Latin America economic outlook 2025

Latin American economies are striving to improve their growth rates in a volatile landscape characterized by tensions between their primary trading partners

Daniel Zaga

Federico Daniel Di Yenno

Martin Pallotti

Nicolás Barone González

Daniel Gonzalez Sesmas

The economic landscape of Latin America is significantly influenced by the relationship between its two major trading partners: the United States and China. In this context, analyzing the region’s position within the geopolitical tensions between these partners is crucial to understanding its future economic activity and dynamics.

US-China relations have a long-standing history, shaped by geopolitical, economic, and military divergences, often leading to fluctuations in their bilateral ties. In recent times, the two countries have faced off on multiple issues, including tariff and nontariff trade policies.

Nonetheless, significant agreements have emerged, notably, China’s bid to stop seeking benefits from the World Trade Organization, which are aimed at boosting developing nations—a position backed by the United States.1 Moreover, China is the largest external holder of US debt, and the United States is a major consumer of Chinese goods, reflecting the importance of this relationship.

However, diplomatic ties have been strained in recent years, especially since 2018, when the United States imposed tariffs on several Chinese imports, which have been maintained through different presidential terms. Recently, the United States has started a new cycle of tariff increases on China, with retaliation from the latter, intensifying tensions between them.2

Latin America is not only affected by these moves but also plays a strategic role within the geopolitical interests of both partners. This is seen in the considerable growth of China’s participation in the region, especially in South America.3 Through greater trade and investment in the region, as well as funding under favorable terms and bilateral agreements, China has pursued objectives like expanding its technology, including in Latin America’s space sector.4

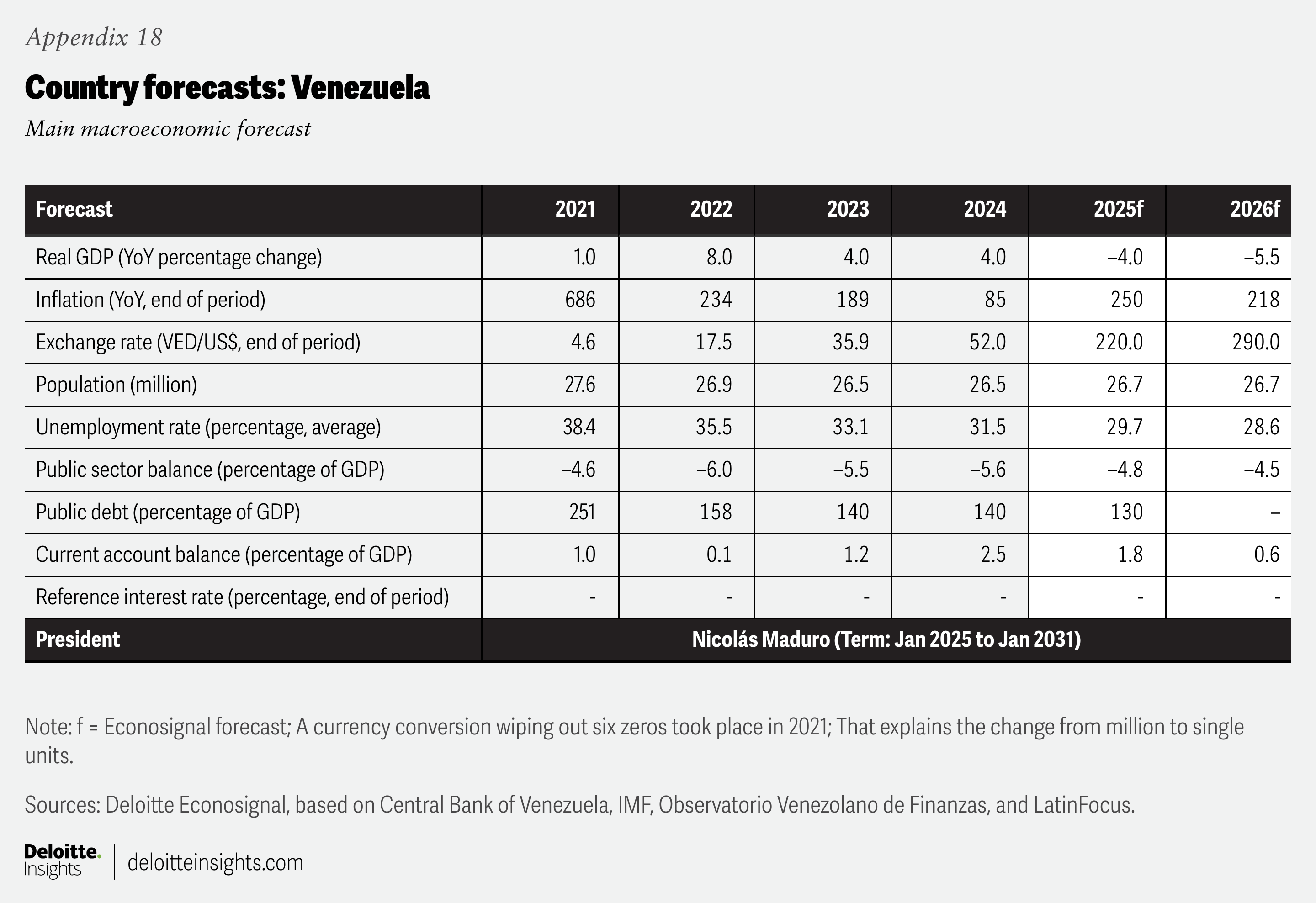

Between 2005 and 2024, China’s share of Latin American exports increased from 3% to 13%,5 while the US share declined from 50% to 44%.6 Although China accounts for a smaller overall volume, it has become the primary export destination for several countries in the region, including Brazil, Chile, and Peru (figure 1).

While China has expanded its presence in the region, the United States has taken a different approach—imposing sanctions and tariffs, and signing trade agreements to improve its trade balance, particularly with Mexico and Central America.

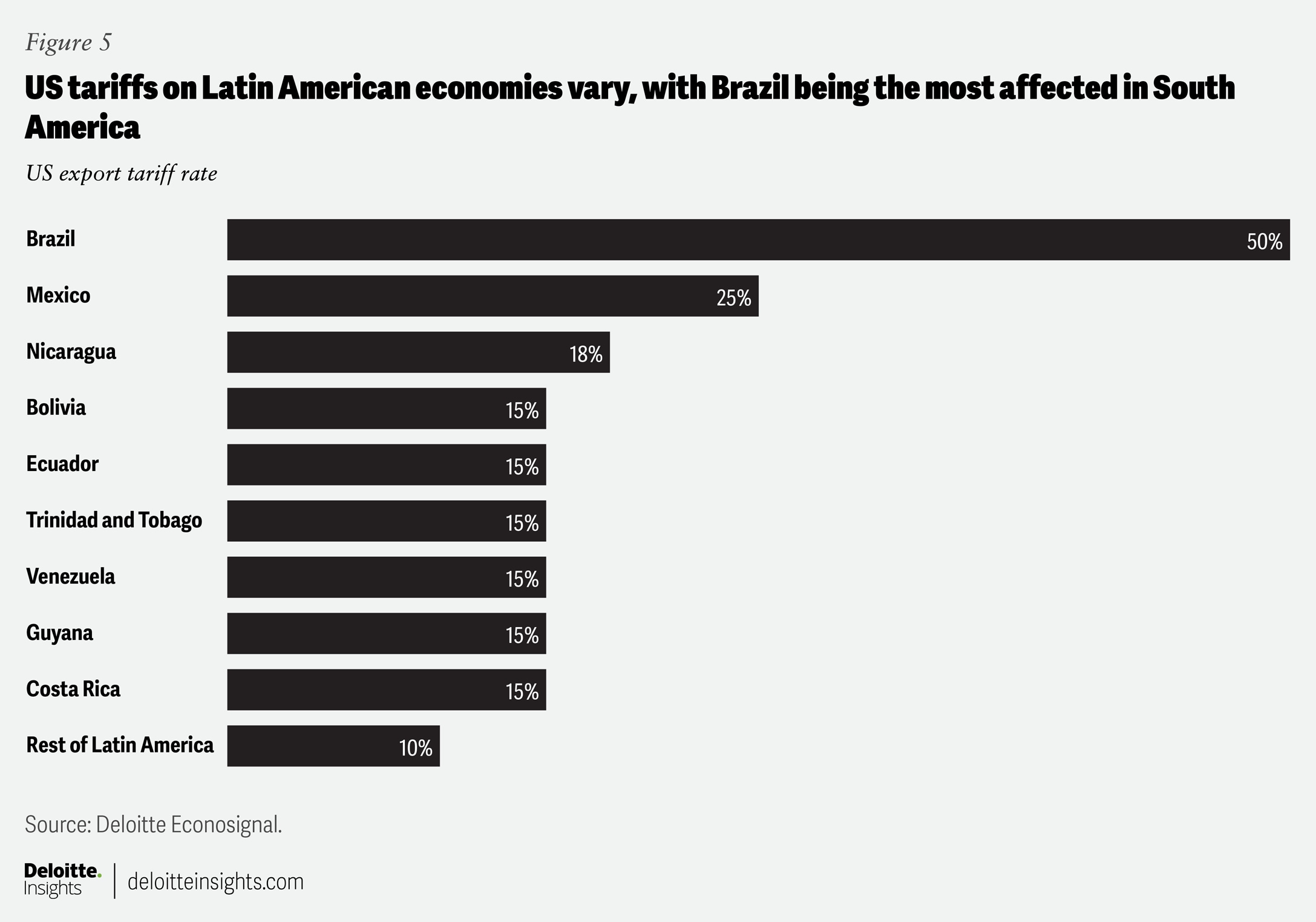

A recent example of such trade-related measures came on April 2, when the United States announced new tariffs on several trading partners in the region.7 These actions are part of broader efforts to address trade imbalances and strategic concerns. Among the most affected are Brazil and Venezuela, with tariffs of 50% and 15%, respectively, while most of the rest received a 10% rate.8

Tariffs will drive both direct and indirect effects on Latin America, as US-China trade tensions open up access to newer markets, increase global trade volatility, and reinforce the need to diversify exports to mitigate external shocks. The 2025 Latin America economic outlook explores the region’s economic ties with its biggest trade partners and estimates the impact of tariffs on regional growth.

Latin American relations with China and the United States

China and the United States are key markets for Latin American economies, and their relationships have developed through various channels, including trade, foreign direct investment, access to credit, and project funding.

Trade agreements have played a central role in shaping these ties. Notable examples include the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement and the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement, which involves Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and the Dominican Republic.

Likewise, China has advanced its Belt and Road Initiative, offering infrastructure financing and investment in exchange for access to natural resources and raw materials. This initiative has been endorsed by 21 Latin American countries.

Meanwhile, US efforts to expand trade agreements, particularly with South American nations, have been met with limited success.

