How investment management firms can benefit from the regulatory environment in 2025

Regulatory changes could offer fresh prospects for profitable growth in the next year

Ryan Moore

Paul Kraft

Meghan Burns

Sean Collins

The truism, “change is the only constant,” may adequately sum up the US investment management regulatory environment when any new administration takes the helm. In the first six months of the 2017 administration, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) proposed four new rules and flagged 33 more on its regulatory agenda.1 In 2021, it proposed two but signaled a much heavier agenda with 49 potential rules to come.2 While in the first six months of 2025, the SEC did not propose any new rules, the commissioners did manage to announce 25 rule updates and one concept release.3 At first glance, one might expect this to signal a significant amount of rulemaking action, but a closer look reveals that these actions by the SEC mostly either pushed out dates for compliance or withdrew previously proposed and finalized rules entirely.4 What appears to be the SEC’s lighter stance on setting new rules could be representative of a change in mindset as it considers how it might adjust its focus, approach, and capacity for regulations across industry issues. Over the next year, investment management leaders of regulation-ready organizations will likely concentrate on the strategic growth opportunities that may present themselves, given the seemingly shifting regulatory attitudes toward digital assets, retail access to private markets, dual share classes of mutual funds, and exchange-traded funds (ETFs).

Understanding the current scenario in light of our 2024 forecast

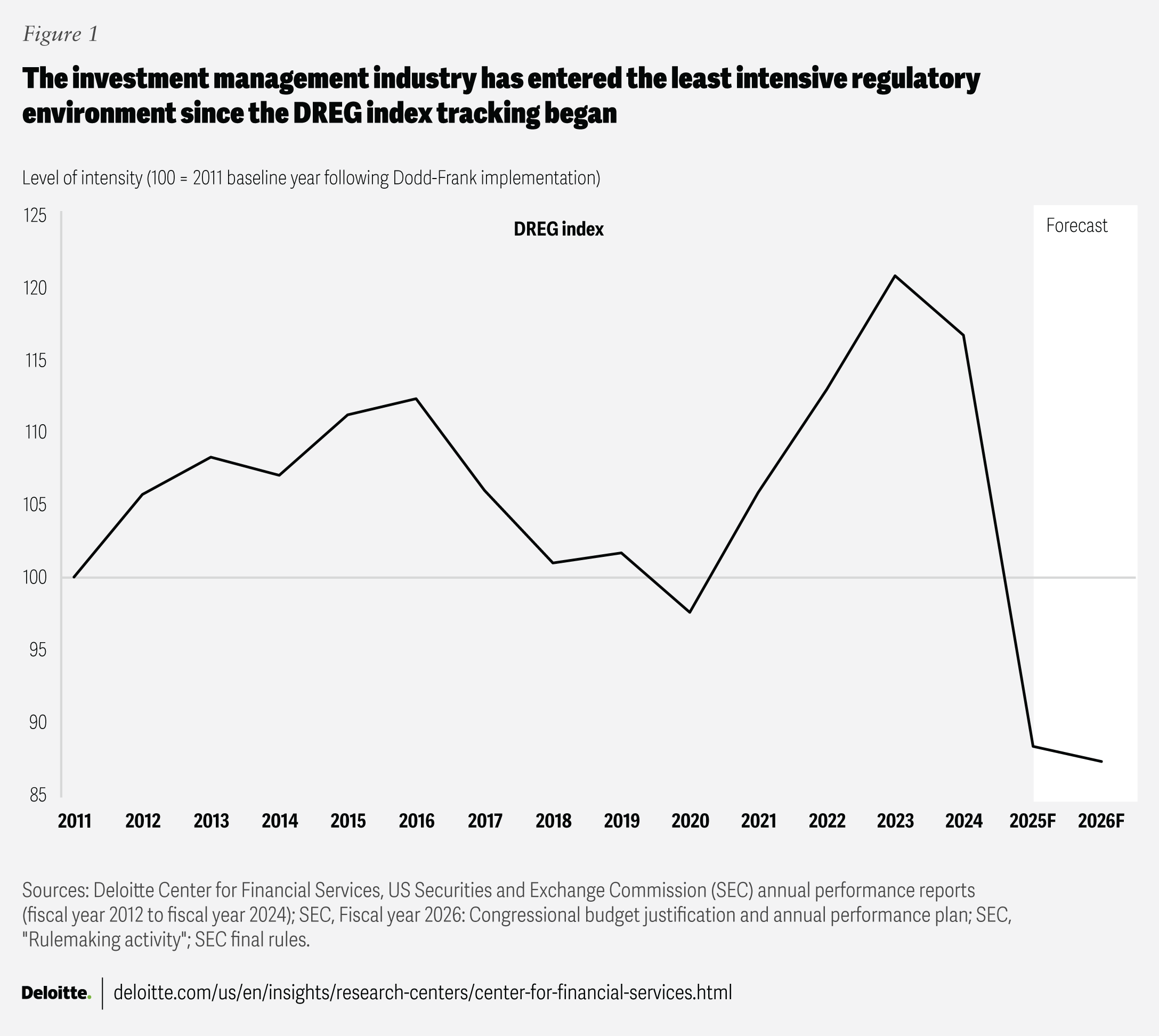

After years of keeping up with frequent and fast-moving regulatory shifts, many investment management leaders may now have an opportunity to reassess their companies’ regulation readiness in relation to compliance capabilities and risk management frameworks. The three stages of regulation readiness are sensing and influencing, planning and prioritizing, and implementation.5 Effective coordination when implementing changes based on regulatory shifts may warrant increased attention as investment managers explore new products and markets. The Deloitte Center for Financial Services regulatory index (DREG) provides investment management leaders with insights to help them more effectively plan and prioritize emerging regulatory trends affecting their industry. As described in our 2024 report, many leaders appeared to remain steadfast in the face of an active US regulatory environment. The index’s previously forecasted value of 125 reflected this higher expected level of intensity for 2024 for what would have been the most intense regulatory environment in the 13 years tracked by the index. The primary drivers were:

- Actions taken by the SEC through more final regulations adding requirements

- Increasing amounts of fines and penalties for non-compliance

- Higher enforcement budget allocations

The actual 2024 DREG value came in at 117 (figure 1), representing a decrease from the previous year and indicated a less intensive regulatory environment than initially forecasted.

