Managing workforce risk in an era of unpredictability and disruption

Talent can be an organization’s greatest strength and one of its most challenging assets. What are some leading organizations doing differently to help mitigate workforce risks?

Joseph B. Fuller

Reem Janho

Michael Griffiths

Michael Stephan

Carey Oven

George Fackler

How aware are organizations about workforce risks?

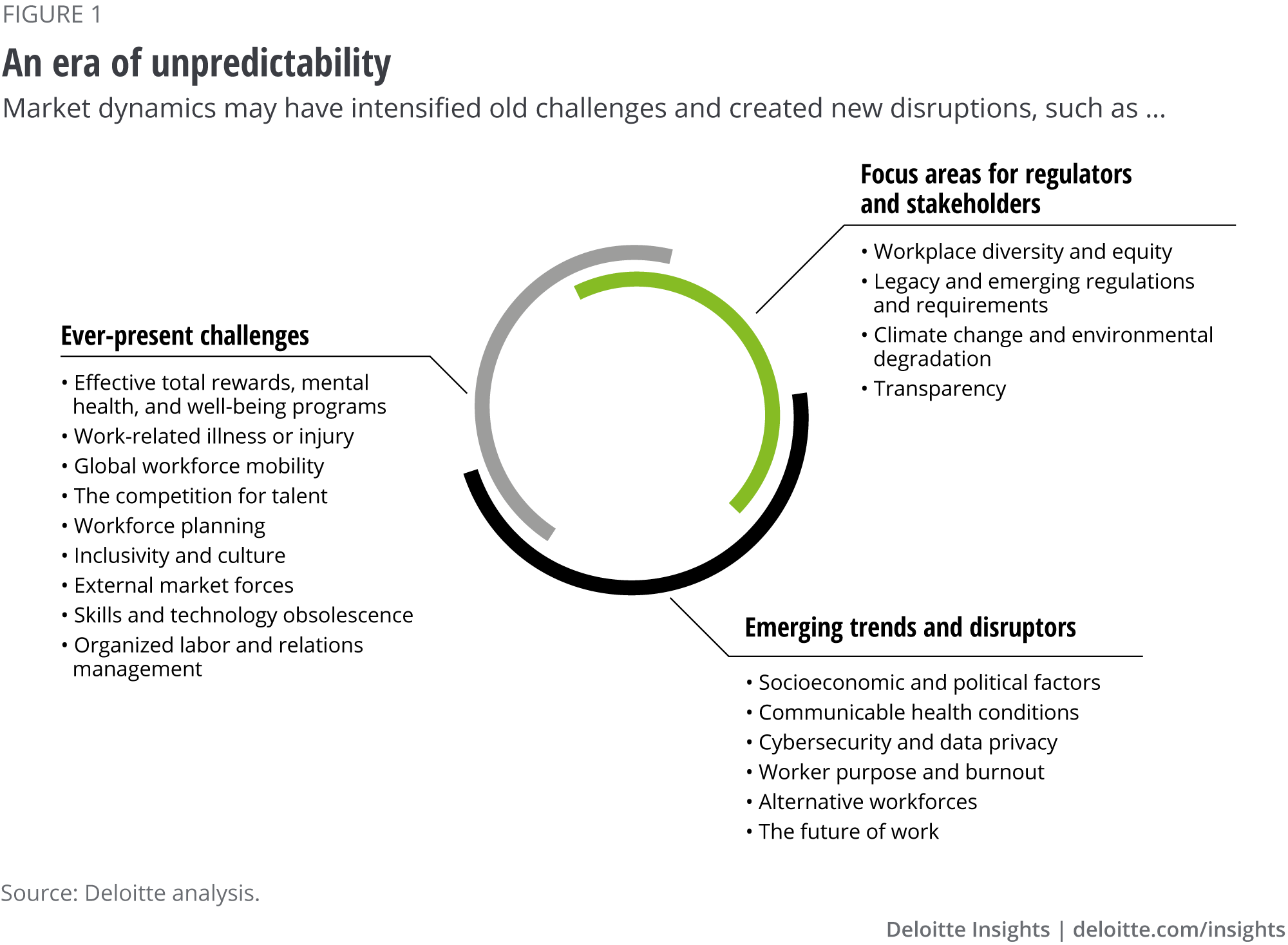

Over the past few years, organizations have faced an increasing number of risks with the potential to disrupt their financial and operational performance, reputation and brand, and compliance with regulations. Such risks include actions by aggressive competitors, emerging disruptors, and mounting pressures created by diverse constituencies ranging from lawmakers to activists. A notable trend across these new challenges and emerging market focus areas is the growing impact they often have on the workforce (figure 1).

