Safeguarding Medicare: Proactive care could unlock $500B in annual program savings

Deloitte research shows disease-prevention investments could boost health and longevity, help secure Medicare’s future, and cut US medical and drug spending by $2.2T a year

Andrew Davis

Neal Batra

Dr. Ken Abrams

Dr. Jay Bhatt

Dr. Kulleni Gebreyes

Chris Kottenstette

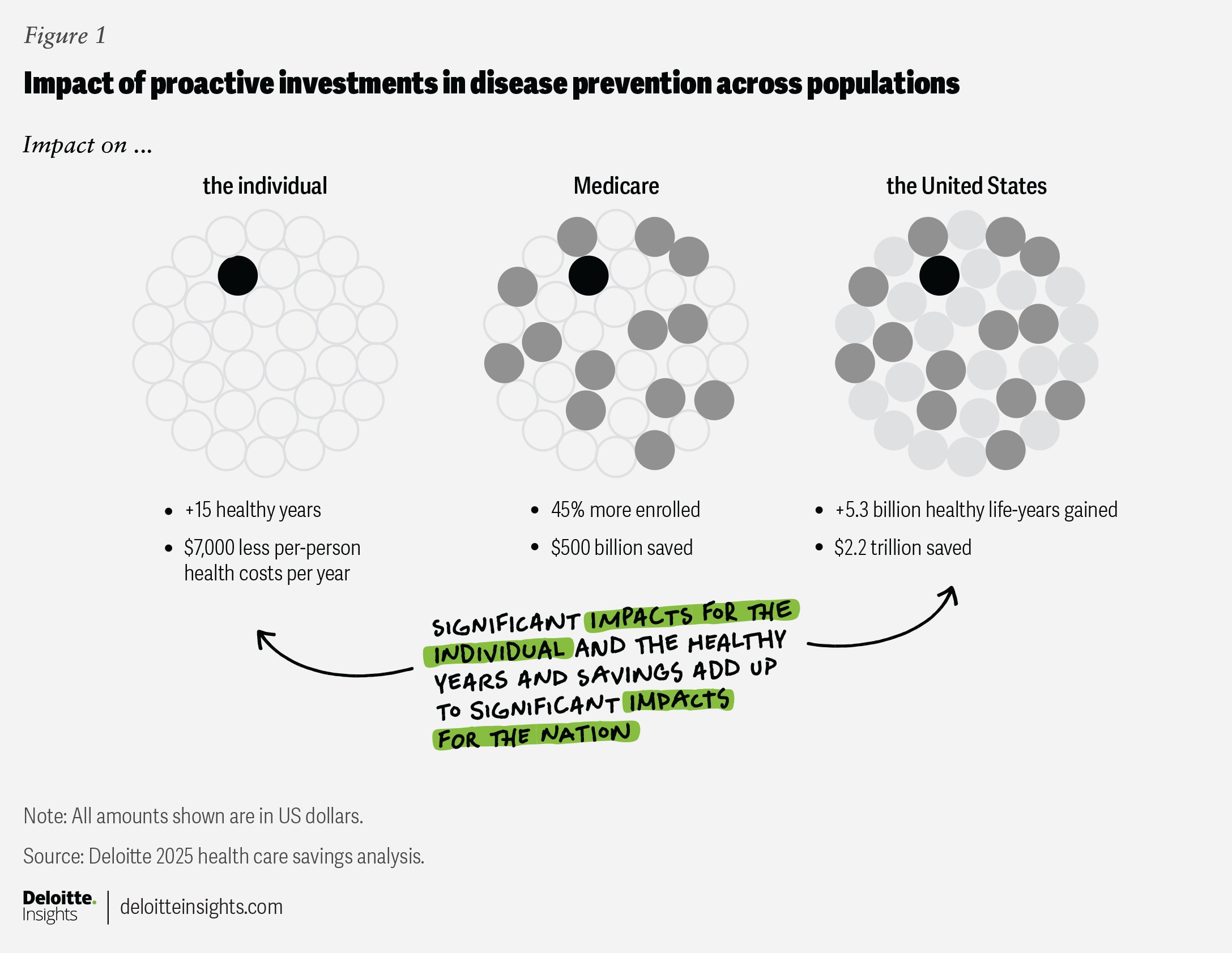

Strategic investments in disease prevention, early detection, and other proactive measures could save the US health care system up to $2.2 trillion a year by 2040—more than $7,000 per person—according to new research from Deloitte’s actuarial and health care teams. These investments could also help save Medicare more than $500 billion a year on medical and prescription drug claims, strengthen the program’s long-term financial outlook, and expand the number of years beneficiaries live in good health. Deloitte analysis suggests that lowering Medicare spending in this way could delay potential insolvency and ease the need for benefit reductions or tax increases to maintain the program as it currently exists.

Today, most US health care spending is reactive, focused on treating illnesses and conditions after they occur, while only a small portion is allocated to proactive measures such as prevention, early detection, and the promotion of overall well-being. This imbalance drives higher long-term costs and poorer health outcomes for individuals.1 However, it also creates an opportunity: Shifting resources to proactive care could dramatically reduce spending and improve quality of life for Americans.

