarter, exports moderated in the second due to higher US tariffs on Indian exports (including a 50% tariff on select goods). But a trade rebound is expected, supported by upcoming trade agreements with the United States and the European Union, as well as diversification into services, electronics, and pharmaceuticals.

Growth momentum in Q3 is expected to continue to be strong, supported by resilient domestic demand. High-frequency indicators, including strong consumer confidence, vehicle registrations and sales, and easing inflationary pressures, point to continued support for economic activity. However, some external indicators such as currency depreciation and FPI outflows show emerging signs of stress, posing downside risks to the outlook.

Policy reforms

At the start of 2025, there were indications of macroeconomic stability: Inflation was tapering, the fiscal deficit was on a consolidation path, and growth levels were stable. However, there were early signs of economic strain as global policy and political relationships were changing fast, with clear effects on export prospects and real incomes. Policymakers recognized early in the year that if external demand were to weaken further, domestic demand stimulation would be imperative.

Fiscal

The year opened with optimism as the Union budget 2025–202610 signaled bold intent rather than scale. The government announced long-awaited direct tax exemptions for the middle-income class, which was under stress from persistent inflation, a modest post–COVID-19 labor market recovery, and elevated borrowing costs. By reducing personal tax burdens, policymakers aimed to lift disposable incomes, revive discretionary spending, and support small businesses reliant on domestic demand.

As global headwinds intensified through April 2025, the US decision to raise tariffs on select Indian goods added pressure on micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) and labor-intensive sectors such as seafood, textiles, apparel, and auto components.

In response, the government accelerated a key reform—the rationalization of GST slabs—ahead of the festive season to boost domestic demand (offsetting low export demand), aid informal sector recovery, strengthen tax compliance, and increase consumer spending.

With these measures, the government maintained high public capital expenditure (3.4% of gross domestic product in the first half of fiscal 2025 to 2026),11 particularly in infrastructure and green-transition projects like investments in renewables, ensuring domestic demand was the central growth pillar.

India has consolidated expenses, and the fiscal deficit is targeted at 4.4% of GDP this fiscal year,12 down from pandemic highs of 9.2% in fiscal 2020 to 2021. Disciplined expenditure management and buoyant revenue streams have, so far, helped government pursue growth-supporting measures.

Going forward, reforms—including the rollout of GST 2.0 and tax-relief measures—are unlikely to derail this trajectory. Higher nontax revenues, driven by an accelerated disinvestment pipeline and strategic asset monetization, are expected to offset potential shortfalls, ensuring fiscal prudence alongside growth.

Monetary policy

The government and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) remained aligned in their resolve to strengthen domestic demand. While fiscal policy focused on boosting consumer spending through tax relief and public investment, monetary policy provided liquidity and cost-of-capital support needed to sustain the recovery.

Through 2024 and early 2025, India experienced an unexpected slowdown in credit growth, particularly in personal loans and small-business lending. The RBI recognized that, without stronger credit transmission, consumer spending recovery would lose momentum.

In response, the RBI delivered one of the sharpest easing cycles in recent history, cutting policy rates by a full percentage point within four months starting in February. With food inflation cooling sharply and global energy prices stable, the central bank used this window to shift decisively from prolonged tightening to an accommodative stance.

Still, credit expansion remained subdued, with bank credit growth stuck near 10%.13 This incomplete transmission likely contributed to the RBI’s additional 25-basis-point rate cut in the final policy review of 2025, even as macroeconomic fundamentals strengthened. The final cut signaled a commitment to sustaining domestic demand through 2026 amid global uncertainty.

