Brazil economic outlook, November 2025

Despite near-term challenges keeping growth in check, Brazil is likely to see economic activity pick up from next year

The Brazilian economy has slowed: Real gross domestic product growth moderated to an annualized 1.5% in the second quarter of 2025, compared with the previous quarter.1 This is down from 5.3% annualized growth in the first quarter. Government consumption and total investment both declined over the quarter, whereas consumer spending moderated to an annualized 1.9% growth rate.2 The economic activity index used by the Banco Central do Brazil suggests that economic growth may have even contracted in the third quarter.3 Although growth will likely remain subdued through the rest of the year, economic activity will likely pick up by the middle of 2026.

Some of the weakness seen in the economic statistics is unlikely to persist. For example, the drop in the economic activity index was primarily due to agriculture, which fell at an annualized rate of 16.4% between May and August.4 The ebbs and flows of agricultural economic activity have less to do with the underlying economy and more to do with environmental factors. Notably, the subindices for services and industry perked up in August. Additionally, the central bank has maintained a highly restrictive monetary policy stance. With inflation and inflation expectations coming back down, the central bank will likely provide more monetary stimulus in 2026.

The rise in inflation is likely temporary

Headline inflation cooled in October, rising to 4.7% on a year-ago basis, down from 5.2% in September, the slowest rate of price growth since January.5

Energy prices were the main reason for the easing of inflation. Unfavorable hydrological conditions caused prices to jump higher in September. Indeed, residential electricity prices were up 10.6% from a year earlier. In October, electricity price growth eased to just 3.1% after the National Electric Energy Agency reduced the red flag level from two to one between September and October. This cut the extra cost of electricity by roughly 40%.6

Apart from energy, consumer price growth has been tamer. For example, the price of groceries has eased considerably, rising just 4.5% from a year ago in October, down from 7.1% in August.7 Prices of food at home have been declining sequentially for four consecutive months. Even prices of food consumed outside the home moderated in September and October.

Monthly growth in core prices appears to have moderated recently, with the annualized monthly gain coming in at just 2% in October.8 However, year over year, core inflation is still running at 5%, only slightly lower than the 5.2% in June. This suggests Brazil is not entirely out of the woods when it comes to getting inflation back to the central bank’s target of between 1.5% and 4.5%. As a result, aggressive rate cutting remains unlikely for now.

