AI, demographic shifts, and agility: Preparing for the next workforce evolution

A Deloitte survey reveals how AI and human collaboration can help close talent gaps, speed upskilling, and transfer knowledge as demographic changes reshape the workforce

Kyle Forrest

Brad Kreit

Abha Kulkarni

Roxana Corduneanu

Sue Cantrell

The workforce appears to be undergoing a significant transformation. Fewer people are entering the job market;1 one recent study found that the number of high school graduates in the United States was expected to peak in 2025 and then decline throughout the next decade, primarily due to a long-term drop in birth rates.2 Meanwhile, a significant number of experienced workers are reaching retirement age, with estimates suggesting that by 2030, 1 in 6 people globally will be over the age of 60.3

These demographic shifts are shrinking the pool of available talent in mature economies, leading to potential labor shortages and a widening skills and experience gap that could make it difficult for organizations, especially in construction, hospitality, and other industries, to find and retain the talent they need to drive growth.4

At the same time, advances in artificial intelligence are reshaping how some work gets done. Routine tasks are being automated, and the traditional structure of work is evolving in real time. Deloitte’s TMT predictions team anticipates that by 2027, 50% of firms that currently use generative AI will at least be piloting agentic AI, which could create opportunities to increase the productivity of individual workers but also raise questions about how to optimize human and machine teams.5

How can organizations prepare for and respond to the pressures of a shrinking labor supply and rapid technological change? Many are already exploring ways to augment human and machine collaboration in the workplace as a potential solution. But to help unlock this value, organizations should understand how technology weaves into the fabric of work and where the opportunities and risks lie.

For example, organizations can use AI to bridge knowledge and experience gaps, upskill workers, and enable new, value-added capabilities—but which activities should not be automated? Which should remain clearly managed and driven by humans, and how should organizations make these decisions?

To better understand how organizations could use AI to augment the changing shape of the workforce, Deloitte surveyed more than 11,000 workers across 17 countries, exploring how they use AI and emerging technologies their preferred collaboration strategies, and how they build skills (see methodology).

Our survey highlights four key opportunities for organizations to integrate AI and human capital to address workforce challenges: enabling human–machine teaming, experimenting with agentic technology while keeping humans on the loop in workflows, using AI to strengthen skill development, and improving knowledge and wisdom transfer through AI tools. For organizations, identifying which tasks may benefit most from automation—and which tasks benefit from human involvement—could be an important factor in designing work in the coming years. By identifying where workers currently find value in AI and where collaboration with colleagues is most beneficial, organizations can optimize their technology investments to help drive short-term efficiency and productivity gains while building the skills and talent pipeline needed for the long term6.

Demographic changes get real

The demographic recomposition of the workforce may have begun with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, when workforce participation rates dropped significantly and have yet to fully recover. One analysis estimated that, as of 2024, five million fewer people were working than projected prior to the pandemic.7 This shift is driven by increased retirements and fewer entrants into the labor market. A Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta analysis found that nearly two million Americans reached retirement age in 2022, compared to just 40,000 Americans entering “prime working age,” commonly defined as ages 25 to 54, that year.8 AI may be contributing to the limited entry of entry-level workers into the labor market, with 67% of respondents in a 2024 Deloitte survey believing that AI could reduce the availability of entry-level roles, making it difficult for them to join the workforce.9

In the United States, workforce participation is already in decline and is projected to drop further from 63% in 2023 to 61% in 2033 as the population continues to age and retire.10 Not only could these demographic changes contribute to worker and skill shortages, but they may also put organizations at risk of losing institutional knowledge and experience as more tenured workers leave the workforce.

While the number of new entrants to the workforce continues to decline in some regions, rapid growth is anticipated in other parts of the world. By 2030, one projection estimates that two-thirds of new entrants to the workforce will reside in Sub-Saharan Africa,11 and by 2040, Africa is expected to have the largest workforce globally, surpassing India and China.12 Although these populations may contribute to remote work, they are unlikely to fill gaps in mature economies for jobs that require an on-the-ground presence, like manufacturing, construction, health care, and other front-line roles.

A mismatch between skills and market demand could be exacerbating these demographic-related hiring challenges. A Lightcast analysis found that 9 of the 10 most in-demand roles only require a high school education. Still, around two-thirds of US high school graduates immediately enroll in college, creating an oversupply of candidates for some roles and a lack of candidates for others.13 Coupled with AI’s impact on entry-level opportunities, this may help explain why entry-level workers in fields like computer science are struggling more to find jobs than in previous years.14 At the same time, demand for workers in skilled trades is intensifying: A manufacturing executive recently estimated that they receive only one qualified applicant for every 20 US job openings.15

This skill gap appears to be leading to some unexpected outcomes. For example, one high school junior told The Wall Street Journal that he felt “like I’m an athlete getting all this attention from all these pro teams,” as companies are already recruiting him despite being more than a year away from graduation—not for sports, but because he is enrolled in a welding program, a field facing a growing talent shortage.16 This trend not only highlights current shortages but may also foreshadow a much larger shift in how early-career workers are rethinking their approach to work.