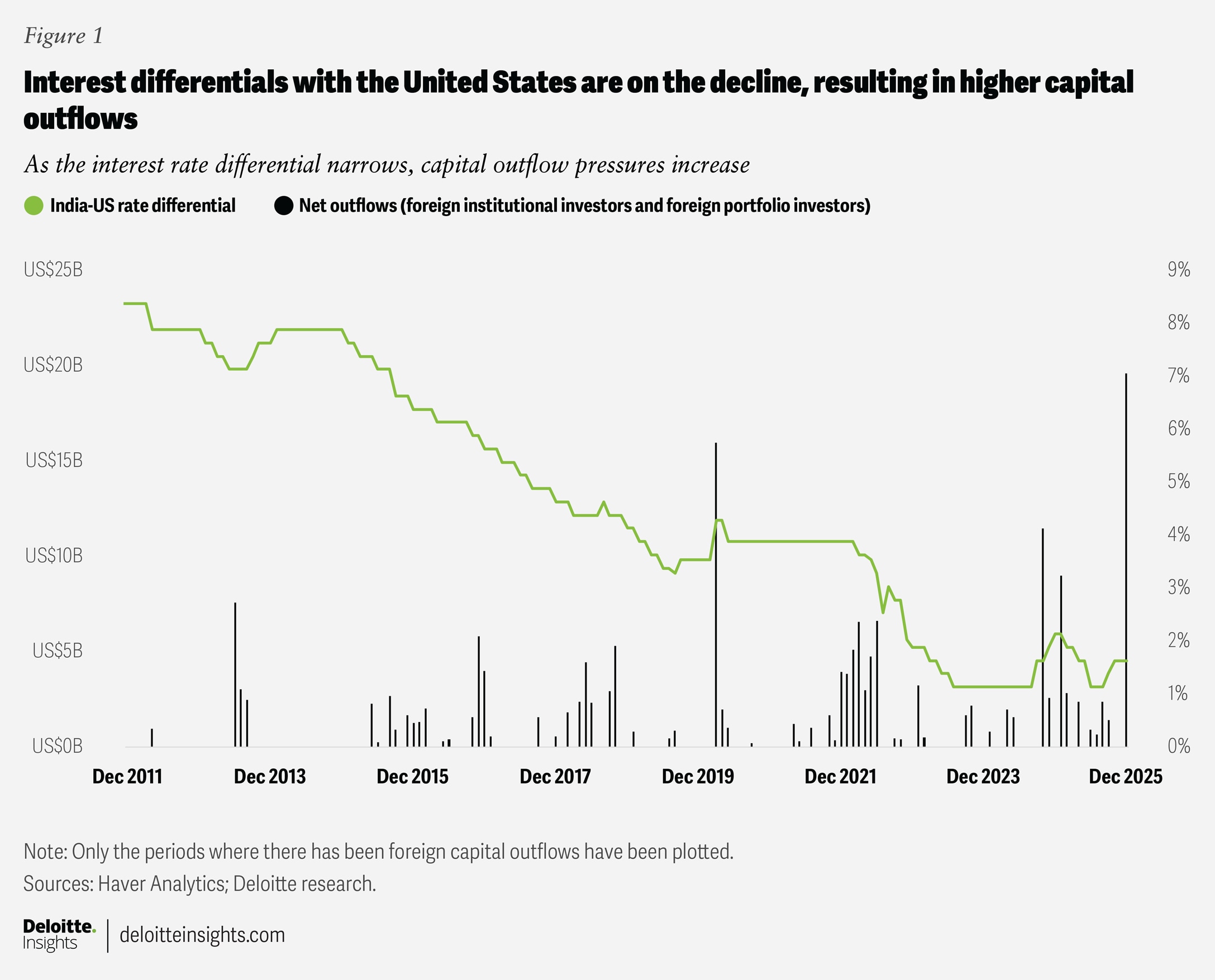

The RBI’s policy easing is, however, not without concern. The India-US policy rate differential has narrowed to about 1.625 percentage points after the two countries decided on policy rate cuts in December. The 10-year bond yield differential remains within a 2.5% range. The differentials are close to their narrowest levels in a decade, raising the potential for capital outflows from India as investors seek higher yields when investing out of the United States (figure 1). Reinvestment of earnings has declined, while repatriations have increased in the past year.14 In 2025, foreign portfolio selling aggravated, with markets seeing close to US$18.4 billion in net foreign portfolio investment outflows during 2025 (as of Dec. 12, 2025)—the highest seen in 15-years.15

Recently, such investment withdrawals contributed significantly to currency depreciation—with the 90 rupees per US dollar mark being crossed. While the Indian rupee is expected to stabilize as the RBI intervenes in the market to contain volatility, persistent outflows and rising outbound foreign investment could pressure foreign exchange reserves and keep the rupee weaker in the near term. The good news is that amid volatility in foreign capital flows, strong retail participation in the capital market has helped stabilize market valuations despite foreign investment outflows.