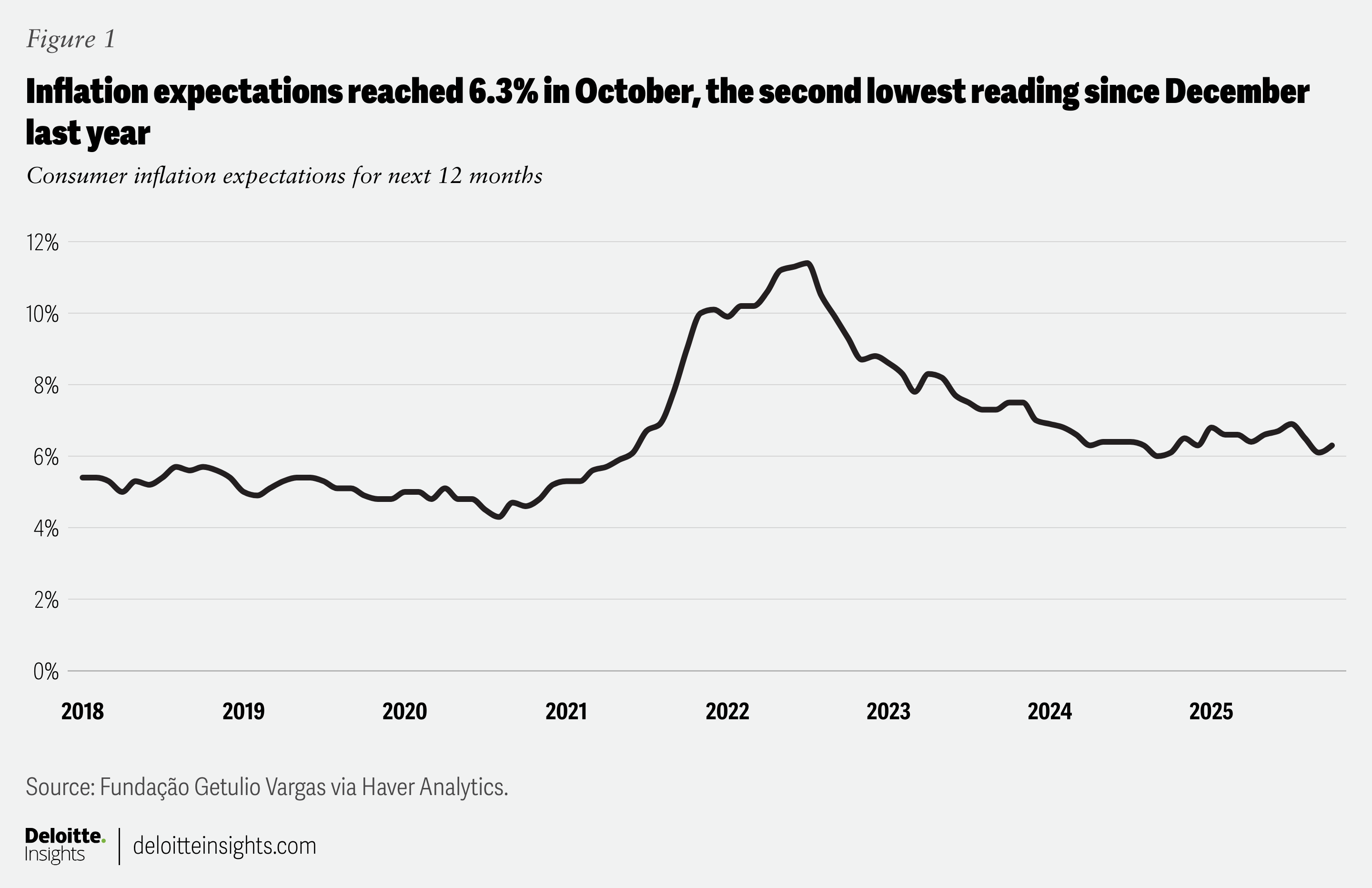

The central bank kept rates steady at 15% during its November meeting. Policymakers had vowed to keep rates elevated in an effort to tame inflation expectations and bring inflation within the target range.9 Such efforts appear to be working. Inflation expectations for the next year stood at 6.3% in October, down from 6.9% in July—the lowest since December 2024 (figure 1).10

Other inflationary pressures have been relatively weak. The producer price index was down 0.5% from a year ago in September, down from 9.6% in January.11 Although import prices have accelerated a bit, they were still up only 0.8% from a year earlier in October.12 Also, the real has remained relatively strong. Notwithstanding a currency selloff, import price inflation will likely remain muted.

Bringing interest rates down will help alleviate some stress on government finances. Despite efforts to restrain the rise in debt as a share of GDP, the central government has been running a primary deficit for five consecutive months through September.13 The primary balance excludes interest payments and needs to be in surplus to stabilize the already high debt-to-GDP ratio.

Lower interest rates would also help support consumer spending. The volume of retail sales fell in September from the previous month.14 The pace of spending has clearly slowed. Real retail sales growth averaged 3.8% in 2024 but was up just 0.2% from a year earlier in September. Spending on big-ticket items has fared the worst. Retail sales of motor vehicles and parts, construction materials, and furniture were all lower in September relative to a year ago.15

Despite the slowdown in consumer spending, consumer fundamentals remain relatively solid. The labor market continues to provide support. For example, the unemployment rate remained at 5.7% in September—tied for the lowest reading since the data series began in 2012.16 Total employment was up 1.4% from a year earlier in September. However, this was the slowest rate of growth since November 2023. Real wages also grew by 4.0% from a year earlier in September.17 Meanwhile, real restricted household disposable income was up 5.1%, suggesting that households have more purchasing power than the retail sales numbers would otherwise suggest.18