Historically, organizations’ main workforce-related concerns often rested almost entirely on productivity and cost competitiveness. Today, workers can affect their employers in a variety of ways—from their behavior on social media and adherence to data security policies to their alignment with the company's purpose and their willingness to upskill.

Many of those factors might affect an organization’s ability to attract, develop, and retain a workforce with the appropriate skills. Moreover, as skilled workers have ever-more alternative employment options and workforce participation rates continue to trail behind pre–COVID-19 numbers,1 the market for talent appears poised to remain tight for the indefinite future. With talent likely to become one of the most important factors determining organizational success, leaders will need to do everything they can to compete for critical talent. For instance, 79% of business executives that participated in Deloitte’s recent Skills-Based Organization study agreed that the purpose of their organization should be to create value for workers as human beings (as well as for shareholders and society at large).2 Similarly, worker well-being was among the top-ranked trends in Deloitte’s 2020 Human Capital Trends study, where 80% of respondents identified it as critical to their organization’s success.3

Table of contents

- How aware are organizations about workforce risks?

- The disconnect between the importance of workforce risk and limited oversight from C-suites and boards

- Pioneers are leading the charge in effectively managing workforce risk

- Understanding workforce risk

- Manage and govern workforce risk

- Toward the next frontier of workforce risk management

- Deloitte services

“Workforce risk is more strategic than other [risk] elements. You can’t say people are your biggest asset if you’re not managing the risk that surrounds your people. How you manage workforce risk will affect your share price and shareholder value.”