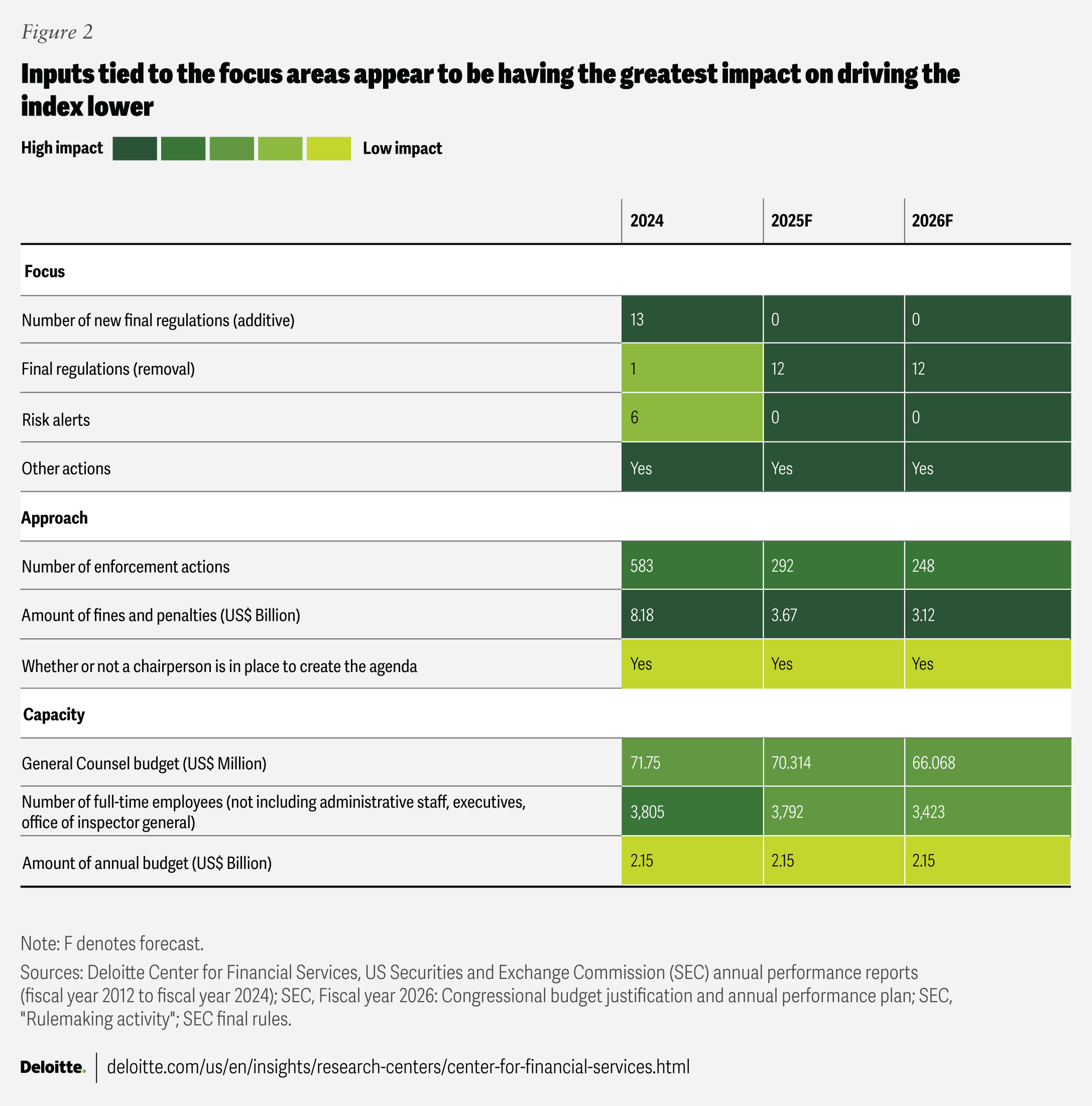

The main drivers behind the drop in the 2024 DREG index level can be attributed to two of the inputs that relate to the regulator’s focus (figure 2). First, we forecasted that 21 regulations would have added requirements, but only 13 actually did.6 Second, the “other agency actions” input variable had a downward impact due to the federal court’s decision to vacate two final rules, as well as one whose effectiveness was stayed over the course of 2024.7 These rules would have imposed substantial new compliance requirements on traditionally less-regulated industry segments such as private funds and hedge fund managers. For regulation-ready organizations, the coming months may represent an interesting period for innovation. The SEC seems poised to remove certain regulatory restrictions on these products, which could signal an openness to expanding access to retail investors, presenting potential for product development and a growth opportunity for investment managers.8

The 2025 estimated index value reflects rapid shifts in the federal regulatory environment that have taken place since the new administration assumed office in January. The 2025 value marks the lowest level on record. This marked decline can be partly explained by the index’s baseline year of 2011, which was effectively the beginning of nearly a decade-long effort to implement the Dodd-Frank Act.9 We attribute index levels above 100 from 2012 to 2019 to this Congressional mandate, after which the index briefly dropped below 100 during the Presidential election year of 2020, as the SEC almost doubled the number of rules classified as deregulatory from the prior year.10

A closer look at what’s changed in 2025

With the former regulatory policy agenda largely reversed, comparatively few proposed regulations are being finalized in 2025, which is one driver of the index’s lower level.11 In fact, the SEC formally withdrew 17 outstanding rule proposals in June, ensuring that they will not move to the final rule stage, at least in their current form.12 Other drivers identified by the index include a deceleration in enforcement, the aforementioned extended compliance timelines, and the Supreme Court decisions whose effects will likely be felt for years to come.