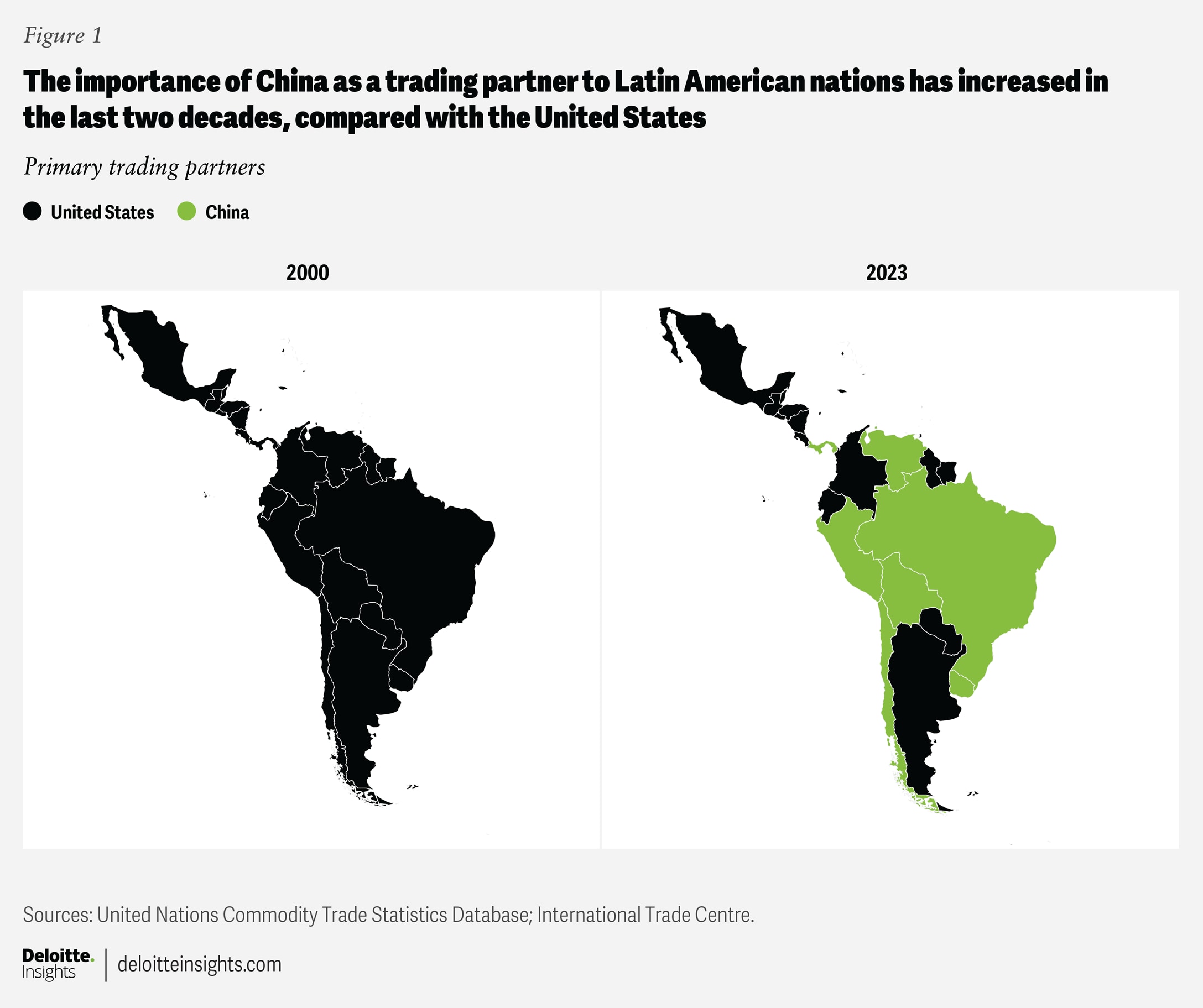

China’s strong economic growth has deepened its trade relations with Latin America, driving expansion in regional exports like agricultural goods and raw materials, which has contributed to the economic growth of several countries in the region, especially between 2000 and 2010. The correlation between Chinese growth and that of regional economies is strong (figure 2), especially during this period:9 China experienced growth of around 8%, while the Southern Cone—countries that are China’s main suppliers of primary products like soy, beef, and copper—saw elevated growth as well.

This is linked to China’s significant growth and increased demand for goods, which has led to higher export volumes and prices for important Latin American exports. Nevertheless, the Chinese economy has recently shown signs of slower growth—around 5%.10

On one hand, this could lower demand from China and lower prices for the goods it imports. On the other hand, the Chinese population now enjoys higher living standards,11which could present an opportunity to introduce higher value–added goods into the Chinese market.

However, there are risks as well, despite the opportunities in Latin America–China trade relations. Strong demand for primary products has led countries to focus their efforts and investments on exporting these products, eroding the diversification of their productive structures. The interference of Chinese manufacturing in Latin American and US markets also entails greater competition for countries in the region (such as Mexico and Central America), as they also rely on low-cost production as an advantage, putting them in direct competition with China on pricing.

Trade

In recent years, China has considerably increased trade with Latin America. Between 2000 and 2023, total trade (exports plus imports) increased from US$8 billion to US$415 billion, with an average annual growth rate of 15.2%.12 For comparison, global trade grew by around 6% year on year since 1995, when the WTO was established.13

Thus, China gradually became the main trading partner for South American countries and the second-largest trading partner in Latin America, mainly due to its demand for primary products such as soybeans, copper, and oil (figure 3), with Brazil being one of China’s main suppliers of soybeans and oil.

In the case of the United States, total trade with Latin America stood at US$353 billion in 2000. By 2023, it reached US$936 billion, at an average annual growth rate of 4%.14

Unlike China, the products imported by the United States require greater manufacturing complexity, with Mexico and Central America being its main trading partners, exporting automobiles, medical equipment, and computers.

The greater complexity of the products demanded by the United States offers advantages compared to the primary goods demanded by China, since they concern industries that require more labor and have higher added value. In contrast, China’s demand is focused on sectors that are less labor-intensive and more sensitive to price volatility. However, due to high demand, they allow for higher inflows of foreign currency into the region’s economies.

Investment

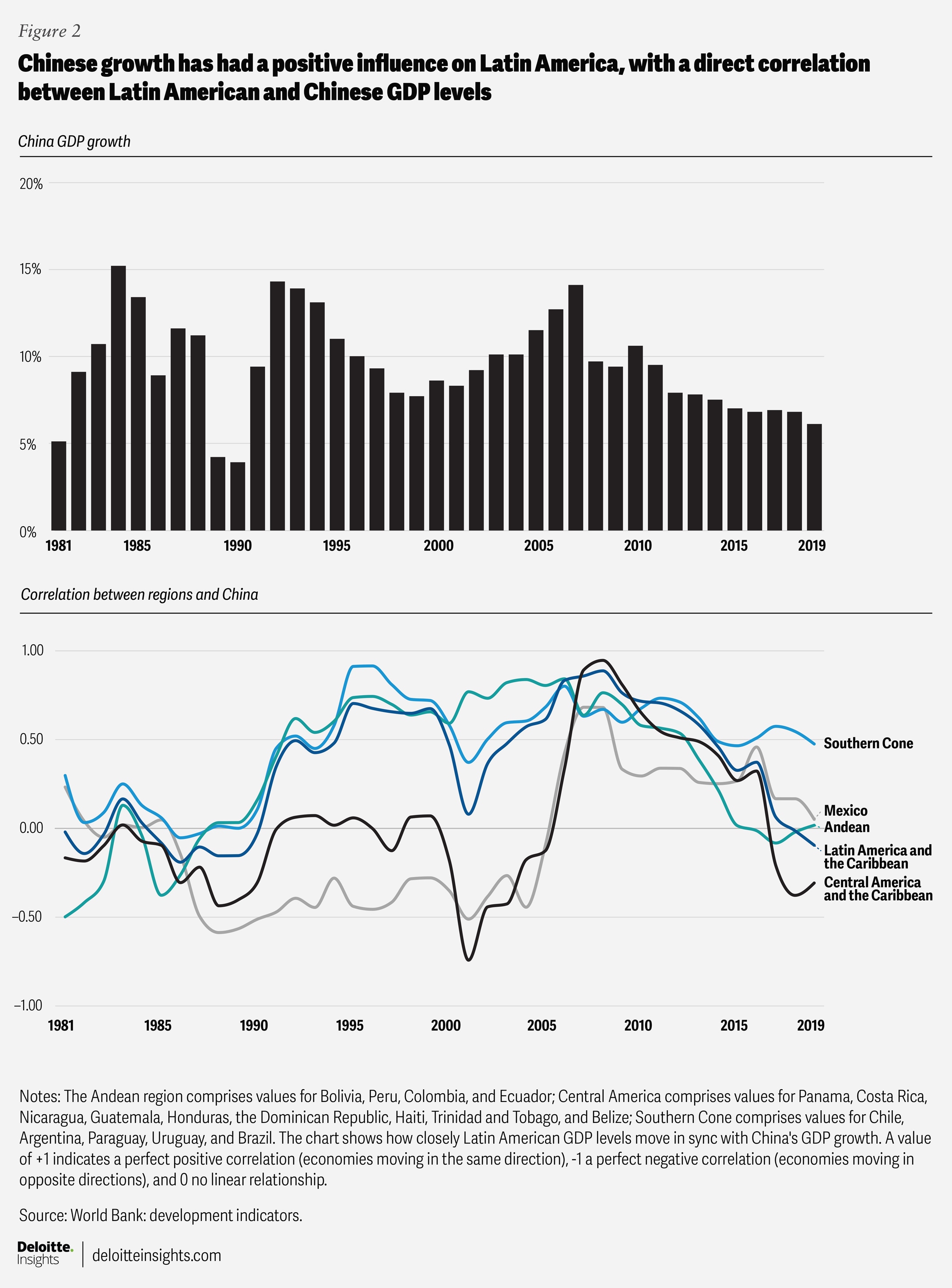

Capital from China has been an important source of investment in Latin America since the 20th century, showing sustained growth over time (figure 4). Between 2000 and 2004, Chinese investments reached US$2.8 billion, while between 2020 and 2024, they reached US$55.6 billion—a staggering increase of 1859%.15 During the latter period, Chinese investments were concentrated in Brazil (30.5%), Argentina (19.7%), and Peru (17.4%).16

Investments were primarily directed toward sectors critical to China’s economic development, such as energy and mining, which account for over 65% of Chinese investments in Latin America.17 Notable projects include the construction of a hydropower facility in Santa Cruz, Argentina; the second transmission line of the Belo Monte Dam in Brazil; and the Toromocho copper mine in Peru.

China has also channeled capital into local firms. The China National Petroleum Corporation holds a substantial share in Ecuador’s oil sector (55%),18 while companies like China State Grid Corporation and China Mobile have acquired assets in Brazil worth US$12.4 billion. Huawei’s 5G deployment in Curitiba stands out as a strategic milestone, although the specific investment amount has not been publicly disclosed.19

Despite China’s rapid growth, the United States remains the leading foreign investor in the region, sustaining relatively high levels of participation—at around 38% of total investment in 2024.20

Capital flows are primarily directed toward the energy, oil and gas, automotive, and telecommunications sectors. Key initiatives include oil extraction and hydrocarbon discoveries in Guyana; the construction of the Saguaro Energía LNG terminal and the Sierra Madre Gas Pipeline in Mexico; as well as automotive manufacturing plants established by General Motors and Tesla in the same country. The United States also leads in mergers and acquisitions, accounting for 34% of such activity in 2024.21

Debt and financing

As previously mentioned, one way China has strengthened its relationship with Latin American countries is by offering credit access with fewer requirements than those established by international organizations. Brazil and Ecuador have received loans from China worth around US$32.4 billion and US$11.8 billion,22 respectively—or 4.3% and 20% of their total external debt.

Bilateral swap line agreements are significant in this context, as they promote the use of the yuan for debt repayments, with Argentina being an example (see Argentina’s yuan-denominated transactions with China).23

Argentina’s yuan-denominated transactions with China

In 2014, the Central Bank of Argentina (BCRA) agreed to exchange local currencies with the People’s Bank of China (PBC) for US$11 billion. The agreement allowed the BCRA to request a maximum of 70 billion yuan from the PBC and, in return, deposit an equivalent amount in Argentine pesos, with a repayment period of up to 12 months. The agreement was expanded in 2015 to 130 billion yuan (US$18 billion), but a 2018 amendment stipulated that if the International Monetary Fund’s standby agreement with Argentina were suspended or canceled, the PBC could reject BCRA drawings.

Following a meeting between the presidents of the PBC and BCRA in January 2023, the activation of the currency exchange agreement was confirmed, and both nations committed to strengthening the use of the yuan in the Argentine exchange market. The agreement includes a special allocation of 35 billion yuan to offset transactions in the foreign exchange market. Once activated, this amount becomes part of Argentina’s external debt (2% of the country’s total). As a result, Argentina now conducts transactions with China almost exclusively in yuan.

The United States has played a more limited role in providing financing to countries in the region due to stricter requirements to access financing, such as the need for financed projects to comply with environmental standards.24

Recently, however, the United States negotiated a swap line with Argentina for US$20 billion, similar to the arrangement with Mexico during the Tequila Crisis, with the aim of helping Argentina meet its debt obligations. The reason behind this agreement lies in Argentina’s vulnerable exchange-rate situation, and its approval would provide a source of funding to help the country manage exchange-rate volatility and the declining demand for Argentine pesos—typical of a “bimonetary” economy during an election period.

Tariffs and trade war between China and the United States

Recently, the US administration has implemented a series of tariff policies on its trading partners and various productive sectors, aiming to reduce trade deficits with these countries and strengthen the American manufacturing industry.