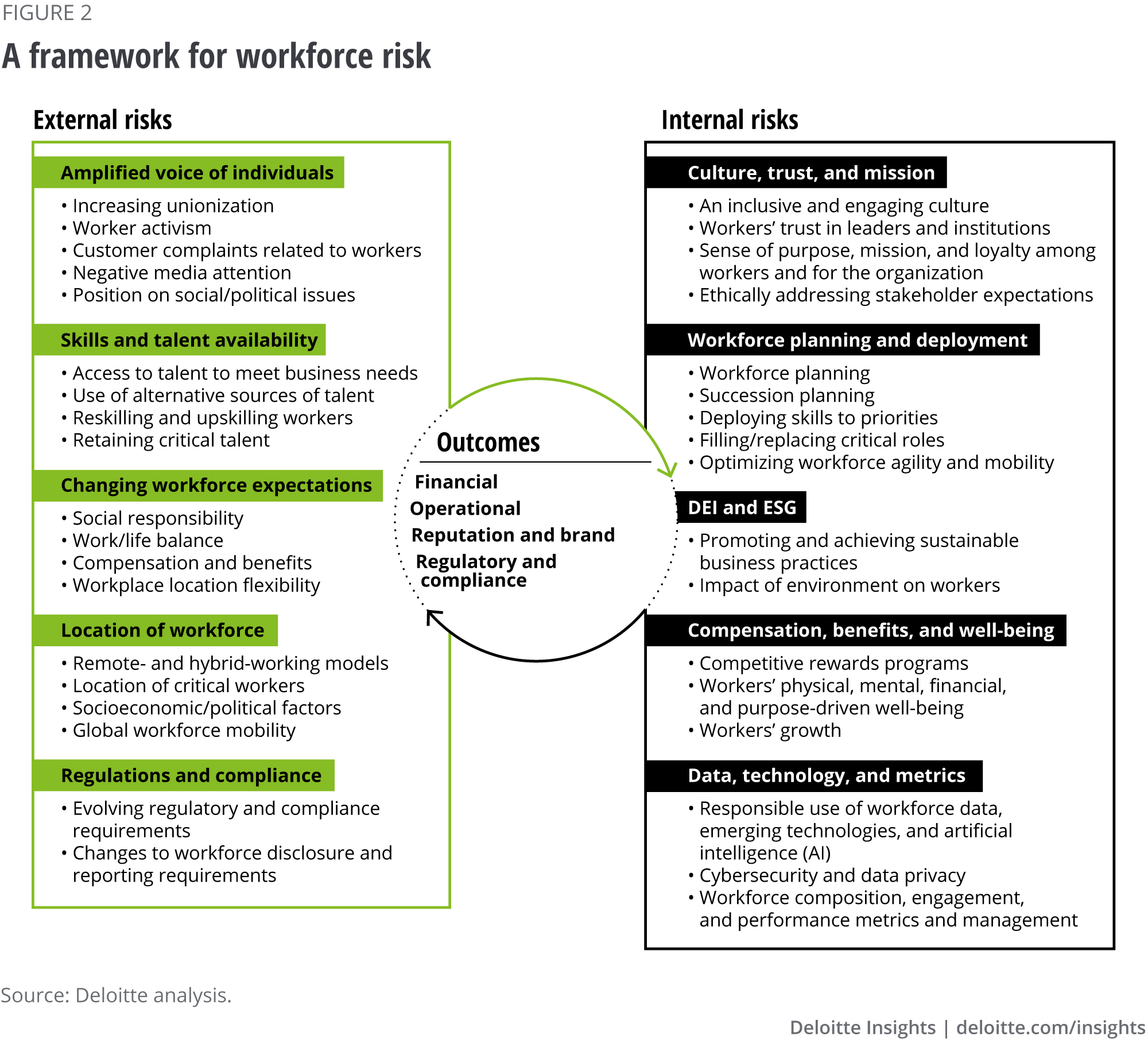

While leaders are undoubtedly aware of the challenges that talent shortages and attrition could pose to their organizations, there are many broader, often-overlooked dimensions of workforce risk that are also important to consider. A more comprehensive view of workforce risk includes any workforce-related danger to an organization’s financial, operational, reputation and brand, and regulatory and compliance outcomes (figure 2). To help effectively manage workforce risk, organizations should first have a deep understanding of the various external and internal sources of workforce risk, as well as their potential exposure to these today and in the future.

Organizational leaders also face mounting pressure to address workforce-related challenges head on. Recent and expected changes to human capital disclosure requirements by both the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)4 and International Organization for Standardization5 call for C-suites and boards to be even more transparent in reporting their organizations’ management of and investment in their workforce.

To explore how C-suites and boards are viewing and addressing workforce risk, we conducted both quantitative and qualitative research—surveying 875 different C-suite leaders, executives, and independent board members, as well as interviewing nearly a dozen others. (See the sidebar “About the research” for more details.)

Our analysis of responses from survey participants indicates:

- Most organizations have neither a clear, holistic definition of workforce risk nor widespread knowledge and expertise about the topic.

- The majority of respondents focus on reacting to the workforce risks that threaten short-term business objectives at the expense of strategically planning for tomorrow’s challenges.

- Nearly all organizations can substantially improve how they measure and monitor workforce-related risks.

- Boards and C-suites provide limited oversight over workforce risk and rarely have explicit governance models in place to assess the impacts of workforce risk on their organization.

However, about one in 10 of the leaders we surveyed come from organizations that view workforce risk factors more holistically and spread responsibility for effectively measuring and managing these risks throughout the organization. We call them Pioneers. Our analysis revealed that not only are Pioneers better prepared to effectively manage workforce risk, they also self-report better business performance than their peers across a wide range of key performance indicators (KPIs).

About the research

Our research findings are based on a survey, qualitative interviews, and market research. In the summer of 2022, Deloitte collaborated with Oxford Economics and surveyed 875 organizational leaders representing a mix of national and international companies with operations in the United States—including 734 C-suite leaders, 75 independent board members, and 66 executive leaders—to understand how they view workforce risk and the actions their organizations are taking to identify, monitor, and address various underlying elements of workforce risk. We also interviewed nearly a dozen C-suite leaders and board members.