Labor

In 2025, an important structural reform milestone was achieved, with the long-pending labor codes—tabled four years earlier and delayed by extended consultations—finally coming into force. By simplifying compliance while safeguarding worker rights, the reform is expected to improve ease of doing business, accelerate job formalization, and attract fresh investment across manufacturing and services.

Trade recalibrations

Even as domestic reforms advanced, 2025 was equally shaped by complexities in India’s external economic engagements. Throughout the year, India worked to deepen traditional partnerships while expanding into new geographies to diversify its trade and investment profile.

2025 emerged as a pivotal year for India’s trade strategy, with the conclusion of several significant agreements that materially expanded its global economic engagement. India signed key agreements with the UK, New Zealand, Oman, and initiated negotiations with Israel, while the EFTA deal went operational in 2025, all aimed at diversifying export. Collectively, these agreements enhance market access across diverse regions and reinforce India’s ongoing efforts to diversify trade partnerships, investment flows, and export opportunities.

However, with limited demand-side policy levers remaining, the next phase of reforms must pivot toward supply-side improvements. This shift is essential to sustain momentum and build resilience against external shocks.

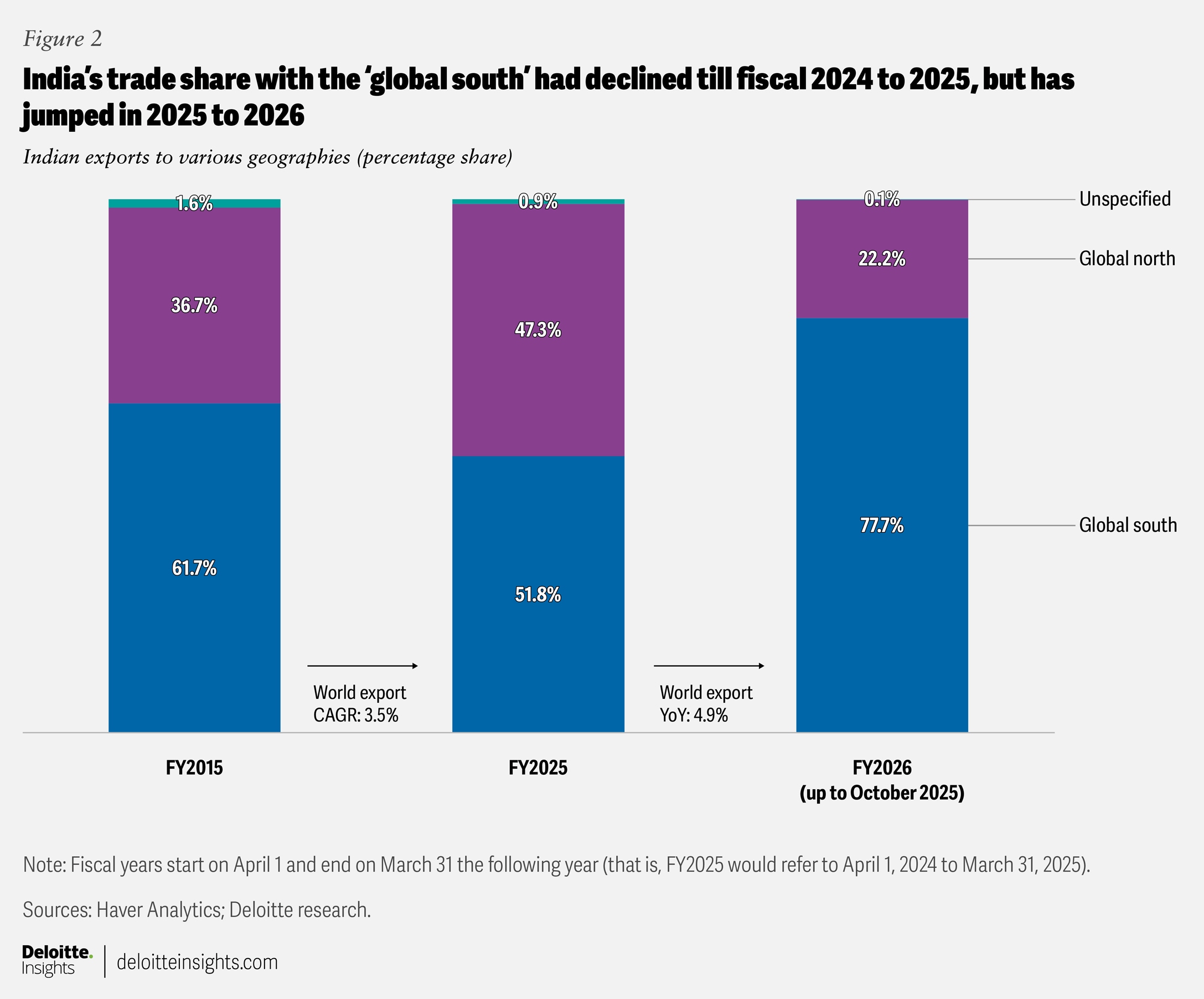

In 2025, India also expanded its trade outreach across emerging markets (figure 2). These regions now account for nearly 85% of the world’s population and close to 40% of global GDP.16 Going forward, trade corridors linking South Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Middle East are projected to grow nearly 4% faster than the global average.17 There is growing recognition that global commerce is shifting toward greater trade, investment, and innovation within the “global south,” with long-term implications for supply chains, digital services, and new agreements.

India is expanding its reach across Africa, Latin America, and West Asia, and recent BRICS and G20 engagements have focused on collaboration in energy, critical minerals, and digital infrastructure.

All eyes are on the much-anticipated US-India trade deal. Recurring delays in the deal (at the time of writing) continue to be a concern. The agreement, which had been expected to boost bilateral trade and improve market access for key sectors, remains pending, creating uncertainty for exporters. Until the deal materializes, export growth for goods is likely to stay moderate, while exposing services exports to uncertainties in the long run.