Canada and Mexico, its two main trading partners, have faced tariff rates of 35% and 25%, respectively. For Mexico, tariffs have been imposed on goods beyond the scope of the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement, while tariffs on specific products such as steel, aluminum, and copper have reached 50%.25

A possible reason driving the tariffs on Mexico might be the intention to counter nearshoring—one of the strategies used by Chinese companies to introduce their products into US markets. Nearshoring allows foreign companies to establish operations in countries like Mexico to benefit from trade advantages with the United States, enabling them to export to the country at lower costs while bypassing trade measures imposed on their countries of origin.

Latin American countries have not been exempted, although the tariffs imposed differ across the region. Brazil and Venezuela are among the most affected, with tariffs of 50% and 15%, respectively, while most other countries face tariffs of around 10% on their exports to the United States (figure 5).

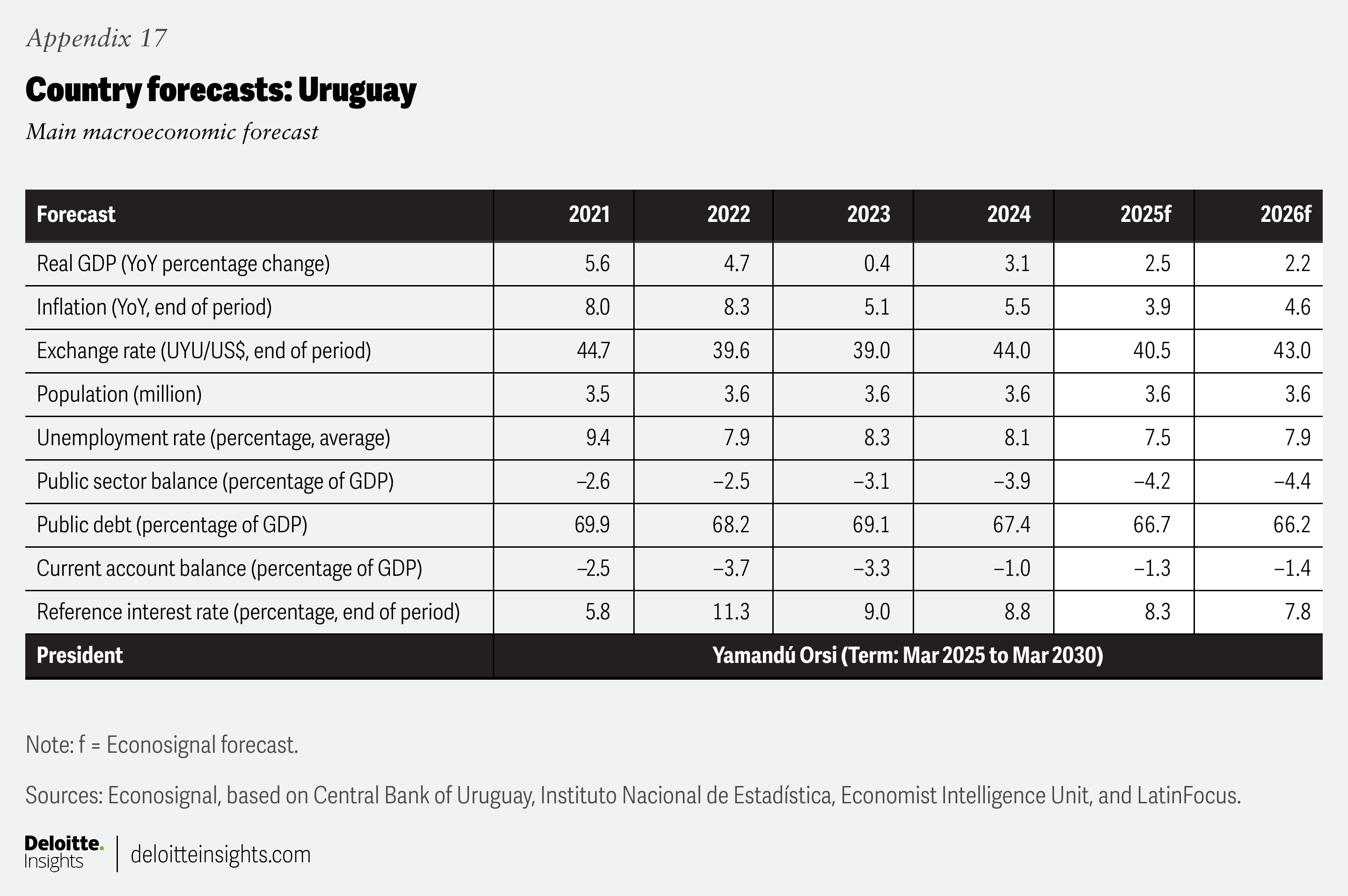

These tariffs can have both direct and indirect effects on countries through a possible diversification of markets and trade relationships within the region. For example, the tariff on Brazilian meat creates opportunities for Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay, as the higher prices of Brazilian products allow for increased competition in these markets. However, the diversification of Brazilian meat exports could generate greater competition for other countries, both in their domestic markets and abroad.

In addition, the possible economic effects may extend to other countries through their trade relationships. For example, a decline in demand in certain Brazilian markets could have important implications for Argentina, given that Brazil is its main export destination.

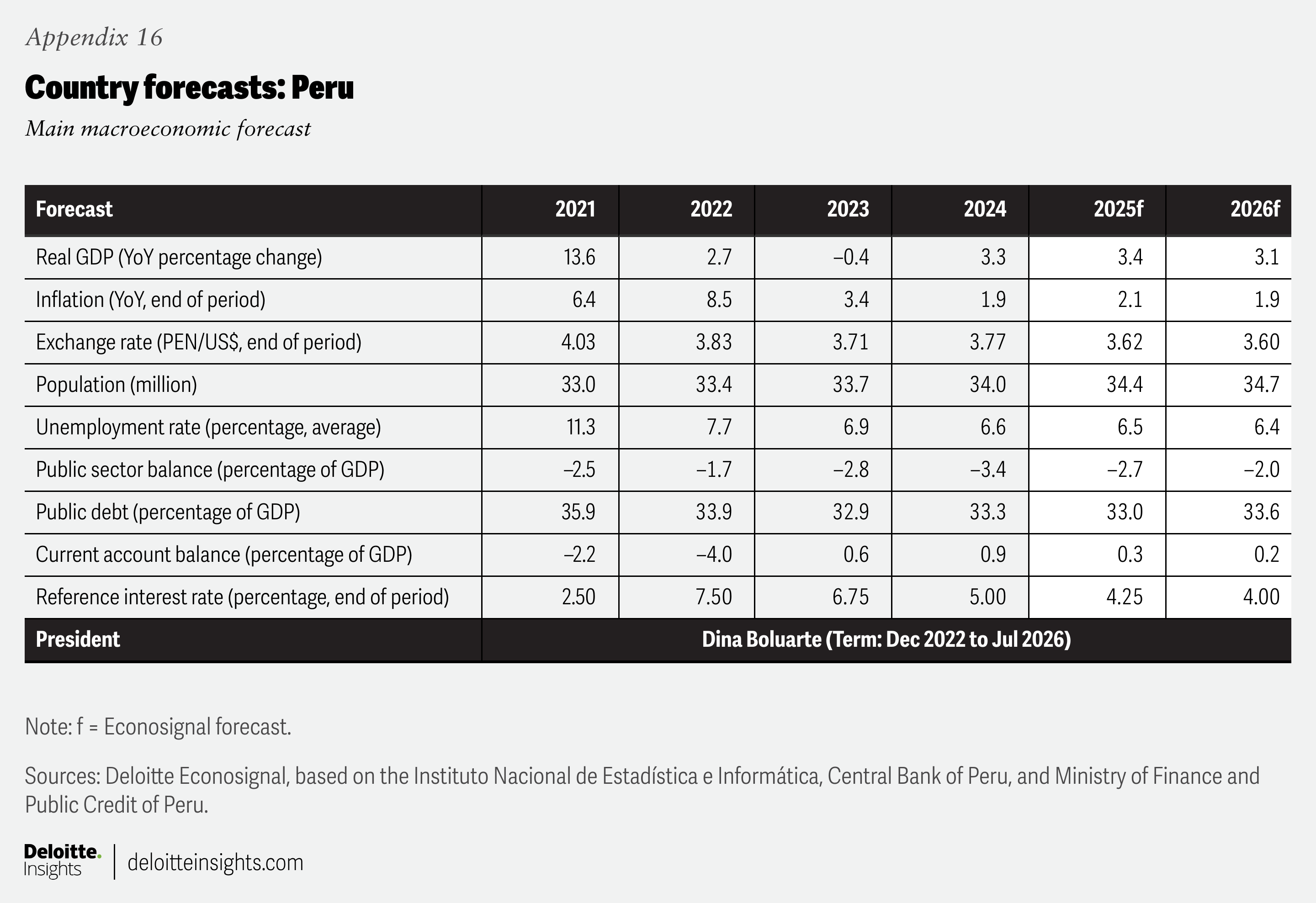

Tariffs in specific sectors also have important implications. Peru and Chile, despite facing 10% tariff rates, are affected by the tariffs imposed on copper, one of their main exports—with copper accounting for 18% and 5% of their total exports to the United States, respectively.

Commodity prices are another channel through which tariffs exert pressure, as uncertainty surrounding price volatility leads exporters to adopt precautionary behavior. In the case of oil, the price per barrel is around US$63—below the five-year average of US$74. Countries such as Argentina, Colombia, and Brazil—whose exports to China and the United States include oil—are experiencing a decline in export values due to current prices, and if prices remain low, investment in the sector may also decrease.

However, gold—one of the main products exported by Peru and Argentina to China—has seen price increases throughout the year due to the weakening of the US dollar and uncertainty surrounding the performance of the US economy.

The dynamics of the US exchange rate and economic performance will be important to monitor. A potential interest rate cut by the Federal Reserve, signs of economic weakening, and greater clarity on the final tariff framework could lead to changes in the exchange rate and, therefore, impact commodity prices and investment flows to Latin America.