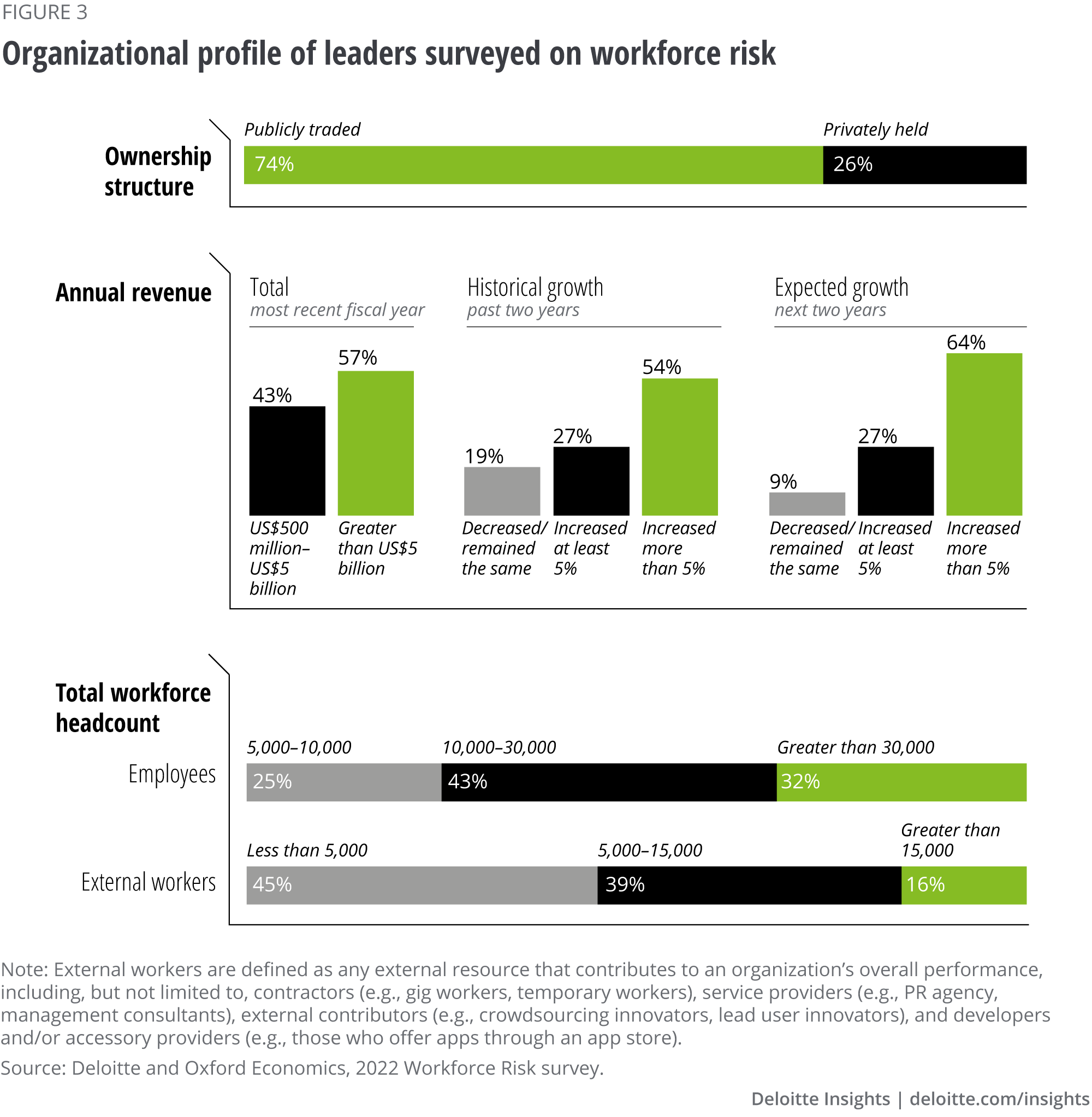

Survey participants represented organizations from 16 unique industries with the characteristics outlined in figure 3 (based on self-reported figures).