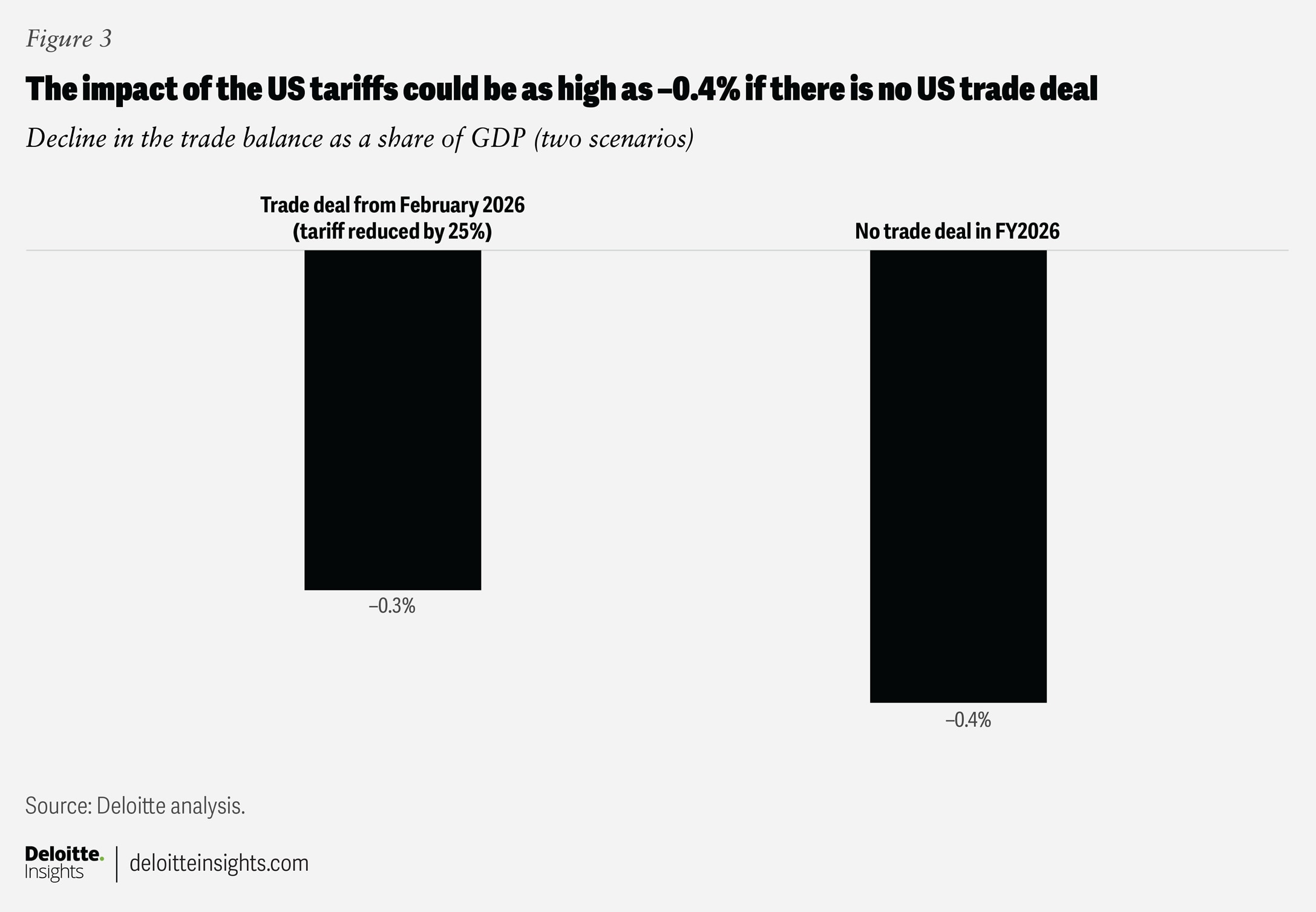

Under two different scenarios, we expect the impact of US trade tariffs on Indian exports to range between 0.3% and 0.4% of GDP (figure 3).

India’s economic outlook for fiscal 2025 to 2026

Much of 2025 was about managing external shocks and strengthening domestic fundamentals. As India enters 2026, it will have to carefully manage both global and domestic risks.

Three of the biggest global risks for India in 2026 will come from:

- US tariff policies and the conclusion of the India-US trade deal, which remains unpredictable.

- China’s slow recovery and its dominance in critical minerals, which India must monitor as it recalibrates its relationship with Beijing.

- Geopolitical tensions in Central Asia that could disrupt commodity prices and key logistics routes, including the Red Sea corridor.

Domestically, the three biggest risks that need to be monitored are:

- Poor transmission of policy rate cuts to credit growth.

- A resurgence of inflation as demand picks up fast (and core has been above 4%).

- Possible implications of lower tax revenues for fiscal consolidation this year.

We expect stronger economic growth in the third quarter due to festive demand and spending between October and December, followed by somewhat modest growth in the last quarter (unless the US trade deal concludes, ushering in trade and investment).

In Deloitte’s optimistic scenario (see “Key assumptions for Deloitte’s projections” for all scenarios), growth in fiscal 2025 to 2026 is likely to be between 7.5% and 7.8% (figure 4). A higher base and continued challenges in the global economy will likely keep the growth of the subsequent fiscal more modest.