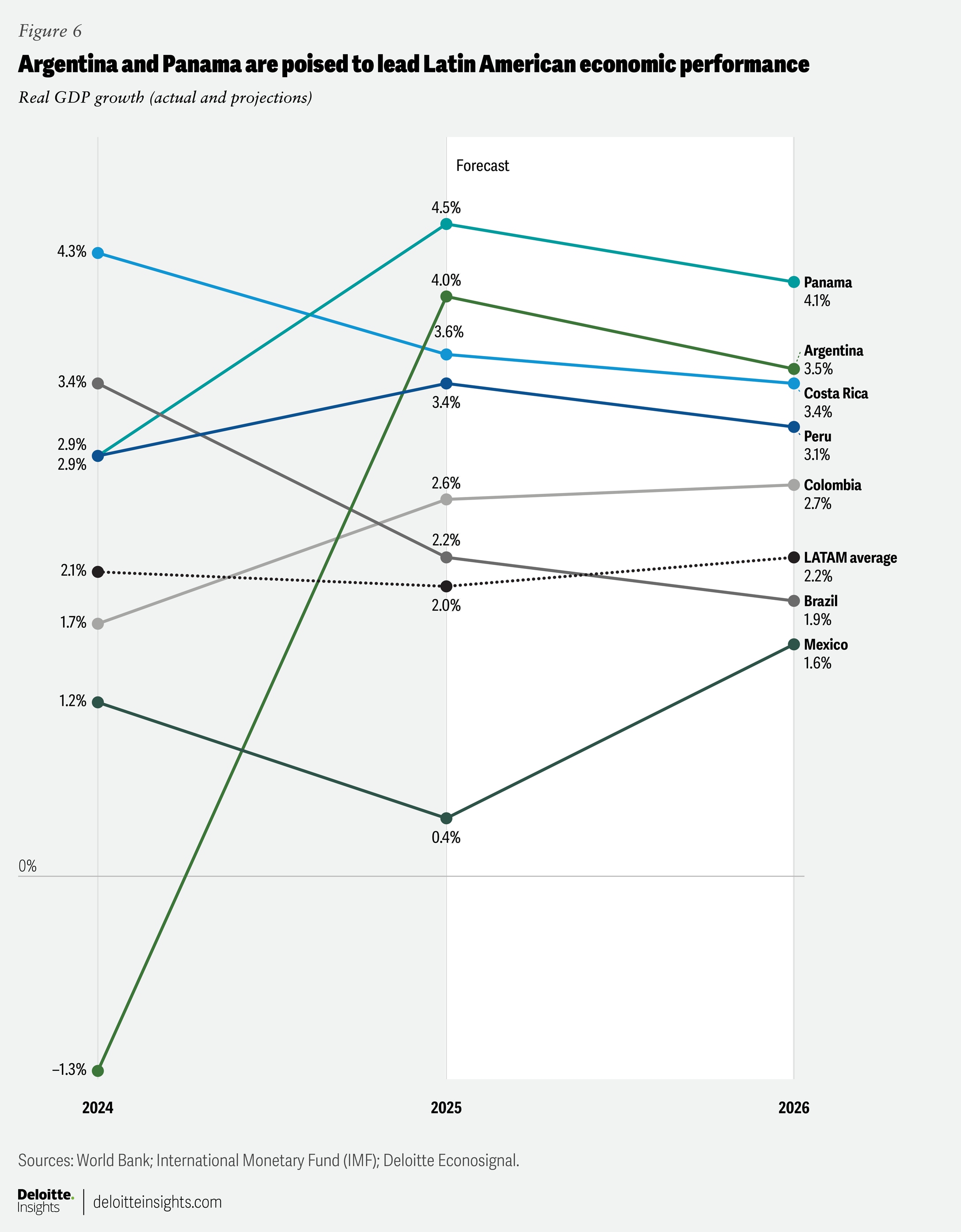

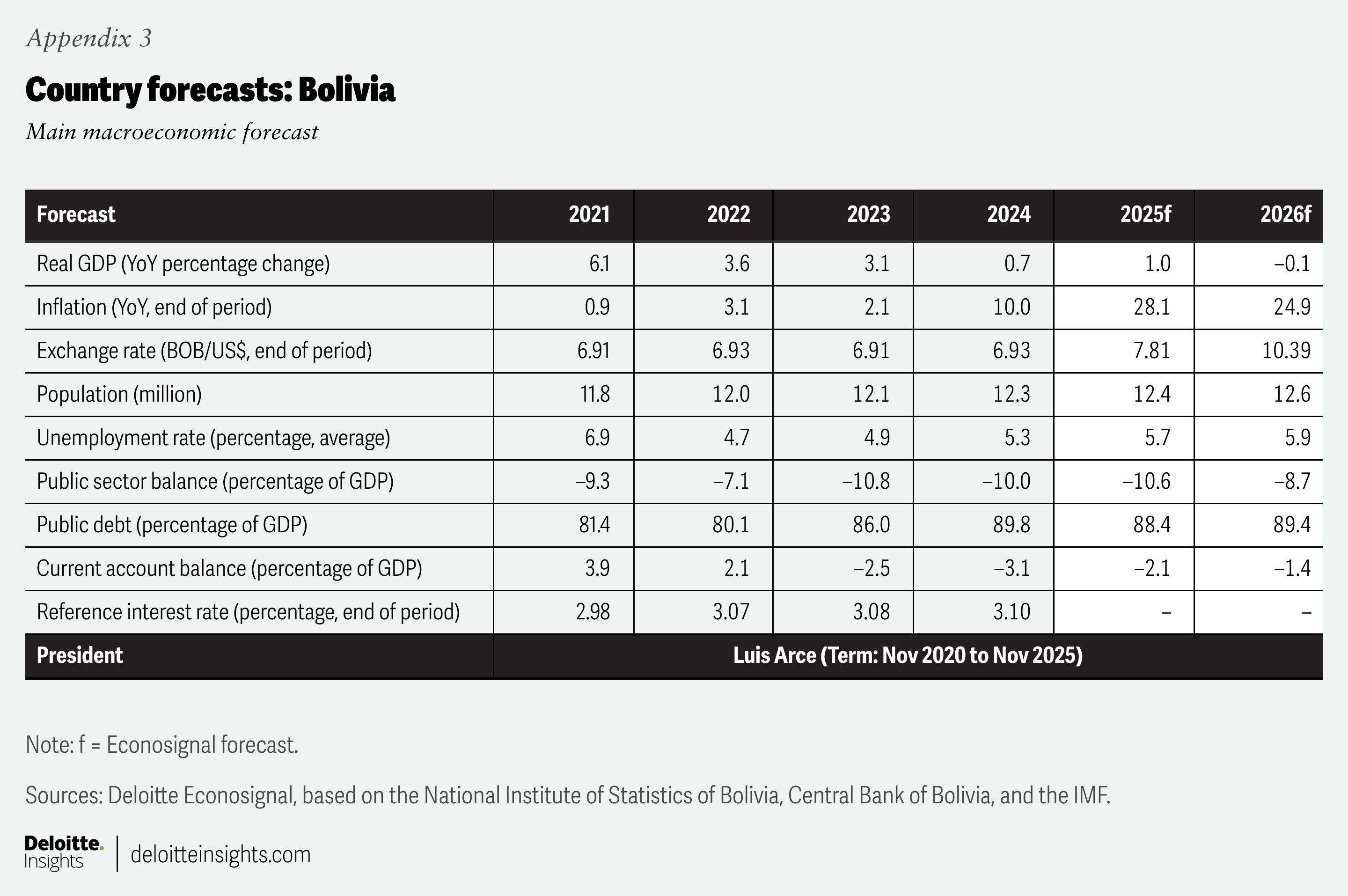

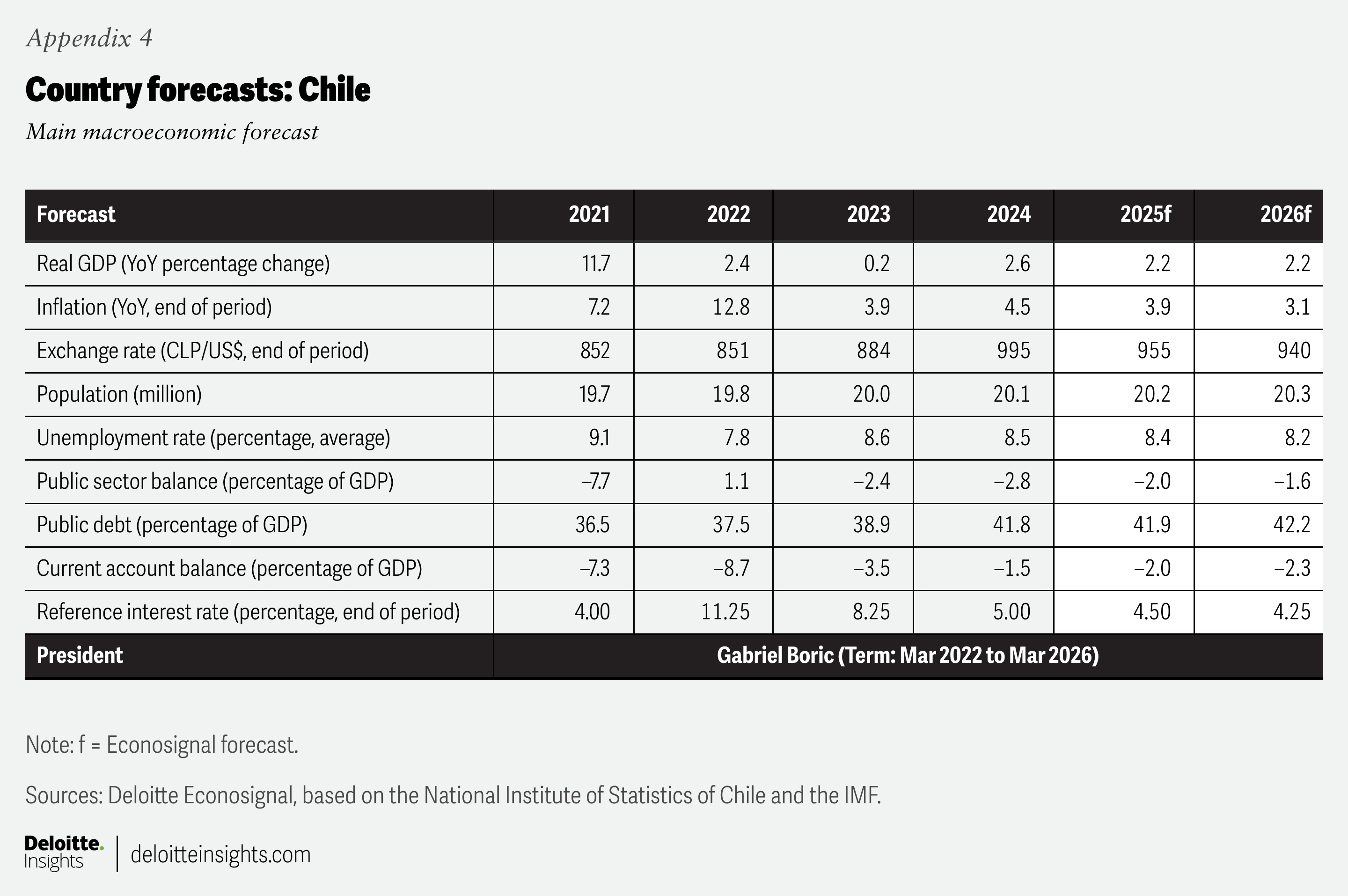

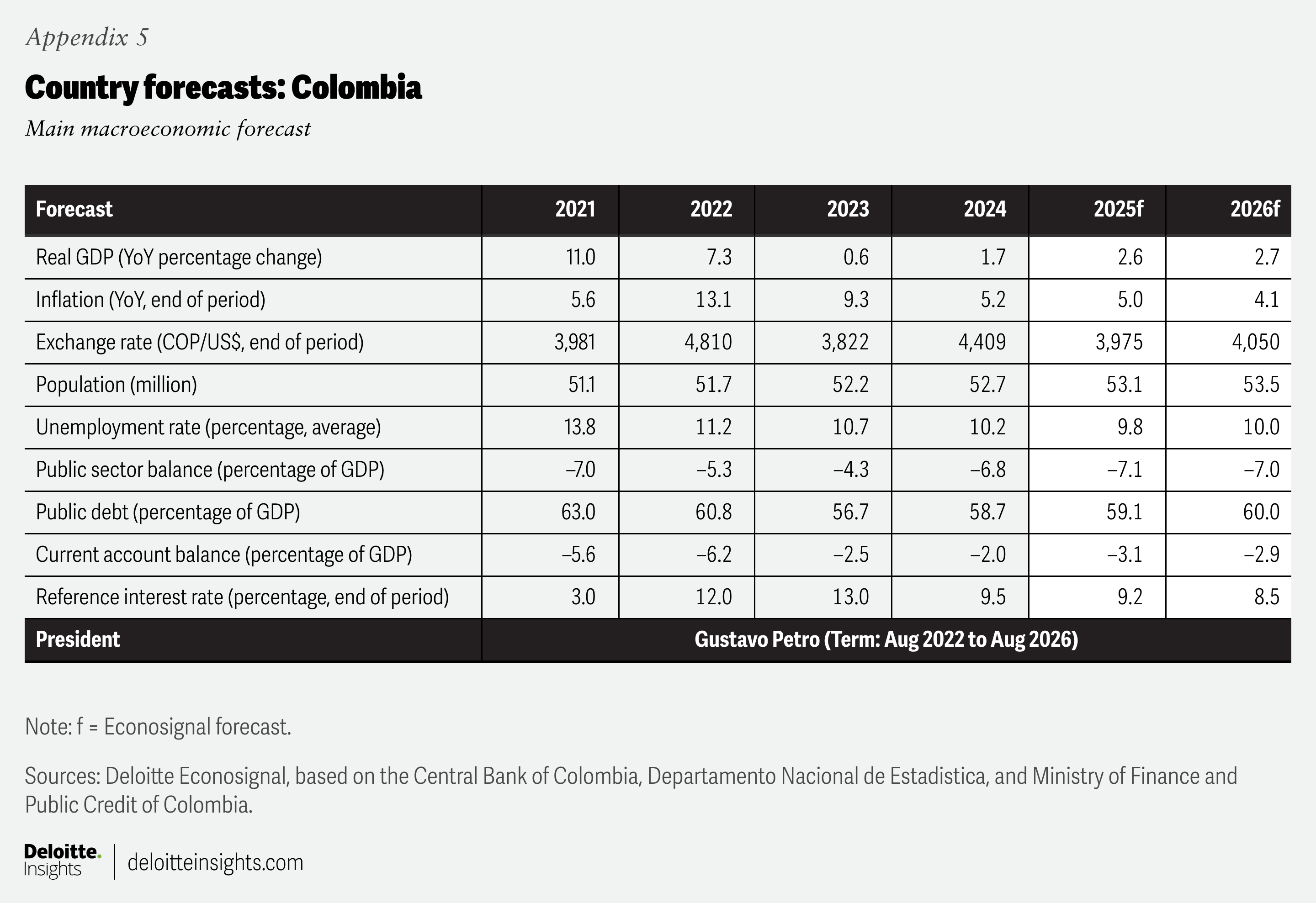

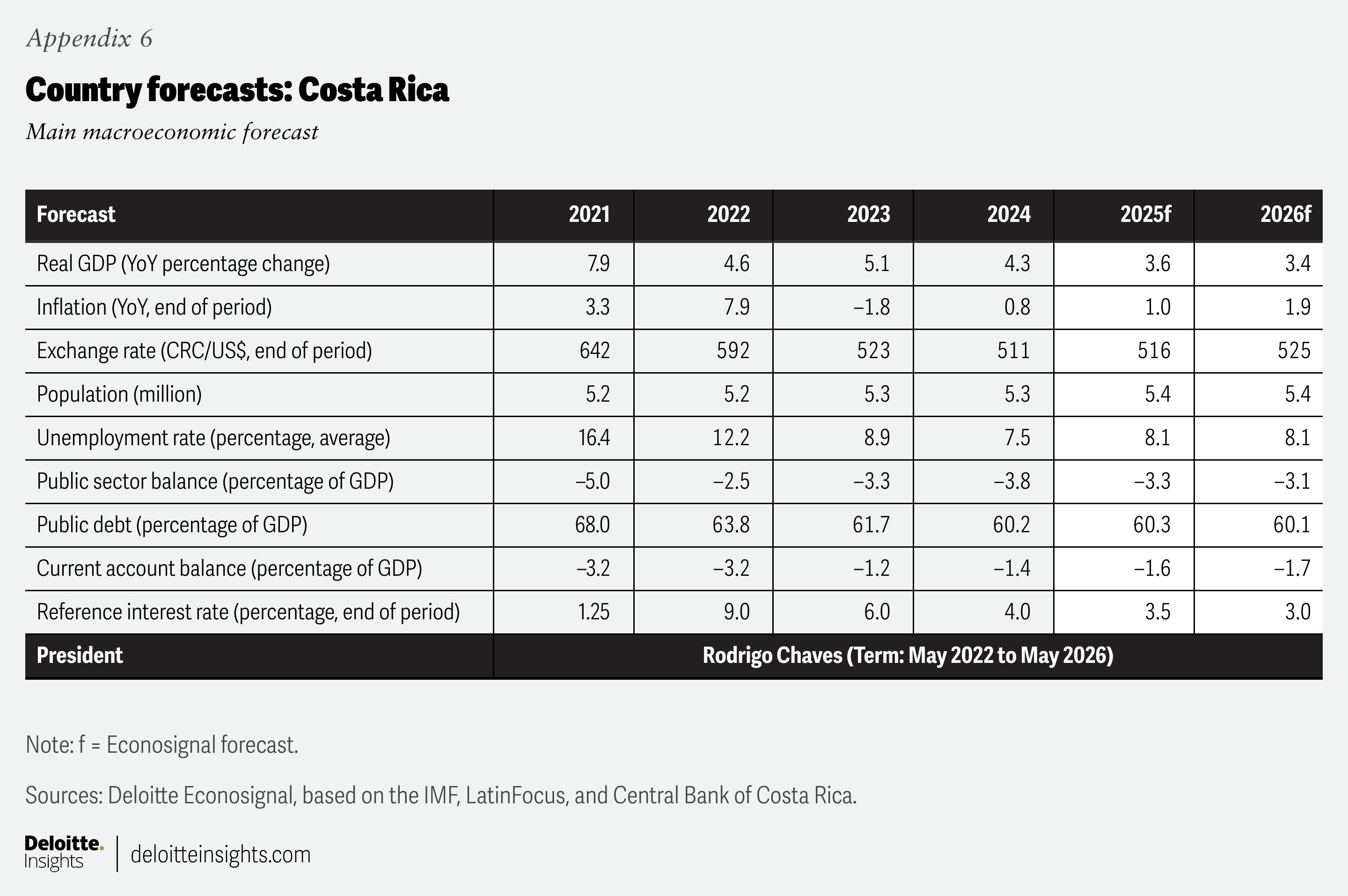

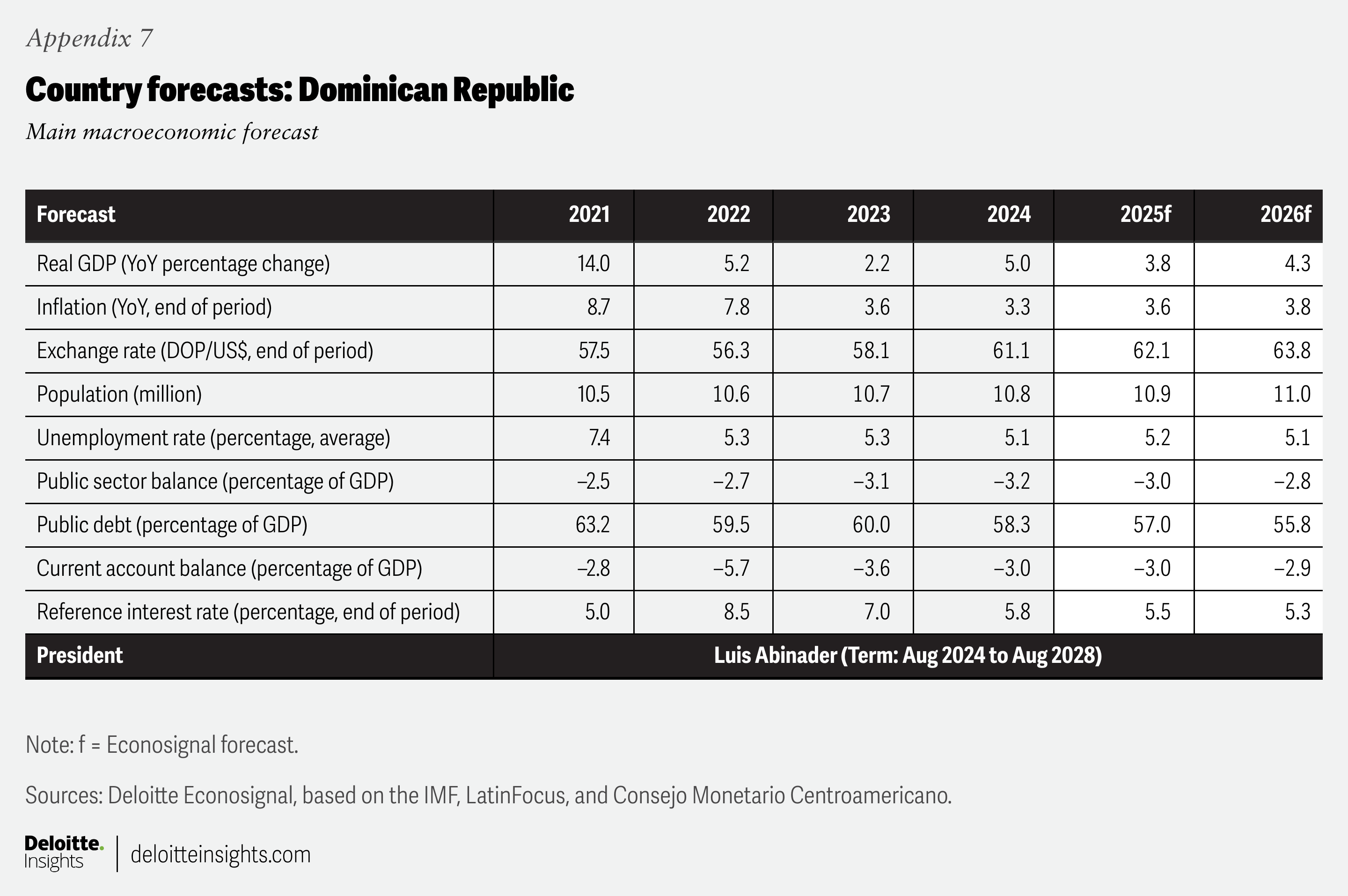

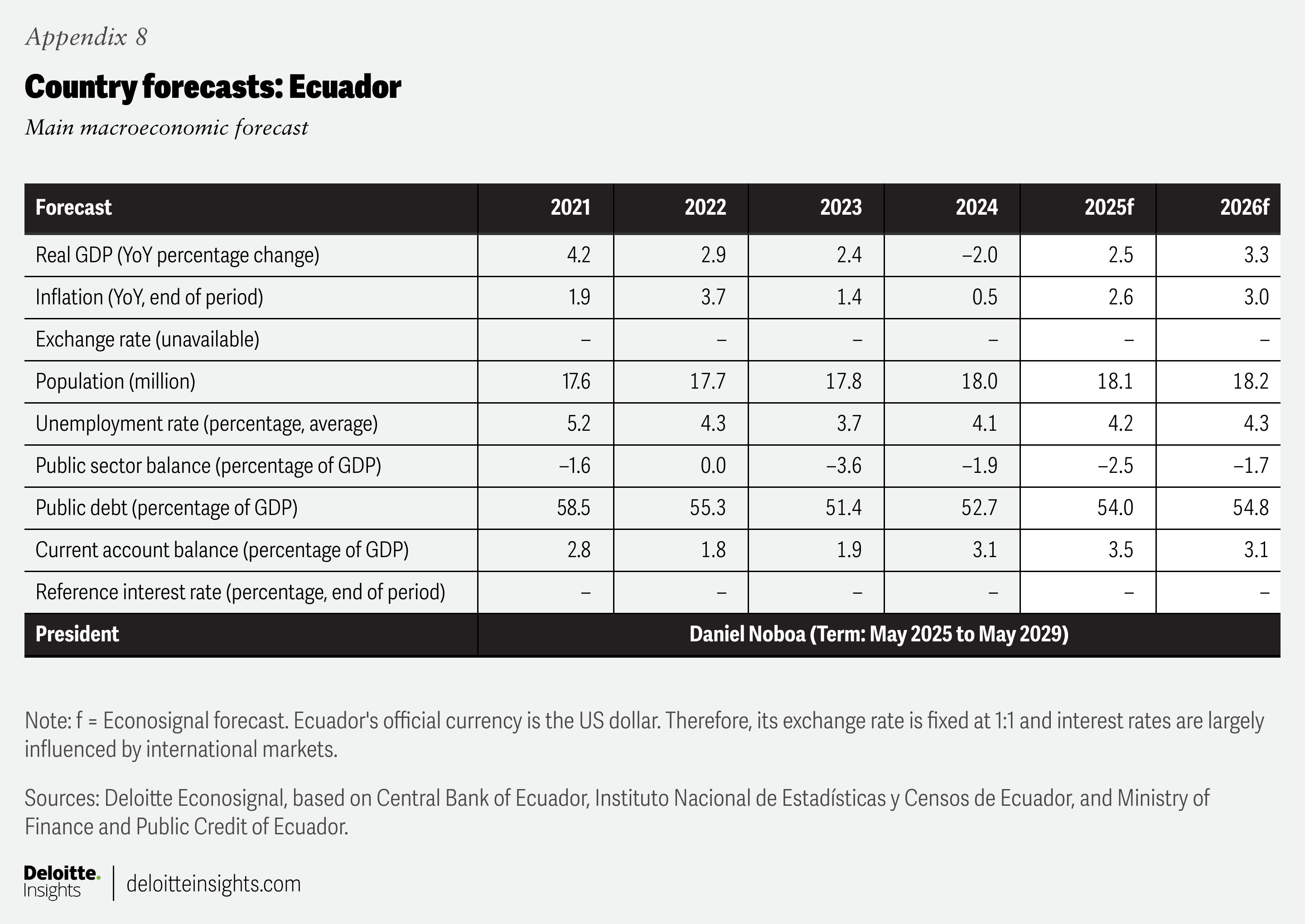

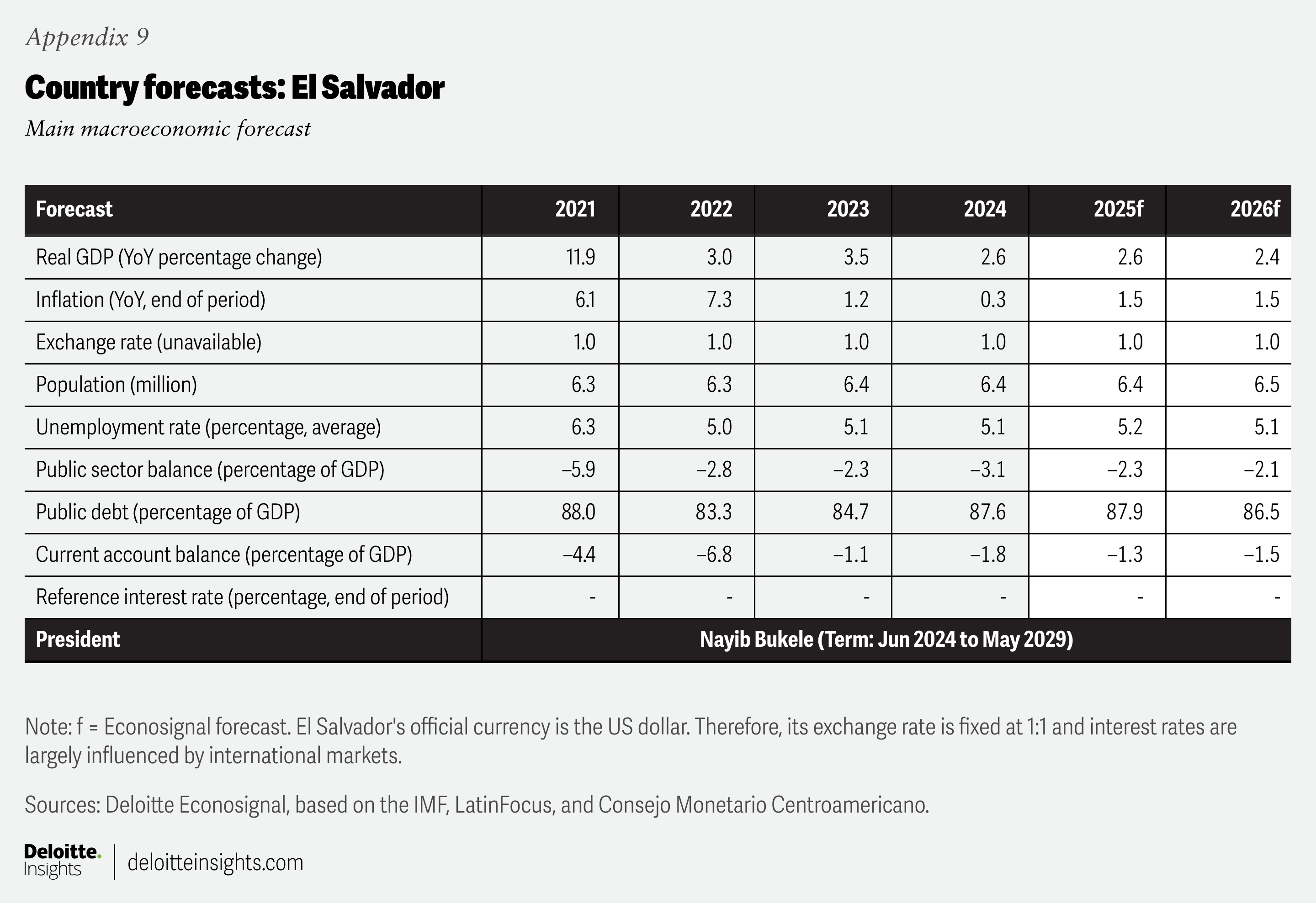

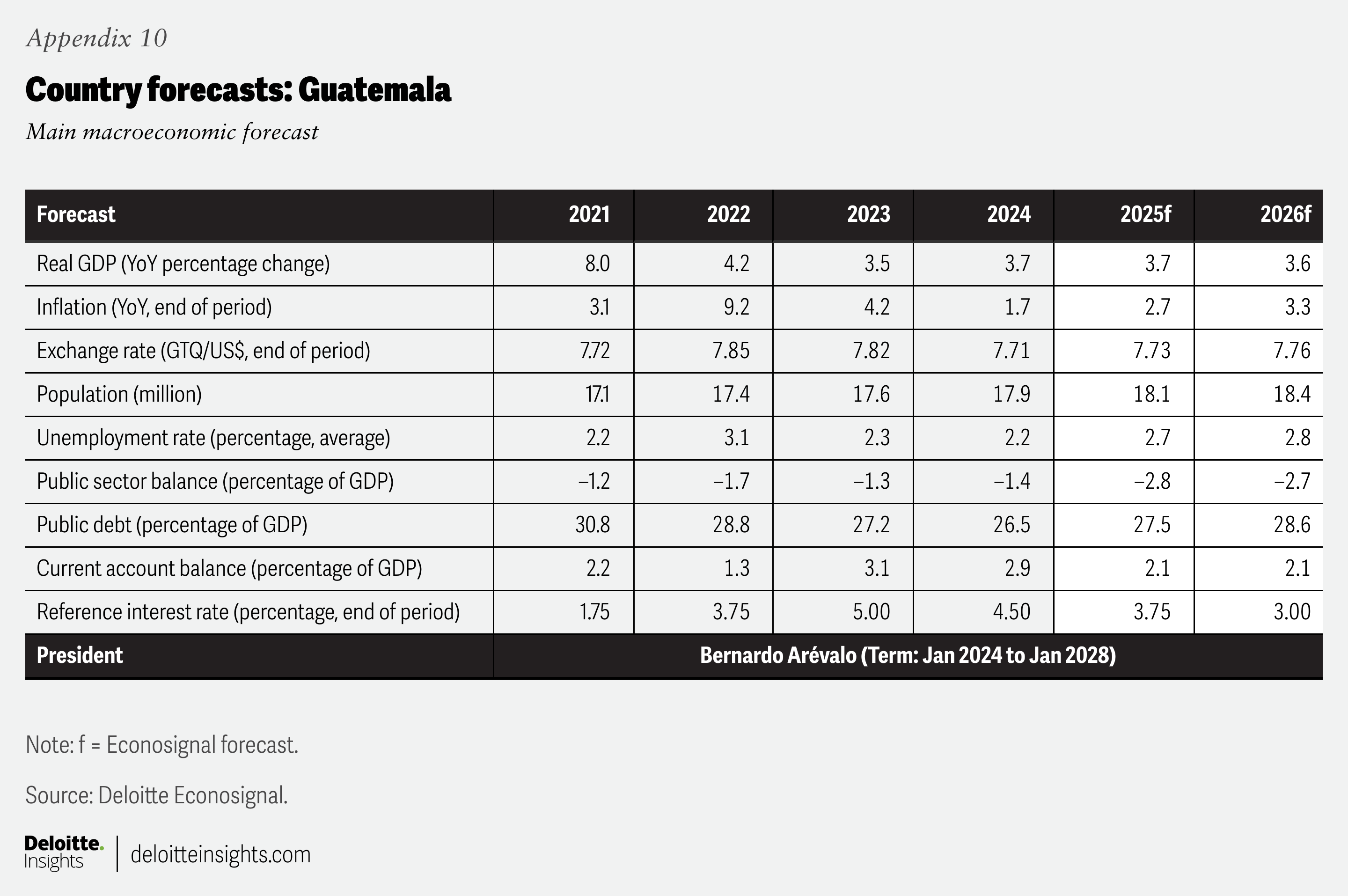

These tariffs impact regional economies at a time when low growth rates are expected (figure 6) (see appendix for 2025 and 2026 projections for selected economies).

Under this framework, monitoring US trade policy will continue to be imperative: Deloitte’s Econosignal team projects a possible and limited short-term effect, along with additional medium-term opportunities related to nearshoring, especially for Mexico and Costa Rica.