Unlocking workforce potential through better human–machine collaboration

As more tasks can potentially be delegated to agentic technology, organizations will have the opportunity to redefine human collaboration, teaming, and work. To do so, they may need to adopt a more holistic approach that integrates human and machine workflows into a unified effort, while also implementing targeted strategies to address critical skill and experience gaps. In the following sections, we explore opportunities for organizations to embrace this holistic approach to augment the changing shape of the workforce.

Opportunity 1: Most workers want a mix of human and AI collaboration

In recent years, AI tools have evolved from simply automating tasks to working more collaboratively with humans in decision-making and coaching roles.17 This trend is likely to continue: Deloitte’s TMT Predictions 2025 expects that by 2027, half of companies using generative AI will have launched agentic AI applications capable of performing complex work with limited oversight.18 Organizations that understand these technological opportunities and apply them to address skill and experience gaps may uncover unexpected benefits—provided they strike the right balance between human and AI collaboration.

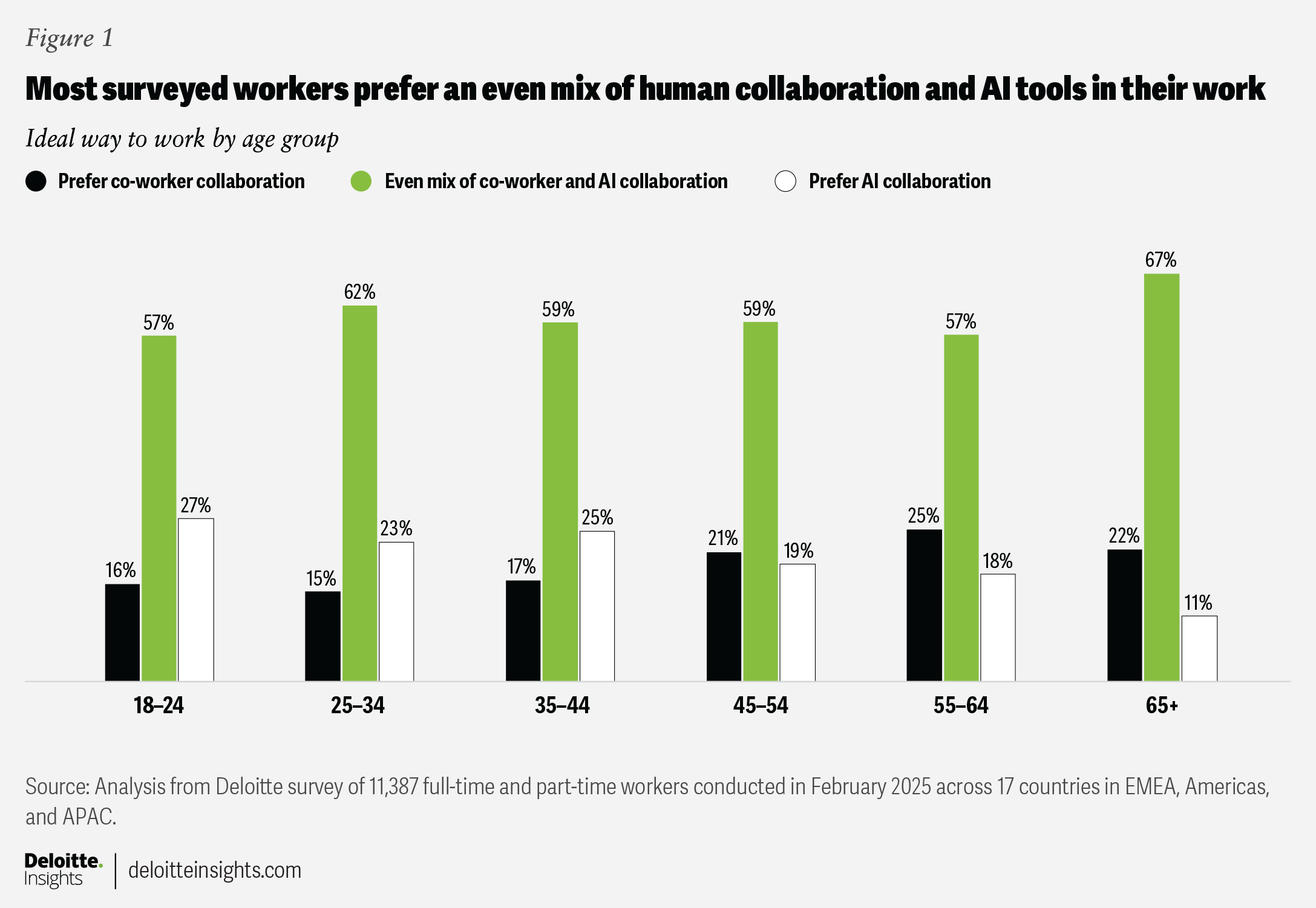

Most workers in our survey expressed a preference for combining technological tools with human interaction as part of their work. While workers ages18 to 44 report a stronger preference than others for using only AI tools, and older workers report a stronger preference for human-only collaboration, the vast majority across all age groups prefer an even mix (figure 1). Workers ages 65 and older seem to be the most open to blending AI tools with human teamwork, but they report lower interest in working only with AI, suggesting that this cohort is taking advantage of emerging technology while continuing to value human interaction

