AI goes physical: Navigating the convergence of AI and robotics

Powered by artificial intelligence, traditional robots are becoming adaptive machines that can operate in and learn from complex environments, unlocking safety and precision gains

Robots powered by physical AI are no longer confined to research labs or factory floors. They’re inspecting power grids, assisting in surgery, navigating city streets, and working alongside humans in warehouses. The transition from prototype to production is happening now.

Physical AI refers to artificial intelligence systems that enable machines to autonomously perceive, understand, reason about, and interact with the physical world in real time. These capabilities show up in robots, vehicles, simulations, and sensor systems. Unlike traditional robots that follow preprogrammed instructions, physical AI systems perceive their environment, learn from experience, and adapt their behavior based on real-time data. Automation alone doesn’t make them revolutionary; rather, it’s their capacity to bridge the gap between digital intelligence and the physical world.

In the nascent but rapidly evolving category of robots, physical AI turns robots into adaptive, learning machines that can operate in complex, unpredictable environments. The combination of AI, mobility, and physical agency enables robots to move through environments, perform tasks, and interact with the world in ways that fundamentally differ from enhanced appliances. Embodied in robotic systems, physical AI is quite literally on the move.

Today, AI-enabled drones, autonomous vehicles, and other robots are becoming increasingly common, particularly in smart warehousing and supply chain operations. The industry, regulatory bodies, and potential adopters are working to break down barriers that hinder the deployment of solutions at scale. As organizations overcome these challenges, AI-enabled robots will likely transition from niche to mainstream adoption. Eventually, we’ll witness physical AI’s next evolutionary leap: the arrival of humanoid robots that can navigate human spaces with unprecedented capability.

From prototype to production

Unlike traditional AI systems that operate solely in digital environments, physical AI systems integrate sensory input, spatial understanding, and decision-making capabilities, enabling machines to adapt and respond to three-dimensional environments and physical dynamics. They rely on a blend of neural graphics, synthetic data generation, physics-based simulation, and advanced AI reasoning. Training approaches such as reinforcement learning and imitation learning enable these systems to master principles like gravity and friction in virtual environments before being deployed in the real world.

Robots are only one embodiment of physical AI. It also encompasses smart spaces that use fixed cameras and computer vision to optimize operations in factories and warehouses, digital twin simulations that enable virtual testing and optimization of physical systems, and sensor-based AI systems that help human teams manage complex physical environments without requiring robotic manipulation.

Whereas traditional robots follow set instructions, physical AI systems perceive their environment, learn from experience, and adapt their behavior based on real-time data and changing conditions. They manipulate objects, navigate unpredictable spaces, and make split-second decisions with real-world implications. Robot dogs process acoustic signatures to detect equipment failures before they become catastrophic. Factory robots recalculate their routes when production schedules shift mid-operation. Autonomous vehicles use sensor data to spot cyclists sooner than human drivers. Delivery drones adjust their flight paths as wind conditions change. What makes these systems revolutionary isn’t just task automation but their capacity to perceive, reason, and adapt, which enables them to bridge the gap between digital intelligence and the physical world.1

Tech advancements drive physical AI–robotics integration

Physical AI is ready for mainstream deployment because of the convergence of several technologies that impact how robots perceive their environment, process information, and execute actions in real time.

