Argentina economic outlook 2025

Argentina enters a phase of macroeconomic rebalancing despite key challenges

Over the past decade, Argentina has gone through economic cycles marked by broad fiscal and monetary imbalances, high inflation levels, and economic volatility. However, recent data hints at a structural change in the country’s economic model, based on three primary pillars:

- Fiscal consolidation: Argentina achieved a fiscal surplus for the first time since 2006. This fiscal consolidation is the basis for stabilizing expectations and reducing dependence on financing.

- Expansion of strategic sectors (energy and mining). Development of the Vaca Muerta shale, including unconventional extraction methods and improved infrastructure, is positioning Argentina as an important regional energy exporter.1

- Regulatory framework. The Incentive Regime for Large Investments or “RIGI” is built upon three pillars—fiscal, customs, and foreign exchange—and seeks to attract long-term investments in the forestry, industry, tourism, infrastructure, mining, technology, steelmaking, energy, oil, and gas sectors.2

The question, however, remains whether this transformation has a solid foundation and if government policy will support it.

Argentina economic overview

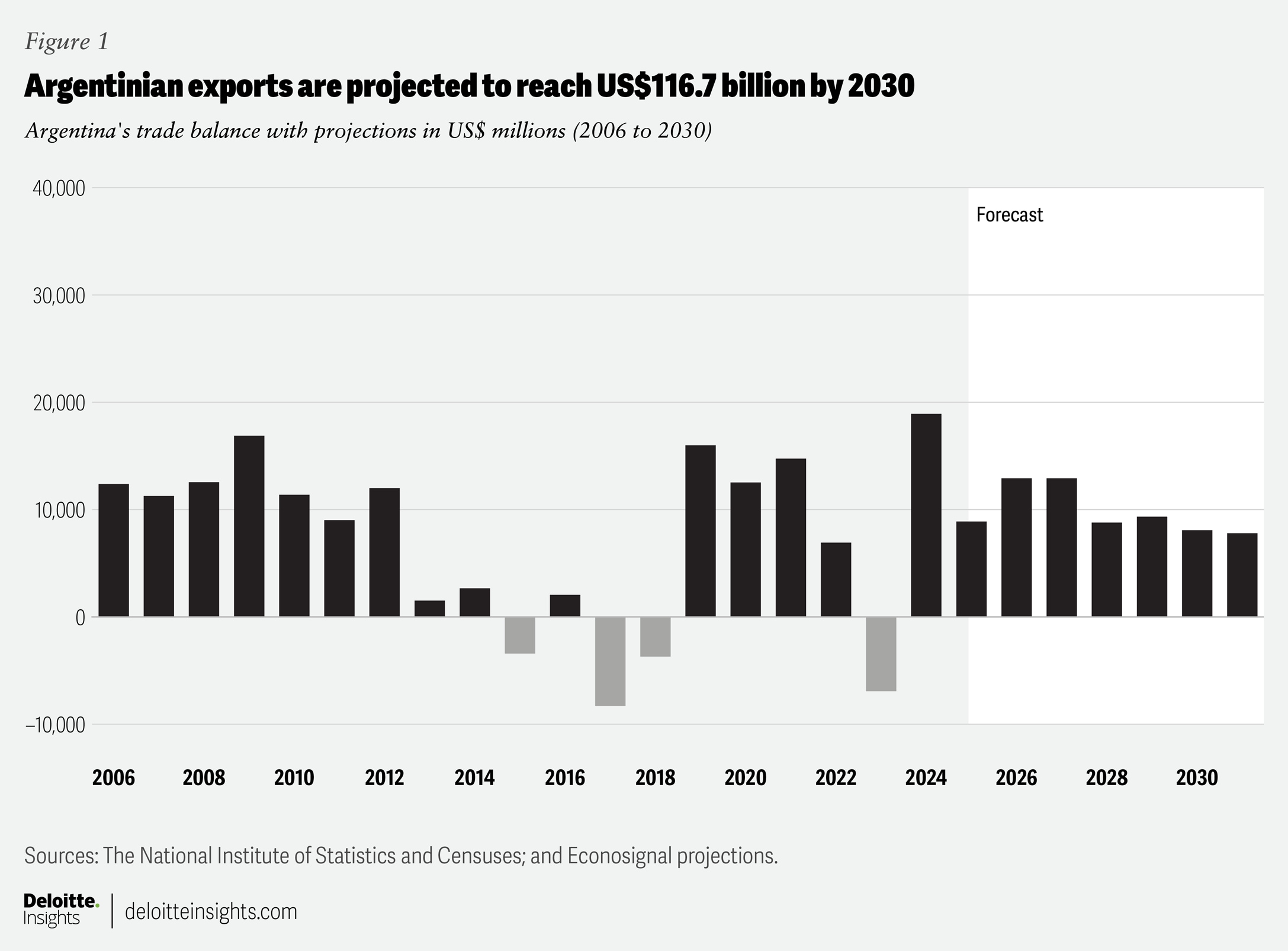

Between 2013 and 2023, Argentina’s trade balance was in a state of flux, with moderate surpluses recorded during recessions and deficits during periods of import-led growth. The turning point came in 2024, when the surplus reached a record level of roughly US$19 billion,3 driven by a recovery in the agricultural sector after the drought of 2023, an increase in energy exports, and a fall in economic activity.

In 2025, despite the recovery in economic activity (a cumulative increase of 5.2% as of August 2025 compared with the same period in 2024) and imports (a cumulative year-on-year growth of 35%), a cumulative balance of US$6.4 billion was recorded as of September. This reflects the reactivation of the economy and the rising demand for capital goods.

Deloitte projections are optimistic: Total exports are expected to grow from US$79.7 billion in 2024 to US$116.7 billion in 2030,4 with sustained positive trade balance levels, mostly driven by energy and mining (figure 1).