Harnessing these opportunities may require organizations to reimagine how they think about teaming, collaboration, and AI. One researcher studying AI’s impact on human collaboration notes that, as this technology matures, “AI sometimes functions more like a teammate than a tool.” This shift may call for organizations to “reconsider team structures, training programs, and even traditional boundaries between specialties.”19

Some organizations are already starting to redefine these boundaries, including at the executive level. Pharmaceutical company Moderna recently merged its human resources and information technology executive roles into a single chief people and digital technology officer position as part of its broader digital transformation and growth strategy.20 Moderna is also exploring ways to link multiple AI agents to enhance workflows between digital tools and human workers—and even using digital agents to proactively identify potential sources of tension between senior leaders so human workers can prevent conflict before it happens.21 These approaches highlight the potential for integrating human capital and AI planning in order to strengthen organizational processes and growth.

Key takeaways

To facilitate better human and machine collaboration, leaders can consider:

- Defining guidelines for collaborating with AI and workers. Analysis shows that most workers—across all age groups—prefer a mix of human and AI collaboration. Organizations should consider establishing clear frameworks reflecting these preferences to maximize adoption and value.

- Redesigning teams to include AI as a teammate. AI is evolving from a tool to a teammate. This shift may involve rethinking roles, training, and cross-functional boundaries. Organizations should consider restructuring team dynamics to enable AI–human teaming across functions to enhance agility and innovation.

- Defining task boundaries between humans and AI. As AI becomes more capable, it’s important to decide which tasks are best done by people and which by AI. Using AI for faster delivery, repetitive tasks, and data-heavy work could help free up time for humans to work on strategic tasks that need judgment, empathy, or complex problem-solving. Clear guidelines can help workers collaborate with peers and AI effectively.

Opportunity 2: Human oversight still matters, but AI wins on speed

Even as workers and organizations are learning to integrate gen AI into their workflows, advances in agentic AI have the potential to increase performance by taking on a wide array of tasks with limited human oversight.

Worker preferences will likely evolve alongside these tools.22 Experimenting with and investing in agentic technology offers an opportunity to understand how it might coevolve with worker expectations. In the near term, Deloitte’s TMT Predictions suggests that organizations can maximize the value of agentic AI by keeping humans “on the loop” in workflows involving digital agents.23 This approach differs from keeping humans “in the loop,” as it allows them to oversee and manage digital agents similarly to how they might manage a junior employee.

Organizations can also assess tasks across a spectrum of automation to identify which can be delegated to technology and which tasks require human oversight.24 This perspective could help organizations prioritize technology investments for tasks well-suited to agentic AI while directing human capital investments to areas where human oversight is most critical.

