The divergence dynamic: How unconventional thinkers may give agentic AI an edge

The next leap in AI performance may not come from technology alone, but from teams with the cognitive range to explore alternatives, test edge cases, and imagine what models can’t

Chloe Domergue

Brenna Sniderman

Sue Cantrell

Jonathan Holdowsky

Natasha Buckley

Imagine a scenario where an artificial intelligence research lab faces a frustrating roadblock. The goal is bold: build an AI capable of orchestrating a city’s power grid more efficiently. But after months of training an agentic AI system to manage urban energy distribution, the model can optimize, but only within the familiar confines of existing strategies. More data doesn’t help. More computer power doesn’t help. The AI remains locked in variations of the obvious.

Now imagine that the breakthrough comes not from code, but conversation. A visiting behavioral ecologist asks: What if the system modeled energy like a living ecosystem rather than a utility network? It’s a metaphor most engineers wouldn’t have entertained. But it sparks new thinking, amplified by two neurodivergent analysts who push to test edge cases others dismiss. Within weeks, the lab rebuilds its simulation around ecological principles. Resilience improves significantly under stress conditions that had previously broken the system.1

While this is a hypothetical case study, it illustrates an important truth: As businesses race toward agentic AI—the next wave of machine intelligence that not only can answer questions but can also set goals, adapt, and make autonomous decisions—the real competitive advantage may not lie in bigger models or faster chips. It may lie in who is in the room, and how differently they think. Organizations that cultivate divergent thinking will likely build more resilient, trustworthy AI than those who simply invest in more computing power.

The next leap in AI—and its human challenge

Agentic AI is poised to transform enterprise life. Unlike the chatbots and co-pilots of today, agentic systems can independently decide what to do, pursue objectives over time, and coordinate across tasks. Analysts predict that by 2028, 33% of enterprise software applications will include agentic AI, compared with less than 1% in 2024.2 These systems won’t just assist—they’ll orchestrate. A procurement agent could reroute a supply chain in real time; a compliance agent could flag, freeze, and investigate suspicious transactions; a medical agent could adjust therapies minute by minute.

The allure is obvious: efficiency, speed, and scalability. But agentic AI is also complex, unpredictable, and in some cases, opaque. Building and using such systems should involve more than just technical expertise. It can benefit from imagination to design new workflows, vigilance to anticipate and recognize risks, and creativity to spot opportunities that algorithms alone can’t surface.

This is where organizations can falter. Teams trained to converge on consensus, to optimize rather than reinvent, are likely ill-suited to the messy, nonlinear work of building and using agents that operate safely and originally. What’s missing isn’t more engineering horsepower. What’s missing is difference—both in thinking style and in cognitive makeup.

Divergent thinking and neurodivergence: Two forms of difference

To understand why that difference matters, it helps to distinguish between two forms it can take: divergent thinking and neurodivergence.

Divergent thinking is a concept familiar to psychologists: the ability to generate many ideas from a single prompt, to connect the unrelated, to see alternatives where others see constraints. It’s the mental habit that underlies brainstorming, metaphor-making, and lateral problem-solving. Deloitte research includes divergent thinking as one of six specific human capabilities like curiosity and creativity that enable individuals to adapt and thrive in a world of constant technological and organizational change.3

Neurodivergence is different. It refers to the natural variations in how human brains work—including autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and other conditions. Studies suggest between 15% and 20% of people are neurodivergent.4 For decades, these differences were framed primarily as deficits. Increasingly, however, research and practice have shown that neurodivergent individuals often bring distinctive strengths: hyperfocus, anomaly detection, pattern recognition, and associative leaps.5

Together, these two forms of difference, cultivated divergent thinking and lived neurodivergence, can offer a potent antidote to the potential biases of conventional teams developing and using agentic AI systems. Divergent thinking can help create a culture where alternative ideas are welcomed; neurodivergent perspectives can inject fundamentally different ways of perceiving problems.

When these forms of difference come together, they can help shape a team that is defined not just by who is present, but by the conditions that ensure their perspectives matter. Some important characteristics of these teams may include:

- Diversity of perspectives within and across teams. Members bring different professional backgrounds, cognitive styles, and lived experiences.6

- Psychological safety. People feel free to share unpolished or unconventional ideas without fear of ridicule or penalty.7

- Openness and curiosity. Team members actively explore multiple possibilities instead of seeking a single “right answer” too quickly.8

- Constructive conflict and debate. Differing viewpoints are welcomed and used to challenge assumptions.9

- Inclusive practices. The team makes space for all voices, ensuring quieter members or those with different communication styles are heard.10

- Experimentation mindset. Learning from successes and failures is part of the culture.11

- Flexible leadership. They act as facilitators, present challenges broadly, and guide the process without constraining creativity.12

In short, a team can be more likely to think beyond convention when it combines varied inputs (diverse roles and professional backgrounds, ideas, and perspectives) with enabling conditions (safety, openness, and structure) that allow those inputs to interact productively.