The disconnect between the importance of workforce risk and limited oversight from C-suites and boards

In recent years, market trends and external pressures have elevated the collective focus on the topic of workforce risk. For instance, 81% of executives that responded to Deloitte’s 2023 Human Capital Trends survey indicated that both anticipating and considering external risk factors (i.e., societal and environmental) to inform workforce-related decisions is critical to an organization’s success.6

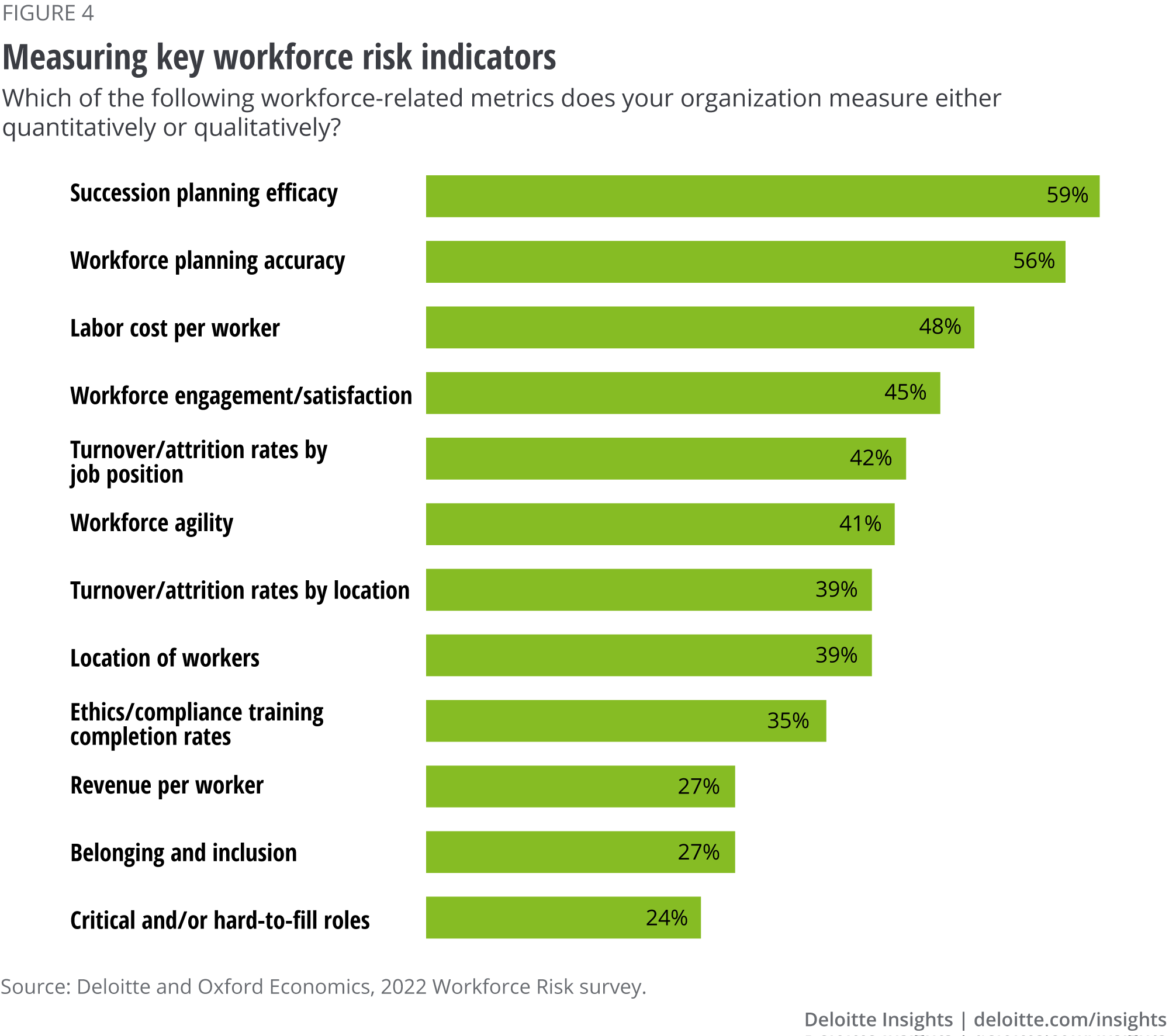

However, most organizations tend to focus only on standard, rote workforce metrics. Analysis of thousands of SEC registrants’ human capital disclosures revealed that most report only widely available workforce data such as demographics, acquisition and turnover rates, succession planning, and total rewards offerings.7

Our survey respondents indicated that succession planning, workforce planning, and labor costs top the list of metrics their organizations most frequently capture. However, many of the issues that responding C-suite leaders often tout as a high priority, such as belonging and inclusion or filling critical roles, are measured far less frequently (figure 4).