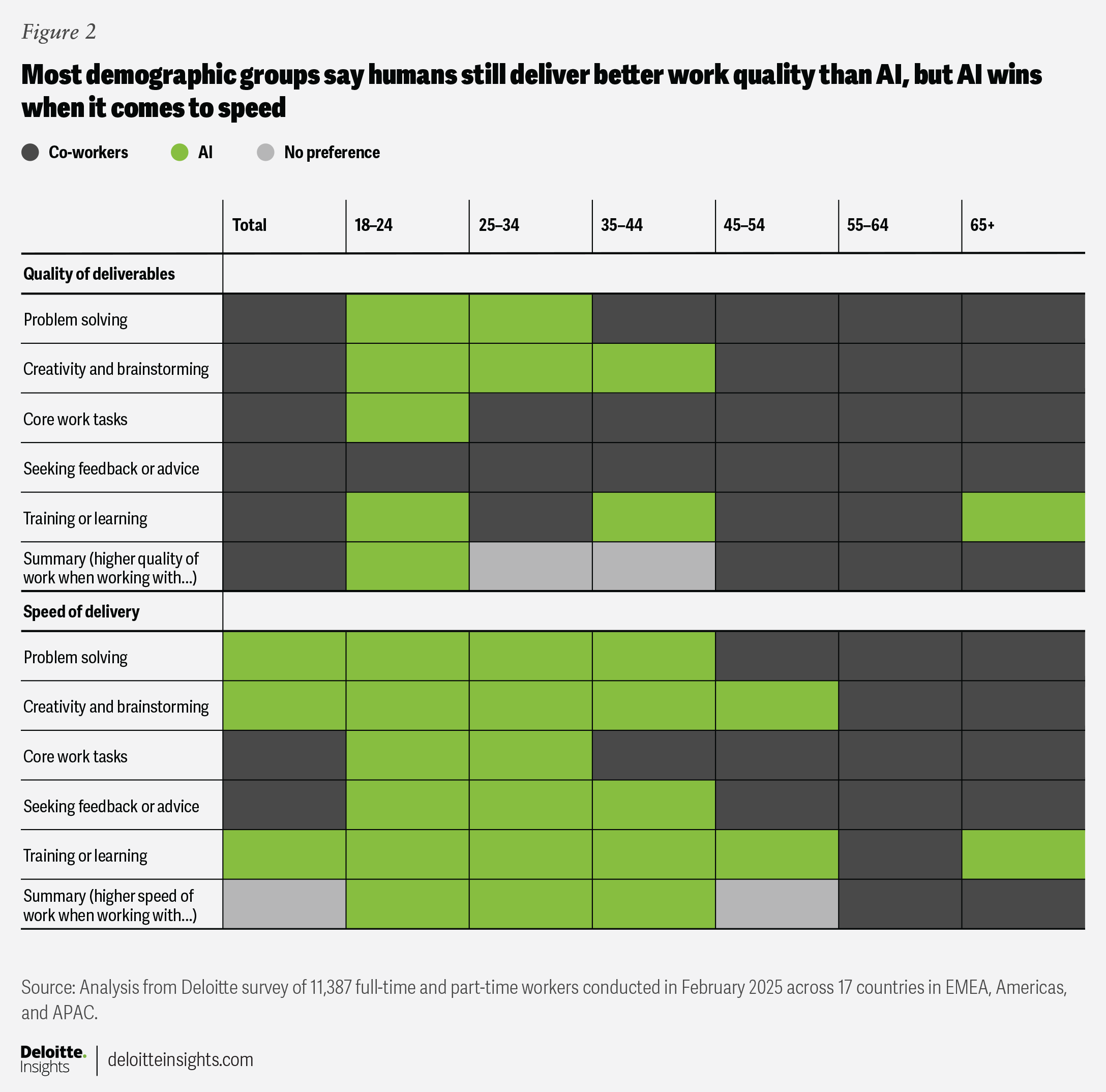

Our survey highlights the tasks respondents see as most in need of human oversight. While workers across all age groups expressed a general preference for collaborating with both AI and human colleagues, notable differences emerged between age cohorts regarding who delivers better quality and speed—humans or AI (figure 2).

In general, respondents rated their work quality higher when working with human colleagues. Respondents across all age groups reported receiving higher-quality feedback from human colleagues compared to AI. Aside from the youngest workers, most preferred peer collaboration over AI for core work tasks. These findings suggest that while workers recognize the value of AI tools, they still see benefits to human collaboration—especially for work requiring in-depth knowledge.

However, when it comes to speed of delivery, the picture shifts. Across several tasks—especially problem solving, creativity, and training—respondents from younger age groups (ages 18 to 44) were more likely to say that AI helps them deliver faster. The youngest workers (ages 18 to 24) rated AI higher on speed in nearly every task type. These findings seem to reinforce the perception that AI tools excel in efficiency, even if they don’t yet match humans in quality or nuance.

This reflects a key tension at the heart of AI integration: the tradeoff between speed and quality. While AI is valued for its ability to deliver faster results, workers across generations remain cautious about using it for work requiring human-centric skills. Monitoring how these preferences change over time will be key as technology evolves, particularly as AI-native workers entering the workforce may have stronger preferences for using these tools compared to those who entered the workforce before the advent of AI.25 Investing in AI technologies may not only enhance current workforce productivity, but it could also attract talent eager to benefit from the latest advances.26

Our survey findings also suggest that there is scope to better train and develop AI tools and agents to help workers with core tasks, creativity, brainstorming, training, and seeking feedback or advice. Respondents’ preferences for working with AI were also influenced by several other factors, including their preparedness and perception of AI’s utility. Workers who felt more prepared to use AI at work were more likely to say that AI outperforms humans in speed. Similarly, those who found AI more helpful in their work were more inclined to rate AI higher in both quality and speed. These findings emphasize the importance of investing in AI literacy and skill development programs as part of a holistic approach to technology and talent development.27

Key takeaways

Leaders can consider the following actions to prioritize human oversight of agentic AI as it becomes more embedded in organizational workflows:

- Establishing clear boundaries for automation around tradeoffs between efficiency and quality. Updating AI usage guidelines to distinguish between activities where AI can be used for speed and efficiency, and those that require deliberate human oversight or governance, can help create these boundaries.

- Monitoring workforce preferences around human and AI collaboration. Surveys and feedback can be useful tools for tracking worker preferences. Surveyed workers rate humans higher on quality, especially for core tasks, but younger surveyed workers (ages 18 to 24) say AI delivers faster results in nearly every area. Defining where and how to use AI for work could become critical for organizations in the future, especially as digital natives majorly comprise the workforce.

- Keeping humans “on the loop” instead of just “in the loop.” As agentic AI takes on more complex tasks at work, organizations could shift from direct control to supervisory oversight on these tasks. Treating AI like a junior team member—monitored, guided, and corrected when needed—can help enable efficiency without sacrificing accountability.