Without change, health care costs are expected to increase by an average of 5.8% annually between 2023 and 2033. As a result, health care spending as a share of the gross domestic product is projected to grow from 17.6% to 20.3%, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).2 However, these projections are not inevitable. Deloitte’s actuarial analysis shows that investments in prevention, early detection, behavioral change, and other proactive measures could reduce overall health spending (medical and prescription drugs) by 28% in aggregate compared with current CMS projections. By 2040, per-person care costs could drop by 31%—from $23,000 to less than $16,000 (figure 1). For Medicare beneficiaries, the reduction could be more than $18,000 per year.

A collaborative multi-stakeholder initiative—including health systems, health plans, employers, and the federal government—could help slow the rise in health care spending while improving the population’s health span (the average number of healthy years between birth and death). Each stakeholder can help evaluate existing programs and funding and explore ways to better capture the value of investments in prevention.

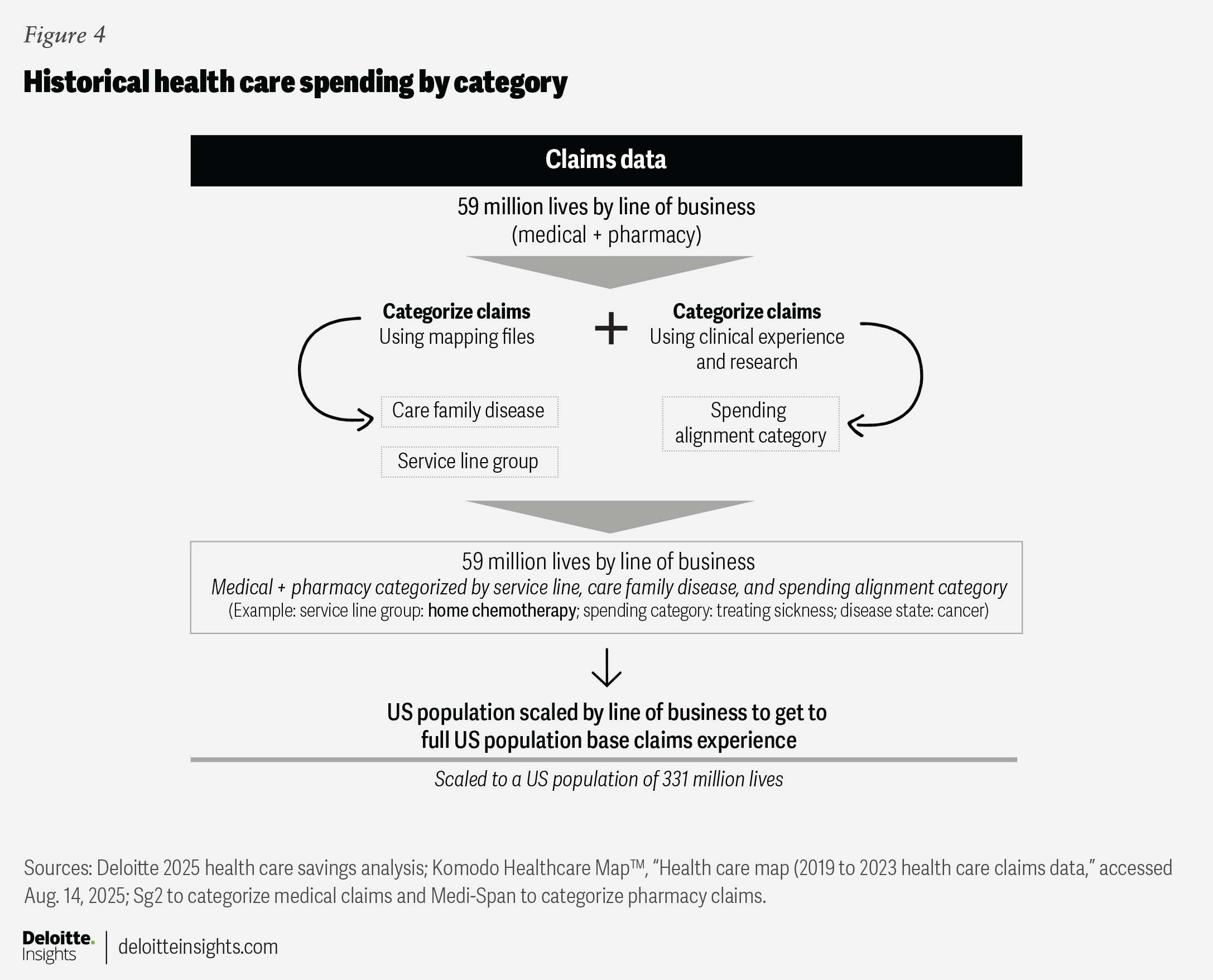

To reach these conclusions, Deloitte actuaries examined five years of medical and pharmacy claims data covering 59 million individuals, scaling the findings to represent the entire US population. Each claim was categorized by disease state and grouped into four care categories: treating conditions, managing or delaying symptoms, restoring health, and promoting health. The analysis also incorporated health and wellness-related expenses paid by consumers and government funded health-related activities to provide a comprehensive view of health care spending and potential savings (see Methodology: How Deloitte analyzed US health care spending and prevention scenarios).