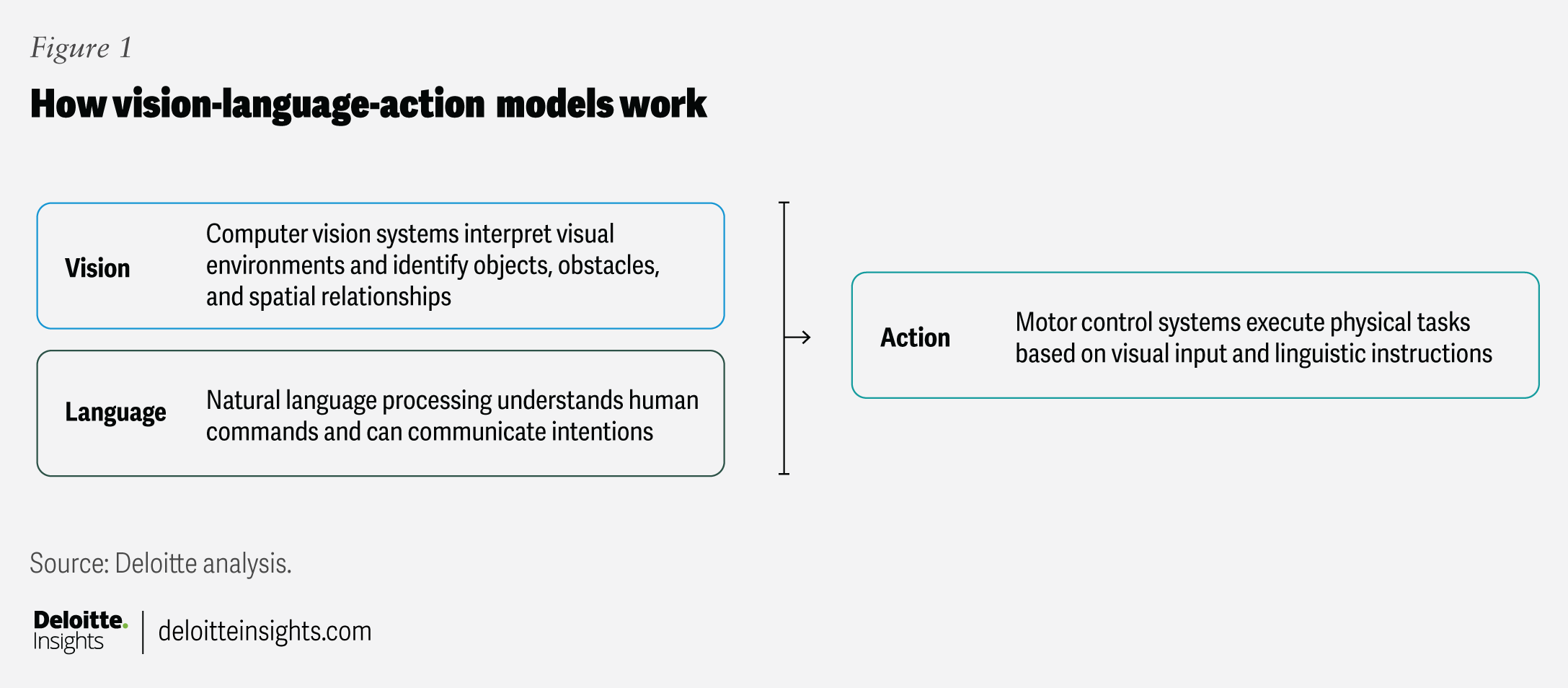

Vision-language-action models. Physical AI adopts training methods from large language models (LLMs) while incorporating data that describes the physical world. Multimodal vision-language-action (VLA) models integrate computer vision, natural language processing, and motor control.2 Like the human brain, VLA models help robots interpret their surroundings and select appropriate actions (figure 1).

Onboard computing and processing. Neural processing units—specialized processors optimized for edge computing—enable low-latency, energy-efficient, real-time AI processing directly on robots. Onboard capability allows physical AI systems to run LLMs and VLA models, process high-speed sensor data, and make split-second, safety-critical decisions without cloud dependency—essential for autonomous vehicles, industrial robotics, and remote surgery.3 It can also transform robots from isolated machines into autonomous systems that can share knowledge and coordinate actions across intelligent networks.

Robotics advancements have made robots more accessible and capable:4

- Computer vision for “seeing” and understanding surroundings

- Sensors for capturing information such as sound, light, temperature, and touch

- Actuators for movement, inspired by human muscles

- Spatial computing for navigating 3D environments

- Improved batteries that enable longer operation without frequent recharging

Training and learning. In reinforcement learning, robots develop sophisticated behaviors through trial and error by receiving rewards or penalties. In imitation learning, robots mimic expert demonstrations. Both approaches can be applied in simulated environments or in the physical world with real hardware.5 A blend of these techniques, starting with simulation-based reinforcement training and then fine-tuning with targeted physical demonstrations, can create continuous learning loops. This helps robots continue to improve by feeding real-world data back into their training policies and simulation spaces.6

Compelling economics boost industrial adoption

As technology advances, costs have been coming down, and many real-world applications have emerged.

Advanced manufacturing infrastructure now supports the production of complex robotics and physical AI systems at enterprise scale. This means that physical AI robots can now be produced with the reliability and quality control of smartphones or cars, making them practical for everyday industrial use.