Regulatory guidance (for example, no-action letters, staff statements, risk alerts) can be a policy tool that helps restrict business activities or loosen regulatory restrictions. In recent months, regulators using guidance to permit activities—rather than using guidance to limit them—appears to be a pivot that is likely helping decelerate the regulatory environment.

For example, the SEC has used no-action letters to allow firms to offer products to retail investors that were previously restricted only to accredited investors.13 Staff guidance has also been used to exclude broad categories of digital assets from the securities laws, reduce regulatory impediments to tokenizing securities, and formalize a policy on which closed-end funds may be marketed to retail investors.14 Guidance can be an efficient and effective policy tool. However, it can also be tenuous due in part to how easily it can be withdrawn and is generally most effective as an interim measure. Thus, guidance can also be a precursor to eventual rulemaking. Whether increasing or reducing regulatory requirements, rulemaking in accordance with the Administrative Procedure Act appears to remain a more durable avenue for instilling policy change, especially in a fluctuating political environment like the United States has experienced over the last decade.

This trend, quantified by the DREG, helps speak to a federal regulatory environment for investment management that is implementing new requirements and costs on the industry at its slowest rate in nearly 15 years.15 This will likely create opportunities for firms that know where to look for them.

What can leaders do to benefit from this less intensive regulatory environment?

Today, many regulation-ready investment managers may be able to adjust from a reactionary posture to a more proactive one focused on emerging opportunities. Direct statements by some of the regulators themselves could suggest an environment more amenable to industry priorities, and a firm’s best approach may be to engage regulators, particularly in areas where their desired business strategy runs up against existing regulatory requirements. Recent comments from the SEC may provide some regulatory guidance as some firms look to identify new areas for profitable growth. The SEC indicated a shift from the agency’s previous position that closed-end funds will only be declared effective so long as they do not invest more than 15% of assets in private funds, unless it is only offered to accredited investors.16 By removing this restriction, the agency hopes to provide retail investors with “new investment opportunities to the extent they align with their risk tolerance and investment objectives.”17 Given this refreshed approach by the SEC, both alternative and traditional investment management firms may want to explore expanding the client segments offered private capital investments or launching new ’40 Act products, such as closed-end funds that include increased private fund allocations.18

Other agency actions can also help clarify the path for increasing retail investors’ access to private funds. In August, the US Department of Labor rescinded its previous position that 401(k) plan fiduciaries were “not likely suited to evaluate the use of PE investments” in retirement plan accounts.19 As a result, plan fiduciaries can consider a broader set of investment choices, including private equity, for their plans’ participants without fearing they will be accused of abandoning their fiduciary responsibilities by offering more investment choices.

The coming months will likely bring clarification concerning dual share classes of ETFs and mutual funds.20 This can help provide firms with an opportunity to offer an ETF share class of an existing mutual fund, and vice versa, without having to create a completely new fund. In any case, keeping investor protection—especially regarding fiduciary obligations—and establishing written policies that incorporate adequate training to prevent violations of the marketing rule, at the forefront of client segment or new product strategies, remains of the utmost importance.21

Investment management firms should not allow their compliance posture to atrophy. Rather, they should refocus efforts to support growth strategies and address emerging risks. Also, given the emergence of new technologies with artificial intelligence leading the way, the regulatory break in the action can help allow regulation-ready organizations to assess and enhance their compliance and risk management platforms and enterprisewide AI programs. This can help create more efficiency and resiliency in the future when the regulatory environment may shift once again. While the downward shift in the DREG index suggests a much lower level of regulatory intensity for the near future, perennial regulatory focus areas like fee transparency, fiduciary standards, cybersecurity, and marketing will likely continue to be important to help maintain a robust regulatory-ready posture. In fact, each of these may come into play as private market investments are increasingly marketed to retail investors. A more permissive SEC does not equate to a regulation-free environment, and investment managers with positive regulatory relationships and innovative leadership should be well positioned to better capitalize on new market opportunities.