Likewise, many boards do not appear particularly engaged on these issues. Only 42% of respondents indicated that they include workforce risk in board agendas and oversight, while little more than half include workforce risk on the agendas of existing board committees.

Most organizations that participated in the survey may not be adequately addressing workforce risk

Of the C-suite, executive leaders, and board members we surveyed:

- 34% believe their organization is very or extremely prepared to effectively manage workforce risk over the next three years.

- 40% say their boards are very knowledgeable about workforce risk.

- 42% say they include workforce risk in board agendas and oversight.

- 44% strongly believe the workforce-risk-related metrics their organizations capture give an adequate view of their exposure to workforce risk.

- 52% include workforce risk on the agenda of existing board committees.

What could be behind this disconnect? As C-suites and boards grapple with a host of external risks—particularly related to reputational, environmental, social, technological, political, and economic issues—many tend to focus on the immediate operational and financial effects, while risks with longer-term implications could receive lower priority. Focusing on short-term “period next” items is no doubt important, but doing so at the expense of addressing the root causes of workforce risks may cause companies to react only to risks that have become so apparent as to be undeniable.

Additionally, many leaders may continue to rely on legacy processes to manage workforce risk factors over time, such as planning their headcount and safeguarding access to critical emerging skills. Rather than taking time to identify underlying factors or tackle complex strategic challenges, discussions about the workforce may often result in simple “checking the box” exercises that include tracking common workforce metrics such as diversity quotas, compliance adherence, and variances in labor costs, versus budget. Unfortunately, those processes can often fail to adequately capture the emerging realities of a dynamic, evolving market landscape. Such a short-sighted view may be due, in part, to a lack of maturity in workforce risk management capabilities in many organizations. Instead of evolving, they may continue to only focus on the existing financial, operational, and compliance risks that they have historically assessed.

Our survey findings suggest an additional factor may be driving this disconnect: a sense of overconfidence that can lead to both complacency and limited oversight of workforce risk (see the sidebar “The confidence conundrum”).

The confidence conundrum

Many organizations whose leaders responded to our survey appear to possess a false sense of confidence about how effectively they manage workforce risk, resulting in limited oversight by the C-suite and board. More than half (53%) of our respondents said they are fairly or extremely confident in their organization’s ability to effectively manage various types of workforce risk, yet only 34% believe their organization is sufficiently prepared to effectively manage workforce risk over the next three years. We call this paradigm of conflicting perspectives the confidence conundrum.

While many respondents believe their organizations are effectively managing workforce risk, most of those same organizations seem to lack the widespread knowledge, comprehensive measurement approaches, and robust management practices that may be necessary to succeed. Not only do some leaders seem to possess a limited understanding of workforce risk, but those same deficits, coupled with overconfidence, could prevent them from recognizing where they fall short and the resulting workforce risks they might incur.

Whether due to anchoring bias (focusing only on historic risks) or recency bias (fixating only on imminent risks), leaders shouldn’t overlook the broader constellation of workforce risks that could impact their organizations.

Though it appears to be perceived by many as a “known known,” our survey results indicate workforce risk could be more commonly an “unknown unknown” for many in leadership.

So how are leading organizations managing and mitigating workforce risks effectively? Our survey data may offer a clue.

