Beyond office walls and balance sheets: Culture and the alternative workforce

Deloitte Review, issue 21

The more things change, the more culture matters

Learn more

WHILE organizational culture may be difficult to define and tricky to manage, it can have a powerful impact on individual and corporate performance. Research shows that organizations that cultivate a positive culture around a set of shared values have an advantage over competitors: Workers who perceive their very human need for meaning and purpose as being met at work exhibit higher levels of performance and put in greater discretionary effort.1 Beyond simply work output, culture is also a powerful driver of engagement, which has been linked to better financial performance.2 This is why, at many organizations, leaders strive to deliberately shape a culture that encourages employee effort and collaboration around a shared set of values.

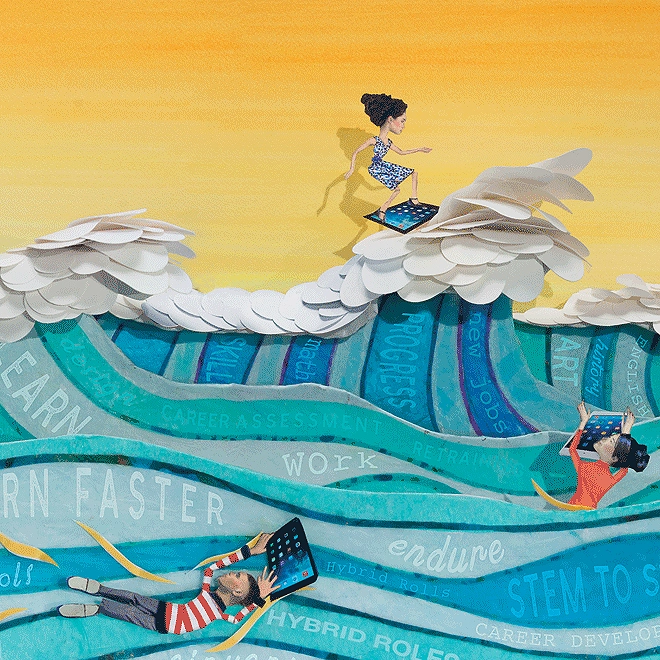

However, how confident can leaders be that their efforts to disseminate organizational culture are reaching all of the people they employ? Today, two factors present organizations with new and unique challenges to creating purpose and connection across their entire worker base. First, technology is enabling more and more people to work remotely, physically removing a portion of the workforce from the corporate or local campuses where employees used to congregate. And second, contingent, or “off-balance-sheet,” workers are making up a growing proportion of the workforce—and these workers may not necessarily feel the same investment in an employer’s mission and goals that a traditional employee might.

Imbuing culture to the remote and contingent workforce may not seem to carry much urgency at companies where such “alternative” work arrangements have historically been few and far between. But when faced with rapid societal and technological change, many of these companies will likely at least begin to experiment with remote and contingent work arrangements, as social mores shift and the technological enablers become less expensive. In fact, 95 percent of net new employment in the United States between 2005 and 2015 consisted of alternative work arrangements, and the number of workers engaged in alternative work arrangements steadily grew from approximately 10 percent in 2005 to nearly 16 percent by 2015.3 This number is expected to continue to grow: A recent Intuit report predicts that nearly 40 percent of all US workers will be engaged in some sort of alternative work arrangement by 2020.4 In addition, a 2015 Gallup poll revealed that the number of employees working off-campus has grown nearly fourfold since 1995, with 24 percent of workers noting they mostly telecommute.5

Under the new realities of the distributed and contingent workforce, employers face the growing challenge of fostering a shared culture that encompasses all of their workers, on- or off-campus, on or off the balance sheet. In this effort to achieve consistency of culture across all worker types, both location and employment type have distinct implications; therefore, leaders need to develop a nuanced strategy to extend organizational culture to alternative types of workers.