Tariffs could not only significantly affect Latin American countries but also affect geopolitical relationships with China—either through attempts to diversify their markets or through moves away from China to balance trade relations with the United States, as in Panama’s exit from the Belt and Road Initiative agreement with China.

Striking a balance will be key to Latin America’s economic future and prosperity

Latin America’s economic performance remains closely tied to its key trading partners—the United States and China—which are also major sources of investment and financing for the region’s economies.

While China has expanded its influence through trade, infrastructure investment, and financial cooperation, the United States continues to lead in foreign direct investment and remains a dominant commercial partner, particularly for Mexico and Central America, while also imposing tariffs on most countries in the region.

The imposition of US tariffs introduces both risks and opportunities for Latin American economies. These measures may disrupt trade flows and reduce commodity prices, affecting export revenues and investment. On the other hand, they may open new market opportunities for countries able to reposition themselves competitively. The region’s exposure to commodity cycles, limited diversification, and dependence on external demand underscore the need for structural reforms and export diversification strategies.

Looking ahead, Latin America’s growth prospects remain moderate and uneven across countries. The region must adapt to a more volatile global trade environment, balancing its relationships with both China and the United States while strengthening internal resilience. Monitoring the evolution of US trade policy, Chinese economic performance, and global commodity trends will be essential for anticipating future challenges and opportunities.