Proactive care could be key to lowering US health care spending

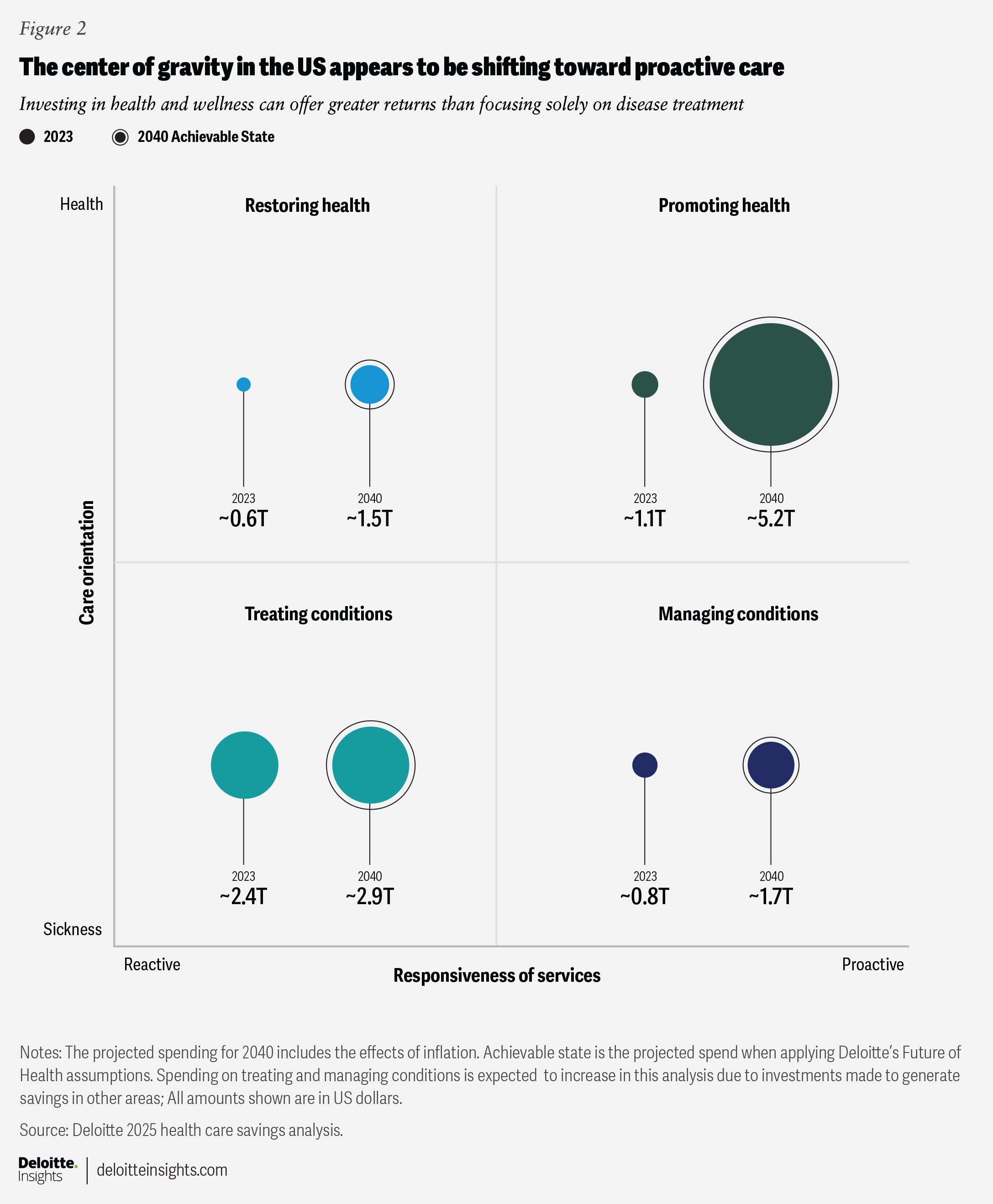

To better understand these spending patterns and clarify how dollars are allocated, we grouped all health care spending into four care categories:

- Treating conditions (reactive): This category includes claims for the treatment of illnesses, injuries, or deteriorating health. It encompasses interventions such as diagnostic procedures, surgeries, and medications such as antibiotics or chemotherapy. The team’s analysis determined that these costs make up more than 50% of total health care expenditures, totaling about $2.4 trillion annually.

- Restoring health (reactive): This category includes costs related to recovery and rehabilitation following an illness, injury, or deteriorating health. Services may include medical treatments, physical therapy, and other interventions aimed at helping individuals regain their optimal health. Restoring health comprises 12% of total health care spending, or about $604 billion annually.

- Managing or delaying symptoms (proactive): This category covers services for patients with one or more chronic conditions, focusing on preventing complications and reducing symptom severity. Treatments and interventions in this category account for about 16% of reviewed medical claims, representing roughly $758 billion per year.

- Promoting health (proactive): This category includes claims for preventive services and wellness activities provided to individuals who are in good health. The goal is to prevent future health issues and enhance quality of life and mental well-being. Promoting health represents 22% of total health spending, representing roughly $1.1 trillion per year.

A shift in spending patterns by health care category is anticipated, with a movement away from traditional treatment and a growing emphasis on the promotion of health and well-being. In this potential scenario, expenditures dedicated to promoting good health are projected to increase at an average annual rate of 10% through 2040, whereas the costs associated with treating conditions are expected to grow more modestly, at just 1% per year (figure 2).