The case for creating a positive organizational culture

People need meaning and purpose in their lives. Caring about why we do what we do and what good it creates is an essential feature of being human: Research suggests that we all have an innate desire to find meaning, achieve mastery, and be appreciated.6 These motivations don’t check themselves at the door when we walk in to work; in fact, work often amplifies them.7 As a recent Harvard Business Review article noted, “What talented people want has changed. They used to want high salaries to validate their value and stable career paths to allow them to sleep well at night. Now, they want purposeful work.”8

Workers’ sense of meaning in their work can be significantly enhanced through a culture that is built upon shared values. In essence, a positive organizational culture is one in which social norms, beliefs, and behaviors all reinforce the value of pursuing a shared goal.9 A shared culture clearly defines how the organization’s and individual’s efforts are making a difference. And while individuals may find purpose in their work regardless of their employer’s culture, it’s reasonable to suppose that being part of a shared culture can play an important role in amplifying that sense of purpose. In fact, studies suggest that workers rate “personal satisfaction from making a difference” as a more important criterion of success than “getting ahead” or even “making a good living.”10

Organizations that can meet people’s needs for meaning and recognition in their work are much more likely to perform at higher levels. Compelling research shows that companies that pursue purpose as well as profits outperform their counterparts by 12 times over a 10-year period.11 Deloitte’s own research suggests that “mission-driven” organizations have 30 percent higher levels of innovation and 40 percent higher levels of engagement, and they tend to be first or second in their market segment.12 For example, Unilever launched its Sustainable Living Plan program in 2009, which focused on establishing a sense of purpose among its employees as a key business outcome. Not only did employee engagement scores substantially rise as a result, but earnings per share increased from $1.16 to almost $2.13

The four faces of the alternative workforce

Some companies already recognize the challenges of maintaining a consistent culture across locations and extending it to people in alternative workforce arrangements. Consider the challenge that Snap Inc., the parent of Snapchat, acknowledged when it filed its IPO. Snap Inc. broke the Silicon Valley mold by launching its IPO without a designated corporate headquarters. In its IPO filing, the company noted that this strategy was a risk that could potentially be harmful, explaining, “This [diffused] structure may prevent us from fostering positive employee morale and encouraging social interaction among our employees and different business units.”14

Figure 1 shows how the workforce can be segmented along two axes: location—on- vs. off-campus—and contract type—on- vs. off-balance sheet. Considered in this way, the workforce broadly falls into four segments, each presenting distinct challenges with regard to propagating organizational culture. Note that these axes are fluid in nature; in particular, many workers in certain industries, such as professional services, may split their time between off- and on-campus locations (indicated by the gradient area in figure 1). These workers may be considered “hybrid” workers who experience some of the cultural advantages of on-campus work, while also facing some of the challenges experienced by the remote worker.

The traditional worker. Perhaps the most familiar, the traditional employee works on-campus, in a full-time or fixed part-time arrangement. Given a shared location and regular in-person interactions, social norms and behaviors are generally highly observable among traditional workers, making this setting the most efficient at transmitting culture. But these benefits come at a cost: the overhead involved in maintaining a physical location or multiple locations, as well as the risk of cultural stagnation. Also, if norms are well entrenched, an on-campus setting has the potential to create a static or homogeneous culture that can be difficult to change—an ability that may be crucial as companies increasingly demand nimble and dynamic environments to remain competitive. The risk is that groupthink may arise, leading workers to conform to old ways of acting and thinking rather than challenging the status quo.15 In addition, traditional workers in satellite locations may feel isolated from headquarters, which can foster resentment or a sense of being “second-class citizens.”

The tenured remote worker. Off-campus but on-balance sheet workers are commonly referred to as teleworkers, but they may also include traveling salespeople, remote customer service workers, and those in other jobs that do not require on-campus accommodations. These workers have flexibility of location, but are at a disadvantage when it comes to actually observing social norms as well as experiencing in-person collaboration. Research suggests that remote employees often have less trust in each other’s work and capabilities due to a lack of interpersonal communication.16 In addition, remote workers may feel isolated and separated from the company’s headquarters. However, companies still have some traditional levers to pull to engage the tenured remote worker, such as benefits and formal career progression opportunities.

The transactional remote worker. This type of worker is not only off-balance-sheet, but also off-campus. Often, they are paid to deliver very specific services. Many of these individuals operate on flexible schedules and in customer-facing roles.17 Their relationship with the hiring organization can be marked by low-quality touchpoints and facilitated through technology-based platforms or a third-party agency. The transactional remote worker may also experience a strong sense of instability, which may result in added anxiety.18

The outside contractor. On-campus but off-balance-sheet, contract or consulting workers often bring an inherent outsider mentality and an array of previous cultural experiences. They are often brought in to help facilitate a shorter-term or finite project and may be viewed—or may view themselves—as not being subject to the organization’s cultural norms and values. These workers usually do not receive the typical onboarding and new hire training opportunities that can help build a sense of culture among on-balance sheet employees. Given that these individuals work on campus and can observe the organization’s norms firsthand, however, there may be more opportunities to make them feel like part of the culture.