Union budget expectations: A pivot from demand-pull to supply-push

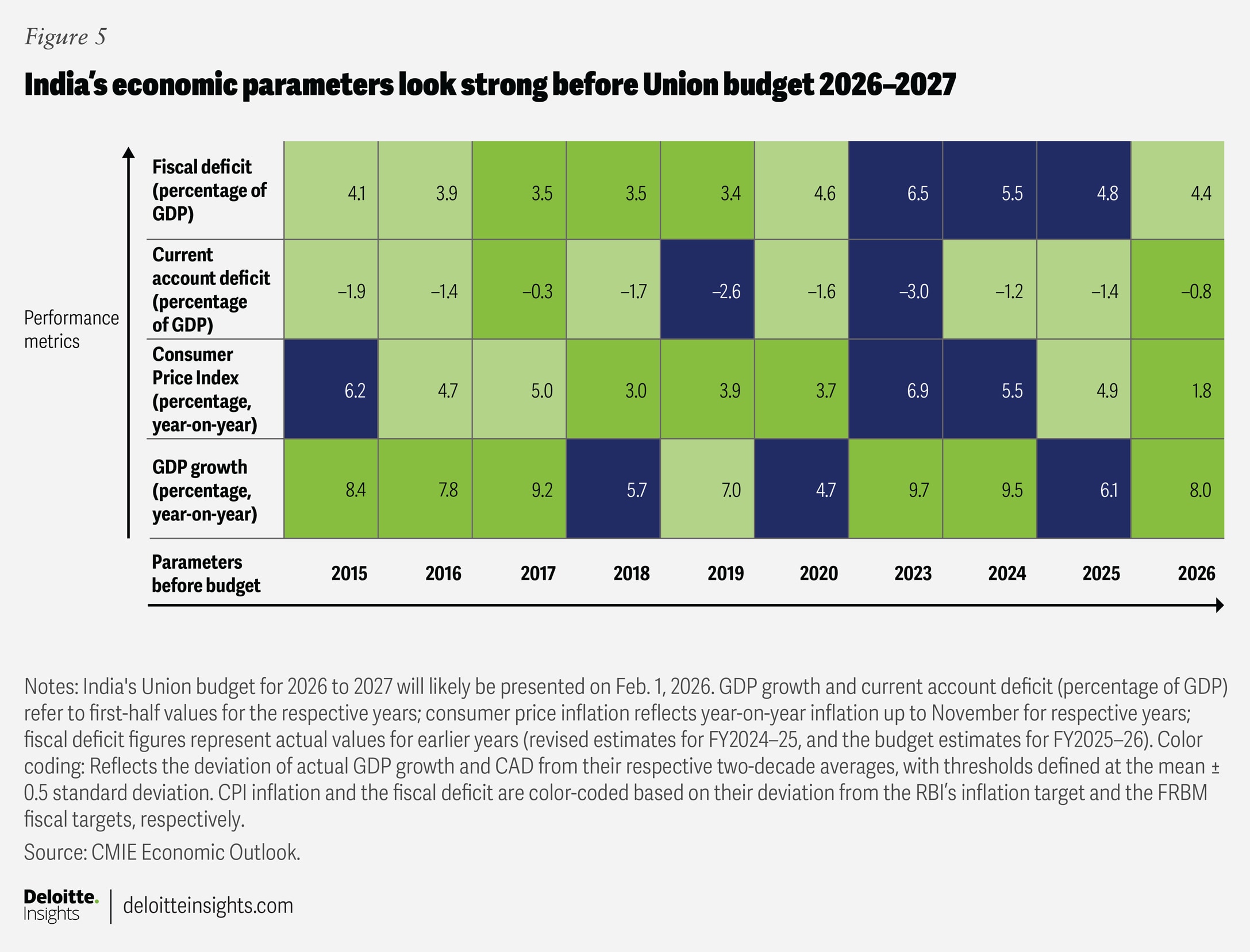

India stands at a pivotal moment. For the first time in a decade, a Union budget will be presented against the backdrop of robust economic indicators—strong GDP growth, controlled inflation, and resilient external balances (figure 5). Recent efforts to stimulate domestic demand amid global uncertainties have paid off, reinforcing India’s position among the fastest-growing major economies in the world.