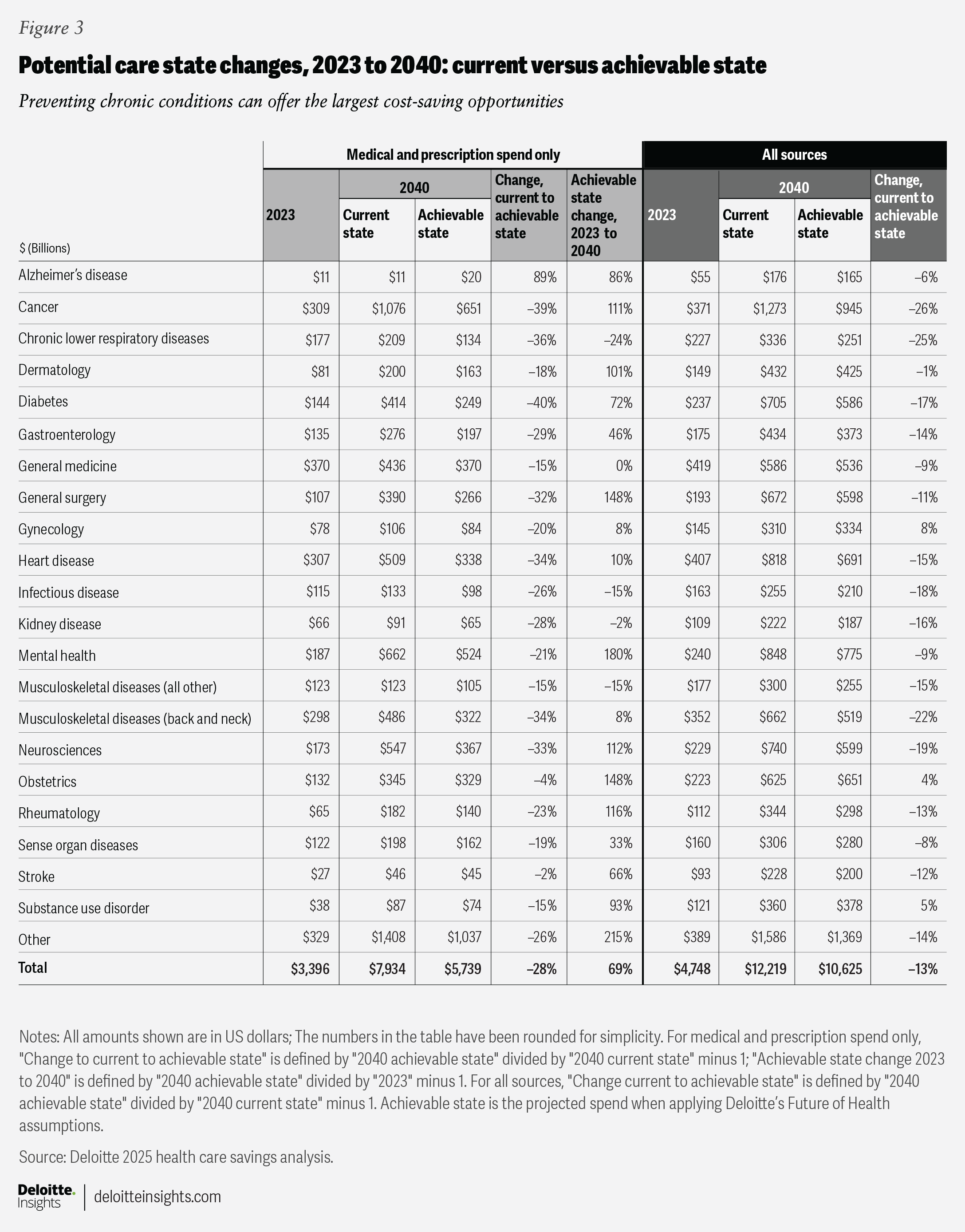

The potential benefits of proactive health care investments vary widely by disease state. For example, by 2040, baseline projections indicate that medical and pharmacy spending on cancer could reach $1.1 trillion ($1.3 trillion including health and wellness-related expenses paid by consumers and government-funded health-related activities). However, Deloitte’s Future of HealthTM framework suggests that a more proactive, personalized, and prevention-focused approach could reduce these figures to $651 billion and $945 billion, respectively. Kidney disease shows a similar pattern: Spending is projected at $91 billion for medical and pharmacy ($222 billion with all associated expenses) but could drop to $65 billion and $187 billion, with greater emphasis on prevention.

These examples illustrate that prevention’s impact is not uniform—some conditions present greater opportunities for savings and improved outcomes. Figure 3 summarizes projected potential spending changes by disease and care category, including medical and pharmacy. It also includes health and wellness-related expenses paid by consumers and government-funded health-related activities. (See the full methodology for a comprehensive breakdown of assumptions by disease state).

Do prevention and early disease detection simply delay inevitable costs?

No. Prevention and early detection can do more than just postpone health care expenses; they can reduce total lifetime costs and improve quality of life. Chronic diseases such as diabetes and heart disease are significant drivers of health care spending, but preventing these conditions or managing them early can help avoid expensive treatments, hospitalizations, and complications.3 This approach tends to minimize the frequency and severity of high-cost medical events, especially in an aging population.

Deloitte actuaries found that proactive health measures can deliver a clear return on investment (ROI). By preventing disease or identifying and managing it early, individuals can experience significantly lower lifetime health care costs. Staying healthier longer can also reduce the duration and associated costs of serious illness at the end of life. For example, up to half of heart disease cases are linked to modifiable lifestyle factors such as diet, tobacco use, and physical activity.4 By adopting healthier behaviors—and investing in prevention, screening, and early detection—it is possible to delay the onset of heart disease and reduce its severity.