Argentina invests in its oil, gas, and mining sectors

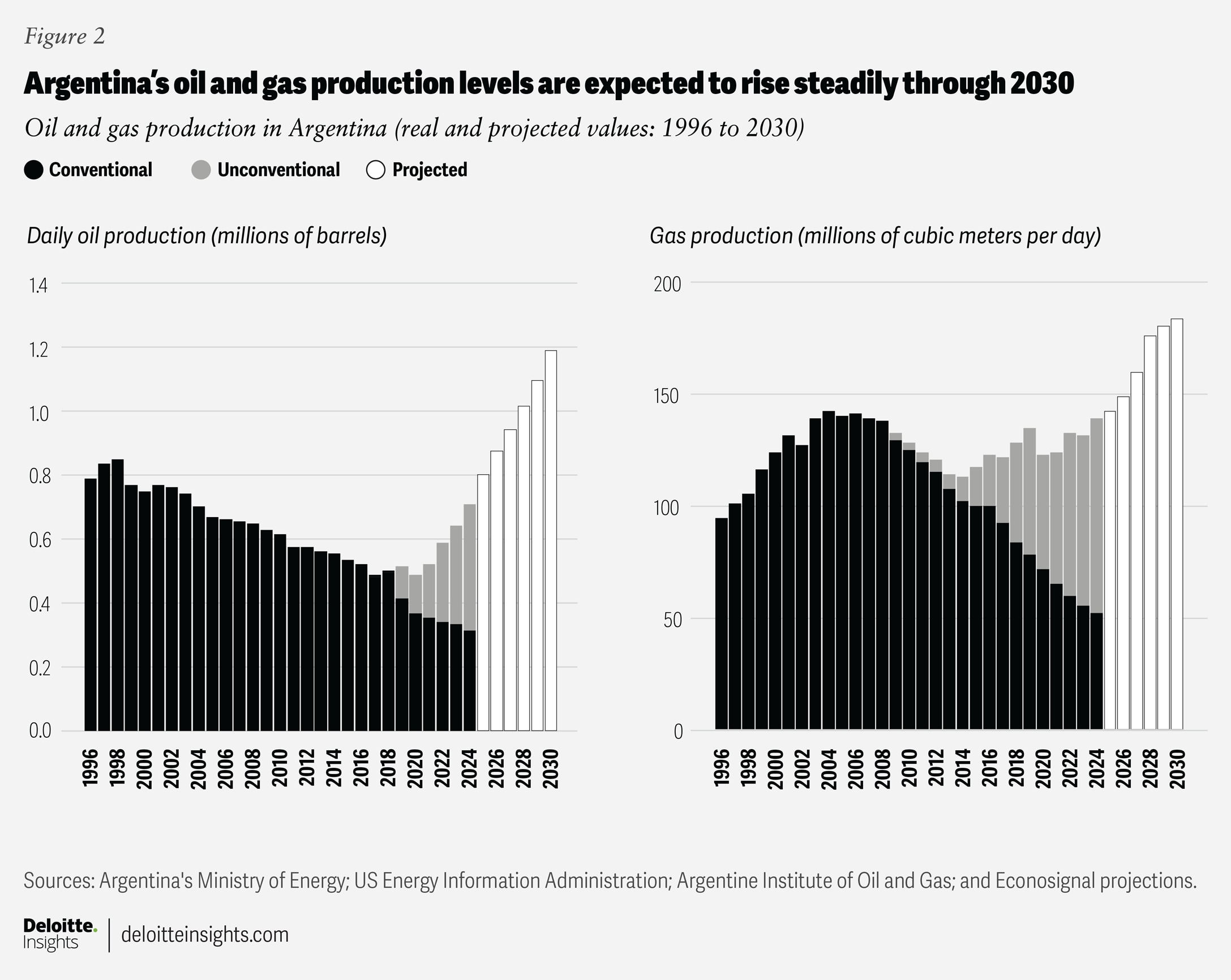

Oil and gas production is on an upward trend from the lows seen in 2021. In 2025, average crude oil production will likely reach 805,000 barrels per day (a 13% growth year on year), while gas production is projected to reach 143.3 million cubic meters per day (a 3% growth year on year).5

This robust performance is driven mainly by the development of the Vaca Muerta shale, Argentina’s main unconventional oilfield. Projections by the Argentine Institute of Oil and Gas and the International Energy Agency anticipate strong growth for the sector: By 2028, crude oil production will likely exceed 1 million barrels per day and, according to Deloitte calculations, up to US$19 billion per year in foreign exchange could be generated through 2030 (figure 2).6

This export leap, however, depends on investments in critical infrastructure, such as pipelines and plants for liquefied natural gas—already underway under the RIGI. The investment in liquified natural gas exports registered under the RIGI alone amounts to almost US$6.8 billion in the first 10 years and another US$15 billion over the following 20 years, across the value chain.7