Component commoditization and open-source development are reducing entry costs for physical AI systems. However, because these robots need advanced AI chips and processors, they remain more expensive than traditional industrial robots. For now, this cost gap is likely to persist, even as overall prices gradually decline.

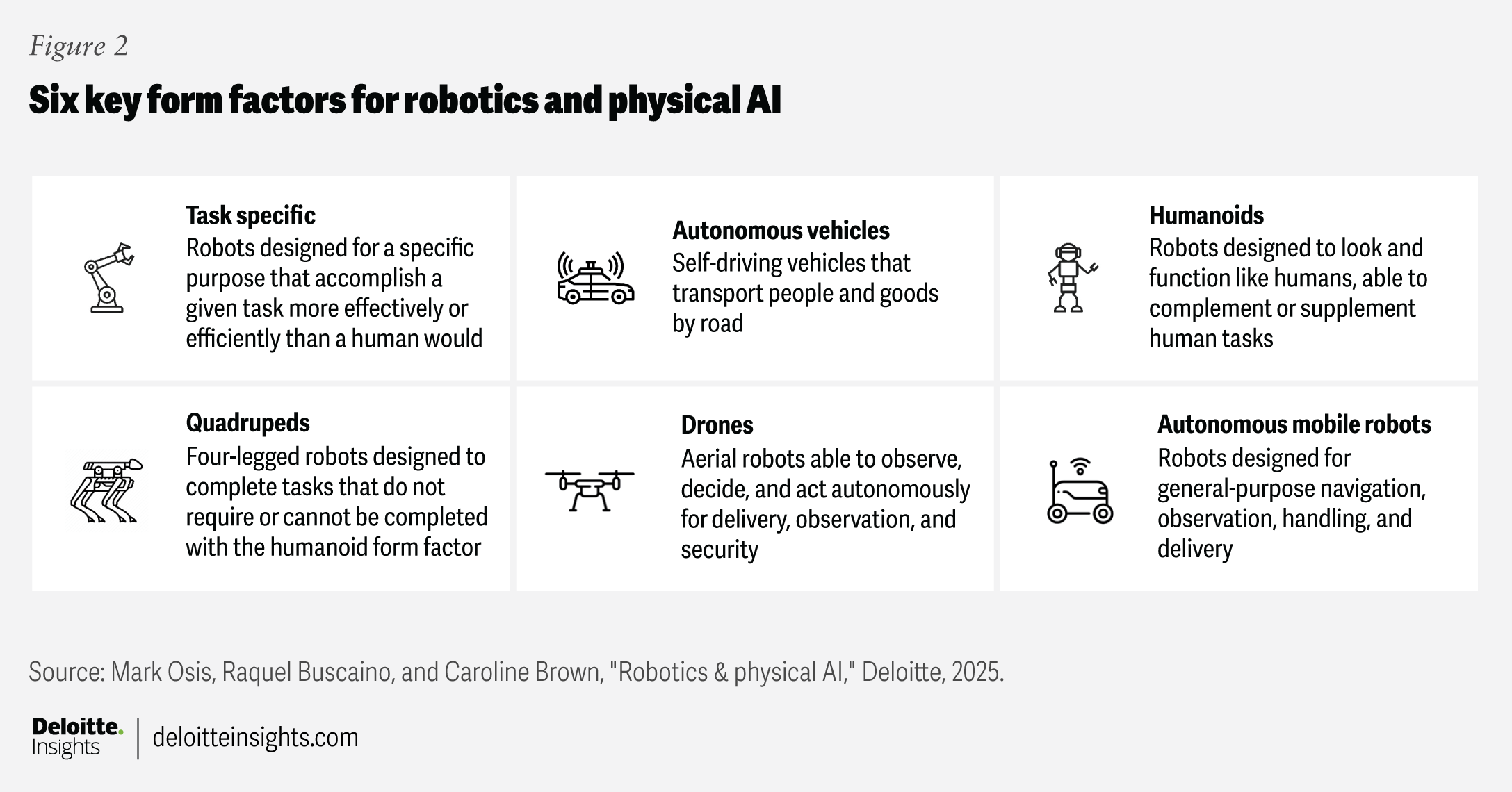

These economics are driving the adoption of physical AI and robotics in select use cases. Autonomous vehicles and drones are the most visible robotic form factors (figure 2). Waymo’s robotaxi service has completed over 10 million paid rides, while Aurora Innovation has launched the first commercial self-driving truck service with regular freight deliveries between Dallas and Houston.7