Longitudinal research conducted by the American Heart Association,5 and research published in The New England Journal of Medicine,6 indicate that adults with healthy hearts in midlife can delay the onset of heart disease by nearly seven years and compress the period of severe illness from almost five years to a little more than one.7 This phenomenon—known as compression of morbidity—means people can live longer, healthier lives while spending less time and money managing serious illness.8 Deloitte’s actuarial models estimate that more than $125 billion could be saved on heart disease alone by preventing or delaying onset, shortening the duration of severe illness and reducing hospitalizations.

Similar trends are seen with other conditions. For instance, up to 80% of strokes are considered preventable,9 yet 50% of stroke survivors experience long-term disability.10 Deloitte’s analysis found that advances in hypertension management, rapid surgical response, and digital interventions can not only decrease the incidence of stroke but also reduce the duration and severity of disability, resulting in substantial savings in hospital and rehabilitation costs.

For the individual, these interventions—in addition to lifestyle changes and regular primary care visits—can spark meaningful improvements in health and add multiple years of life span (the average expected number of years between birth and death) and health span (the average number of healthy years between birth and death). Previous Deloitte research concluded that proactive measures for managing health can add more than 20 years of health span.

This analysis shows that targeted investments in prevention and recovery can help bend the health care cost curve. Deloitte’s projections recognize that only a portion of the population will likely adopt healthier behaviors during their working years. While health care costs generally increase with age due to increased health needs and greater prevalence of chronic conditions, this is not inevitable for everyone. Some individuals might incur lower costs later in life if they maintain good health when they are younger. However, many factors can influence health as people age.11

The analysis suggests that—with the appropriate proactive investments—it may be possible to slow Medicare spending growth without raising taxes or reducing benefits. By making targeted investments in preventive care programs, enhancing care coordination and navigation, and promoting healthier lifestyles, Medicare could reduce health care costs over a beneficiary’s lifetime. As mentioned earlier, these strategies could help save Medicare more than $500 billion a year in medical and prescription drug costs, strengthen the program’s long-term financial future (see Medicare spending is on pace to more than double by 2031), and increase the number of years that beneficiaries enjoy in good health. The findings highlight the importance of considering innovation and strategic investment in health care delivery as policymakers address the long-term sustainability of the Medicare program.

Medicare spending is on pace to more than double by 2031

Medicare, established in 1965, provides health coverage to Americans age 65 and older and to certain individuals with disabilities. The program is funded primarily through a combination of payroll taxes (collected under the Federal Insurance Contributions Act), premiums paid by beneficiaries, and general federal revenues. However, as health care costs rise and the population ages, this funding structure is under increasing strain—especially since Medicare Parts B and D rely heavily on general revenues rather than dedicated payrolls.12 If these trends continue, the existing model may become unsustainable, placing greater financial pressure on both individuals and the federal budget.

Medicare is the largest single purchaser of health care in the United States13 and the second-largest federal program after Social Security.14 In 2023, the program spent about $848 billion and covered more than 67 million people.15 Enrollment in the program, in its current form, is projected to exceed 80 million beneficiaries by 2031, and annual spending could reach $1.8 trillion, driven by increased enrollment, greater demand for services, and rising health care costs. Medicare’s share of the federal budget is also expected to grow—from 3.9% of the GDP in 2025 to 5% by 2031.16

Approximately 10,000 people become eligible for Medicare every day—a trend driven by the aging baby-boomer generation.17 The last of this generation will reach Medicare eligibility in 2029. As more people become eligible for Medicare, the declining worker-to-beneficiary ratio will likely strain the program’s finances. Without intervention, this could force difficult choices.

Evidence-based practices can reduce US disease rates and health care spending

Treating and managing chronic diseases can be expensive. For example, the annual cost of managing diabetes in the United States is approximately $412.9 billion. Direct medical expenses, such as medications, doctor visits, and hospitalizations, account for about $306.6 billion, and indirect costs like lost productivity and absenteeism make up about $106.3 billion.18

Evidence-based practices can lower the risk of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, stroke, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes.19 Key preventive measures include regular physical activity, a healthy diet that is low in ultra-processed foods and added sugars, restorative sleep, stress management, limiting harmful substances, and strong social connections.20 In addition, early disease identification can enable more effective management when lifestyle changes alone are not enough. Because some chronic diseases develop silently over decades, prevention and early detection with appropriate diagnostic tools offer the best chance to reduce the impact of serious illness.21

Reducing health care spending will involve proactive investments and actions across several domains. In this analysis, each disease state was assessed across five categories that influence health: lifestyle, care quality and access, environment, genetics, and non-modifiable risks.22 For example, lifestyle factors include increased physical activity, better nutrition, and limited alcohol and tobacco use. Care quality and access involve improving access to specialists, rural health care providers, new treatments, and early screenings. Environmental factors include monitoring air and water quality and reducing exposure to harmful chemicals. Genetics cover enhanced testing for genetic predisposition, personalized interventions to minimize risk factors, and targeted treatments for genetic causes of disease. Finally, a non-modifiable factor such as age involves increased awareness and tailored approaches to support better health outcomes. Each disease and care state responds differently to these drivers, depending on underlying biological and physiological factors.