- Investing in AI literacy and skill development. Respondents who feel more prepared to use AI and understand its capabilities and limitations rate it higher in both speed and quality. Prioritizing training programs that build AI fluency can help increase adoption and impact.

Opportunity 3: AI can be an upskilling engine—especially for entry-level workers

Organizations are increasingly linking together multiple agentic systems, taking agents designed to handle specific tasks and combining them to create larger workflows. These new workflows can help boost productivity across job levels and free up time for workers to focus on other tasks.

However, while agentic technology may offer efficiencies, it also raises questions around skill development, especially for early-career workers. It will likely be important for organizations to invest not only in technology but also in developing a robust talent pipeline.

Deloitte’s 2025 Human Capital Trends found that two-thirds of surveyed hiring managers and executives believe entry-level hires are underprepared, with lack of experience being the primary weakness. One risk of treating AI development separately from human capital development is that automation may reduce opportunities for on-the-job training. Automating tasks traditionally performed by entry-level workers, such as taking and distributing meeting notes, may create short-term efficiencies but may limit on-the-job training and other tools organizations have traditionally used to upskill early-career workers.28 Deloitte research suggests that the rise of AI could be contributing to the difficulty workers face in finding entry-level jobs.29

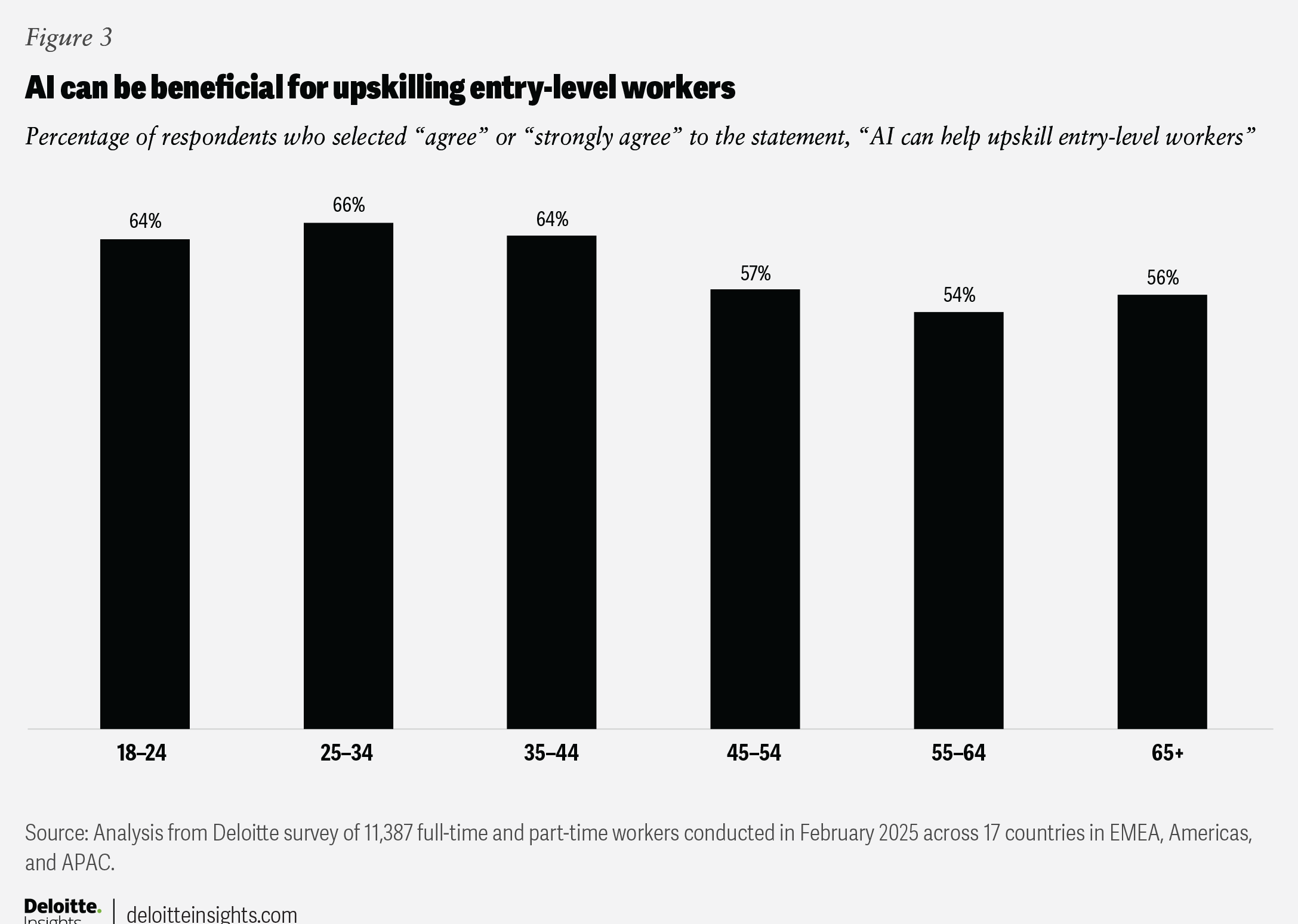

To manage this dynamic, organizations can leverage AI to accelerate skill development for early-career workers. Sixty-one percent of respondents to our survey believe that AI can support upskilling opportunities for entry-level workers, with respondents between the ages of 25 and 34 years being the most likely (66%) to agree. Research by the National Bureau of Economic Research shows that gen AI can be particularly beneficial for lower-skilled workers, offering real-time support and coaching to help them learn faster.30 It also suggests that early-career workers are more likely to embrace AI as a tool for skill development.