AI-enabled drones are fundamentally changing consumer expectations around speed and convenience, while also serving as powerful commercial tools. Equipped with advanced cameras and sensors, drones now manage warehouse inventory autonomously by navigating between shelves and scanning products with barcode and QR code readers.8

In the enterprise, warehousing and supply chain operations are the earliest adopters of physical AI robotic systems, likely due to labor market pressures.9

Many organizations now use these systems at scale. For example, Amazon recently deployed its millionth robot, part of a diverse fleet working alongside humans.10 Its DeepFleet AI model coordinates the movement of this massive robot army across the entire fulfillment network, which Amazon reports will improve robot fleet travel efficiency by 10%.11

Similarly, BMW is integrating AI automation into its factories globally. In one novel deployment, BMW uses autonomous vehicle technology—assisted by sensors, digital mapping, and motion planners—to enable newly built cars to drive themselves from the assembly line, through testing, to the factory’s finishing area, all without human assistance.12

The physical AI inflection point

As technologies advance and converge, costs decrease, and viable use cases emerge, physical AI–driven robots are poised to transition from niche to mainstream adoption—provided that technical, operational, and societal challenges can be overcome.

Breaking through implementation barriers

As organizations seek to scale physical AI, they’re encountering a set of complex, interrelated implementation challenges. The technology works, but making it work at scale requires solving problems that span technical, operational, and regulatory domains. Organizations that tackle these challenges head-on will define the next wave of deployment.

Training and learning. Simulation environments offer critical advantages in speed, safety, and scalability, but there’s a persistent gap between simulated and real-world performance caused by approximated physics models.13 “Visual images in simulated environments are pretty good, but the real world has nuances that look different,” says Ayanna Howard, dean of the College of Engineering at The Ohio State University. “A robot might learn to grab something in simulation, but when it enters physical space, it’s not a one-to-one match.”14 (See the sidebar for the full Q&A.)

Advances in physics engines, synthetic data generation, and approaches that blend virtual training with real-world applications should help organizations achieve the quality of physical training at the scale and safety of simulation.

The human factor: Ayanna Howard on physical AI and the future of robotics

Ayanna Howard is the dean of the College of Engineering at The Ohio State University and a prominent roboticist and advocate for AI safety and alignment. Previously, she was a senior robotics researcher at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and later chaired Georgia Tech’s School of Interactive Computing and founded the Human-Automation Systems Lab. Watch the interview.

Q: What technology challenges are holding back progress in physical AI and robotics?

A: One of the fundamental challenges is that the physical world is inherently dynamic. I can walk into my office every day, but there’s always some difference—maybe someone vacuumed, moved things around, or my computer doesn’t boot up. The question is, how do you simulate all these variations so robots can learn to adapt, walk, lift, and interact with uncertainty the way humans do? You can’t just practice endlessly in the real world because you’ll break things.

There’s also a hardware limitation I paraphrase as the “manipulation-to-physical-body ratio.” Some humans can lift their own weight or more, but conventional robots—even heavy ones—often can’t lift half their weight due to actuator limitations. They don’t have muscles like we do to offset rigid actuation, which limits what they can interact with and move.

Finally, there’s the real-time processing challenge. Large language models and vision-language models typically function in what I call “human time”: We're ok waiting a second or two for a response. But if a robot is walking and needs to make a decision, a one- or two-second delay means it drops something, crashes, or potentially hurts someone. We’re getting better at real-time processing, but we’re not quite there yet.

Q: You’ve done extensive research on trust and overtrust in AI systems. Can you explain how both extremes pose challenges?

A: It turns out that the difference between stated trust and behavioral trust is significant. In other words, people often say they don’t trust AI, but if you ask whether they use a phone or computer, or even leave their house, guess what? They’re using AI.

My research on overtrust focuses on behaviors, not what people say. We’ve conducted studies where people interact with robotic systems that were programmed to make mistakes. When surveyed, participants said they didn’t trust the systems because they had seen them make errors. But when we analyzed their actual behaviors, we saw something different: Their actions showed they did trust the robot.