Creating a shared cultural experience across a segmented workforce

Creating a consistent culture across these four unique talent segments requires strategic grounding, as a positive organizational culture is not likely to thrive without focus, intention, and action. While culture may often be viewed as an intangible asset, and even as an emotional or personal aspect of business, using a strategic framework can help bring culture to the forefront of leadership decision making.

Just as broader organizational strategy must be crafted deliberately, culture must also be intentionally shaped to make workers feel valued and perform well. Asking a series of questions specifically focused on managing culture can help to guide organizations as they work to sustain and extend their mission amid the growth of alternative work arrangements. Based on the strategic choice cascade—a well-developed framework that is often used to help make intentional decisions about an organization’s strategy19—this approach applies similar principles in thinking about how to sustain culture across all four workforce personas (figure 2).

What is our culture and purpose?

To leverage culture as an asset to organizational performance, organizations must first have a clearly articulated culture—one whose norms and values support the advancement of the organization’s purpose and mission. This may seem self-evident, but just 23 percent of the respondents to the 2017 Deloitte Global Human Capital Trends survey believe that their employees are fully aligned with their corporate purpose.20 This is an alarming disconnect, with research suggesting that purpose misalignment is a major underlying cause of the rampant disengagement facing many organizations today.21

A strong corporate purpose—however one defines it—can yield dividends, not just for workforce engagement and productivity, but for the brand and company growth as well. Patagonia, the global outdoor clothing manufacturer, cultivates a positive organizational culture by fostering a sense of commitment, shared beliefs, collective focus, and inclusion. For years, the company has been known for its high-end outdoor clothing and bright-colored fleece jackets. Beyond its products, however, the company also emphasizes environmental sustainability. Sometimes known as “the activist company,” Patagonia’s mission statement reads, “Build the best product, cause no unnecessary harm, use business to inspire and implement solutions to the environmental crisis,” and the company infuses this approach into its work environment.22

Patagonia’s leadership has implemented and reinforced a culture that motivates employees of all types to play an active role in environment sustainability and live by its mission statement. Employees around the world are given opportunities to participate in programs and initiatives that support the environment; the company donates either 1 percent of total sales or 10 percent of pre-tax profits (whichever is greater) to grassroots environmental groups; and the company takes steps to ensure that the materials and processes used to manufacture their products are environmentally friendly. Through activities like these, Patagonia leaders strive to build an emotional attachment to the company’s mission across its employee base.

How do we improve cultural fit?

As organizations continue to leverage alternative workers more and more, it will become increasingly important to obtain consistent, high-quality work products from this talent segment. To reduce onboarding, training time, and costs, companies may opt to create a consistent group of alternative employees who work regularly with the organization. Workers who are naturally a good fit for an organization’s culture get along well with the other employees, have a positive experience during their time with the organization, and experience the sense of belonging that can fuel discretionary effort. Therefore, an important step is to screen alternative workers, particularly the transactional remote employees—individuals whose employment relationship was long considered purely transactional—for cultural fit before hiring them. Employers can leverage an array of digital technologies, including video interviews, online value assessments, and even peer-rated feedback, to determine fit throughout the hiring process. Particularly in contexts where teaming and collaboration are important, screening contingent workers for fit during the recruiting process is the first line of defense against diluting an organization’s culture.

TaskRabbit, an online marketplace that matches freelance labor with demand for minor home repairs, errand running, moving and packing, and more, understands the value of assessing potential workers—or “taskers,” as they call them—for cultural fit. After seeing early missteps by peers in the gig economy who did not accurately screen or ensure quality of work, TaskRabbit started an early process during the recruiting phase to heavily screen all potential taskers.23 Now, each tasker goes through a vetting process, which includes writing an essay, submitting a video Q&A, passing a background check, and completing an interview.24 Additionally, each tasker is reviewed by customers who book his or her services via TaskRabbit’s platform. That feedback helps TaskRabbit ensure that its taskers are demonstrating the company’s desired culture. “The marketplace is all about transparency and performance. You have people out there providing your product that aren’t your employees,” says TaskRabbit CEO Stacy Brown-Philpot. “But you still have to put out there what your values are.”25 Organizations can use a screening process like TaskRabbit’s, not just for their contingent workers, but for their traditional and full-time remote employees as well.