Appendix 1: Country forecasts

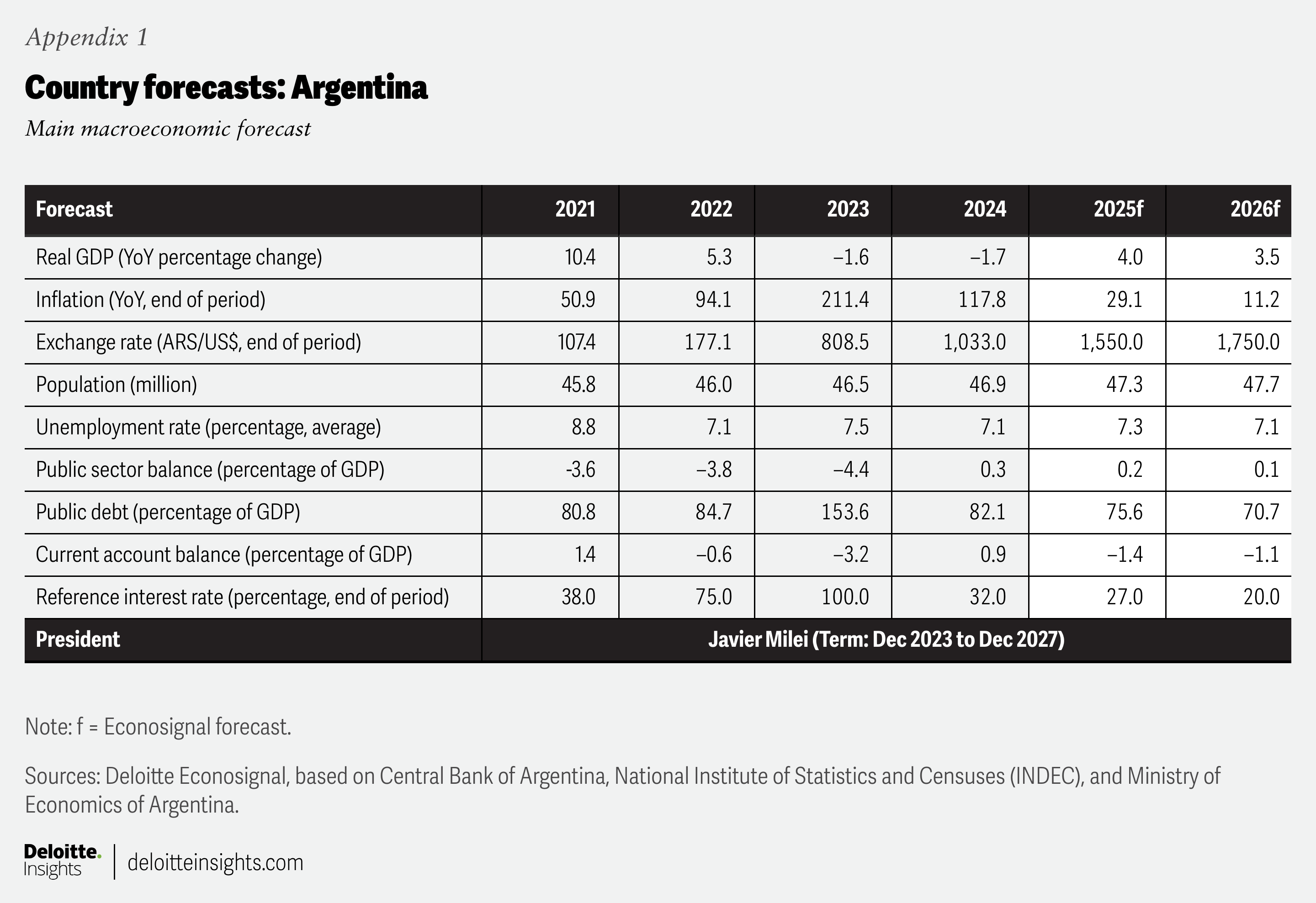

Argentina: Main macroeconomic forecast

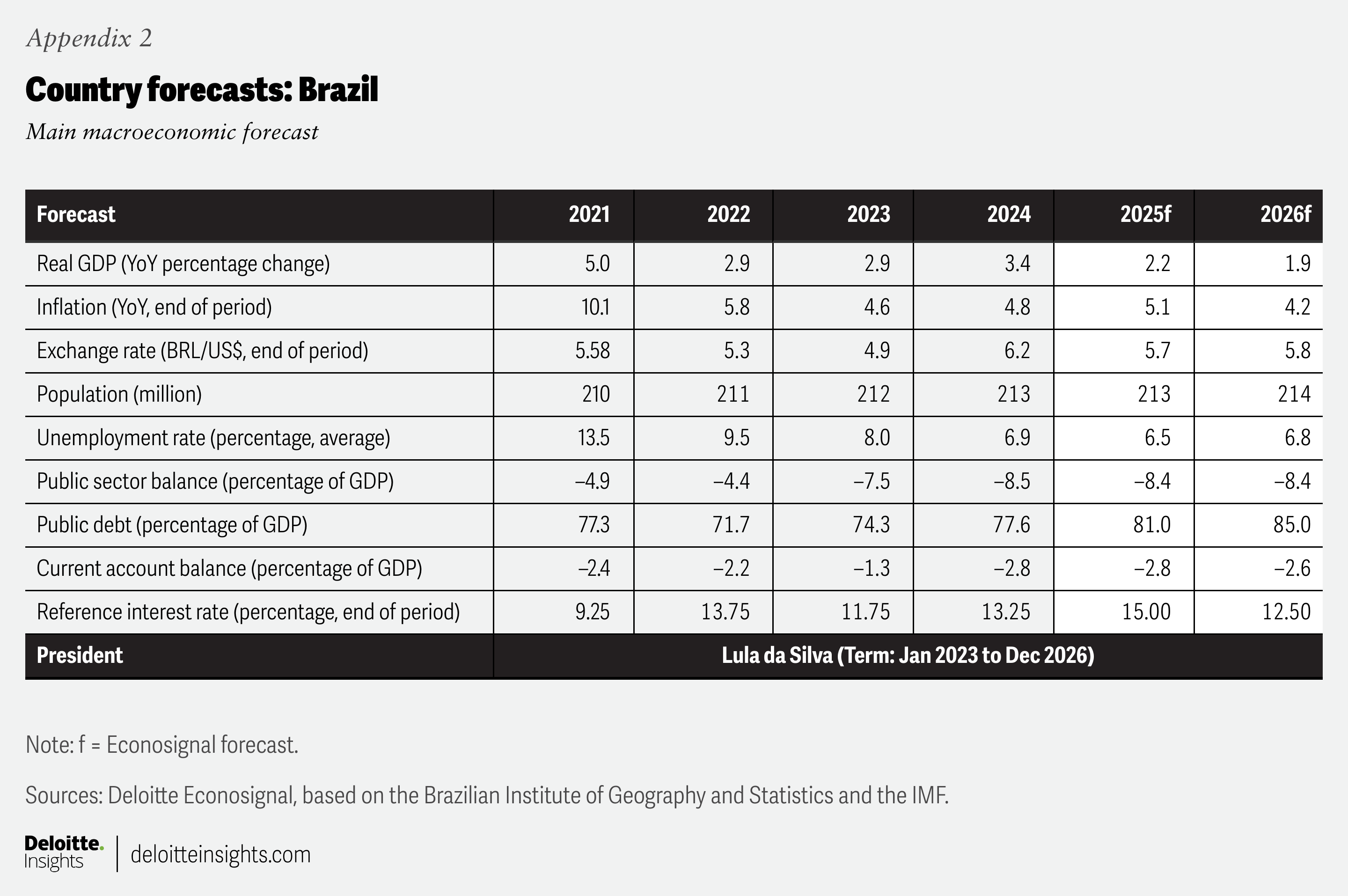

Brazil: Main macroeconomic forecast

Bolivia: Main macroeconomic forecast

Chile: Main macroeconomic forecast

Colombia: Main macroeconomic forecast

Costa Rica: Main macroeconomic forecast

Dominican Republic: Main macroeconomic forecast

Ecuador: Main macroeconomic forecast

El Salvador: Main macroeconomic forecast

Guatemala: Main macroeconomic forecast