With physical embodiments of AI, this behavioral overtrust becomes dangerous because these robots apply physical forces in the environment. When they do things, the consequences can be irreversible. With today’s AI, you still need human actuation for most tasks, though agentic AI is starting to change that landscape.

Q: What are the most critical research areas that need investment?

A: Learning in physical spaces without causing harm. We still need to figure out how to translate simulation to the physical world safely. Visual images in simulated environments are pretty good, but the real world has nuances that look different. A robot might learn to grab something in simulation, but when it enters physical space, it’s not a one-to-one match.

In research, robots do adapt after moving from simulation to physical environments, but they learn around tasks, not holistic environmental interactions. They might learn to grasp balls on different surfaces with varying friction coefficients. But they’re not learning how close to get to people in a mall or on a college campus while juggling those same grasped balls based on simulated social interactions. That kind of comprehensive environmental adaptation doesn’t exist yet.

Q: Do you have any hot takes that go against conventional wisdom?

A: I fundamentally believe there should always be a human in the loop somewhere. Always. And I’m a roboticist saying this. It doesn’t ensure safety 100%, but it helps mitigate overtrust. Maybe it’s the CEO doing annual reviews of the robots. Without that feedback loop, this can get away from us.

Trustworthy AI and safety. The smallest error rates can have cascading effects in physical systems, potentially leading to production waste, product defects, equipment damage, or safety incidents. If AI systems hallucinate, errors could be perpetuated and amplified across entire production runs, creating compounding downstream effects on costs and operations.

AI-powered machines can behave unpredictably even after extensive safety testing. The stakes rise significantly in public spaces, where autonomous systems must navigate unpredictable human behavior. To scale physical AI systems across various industries, comprehensive safety strategies that integrate regulatory compliance, risk assessments, and continuous monitoring are necessary.15

Regulatory environment. Companies must navigate overlapping and sometimes contradictory requirements across jurisdictions.16 As robots move from controlled factory environments into public spaces, regulatory bodies are likely to develop new frameworks for safety certification, liability, and operational oversight.

Data management. Organizations must capture and manage massive amounts of sensor data, 3D environmental models, and real-time information. High-fidelity digital twins of physical assets are essential for effective training and deployment, requiring extensive data on physical characteristics, object properties, and interactions. Organizations will also need to integrate multimodal data from disparate sources, ensure data security, and manage data infrastructure costs.

Human acceptance. While most workers are generally comfortable with predictable, rule-based robots, physical AI systems that learn and adapt introduce new uncertainties, especially worries about job displacement. However, experts predict that most roles will evolve toward collaboration rather than replacement.17 The goal is to create environments where robots handle repetitive or dangerous tasks while humans focus on creative problem-solving and complex decision-making.

Cybersecurity vulnerabilities. As discussed in “The AI dilemma,” physical AI systems create new attack surfaces that bridge digital and physical domains. Connected fleets increase cyber risks, with vulnerabilities potentially leading to unauthorized access, data breaches, or even malicious robot control. The stakes are even higher when security breaches can affect physical safety and operational continuity.

Robot fleet orchestration. As physical AI systems mature, organizations will increasingly deploy heterogeneous fleets of robots, autonomous vehicles, and AI agents from multiple vendors, each with proprietary protocols. This creates interoperability challenges that can lead to accidents, downtime, system congestion, and operational inefficiency.18 Autonomous fleet management and orchestration systems can help resolve these issues.

Over the coming 18 to 24 months, resolving these foundational issues will likely enable physical AI and robotics to expand beyond traditional industries. Warehousing and logistics may have served as physical AI’s proving ground, but sector boundaries do not limit the technology.

Crumbling sector boundaries

As leading organizations across the public and private sectors are laying the groundwork for physical AI at scale, adoption is accelerating exponentially. Applications are emerging wherever physical AI solves real problems.

In health care, a sector facing global staffing shortages, medical technology companies are developing AI-driven robotic surgery and digital imaging devices. GE HealthCare is building autonomous X-ray and ultrasound systems with robotic arms and machine vision technologies. Other medtech companies are designing intelligent robotic assistants that can help with patient care and automate surgical tasks.19

Restaurants are also deploying robots to help address labor shortages. Sidewalk-crawling delivery robots travel at pedestrian speeds; inside restaurants, robots handle tasks like flipping burgers and preparing salads, while service robots seat customers and serve food.