How do we create a consistent employee experience among our unique segments?

While cultivating a shared organizational culture is important, it is also important not to assume that a one-size-fits-all strategy for shaping the cultural experience across the organization will be effective. This is where the segmentation depicted in figure 1 comes into play. Your organization may depend on a variety of worker arrangements to achieve its business goals; ensuring that your culture is experienced and reinforced consistently across all worker types, albeit through different mechanisms, is key. Indeed, each worker segment is likely to experience the organizational culture from a different perspective. Developing a strong organizational culture can ensure that each segment is valued for their contributions toward a shared goal. Here are some recommendations on how to approach each segment:

- Traditional workers. Physical spaces can certainly be the most expensive to maintain, but they can also be the most effective in helping to shape an organization’s desired culture. Consider how your organization’s space is designed and what that signals to your traditional workers. Leverage the physical space to reinforce a commitment to your purpose. One financial services firm, seeking to create a culture that emphasized a strong commitment to relationships with advisors and employees, sought to redefine the company’s culture by starting with some low-hanging fruit.26 Initial activities included dedicating a wall to employee pictures, renaming conference rooms, and reconfiguring office spaces. Over time, town halls were moved from a formal meeting space to an open floor space where employees could easily mingle with senior leaders afterward. Senior leader parking spaces were removed to signify that all workers’ efforts were important to the company’s success. Cubicles were reorganized into team pods to encourage cross-functional collaboration. In addition, the company began a quarterly human-centric award that publicly recognized employees who demonstrated the company’s core values. Utilizing the physical space to create intentional employee experiences helped to reshape the company’s culture around its purpose.

- Tenured remote workers. Make working remotely as simple as possible for this employee segment. Invest in technologies that support digital collaboration and make working and connecting from off-campus easy. As feelings of being excluded from the goings-on can sometimes plague remote workers, take care to include tenured remote workers when scheduling ad hoc meetings where their involvement would be valuable. In addition, consider creating opportunities for these workers to interact in person with other employees—for instance, through annual retreats or local lunches—to encourage trust and team-building. Lastly, this can be an easy group to overlook when it comes to recognition and acknowledgment of milestones. Openly reward and acknowledge tenured remote workers’ efforts using venues such as company-wide town halls or newsletters. For example, the financial firm discussed above relied heavily on tenured remote employees to fulfill its customer service requests. In an effort to extend the culture beyond the organization’s physical walls, leaders highlighted one remote employee’s exceptional customer service through the company-wide newsletter. This relatively small act of recognition went a long way in helping to reduce turnover within this segment of its employee population.

- Transactional remote workers. Take the time to understand what these workers are hoping to gain from their temporary assignment, and use this understanding of their needs to build their commitment to your company and its culture. In many cases, transactional remote workers are foregoing traditional worker benefits in exchange for greater freedom and flexibility. Don’t micromanage, but rather, acknowledge their ability to be autonomous and make it clear that you support their flexible work arrangements. In addition, because transactional remote workers aren’t around all the time, Daniel Pink, author of Drive, recommends “spending extra time talking about what the goal is, how it connects to the big picture, and why it matters.”27 Understanding their reasons for accepting the assignment and providing greater context for how their work fits into the larger picture can help leaders better transmit their organization’s culture to the transactional remote worker.

- The outside contractor. Because this segment of the alternative work population works within your campus, their physical presence can be leveraged to communicate culture through means such as inviting them to all-company meetings and encouraging their participation in lunches or after-work activities. A recent Harvard Business Review article also provides this advice when working with the outsider employee segment: “Try to avoid all the subtle status differentiators that can make contractors feel like second-class citizens—for example, the color of their ID badges or access to the corporate gym—and be exceedingly inclusive instead. Invite them to important meetings, bring them into water-cooler conversations, and add them to the team email list.”28 Stated simply, don’t overlook these employees working right in front of you and err on the side of greater inclusion in communications, meetings, and company-wide events.

What capabilities and reinforcing mechanisms do we need to extend our culture?

Leaders should identify both the organizational capabilities and the tools and mechanisms required to help reinforce the desired culture through operations (for example, speed, service, delivery, tools). All aspects of operations should support the desired organizational culture. For instance, if leaders want the culture to encourage continuous learning, they can put in place easily accessible training to upskill employees or reinforce key capabilities or skill sets. Additionally, rewards will come into play as a key reinforcing mechanism; after all, the activities you reward are the ones that employees focus on, so use rewards to reinforce the behaviors that are important to your organization.