A multi-stakeholder initiative could unlock sustainable health care savings

Historically, efforts to control US health care costs have focused on treating or managing chronic conditions after they develop, rather than preventing them. While it is widely recognized that proactive, evidence-based investments in prevention and early detection can help reduce the risks and costs of chronic diseases, implementing these strategies involves upfront investment in new tools, technologies, and care models.23 Compounding this challenge, the current health care business model offers few direct financial incentives for health plans, employers, or health systems to prioritize long-term health improvements for their members, employees, or communities.

However, shifting from a reactive to a proactive approach is important for realizing the potential $2.2 trillion in annual savings and securing Medicare’s future. Such a transformation would involve coordinated action from multiple stakeholders, such as government, employers, health plans, and health systems, with each playing a unique and vital role.

Federal government

Government agencies can support this movement by incentivizing commercial health plans, especially employer sponsored plans, and Medicare to invest more in disease prevention. This can be achieved by promoting innovation through new payment models and expanding reimbursement for preventive care. As our analysis shows, longer life spans don’t necessarily translate to increased Medicare spending—particularly if people enter retirement in good health. Developing strategies that incentivize employers to support employees’ physical, mental, and social well-being could be key to lowering future health care expenditures.

Employers

Employers already contribute significantly to Medicare and health care spending.24 By redirecting some of these resources toward prevention, early disease detection, and other proactive measures, employers could improve the health of workers and their families, potentially reducing future health care costs and boosting productivity.

Health plans

Health plans have opportunities across most lines of business. In the commercial market, which includes employer-sponsored and individual insurance coverage, health plans could partner more closely with employers to encourage lifestyle changes among employees that help reduce premium costs. This could involve new product offerings, added benefits, and incentives that promote a healthier lifestyle. In government programs like Medicare Advantage, even small changes to access or digital solutions can help boost member engagement and health outcomes.

Health systems

Health systems have an opportunity to move beyond just treating diseases and focus even more on helping people, and the communities they serve, stay healthy. This is a goal that many, if not all, health systems strive to achieve. With government support and funding, along with encouragement from employers who want better health programs for their employees, health systems can invest more in these kinds of services.

Moving toward proactive care to help achieve sustainable Medicare savings

Ultimately, stakeholders could benefit from greater investments in disease prevention, early detection, and other proactive measures. Medicare could see reduced long-term spending, employers could benefit from a healthier and more productive workforce, and individuals could enjoy lower overall health care costs and improved quality of life (see Methodology: How Deloitte analyzed US health care spending and prevention scenarios).

However, realizing these benefits involves urgent, coordinated action. Stakeholders should consider working together to prioritize prevention, embrace innovative solutions, and align incentives to support proactive care. By seizing this opportunity for transformational change, a more sustainable health care system and a healthier future for all can be built.

Methodology: How Deloitte analyzed US health care spending and prevention scenarios

This analysis projects potential US health care spending through 2040 by categorizing and modeling medical and pharmacy claims data, with adjustments for prevention scenarios and population changes. The methodology below describes the actions and assumptions used to project both medical and pharmacy claims. A similar approach was used for health and wellness-related expenses paid by consumers and government funded health-related activities, although projections were not made at the individual claim level: Spending was assigned to disease and spending alignment categories, and projections were made comparable assumptions. For more information about how these spending categories were projected, please refer to the detailed methodology.

The analysis was broken into three core components:

- Claims categorization: Medical and pharmacy claims from 2019 to 2023 were classified into four categories and 21 disease states using data from the Komodo Healthcare Map™, the Global Wellness Institute, and CMS’s National Health Expenditure projections.