Naturgy Energy Group, a Spanish multinational natural gas and electrical energy utilities company, currently uses drones for inspection purposes. Rafael Blesa, Naturgy’s chief data officer, envisions an expanded role for physical AI as the technology hardens, particularly in dangerous field operations involving high voltage or open gas pipes. “Many operations related to grid maintenance could be performed by robots in the long term,” he explains. “My expectation is that in three to four years, we’ll have robots performing physical operations, which could save lives.”20

Similarly, the city of Cincinnati is using AI-powered drones to autonomously inspect bridge structures and road surfaces, reducing costs, keeping human inspectors out of hazardous situations, and condensing months of analysis into minutes. “This type of technology is going to be the nuts and bolts of what’s going to allow [mayors] to do their jobs better and provide better information, decisions, and cost efficiencies for their constituents,” said Cincinnati’s mayor, Aftab Pureval.21

In 2024, the city of Detroit launched a free autonomous shuttle service designed for seniors and people with disabilities whose mobility was severely limited by traditional transit systems. Known as Accessibili-D, the self-driving vehicles were equipped with wheelchair accessibility and a trained safety operator. Three autonomous vehicles operated within an 11-square-mile section of Detroit, offering 110 different stops.22

Regardless of the sector, these deployments share a common characteristic: They augment human capabilities in situations where safety, precision, or accessibility are most critical.

Humanoid robots and beyond

We’ve all seen the viral videos of humanoid robots with their fluid, not-quite-human-but-pretty-darn-close movements. They’re the most compelling robotic form factor, not because they have the most efficient design, but because our world is built for human bodies. This means they can navigate existing infrastructure—doorways, staircases, factory floors, and home kitchens—without costly modifications to accommodate specialized robotic systems.23

“People are very compliant in how they interact with the world and constantly make contact with their environment. That’s very hard for a commercial robot,” says Jonathan Hurst, a robotics researcher at Oregon State University and cofounder of Agility Robotics. “Typically, robots are very position-controlled devices. They’re good for things like CNC machining [precision manufacturing requiring exact, repeatable positioning] or spot welding, but they’re not good for assembly, manipulation, or locomotion in nonstructured spaces.”24 (See sidebar for the full Q&A.)

Several companies have developed and continue to refine bipedal robots with more precise finger control. With the recent introduction of chain-of-thought reasoning abilities comparable to human cognition, the technological foundation continues to advance.25

During the next decade, the intersection of agentic AI systems with physical AI robotic systems will result in robots whose “brains” are agentic AIs. Robots of all form factors should increasingly be able to adapt to new environments, plan multistep tasks, recover from failure, and operate under uncertainty. The impact of this technology convergence will be particularly profound for humanoid robots.

Instead of custom robotics for each domain, more general agentic modules may be reused across warehouses, homes, health care, agriculture, and other areas. Agentic humanoids could one day function as assistants, coworkers, or health care aides with more intuitive interaction, reasoning, and negotiation capabilities.

Mass adoption of humanoids is likely several years away. Still, UBS estimates that by 2035, there will be 2 million humanoids in the workplace, a number it expects to increase to 300 million by 2050. The firm estimates the total addressable market for these robots will reach between US$30 billion and US$50 billion by 2035 and climb to between US$1.4 trillion and US$1.7 trillion by 2050.26

Enterprise applications like warehousing and logistics remain the proving ground for humanoid deployment, driven by labor shortages. BMW is testing humanoid robots at its South Carolina factory for tasks requiring dexterity that traditional industrial robots lack: precision manipulation, complex gripping, and two-handed coordination.27 For similar reasons, humanoids could play a role in health care. One health care company is testing humanoids in rehabilitation centers to assist therapists by guiding patients through exercises and providing weight support.28

The larger long-term opportunity lies in consumer markets, where the vision extends to comprehensive household tasks such as elderly and disability care, cleaning and maintenance, meal preparation, and laundry. The Bank of America Institute projects that the material costs of a humanoid robot will fall from around US$35,000 in 2025 to between US$13,000 and US$17,000 per unit in the next decade, and Goldman Sachs reports that humanoid manufacturing costs dropped 40% between 2023 and 2024.29

From the lab to the real world: Jonathan Hurst on humanoid robots

Jonathan Hurst is a robotics professor at Oregon State University and cofounder of the school’s Robotics Institute, where his research focuses on legged locomotion. He’s also the cofounder and chief robot officer of Agility Robotics, which develops and deploys humanoid robots that operate alongside human workers in commercial applications. Watch the interview.