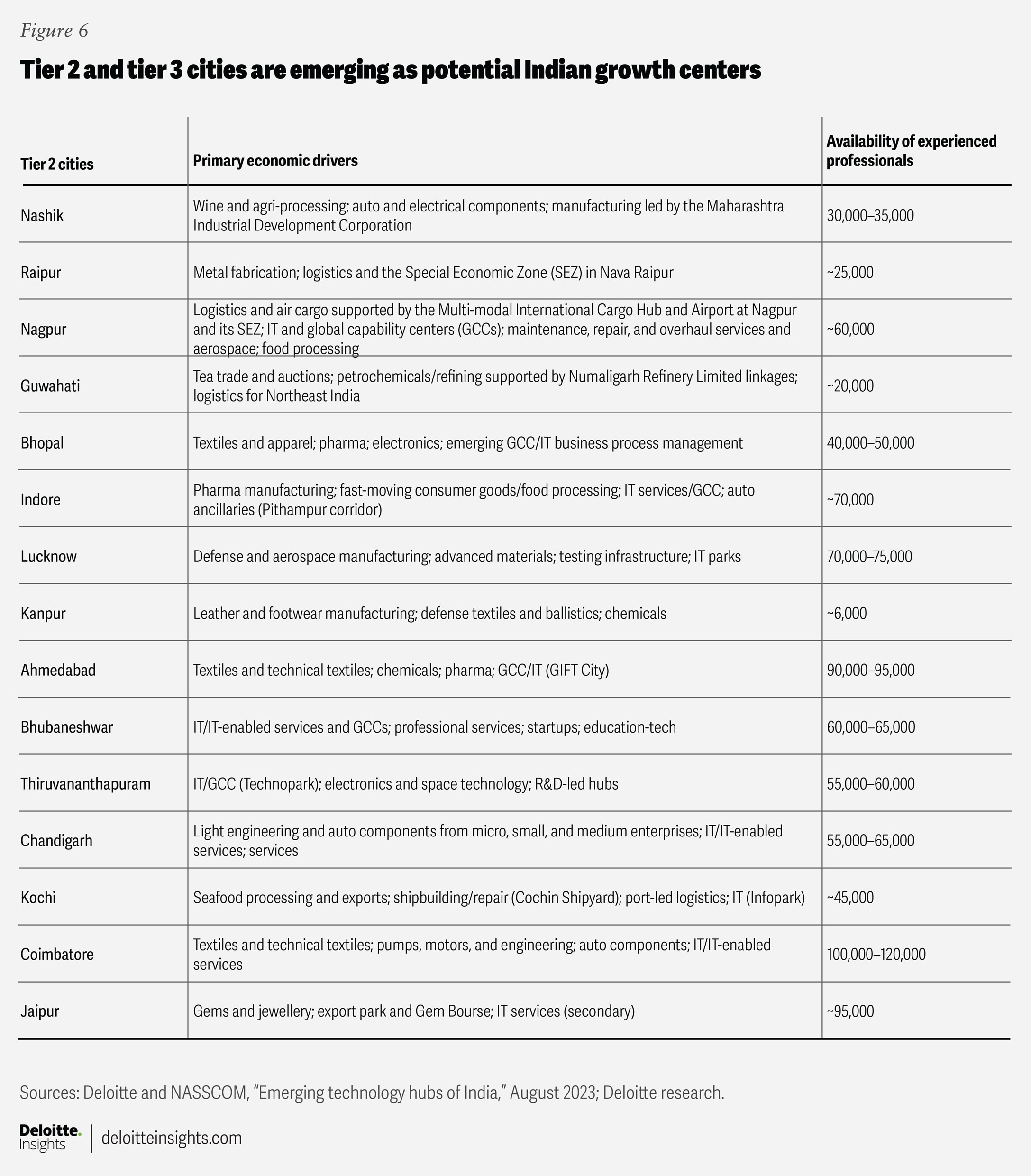

However, with limited demand-side policy levers remaining, the next phase of reforms must pivot toward supply-side improvements. This shift is essential to sustain momentum and build resilience against external shocks. Recently, the government hinted at a complete overhaul of customs to help improve the ease of doing business and reduce the cost of compliance and logistics. In addition, the budget may also focus on enhancing productivity, empowering MSMEs, and broad-basing growth in tier-2 and tier-3 cities.