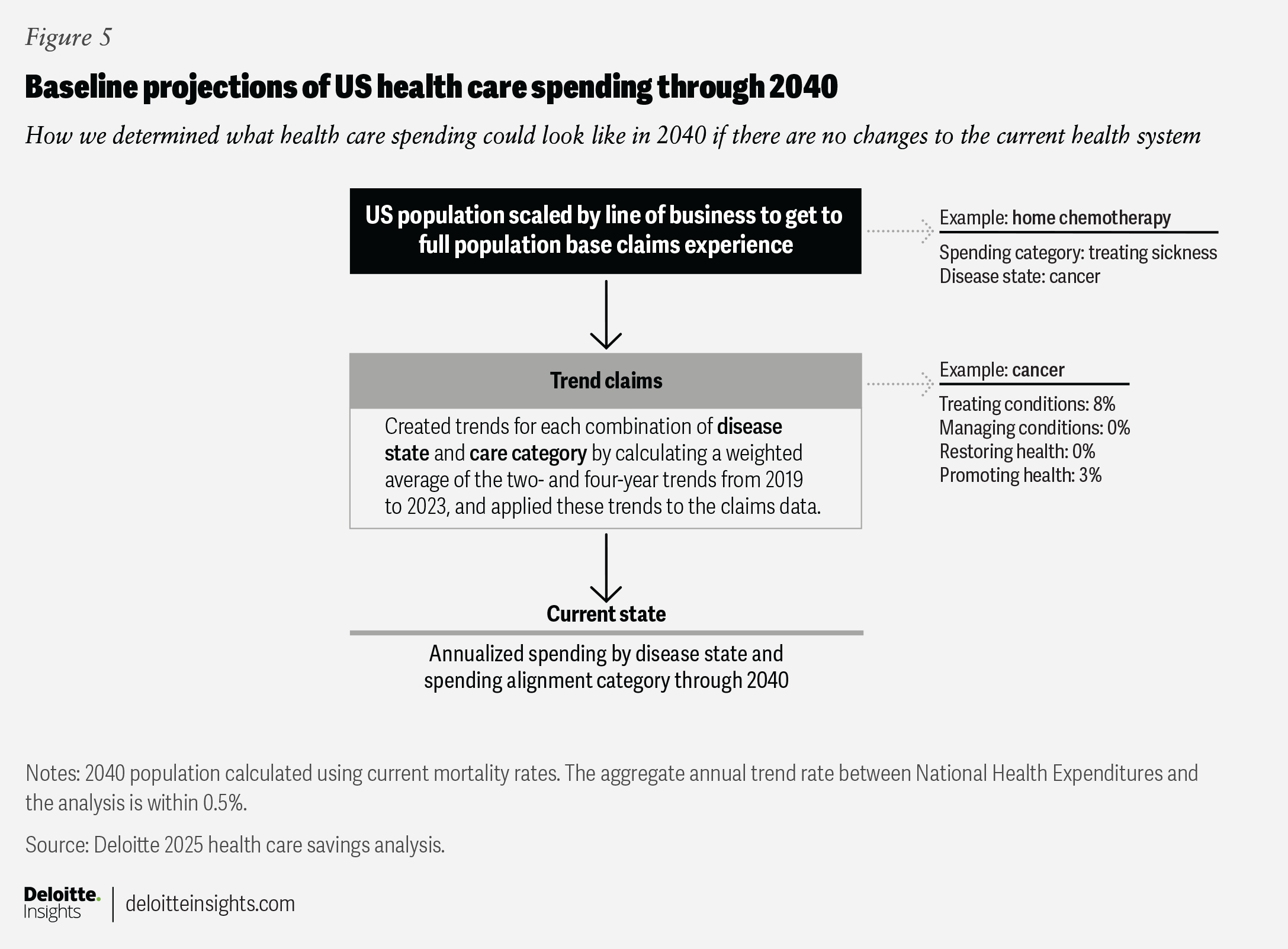

- Baseline projections: Historical claims were trended forward by disease state and category to estimate baseline spending through 2040. Trends were blended to minimize the impact of pandemic-related disruptions. Population growth and aging were factored in using standard mortality tables.

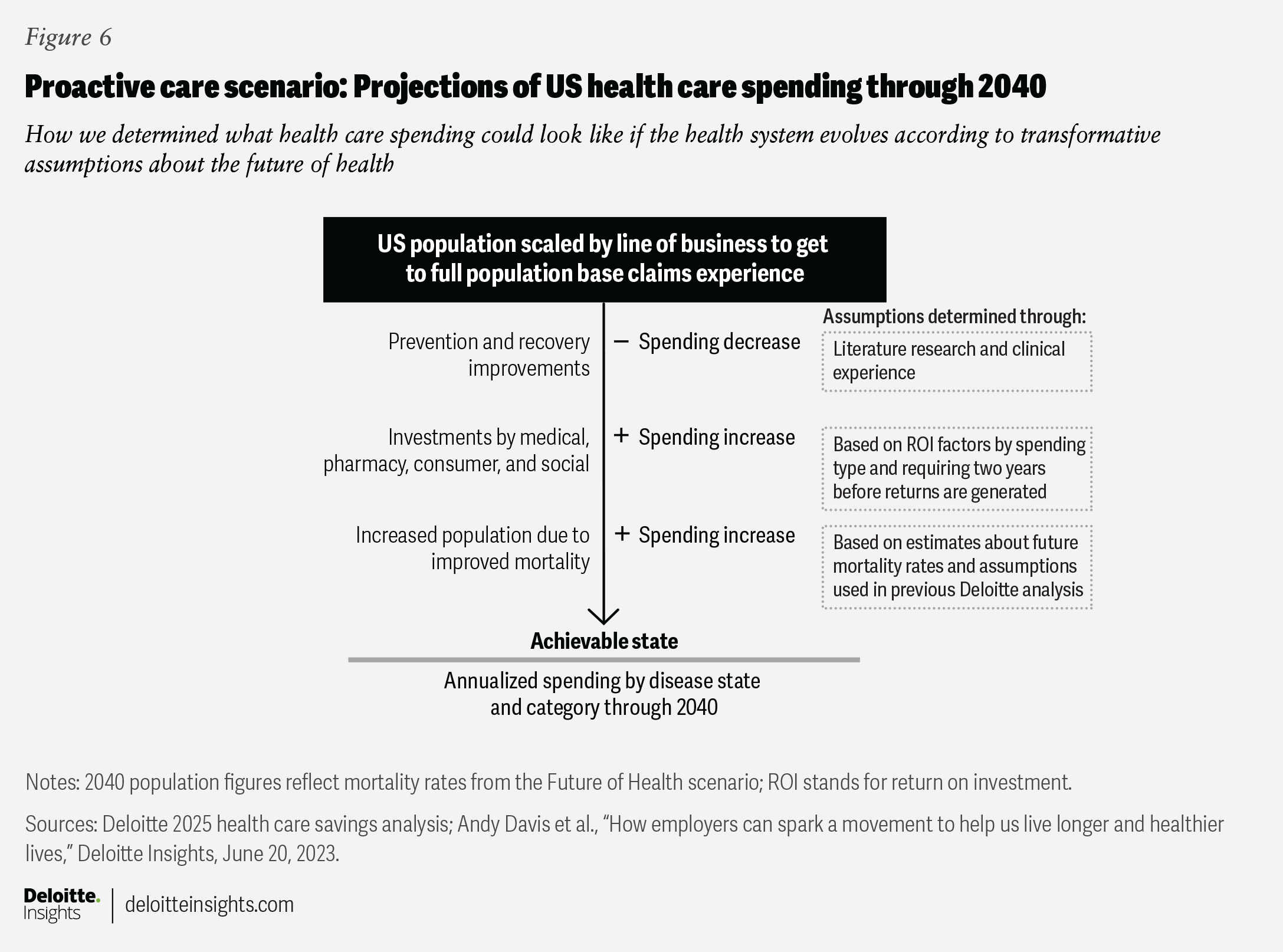

- Proactive care projections: Claims and other data were combined with assumptions of what might be achievable by reducing disease prevalence, minimizing complications related to disease management, and extending the number of healthy years lived.