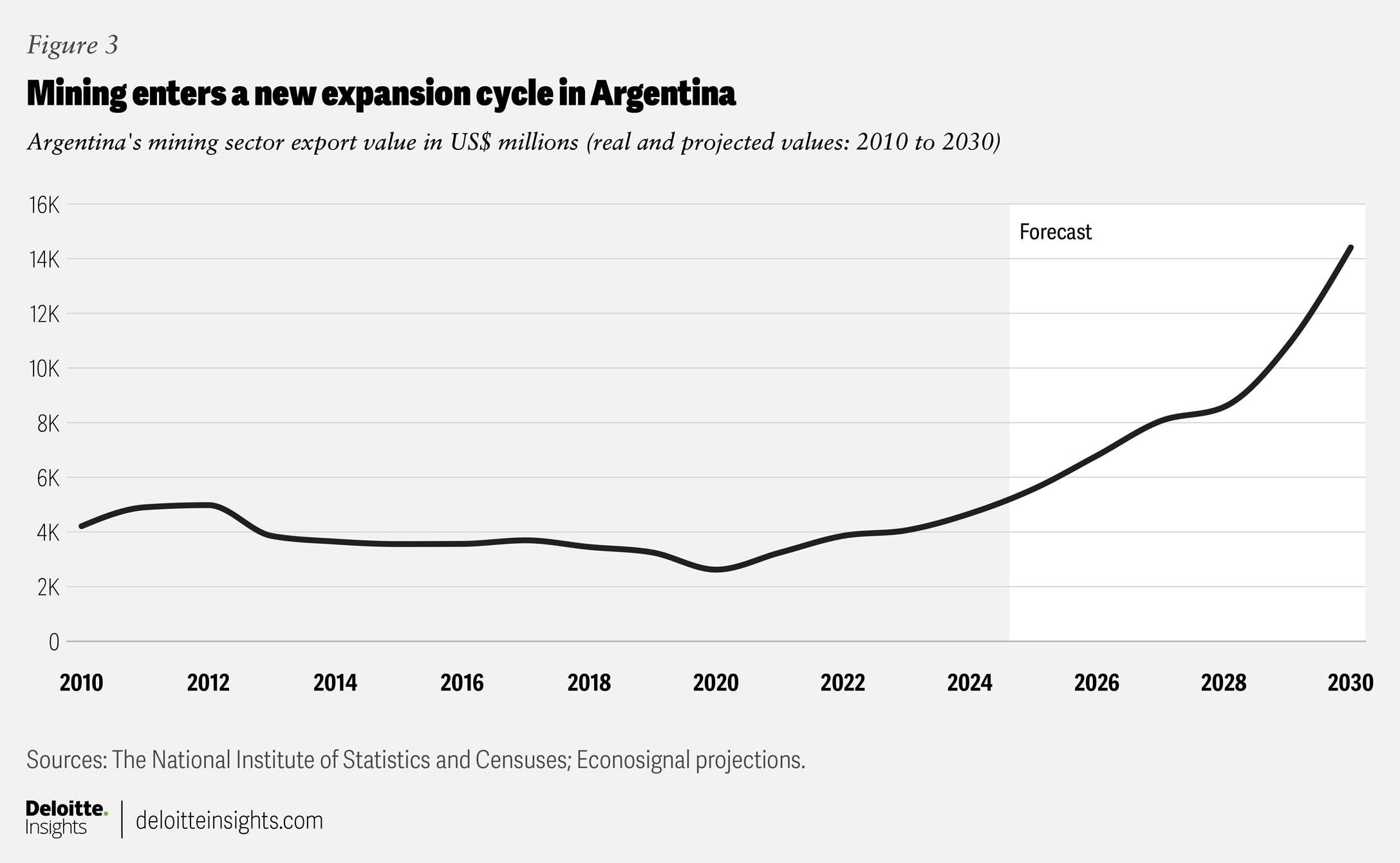

The mining sector is also experiencing an expansion phase (figure 3). In 2025, mining exports will likely reach US$5.5 billion (a 4.83% year-over-year growth), with gold contributing 69%, silver 12%, and lithium 14% (figure 3).8

Estimated production for 2025 includes 1.1 million ounces of gold, 19.6 million ounces of silver, and 130,000 tons of lithium carbonate equivalent. The potential is enormous: Deloitte Econosignal estimates investments of US$51.9 billion by 2035,9 mainly in copper and lithium, with projects like Los Azules (copper) and Rincón (lithium) being major examples.