The benefits of AI upskilling extend beyond early-career workers. As our study revealed, workers across all age cohorts, including those nearing retirement age, prefer collaborating with a mix of human co-workers and AI. But while 67% of respondents over the age of 65, in our survey, say they prefer working with both AI and human co-workers, only 42% agree that they are prepared to use AI at work (compared to 54% of workers of all ages), suggesting there may be opportunities to improve AI upskilling for this age group.

Key takeaways

To help workers across all career stages adapt and thrive in an AI-driven workplace, leaders can consider the following actions:

- Balancing automation with on-the-job training and learning opportunities. This can help workers, especially early-career workers, still have opportunities for hands-on learning and skill development. While agentic AI boosts efficiency, automating tasks like note-taking may limit hands-on training for workers. Leaders should ensure automation doesn’t displace critical on-the-job learning, especially for entry-level roles.

- Providing real-time coaching through AI tools. Sixty-one percent of surveyed workers believe AI can help upskill entry-level talent, especially those between the ages of 25 and 34. Using AI to deliver real-time feedback, support, and learning pathways can help accelerate talent development, especially for early-career workers.

- Upskilling workers for AI collaboration. Upskilling can help workers feel more prepared to use AI effectively in their roles. Although a high percentage of surveyed workers ages 65 and older prefer working with both AI and humans, only 42% feel prepared to use AI, possibly indicating a need for building AI fluency in tenured workers. Tailoring AI training can help workers stay productive and confident in evolving roles.

- Redesigning onboarding programs to encourage AI use from day one. To prepare new hires for AI-integrated workflows, organizations should embed AI literacy into onboarding. Starting on day one can help normalize collaboration with AI and build long-term digital capability.

Opportunity 4: AI can accelerate knowledge transfer and mentorship

Some organizations are already successfully using current technologies to help match workers across job levels and skill profiles to support upskilling. For example, global financial services company HSBC uses a digital platform to match workers to projects and peer mentors based on their current skills as well as those they want to develop. A veteran employee with expertise in a particular domain can be algorithmically paired with a younger worker seeking that skill, allowing tacit knowledge transfer through real projects. This approach encourages cross-generational networking and on-the-job learning. HSBC reports that these skill-based opportunities have helped break down silos, engage experienced staff as teachers and coaches, and enable younger workers to learn from seasoned experts.31

Similarly, Salesforce’s Career Connect AI tool empowers internal employees to explore potential career pathways by evaluating their current skill sets and surfacing internal roles and learning programs they may not have previously considered. For example, one employee—without any prior sales background—was matched to a role in sales enablement due to relevant experience in change management and coaching. This AI-driven recommendation led to internal transition and career advancement that might have otherwise gone unrealized.32

As more workers continue to age out of the workforce and retire, leveraging AI to help newer entrants upskill and take on more complex tasks will likely be important to addressing potential skill shortages.