To project potential future health care spending, medical claims were analyzed and mapped to 21 disease states. These results established a baseline for projected spending through 2040. Researchers then compared this baseline to a scenario with greater investment in disease prevention, using several key assumptions:

- Not all diseases are preventable, and not everyone will adopt healthier behaviors. The analysis uses published research, clinical experience, and knowledge of emerging technologies to estimate how much each disease state can be influenced by prevention.

- Prevention takes time to pay off. Investments in disease prevention typically require at least two years before generating a measurable ROI.

- ROI is modest but meaningful. The expected ROI for disease-prevention investments is relatively modest (about two times for medical and pharmacy), where slightly higher multiples used for other areas.

- Population aging is factored in. The model accounts for a significantly larger and older US population in 2040, reflecting demographic trends.

Categorization of historic spending

Data sources

Historic spending was analyzed across medical, pharmacy, and consumer spending categories. Medical and pharmacy claims data came from the Komodo Healthcare MapTM, covering 59 million people across commercial health insurance, Medicaid, Medicare Advantage, and traditional Medicare. Consumer spending data was sourced from the Global Wellness Institute and government spending was sourced from the National Health Expenditures.

Categorization process

Medical and pharmacy claims were grouped into service lines and care groups using Sg2 (medical) and MediSpan (pharmacy), and then further broken down by disease and therapeutic area. Actuaries classified spending into four categories (as previously defined) based on claim type and disease state for greater accuracy.

Population scaling

All values were adjusted to reflect the 2023 population and coverage types. For example, since Komodo data does not capture all Medicare enrollees, we calculated the ratio of Medicare coverage in the data and scaled it to match the likely total population (figure 4).

Projecting future claims to create a baseline

Medical and pharmacy claims data were organized by year, and annual trends were calculated for each disease state and category. Instead of using actual trends directly, we blended two- and four-year historic trends to inform the projections. This approach was used to minimize the impact of COVID-19 disruptions.

- Actual trends were used to create trend archetypes for each disease state and category, ranging from rapid growth (at 15%) to rapid decrease (at less than 10%). (See the detailed methodology for full tables of these archetypes.)

- Projections were not adjusted for future years or to match Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) National Health Expenditures (NHE) projections, though Deloitte’s assumptions closely align with the NHE projections for 2033. The study did not account for new drugs, loss of exclusivity, or new regulations.

- Population adjustments used standard mortality tables and assumed stable birth rates. These trended values established the annual baseline for projected health care needs (figure 5).

Claim projections

Actuaries projected likely claims by adjusting assumptions to reflect potential improvements, such as reduced disease prevalence, fewer complications, and longer life expectancy. Historic medical and pharmacy claims data was used to create trends by disease state and category. Key adjustments included:

Disease impact assessment

For 21 distinct disease categories, evidence and experience were used to determine how much each could be affected by lifestyle, health care quality and access, environment, genetics, and non-modifiable factors. Not all diseases were assumed preventable. Instead, each disease was assigned a high (70%), medium (45%), low (20%), or zero (0%) potential for improvement, based on available evidence and supporting narrative.

Cost reduction from improved care

Similar factors were used to estimate cost reductions from improvements in care, even when disease was detected. These assumptions were applied by disease state.

Investments were assumed to be necessary to achieve cost savings, with a two-year ROI period. Based on that assumption, money invested in 2024 would begin to generate savings in 2026. However, ROI varied by investment type:

- Medical and pharmacy assume a two-times ROI (every $1 invested in 2024 can generate $2 of savings in 2026).

- Social and consumer investments have different multipliers of four times and three times, respectively. Investments do not create perpetual savings. Instead, ongoing annual investment is needed to sustain savings.

Population adjustments

As with the baseline projections, mortality changes were factored in using updated mortality tables from a 2023 Deloitte actuarial study. The assumptions from that study are consistent with the latest research used in this analysis. The model assumes more people will be covered in the United States in 2040, leading to higher aggregate spending compared to the baseline.

These adjustments provide an annualized alternative spending scenario, which is compared to the baseline to the baseline to assess the impact of potential improvements (figure 6).

Medicare population

The Medicare population was modeled separately. For this group, no changes were made to trend rates or to prevention and maintenance assumptions; the only adjustment involved the population factor. Because the Medicare group tends to be particularly sensitive to changes in mortality, a new factor was created using updated mortality data. The model assumes that individuals who become eligible for Medicare will enroll in coverage. Each year’s baseline population is calculated by adding new enrollees and subtracting those expected to die, based on current mortality rates. The updated projections based on a shift to proactive care use a factor that assumes more people will reach Medicare age and live longer, requiring more years of coverage.