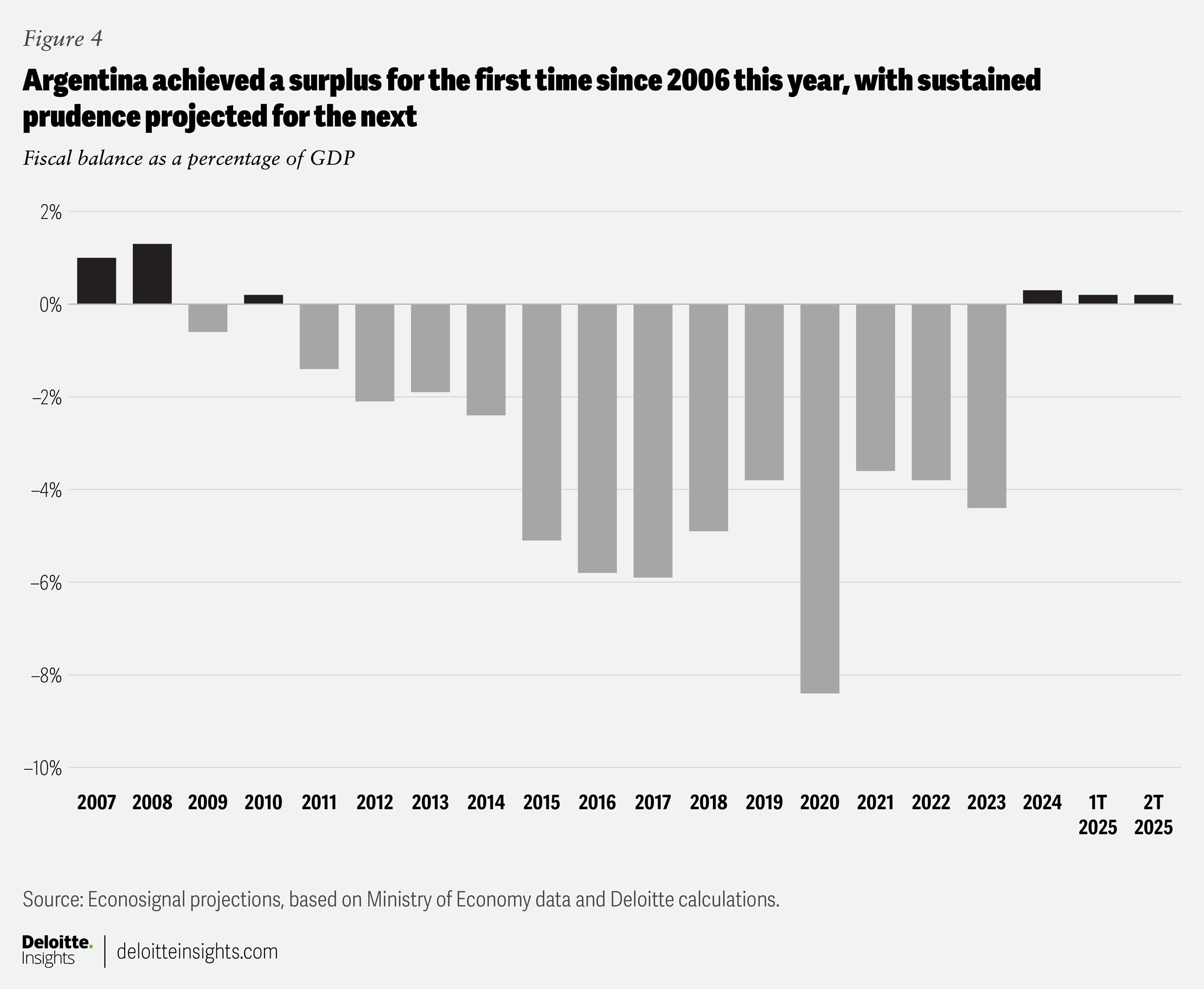

After years of chronic deficits, in 2024, Argentina achieved a primary and financial surplus for the first time since 2006—with a fiscal surplus of 0.3% of GDP.

The RIGI plays a key role in offering fiscal stability and free foreign-currency availability, conditions that seek to attract capital and make large-scale projects viable in a global context of energy transition.

So far, 20 initiatives have been presented, exceeding US$33 billion, of which eight have already been approved, focusing on the energy, mining, and steelmaking sectors.10 The regime aims to break the short-term logic that characterizes the Argentine economy, offering predictability over a 30-year horizon.

Fiscal consolidation

One of the most significant changes contributing to Argentina’s greater macroeconomic stability—and therefore a better investment outlook—has been the country’s fiscal balance. After years of chronic deficits, in 2024, Argentina achieved a primary and financial surplus for the first time since 2006, with a fiscal surplus of 0.3% of gross domestic product.

In 2025, the cumulative result through June shows a primary surplus equivalent to 0.9% of gross domestic product and a financial surplus of 0.4% (figure 4), with the economy expected to end 2025 with an overall surplus of 0.2%. This is explained by reductions in subsidies and spending across various areas of the government, despite the elimination of the PAIS tax (tax on foreign currency transactions) and export duties.

Looking ahead to 2026, the government has already sent the budget to Congress for review, and it indicates that fiscal prudence will continue, projecting a primary surplus of 1.5% of GDP and balanced consolidated fiscal accounts.