Q: Were you trying to solve a specific problem by building a robot with a humanoid form factor?

A: We wanted to make machines that move like animals or people and that could also exist in human spaces. People are very compliant in how they interact with the world and constantly make contact with their environment. That’s very hard for a commercial robot. Typically, robots are very position-controlled devices. They’re good for things like CNC machining [precision manufacturing requiring exact, repeatable positioning] or spot welding, but they’re not good for assembly, manipulation, or locomotion in nonstructured spaces.

With our robot, we’ve gotten pretty close to a normal human-like leg configuration—bipedal, upright torso, bimanual. The most important thing is that each of these features has a purpose. We are capturing the function that underlies that form.

Q: How did you figure out what the humanoid could do?

A: From the beginning, we aimed to build a human-centric, multipurpose robot. We looked at hundreds of use cases. It turned out that the simple task of lifting and moving bins and totes is a good match for the technology. This task requires something with a narrow footprint to operate in hallways, go through doors, and be in human spaces. It needs to be able to lift something heavy—like 25 kilograms—to the top of a two-meter shelf.

For this, you need something that’s dynamically stable—a robot that maintains its balance while in motion. A statically stable base will just tip over if you’re trying to lift these things. Therefore, a bipedal pair of legs is the most effective way to be dynamically stable and not fall.

That’s the starting point. From there, we got it to be bimanual because, to pick up big things, you need a grasp on both sides. You need a reachable workspace to pick something off the ground and lift it up high, and an upright torso to do that, so it’s a particularly good match for the technology.

That’s very hard to do with existing automation. There is a fair amount of flexibility needed because all the workflows are distinctive. Different types of totes go to different places, for example. You stack the totes, palletize them, put them on conveyor belts, or take them off AMRs [autonomous model robots]. This kind of variety makes it hard for traditional automation, yet it’s still quite structured. You might say semi-structured. It’s in an industrial environment that’s well-controlled and process-automated, which makes it a really good starting point for a humanoid.

Q: How can the use of humanoids scale?

A: The market for humanoids is going to be twice the size of the automotive industry in 25 years. There’s a lot of scaling to be done to get to that point because that’s millions of robots. Today, there are only hundreds of robots.

There is a massive market for the functionally safe humanoid—the robot that doesn’t have to be confined to its own work cell. That’s when you’ll be able to start deploying robots in the thousands. How do you support them in the field? How do you have your robot fleet management software work over all the unique bandwidth limitations and everything else? That’s a hard thing to do in robotics, but it can be done. Waymo has deployed what are basically robots on the roads, so it’s definitely feasible. It’s not like something has to be invented, but the organization has to execute really, really capably to do that. That’s the journey we’re on, once the robot is safe enough to warrant the scale.

Beyond humanoids?

Humanoid robots capture public imagination with their familiar bipedal form. Where do we go from there?

In terms of physical form factors, boundary-pushing engineers are increasingly experimenting with machines that blur biological lines. Imagine robots powered by living mushroom tissue, those that mimic movements using rat muscle tissue, or machines that can transition between solid and liquid states using magnetic fields. In innovative laboratories today, scientists are integrating living organisms into mechanical systems, developing robots that can navigate complex environments through multiple modes of locomotion, and creating machines that adapt their physical form to match the task.30

Quantum robotics—the combination of quantum computing and AI-powered robotics—also holds promise, though it’s still in the very early stages. Superposition, entanglement, quantum algorithms, and other quantum computing principles could allow robots to operate at speeds that are impossible for today’s binary computers.31 Quantum algorithms are expected to improve processing, navigation, decision-making, and fleet coordination, while quantum sensors will enhance perception and interaction.32

Useful quantum robots are expected to be many decades away. Hardware immaturity, integration challenges, and the extreme sensitivity of quantum states are just a few of the challenges that must be solved before quantum computing can be widely deployed.33

Humanoid butlers are at least a decade away, and exotic form factors and quantum capabilities remain largely experimental. But they represent a fundamental shift in how we think about robotics. As these breakthrough technologies graduate from the lab to the enterprise to the home, the field of robotics is moving beyond simply automating human tasks toward creating entirely new categories of machines.