Why agentic AI can benefit from them both

Resilient, trustworthy agentic AI systems will likely need more than just clean data and strong models. It can be beneficial for them to be imagined, monitored, refined, and used by people who see the world differently or are comfortable thinking differently. Here are three reasons why:

1. Creativity in framing problems. AI is boxed in by its programming. The quality of its goals and prompts shapes everything downstream. Divergent thinkers, especially neurodivergent team members accustomed to spotting unconventional angles, can help expand the design space. They may ask questions others don’t. What if energy grids worked like ecosystems? What if compliance agents cooperated like ant colonies? These leaps are where breakthroughs can begin.

2. Breadth of collaboration. As agents proliferate, they will interact with one another; for example, compliance agents talking to finance agents, or care agents coordinating with medical systems. Designing these interactions is helped by flexibility in perspective. ADHD research shows extraordinary skill in divergent ideation;13 dyslexic thinkers often excel in spatial reasoning and systems thinking.14 Such cognitive diversity can complement AI’s strengths and help compensate for vulnerabilities.

3. Rigor in quality assurance. Even the most advanced AI models can hallucinate. Neurodivergent analysts, particularly those on the autism spectrum, have been recognized for excellence in testing and error detection. Companies like Ultranauts, Auticon, and Aspiritech have built quality-assurance businesses on this principle.15 Equally, workers who are able to think differently can bring unconventional approaches to spotting inconsistencies and edge cases that traditional methods can miss, creating a complementary layer of protection against subtle system failures. These capabilities are not only useful but may be essential safeguards.

The case for diverse thinking is strong, but many organizations aren’t leveraging it

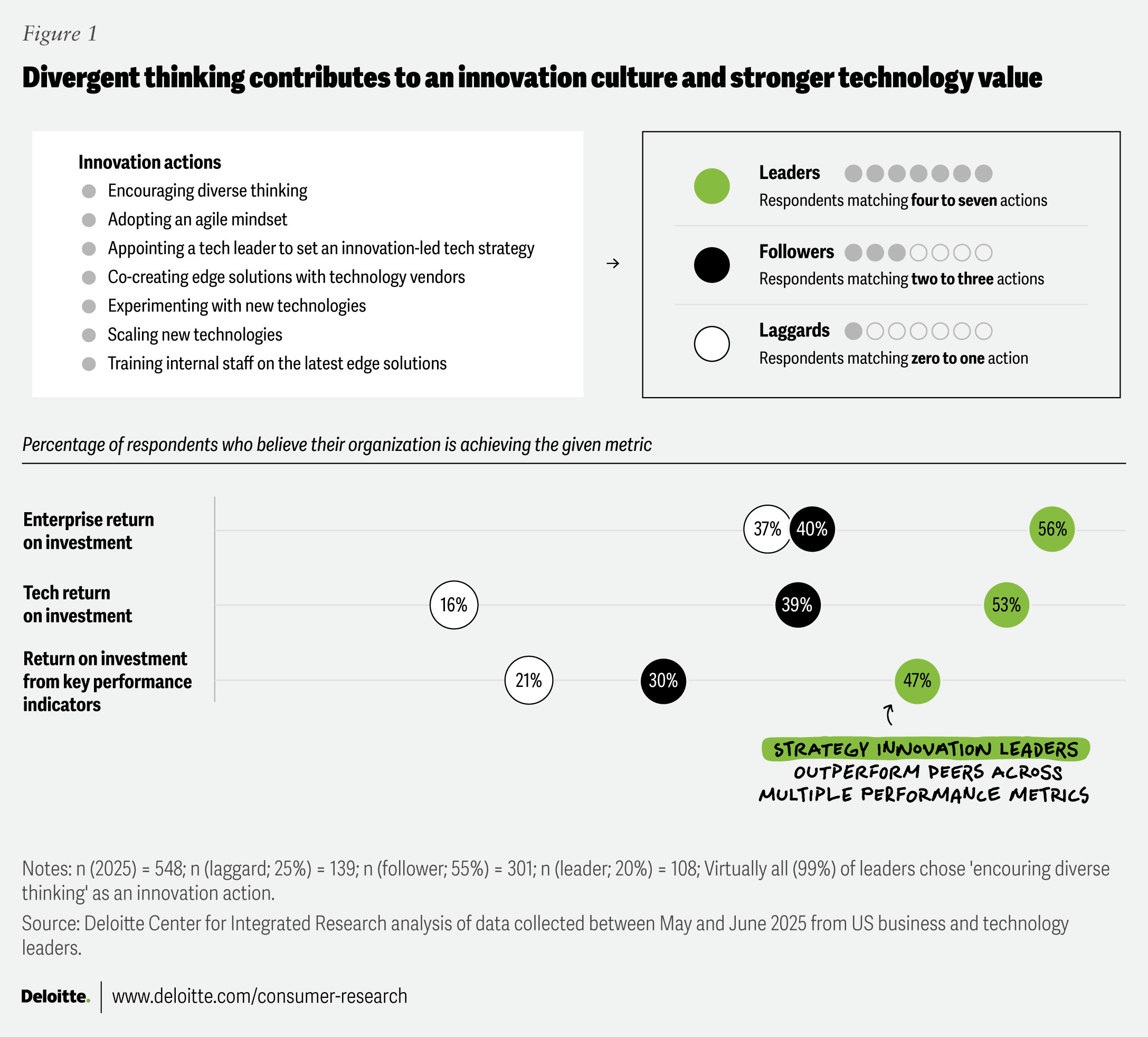

The argument for difference isn’t just theoretical. Deloitte’s 2025 survey on technology value found that organizations fostering a high degree of innovation-related attributes, including agile thinking and diverse thinking styles, outperformed peers across a variety of performance metrics, including average return on key performance indicators, technology return on investment, and return on equity (figure 1).16