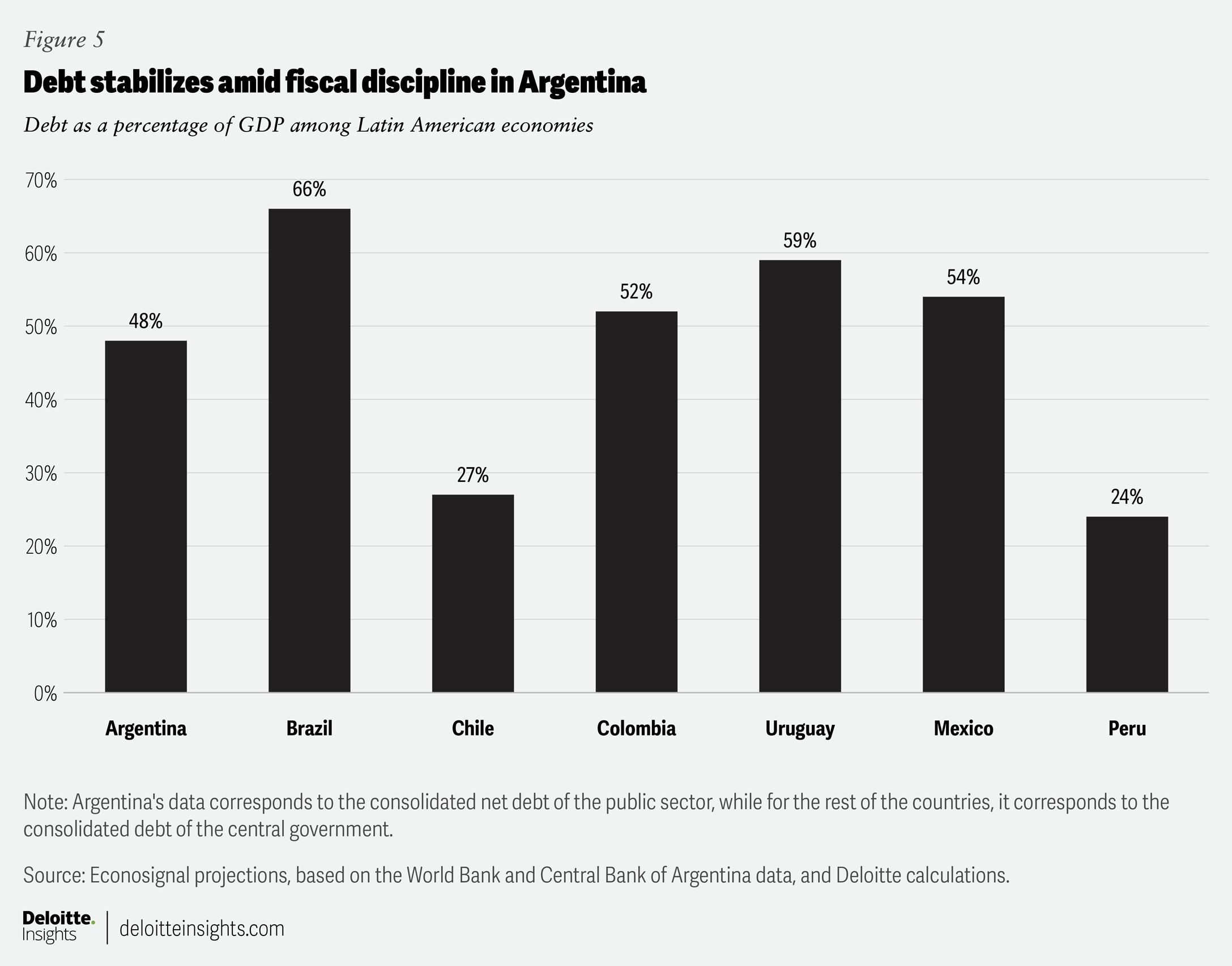

Fiscal adjustment has implications for debt as well, since balanced fiscal accounts reduce the need for additional financing. According to Deloitte calculations, as of December 2025, the net debt of the consolidated public sector will likely reach US$29.3 billion—equivalent to 48% of GDP—a level similar to other countries in the region (figure 5).

If the growth path continues and there is greater access to international capital in a way that allows debt refinancing, Argentina’s debt levels will not be as alarming.