Lately, these cities have been emerging as untapped engines of growth, increasingly attracting global capability centers (GCCs), manufacturing clusters, and startups. Cities such as Indore, Coimbatore, Lucknow, and Bhubaneswar exemplify this trend, benefiting from infrastructure upgrades and access to skilled labor. These urban centers hold immense potential to drive inclusive growth if supported by targeted interventions (figure 6).

In the Budget, the government may focus on building tier 2 and tier 3 infrastructure, which will entail:

- Industrial corridors and logistics parks: Accelerate the development of multimodal logistics hubs to reduce supply chain costs.

- Urban connectivity: Invest in regional airports, high-speed rail, and digital infrastructure to integrate tier 2 cities into national value chains.

- Sectoral clusters: Develop specialized clusters for textiles, auto components, and electronics in tier 2 cities, supported by common facilities and research and development centers.

- Public-private partnerships: Engage industry associations to cocreate infrastructure and training programs.

The Union budget may also support MSMEs to improve competitiveness by focusing on expanding export credit and concessional financing, strengthening credit guarantee schemes, simplifying compliance through digital platforms, and providing targeted incentives for sectors vulnerable to tariffs.

- Credit access: Expand collateral-free loans under schemes like CGTMSE and introduce sector-specific credit lines for export-oriented MSMEs. “Green‑channel” treatment in banks for compliant MSMEs should be promoted.

- Digital lending platforms: Promote “fintech” partnerships to enable faster, data-driven credit assessments for small businesses; expand TReDS interoperability and incentivize anchor‑led onboarding of supplier MSMEs.

- Strengthening MSMEs’ last-mile capacity: Improve accounting practices and digital platforms, and ensure optimum AI use in service delivery and production (including quality control, demand forecasting, and pricing).

For details, refer to Deloitte India’s “Budget expectations 2026.”

Key assumptions for Deloitte’s projections

GDP forecasts are based on the current national accounts series (2011–12). This ensures consistency and comparability, given the availability of historical data.

The next GDP data release is likely to incorporate a base year revision from 2011–12 to 2022–23, along with other methodological changes. These revisions could alter historical GDP series and growth rates. As a result, our projected growth numbers may change after considering the revised series.

Deloitte’s assumptions can be grouped into two scenario buckets: “optimistic” and “pessimistic,” with the former being more likely.

Optimistic scenario

India and the United States finalize a trade deal by the end of 2025, improving business sentiment. Tax exemptions, GST reforms, and easy monetary policy help boost consumer spending and investments.

The other assumptions are:

- The US Federal Reserve cuts policy rates as the US economy moderates.

- Various trade deals worldwide, bringing certainty to global trade.

- Crude oil prices remain range-bound (Brent prices at around US$65 to US$70 per barrel) due to balanced demand from emerging economies, heightened global uncertainty, and an increased supply of crude oil from the United States.

- The INR remains steady against the dollar at around 90 per dollar, helping India offset the impact of higher US tariffs on its goods exports.

Pessimistic scenario

Trade-related uncertainty continues, and US tariffs on Indian exports remain at 50% for this fiscal year and most of the next year. Exports decline fast, while shocks to supply chains impact costs and production. Regions with ongoing conflicts face prolonged economic uncertainty. As a result of political and policy changes, the United States and Europe enter recessionary phases, and investment and trade scenarios worsen. China’s economy slows, and supply disruptions cause high inflation. Monetary policy remains tight in both the West and India.