Airbnb, a home-sharing platform through which travelers can rent a room or an entire home, reinforces culture through a variety of mechanisms. In addition to up-front screening mechanisms of potential hosts, the Airbnb application includes questions about hospitality standards and asks for a commitment to core values that hosts have to agree to support. Airbnb reinforces these values in several ways. First, it has a Superhost program to reward hosts who exemplify Airbnb’s culture. These Superhosts, who now number in the tens of thousands, can earn revenue in the five- to six-figure range; the Superhost designation helps to propel their rentals, creating an incentive that hosts strive to attain. Superhosts also receive a literal badge of honor for their profiles.29 Airbnb evaluates hosts based on nine criteria, from tactical factors around reliability and cleanliness to the host’s experience, communications with guests, and number of five-star reviews. These evaluations also help align hosts with Airbnb’s values and purpose.30 Additionally, Airbnb holds host meetups for knowledge-sharing and community building.31 For example, in fall 2014, it hosted an Airbnb Open, a conference to “inspire hosts and teach them about making guests feel at home.” The conference ended with a day of community service to reinforce core values.32 Tactics such as these—from “challenges” like the Superhost program to meetups and events—can be used to reinforce cultural norms and reenergize workers around your purpose.

What digital technologies or other tools do we need to extend our culture?

Digital technologies offer an array of tools that can enable leaders to share up-to-the-minute information, get instant feedback, and analyze data in real time. Leaders can and should leverage these tools not only to drive collaboration and connectivity, but also to understand the employee experience and its evolution. But don’t limit yourself to just the digital tools. Third-party co-working spaces—such as WeWork, Regus, Spaces (which Regus operates), RocketSpace, LiquidSpace, and a host of city-specific others—can be used to create communities and meeting places where virtual workers, whether on or off the balance sheet, can connect live. An influx of large companies are renting these co-working spaces for employees to create connection points and appeal to a different type of worker.33

As its Menlo Park headquarters grows and its use of other locations and virtual work expands, Facebook is finding ways to effectively use technology to extend its campus culture. The company regularly pulses employees to gather data on their perspectives on culture and engagement. It also has implemented its own product, the collaboration platform Workplace by Facebook, to enable “two-way communication for all of us, CEO to intern, no matter where you are. It connects us, and supports our culture, across the company and around the world,” according to Facebook executive Monica Adractas. (For more information, see sidebar, “Sustaining culture: Facebook’s approach.”)

Next steps

Leaders intent on extending their organizational cultures past office walls and balance sheets can consider the following steps:

Identify your alternative workforce populations with data. Take an inventory to understand where, precisely, your employees lay within these four populations, to understand how much you need to prioritize thinking about a shared culture and where to focus. Utilize data analytics to determine the percentage of workers in each segment as well as forecast future alternative workforce opportunities. Then review your strategies for how these populations may evolve in the future to ensure your strategy for maintaining a consistent culture remains relevant.

Utilize the choice cascade to intentionally create a positive culture across workforce segments. Creating consistent cultural experiences requires an intentional strategy for engaging all worker segments. Just as marketers seek to engage customers under a shared brand experience, albeit through different mechanisms, employers likewise can use the choice cascade to create positive worker experiences under a shared employer brand.

Empower leaders to create a positive organizational culture. Commit to supporting the organization’s culture across all levels of leadership. Sustaining a positive culture typically requires great commitment and efforts across all levels. Empower leaders and managers to help workers feel valued and part of a larger effort toward making a difference. This can fuel all employees’ sense of meaning and purpose, regardless of employment type.

An organization’s culture can help boost its performance—but to deliver its full potential, culture should extend to all types of workers, not just traditional employees. Given the current and anticipated growth in the off-balance-sheet workforce and in the number of individuals working off-campus, leaders should think about how they can include these workers in their efforts to create and sustain a positive organizational culture. Business leaders who are prepared to directly address this imperative will likely have more success in maintaining a culture that enables their strategy.

Sustaining culture: Facebook’s approach

At Facebook, all executives are accountable for strengthening its culture. That includes Monica Adractas, director, Workplace by Facebook. Facebook is using Workplace internally not just to enable collaboration, but to help cultivate the Facebook culture as the company experiences exponential growth. In this interview, Adractas shares her perspectives on Facebook’s strategy for maintaining a shared culture in the constantly evolving digital landscape.