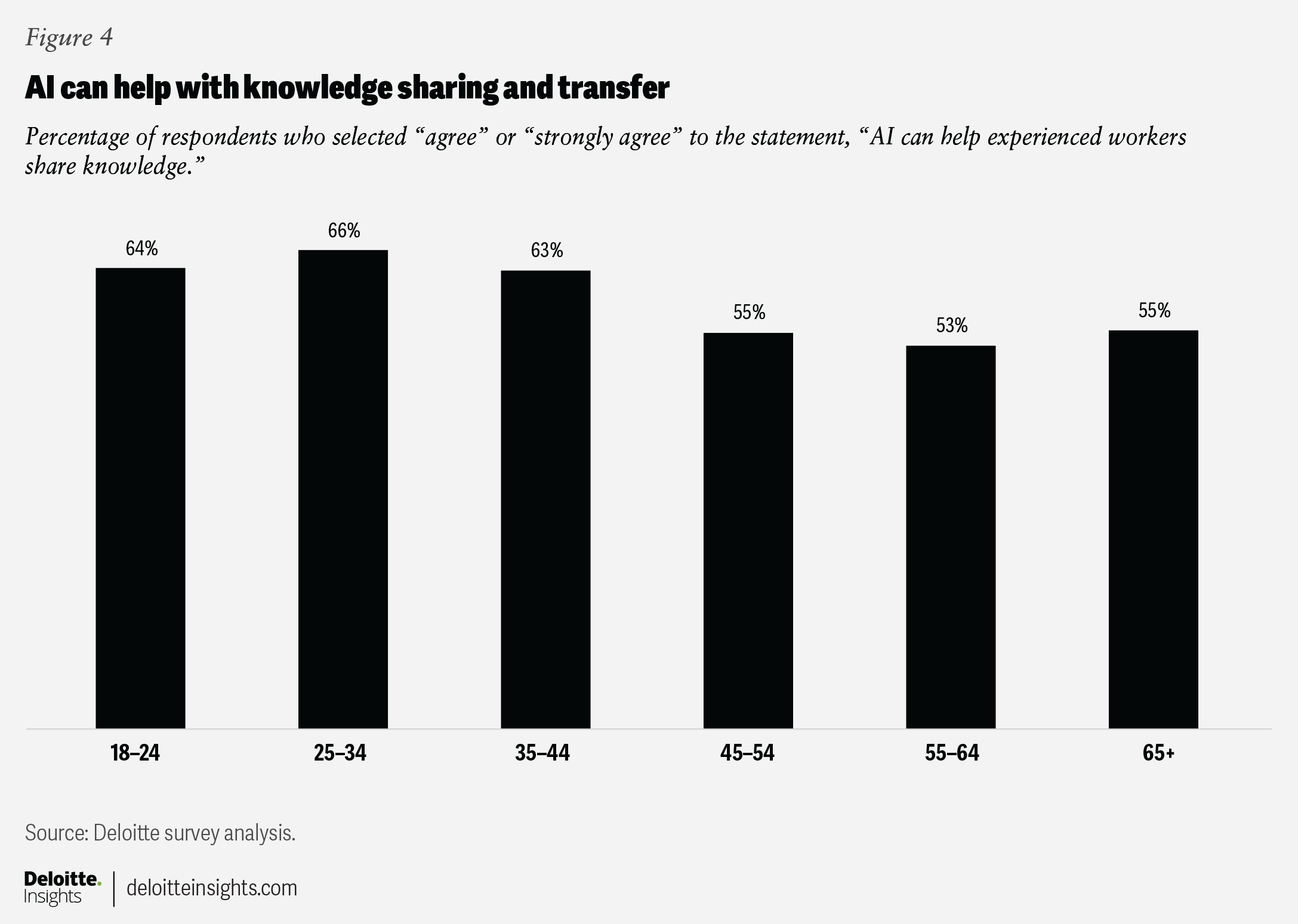

Our survey findings also highlight some less obvious opportunities to invest in AI for skill development. For example, 60% of respondents in our survey say that AI can help experienced workers share knowledge and skills with the rest of the organization. While workers under the age of 45 are more likely to see this potential, a majority of respondents across all age groups agree that AI can help facilitate knowledge-sharing from experienced workers (figure 4). This interest suggests workers are excited about opportunities to use AI tools to share what they know and learn from each other.