Furthermore, recent Deloitte analysis of worker trust shows that trust in agentic AI is not only technical; it’s also cultural. Workers who believe their organization overlooks diversity of thought in AI design are 60 percentage points less likely to use such tools daily.17 Cognitive diversity, as it turns out, helps shape adoption in addition to innovation.

Meanwhile, corporate neurodiversity programs are demonstrating measurable returns as well. Some corporate programs have shown productivity gains of up to 140% in certain testing roles.18 Additional organizations report positive results, with neurodivergent employees uncovering errors and opportunities invisible to others.19

It’s becoming clear that diversity of thought is more than a nice-to-have. It can be a source of resilience and innovation in environments defined by volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity—the conditions in which agentic AI will likely operate.

And yet, despite the evidence, many organizations underutilize these capabilities. A recent Deloitte survey found that more than half of surveyed managers believed their teams embraced differing viewpoints, but only a third of employees agreed.20 The gap suggests that leaders overestimate how much divergent thinking actually happens.

Part of the issue could be structural. Rigid interview processes and AI-driven screening may filter out neurodivergent candidates or candidates who don’t check conventional boxes in terms of skills and job experience. Performance metrics may reward consensus and speed rather than careful dissent or unconventional ideas. Team cultures may prize the “quick win” over experimentation.

Organizations may value difference in principle, but in practice, existing processes can unintentionally starve their AI initiatives of the creativity and analytical strength those systems need to perform at their best.

What leaders can do differently

Agentic AI is not simply another productivity tool. How these systems behave and integrate will depend on the creativity of their design and usage and the vigilance of their oversight. Even as workers surveyed in Deloitte’s workforce trust research voice concerns about AI outpacing regulation (36%) and its ethical implications (35%), a quieter but equally consequential anxiety emerges: that AI could narrow human creativity.21 Addressing these concerns will likely involve not only governance, but diversity in the minds shaping the systems.

Homogenous teams that are technically brilliant but cognitively narrow can produce systems that plateau, or worse, fail in ways their designers may not have imagined. But teams that emphasize and cultivate divergent thinking and neurodivergent perspectives may be better able to see around corners. They can catch errors others miss. They may be able to imagine and orchestrate workflows others cannot. And they may be able to build agentic systems that are not only more innovative but also more trustworthy.

If agentic AI is to deliver on its promise, organizations should consider intentionally designing for cognitive difference. That could mean:

- Educating executives and managers about the strategic value of diverse thinking. Leaders can reframe traits like hyperfocus or sensory sensitivity as assets. For agentic AI teams, these traits can translate into deep focus on complex problem spaces, such as driving interoperability of agents across systems,22 detecting subtle anomalies in system behavior that may indicate vulnerability, or identifying risks and opportunities. Leveraging these strengths can improve how agentic models are designed, tested, and used amid real-world complexity.

- Creating psychological safety. This involves giving teams unstructured time and permission to explore and think differently without fear of looking unproductive or uncooperative.23 Agentic AI development and use can thrive on experimentation, where unexpected breakthroughs and use cases often emerge from trial, error, and lateral thinking. A safe environment can encourage researchers and engineers to test unconventional ideas, which can lead to more adaptive and resilient agentic systems.

- Recruiting explicitly for difference. This may include rewriting job descriptions to value cognitive diversity and adapting interview formats to reduce bias. Agentic AI can benefit from teams that mirror diverse human perspectives, as these systems are designed to operate autonomously across varied contexts. By intentionally hiring for difference, organizations can build teams that are better able to anticipate edge cases, avoid vulnerabilities, and embed inclusivity into AI behaviors.

- Redesigning workforce recognition and performance management systems. Organizations can ensure that contributions expressed through analysis, pattern detection, or testing are rewarded alongside bold presentations. In agentic AI projects, quieter forms of contributions such as identifying subtle flaws in multi-agent interactions or detecting emergent risks can be just as critical as high-profile breakthroughs. Rewarding these contributions can help ensure that innovation is grounded in rigor, not just visibility.

Thinking beyond the obvious

Agentic AI is coming fast. Within a few years, it will likely be embedded in how enterprises operate, decide, and act. If agentic AI is to earn human trust, it should mirror human variety. The more cognitively homogenous its makers, the narrower its imagination, and the thinner the trust it inspires. The question is whether agentic AI will amplify creativity. And the answer may depend less on the technology itself than on who builds it. Thinking differently—by design, and with intention—can make all the difference.