Argentina’s political environment

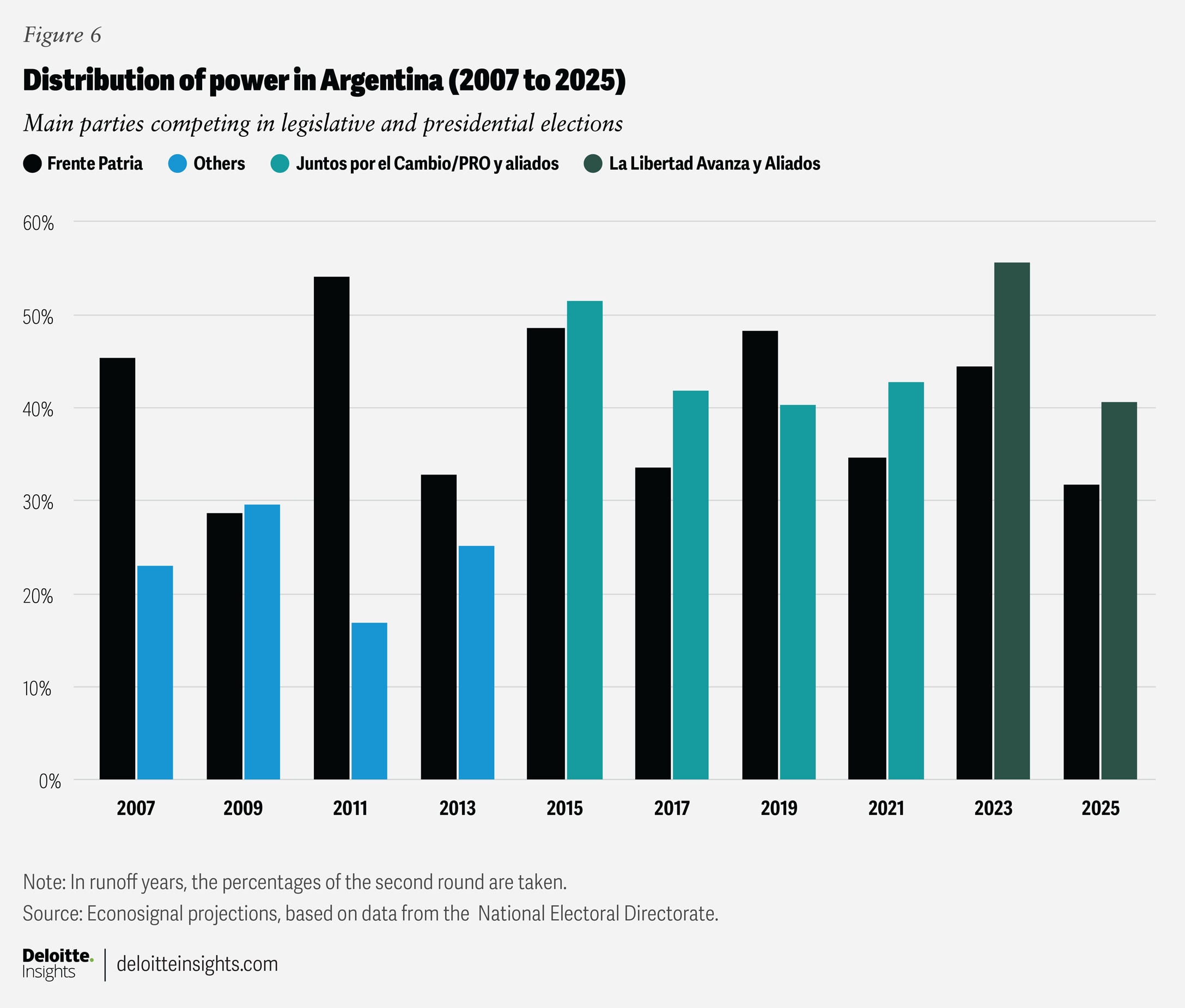

Economic change does not happen in a vacuum; it needs political backing. From 2015 to 2025, the balance of power in Argentina has been evenly poised between the first and second most powerful forces in the elections, making consensus imperative to implement regulatory reform.

In the 2025 legislative elections, the Justicialist Party (under the brand Fuerza Patria) obtained 31.7% of the vote, compared with 40.7% for the party in power, La Libertad Avanza (figure 6). This distribution reflects a fragmented scenario but demonstrates the government’s capacity to sustain power.

The change in the economic model has only partial electoral support: Despite not having full consensus, there is a sufficient basis for the government to advance structural reforms, especially if the benefits (such as employment, foreign exchange, and growth) materialize in the short term.

Data suggests that Argentina is pivoting: The combination of fiscal surplus, export expansion in energy and mining, and a pro-investment regulatory framework is creating a growth scenario that would have been unprecedented in the last decade.

However, risks remain, such as political volatility, dependence on international prices, and infrastructure bottlenecks. Is it different this time?

The answer will depend on the country’s ability to sustain fiscal discipline, execute committed investments, and maintain a minimum level of stability in economic policies. If these factors align, Argentina could leave behind its cycle of recurrent crises and consolidate a model based on external competitiveness and macroeconomic balance.

For Deloitte’s analysis of the macroeconomic conditions affecting Latin American economies, read Deloitte’s Latin America economic outlook 2025.