Deloitte Review: What role does Facebook’s culture play in attracting, motivating, and retaining talent?

Monica Adractas: A recent study found that more than one-third of current students who will soon enter the workforce want to change the world by inventing something. A good idea or invention can change the world—but all good ideas and inventions come from people. Your team is the foundation for everything you do. So a strong, clear mission can fuel a company’s work. It also serves as the unifying force that connects everyone’s role in the company to a specific purpose. This allows leaders to guide their teams to the work that makes the company better. It also helps to propel employees to think beyond their individual roles and more about how they can contribute to something bigger. So, at Facebook we believe that connecting the world takes every one of us. We can’t make the world more open and connected by ourselves. Each one of us is a valued contributor to our mission. And we empower our community by building products that connect people and create positive social impact.

DR: In the future, do you expect Facebook’s mission to be more or less important in your efforts to attract, motivate, and retain talent? Why?

MA: We know that building an open and connected world starts with building an open and connected company. Our mission will always fuel our work as a company, and we’re only 1 percent done. We look for builders—people who have proven, by rolling up their sleeves and making a direct impact, that they’re the best at what they do. Focus on impact is one of our core values, and when we’re interviewing people, we seek to understand how they’ve made an impact in the past and the impact that they want to make in the future.

DR: What tangible practices does Facebook put in place to connect everyone to the organization’s culture?

MA: Everybody owns the culture at Facebook. That starts on your first day with our orientation and onboarding, where you learn about our core values: Be bold, move fast, focus on impact, and build social value. Additionally, Design Camp is a two-week-long orientation for all designers entering Facebook. During these weeks, designers can expect to attend prototyping workshops, hear from design leaders, and get to know members of the team.

Another key aspect of Facebook that is central to the success of our values is small teams. Small teams allow us to focus on high-impact projects, moving fast and being bold. Our hackathons are a Facebook tradition and fun event that encourages building and solving complex problems. The only rule of a hackathon is that you can’t work on anything that is part of your regular job. Hackathons are about new ideas. They are about great ideas coming from anywhere in the organization.

DR: What are some examples of employees or leaders putting Facebook’s core values into everyday action?

MA: Mark [Zuckerberg] recently laid out his vision for building a global community, which is truly the most powerful example of this. We help people do what they do best. We’re a strengths-based company, which means we’re focused on designing roles, teams, and an organization that help people do work they’re naturally great at and love doing. People perform better if they’re doing work that fits their strengths, and we spend time working with people to shape their experience around the interaction between what people love, what they’re great at, and what Facebook needs. Another example is possibly one of our boldest moves—the development of Aquila, a solar-powered, unmanned airplane that will bring affordable Internet to people in the hardest-to-reach places. Equally important to what it will achieve, Aquila embodies the notion that to make progress on your mission—in our case, to connect the world—sometimes you need to do something totally new and outside your comfort zone.

DR: What is your strategy for sustaining Facebook’s culture as you continue to grow beyond Menlo Park?

MA: Because everybody owns the culture at Facebook, as we grow, every single employee carries our culture with them. All of our locations offer opportunities to work on meaningful projects and create real impact. We have a mission that unites us, to connect the world—but we have a culture that celebrates individuality and being your authentic self. We aim, daily, to personalize the experience of working at Facebook. We do this through gathering data: We can’t guess what 17,000 people want, so we constantly ask them and iterate based on their feedback. We created a collaboration platform—Workplace by Facebook, launched in October of last year and now being used worldwide—to fully enable two-way communication for all of us, CEO to intern, no matter where you are. It connects us and supports our culture, across the company and around the world. We work hard to make sure everyone at Facebook has access to as much information as possible about every part of the company so they can make the best decisions and have the greatest impact.

DR: How do employees engage and collaborate onsite and virtually?

MA: For onsite workers, our workspaces are designed to be open and promote close collaboration with people and their teams. You frequently see people up, moving around, and talking to each other as a result of the way our offices were very intentionally designed. For virtual workers, as you would imagine, we use our own product, Workplace by Facebook, in a number of ways to connect and collaborate, whether in the office or on the go. Our teams can share information with the entire company—offices, teams, or projects; onboard new employees; and discover important things we are interested in about the company, such as financial results or product updates to Facebook or Instagram. We also found that using Workplace is a great way to test new ideas, features, and products; it gives us access to a large focus group—our entire global employee base of tens of thousands.