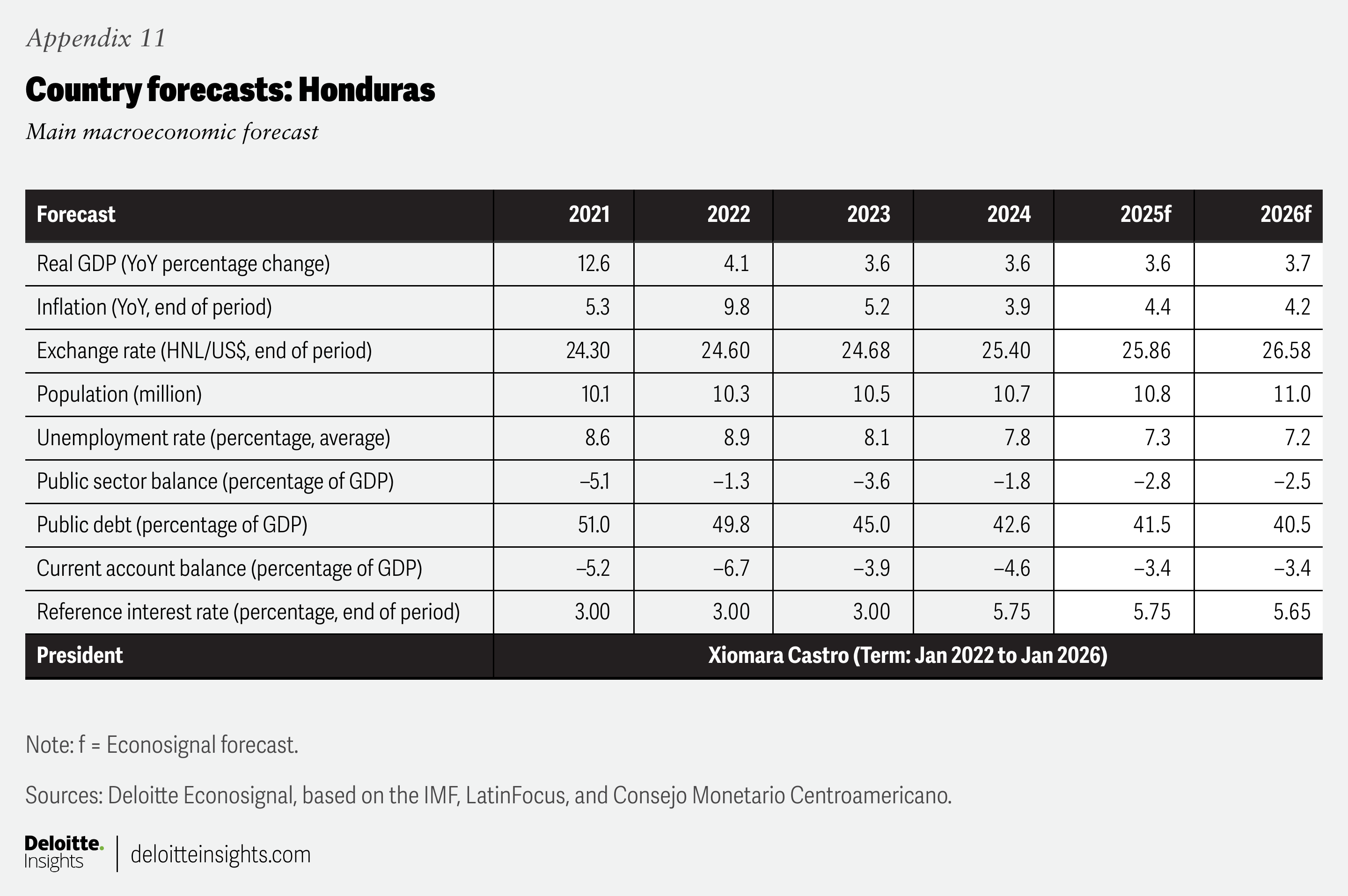

Honduras: Main macroeconomic forecast

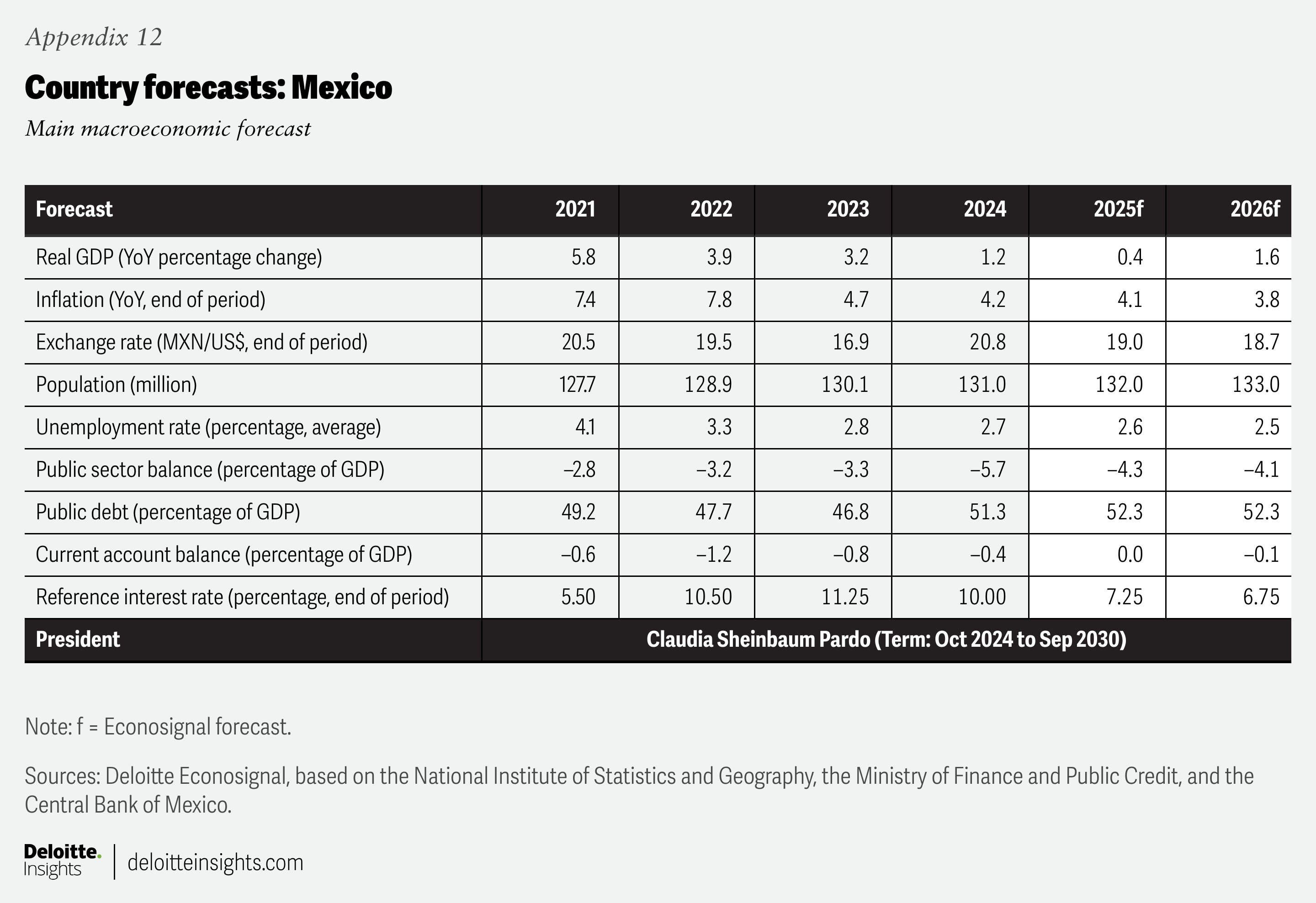

Mexico: Main macroeconomic forecast

Nicaragua: Main macroeconomic forecast

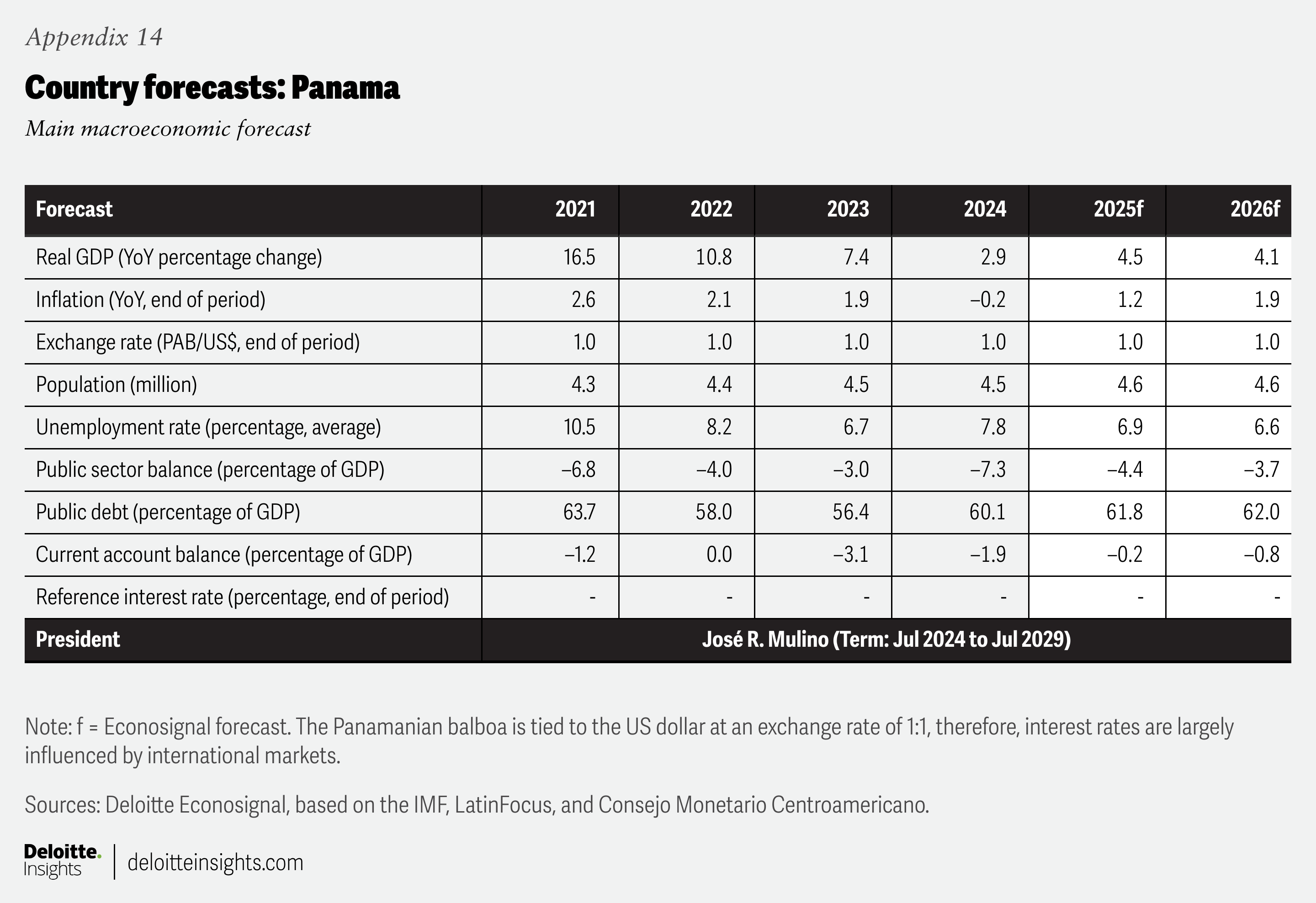

Panama: Main macroeconomic forecast

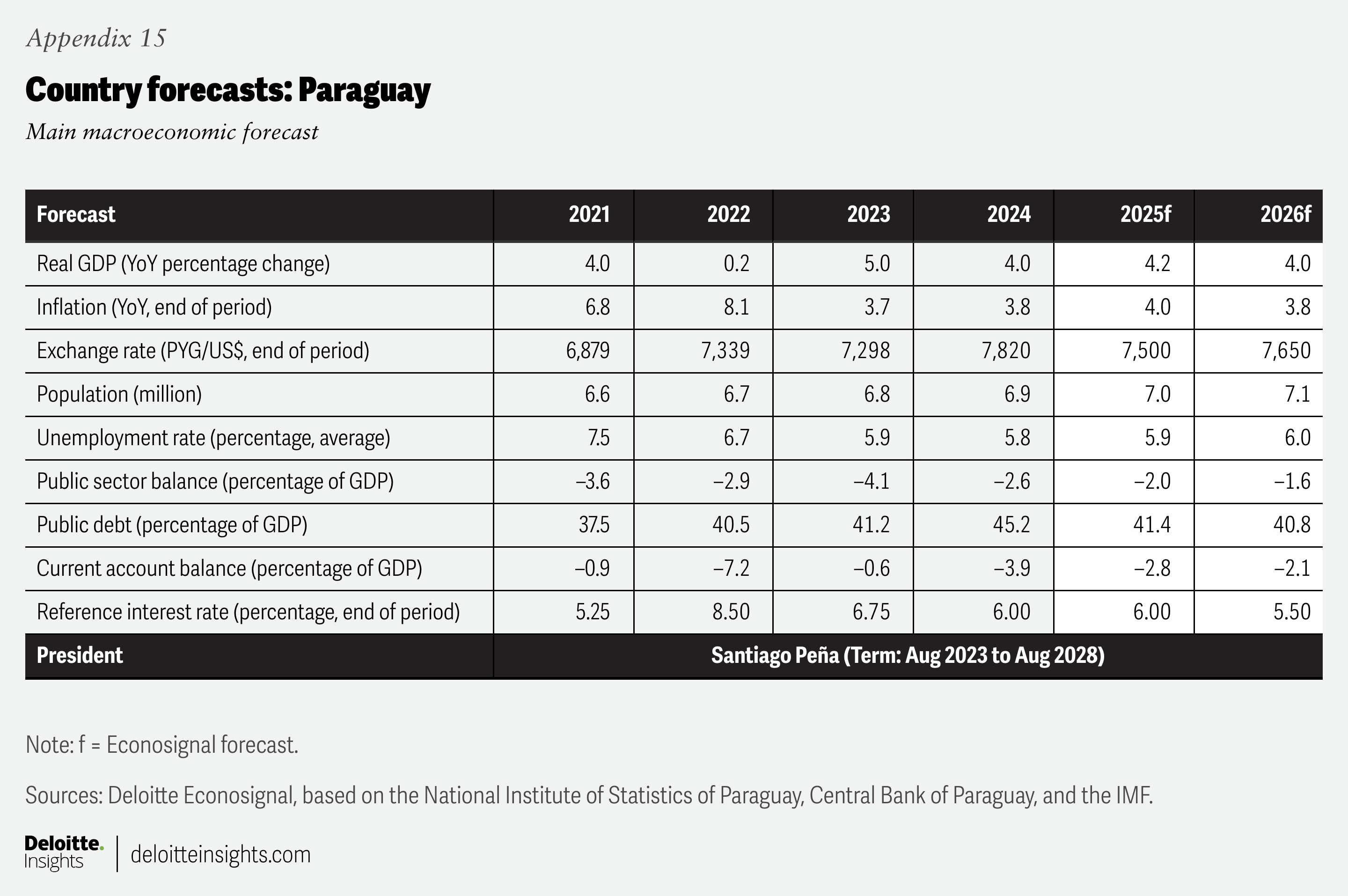

Paraguay: Main macroeconomic forecast

Peru: Main macroeconomic forecast

Uruguay: Main macroeconomic forecast

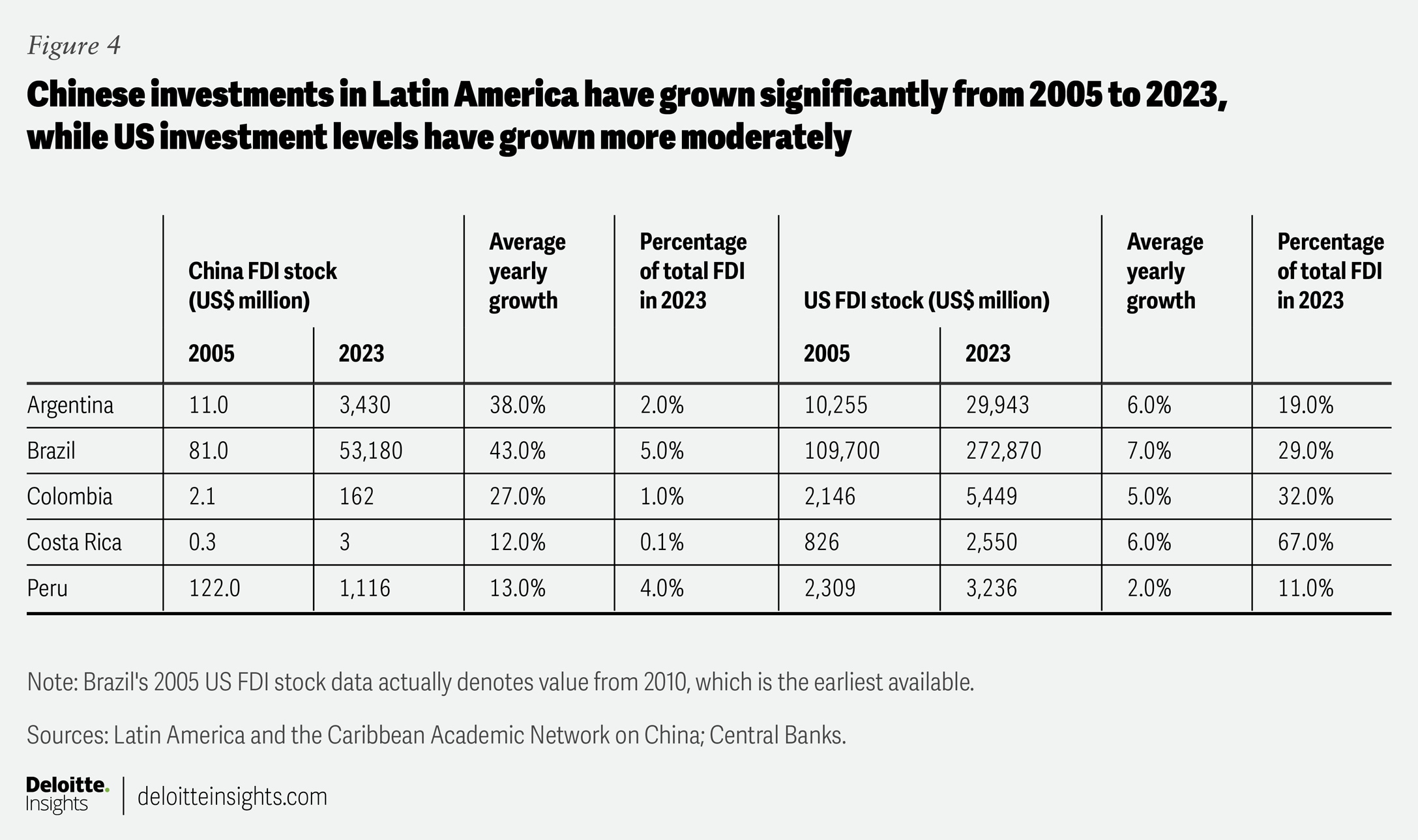

Venezuela: Main macroeconomic forecast