Tariffs fueling non-US trade

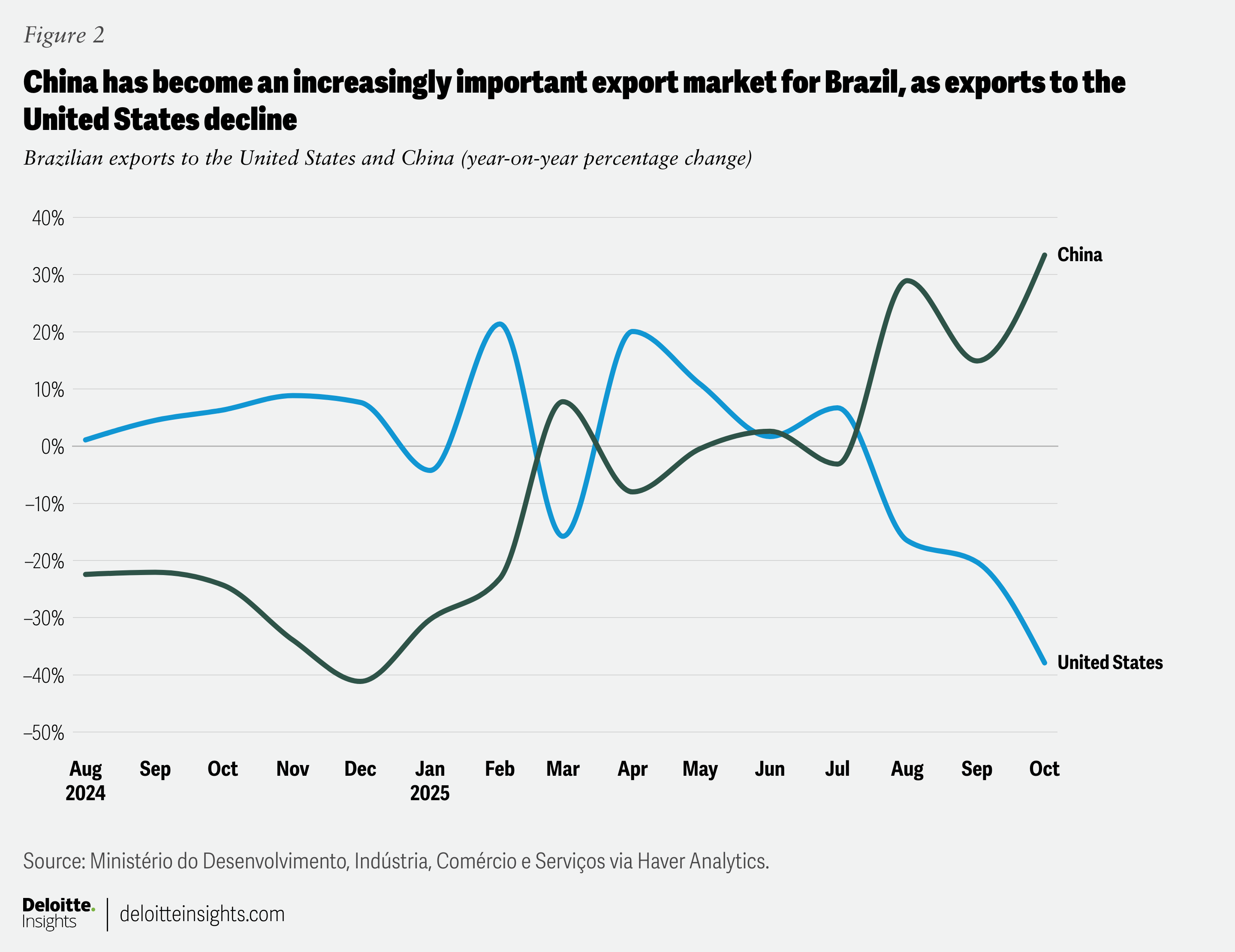

Recent data on Brazilian exports suggest that the effects of US tariffs are beginning to materialize. Year-over-year export volume to the United States fell by 17% in August and 20% in September, while exports to China rose by 29% and 15% over the same months (figure 2).19 As the US-China trade dispute continues, China has turned to alternative suppliers for key agricultural imports, especially from among Latin American nations. In response to shifting Chinese demand, Brazilian producers contributed to a 21% year-over-year increase in Brazil’s agricultural exports in October.20

The US administration implemented a 50% tariff on all Brazilian goods, which took effect on Aug. 6, 2025. The tariff combines a 10% baseline with an additional 40% levy. Despite such high tariffs, Brazilian exports continue to grow relatively quickly. Across economic sectors, Brazilian exports rose 9.1% year over year in October.21 Notably, the most significant impact has not come from tariffs imposed directly on Brazil, but rather from the indirect effects of US tariffs on China and the concomitant escalation in trade tensions.22

Meanwhile, the EU-Mercosur free trade agreement continues to move forward. In early September, the European Commission released its formal proposal to the Council for ratification. If approved, the deal will create the largest free trade zone, encapsulating a market that includes over 700 million consumers.23 The agreement is expected to eliminate tariffs on over 90% of bilateral trade. South American farmers will gain greater access to European markets, while Mercosur’s protected markets will open to European industrial goods.24

While the agreement will drive additional demand for Brazilian agricultural goods, it also risks deepening Brazil’s economic reliance on commodity exports at the expense of higher-value manufacturing and services. This dynamic could reinforce Brazil’s exposure to the middle-income trap by reducing the need for productivity-driven growth, thereby constraining long-term growth potential.

Separately, the US Section 301 investigation of Brazil remains ongoing. The United States cited anticompetitive digital trade and electronic payment services policies, an unfair tariff regime, and illegal deforestation.25 Yet, deforestation hit a 15-year high back in 202126 and decreased by 31% from August 2023 to July 2024 compared with the prior year.27 The current administration has pledged to eliminate illegal deforestation by 2028.

For many, deforestation is seen as the only viable pathway to further economic development. For example, in 2024, soybeans, meat, wood, and metals accounted for approximately 40% of Brazil’s exports, much of which originated from cleared lands in the Amazon.28 Additionally, 70% of Brazil’s energy comes from hydropower generated by dams in the Amazon.29 Already, about 25% of the Brazilian Amazon has been cleared for agriculture, livestock, and mining.30

Rising demand from both China and Europe will likely place upward pressure on Brazil’s supply of agricultural products and lead to increased deforestation. Yet recent reports suggest that preservation of the Amazon rainforest and Brazil’s economic growth are not mutually exclusive. A study by the World Research Institute in Brazil found that, rather than reducing output, more efficient land use and energy production, a larger bioeconomy, and investments in sustainable agriculture and livestock practices could grow the region’s GDP by roughly US$8.2 billion annually by 2050.31

Despite near-term challenges to growth, Brazil’s economy is likely to rebound next year. Falling inflation will allow the central bank to ease policy, which will likely improve domestic demand. Meanwhile, despite high barriers to trade with the United States, demand for Brazilian goods is rising. Indeed, Brazil is benefiting from US trade tensions with China and the European Union—a common trend among its Latin American peers.