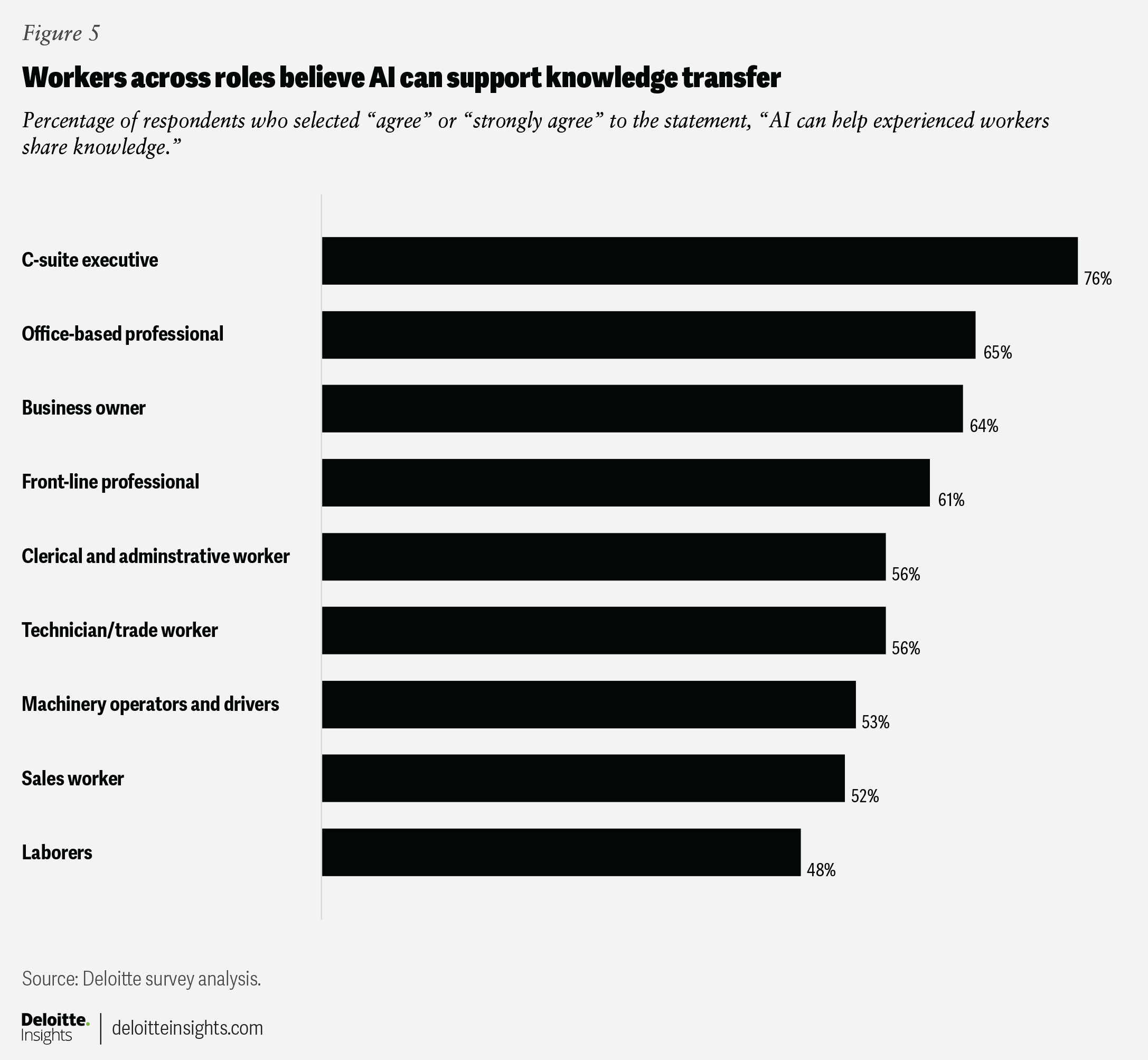

Role-based responses show more variation in respondents’ perceptions of AI’s potential for knowledge transfer. C-suite executives (76%), office workers (65%), and business owners (64%) are most likely to agree that AI can help support knowledge transfer from more experienced workers to newer ones (figure 5). However, sales workers (52%), trade workers (56%), machine operators (53%), and laborers (48%) are less likely to see AI as playing a role in knowledge transfer. Identifying barriers to knowledge transfer in these roles—especially given the demand for workers in these areas—could be especially important for organizations.

Efforts to support workers in capturing their wisdom and tacit knowledge for sharing across the organization with AI can take multiple forms, helping to bridge age and job-level gaps.

For instance, researchers found that encouraging senior physicians to collaborate with residents on new robotic surgery tools led to mutual learning, not only about the tools but also broader aspects of surgery and patient care.33 This collaboration reportedly improved overall learning, teamwork, and a shared sense of purpose, which workers age 65 and above identified in our survey as a motivator in their work.

These findings suggest that upskilling and knowledge transfer efforts don’t have to be one-way streets. Integrating AI and other new technologies can create learning opportunities that cut across traditional boundaries, strengthening the capabilities of workers at all levels of the organization.

Key takeaways

Leaders looking to support knowledge transfer and mentoring with AI tools can consider these actions:

- Using AI-driven platforms to match employees across job levels. AI platforms can base these recommendations on an employee’s current skills and desired development areas. Companies can use AI to pair workers based on current and aspirational skills, enabling mentorship and experiential learning. Embedding these platforms could help foster cross-generational collaboration.

- Implementing AI tools to help experienced workers document and share their expertise. Sixty percent of surveyed workers believe AI can support knowledge sharing, especially among those under the age of 45. Using AI tools to help experienced employees capture and transfer tacit knowledge before retirement or turnover could help organizations retain their legacy knowledge and expertise.

- Facilitating mutual learning across generations. Pairing senior employees with junior staff on projects involving new technologies can drive two-way learning. AI tools can amplify this exchange, reinforcing purpose and engagement for more experienced employees while upskilling newer ones.

Thriving in the evolving workforce

Over the next several years, questions about AI’s role will likely continue to intersect with those about workforce composition. As experienced workers retire and potentially fewer new entrants join the labor market, organizations may face a shrinking talent pool just as work demands are becoming more complex. Meanwhile, emerging technologies like generative and agentic AI could present opportunities to augment human potential and close experience gaps.

Organizations may benefit from taking a holistic approach, understanding how and when to prioritize technology investments while continuing to develop the talent, skill, and expertise their workforce needs. Those who act decisively by leveraging AI to augment their workforce could bridge widening skills gaps and labor shortages, creating adaptable, resilient organizations positioned to thrive as workforce dynamics evolve.

Methodology

Deloitte surveyed 11,387 full-time (81%) and part-time workers (19%) between February 20 and February 27, 2025. The respondents interviewed were spread across 17 countries from the EMEA region (45%), the APAC region (32%), and the Americas (24%) region. They represented a mix of age, experience levels, industries, and business functions and were asked about their use of and attitudes towards AI, motivations at work, interest in alternative work models, and retirement plans.