Pioneers are leading the charge in effectively managing workforce risk

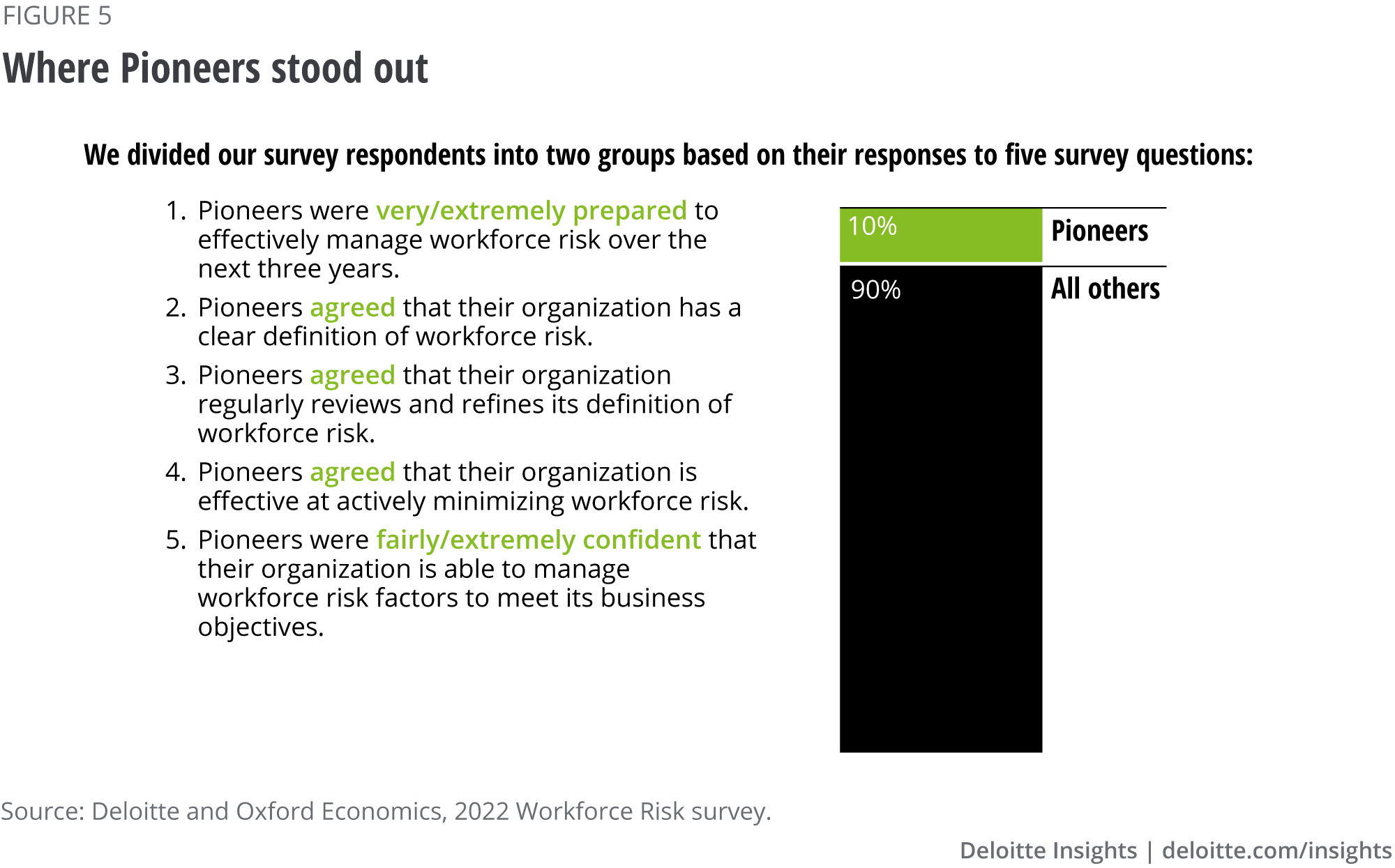

To better understand which organizations possess the most effective workforce risk management capabilities, we calculated a management efficacy score based on survey responses to a select set of questions. The questions used indicate how effectively respondents believed their organizations: (1) minimize their workforce risk today while adequately preparing for tomorrow; (2) clearly articulate and constantly refine their definition of workforce risk; and (3) manage various workforce risks to meet their business objectives. We aggregated those three measures into a single score that was used to help differentiate leading organizations.

We characterized those in the top 10% of scores as Pioneers: a group of organizational leaders not only confident, but seemingly justifiably confident, in their ability to manage workforce risk. This confidence appears backed by a holistic understanding of workforce risk and their utilization of more sophisticated mitigation practices to manage it.

The remaining 90% of respondents fall outside of the Pioneer category. Though some excel in one area or another, they do not exhibit the same holistic, ostensibly effective approaches as Pioneers in their management of workforce risk. (See figure 5 for the questions used and breakdown of respondents across each category.)

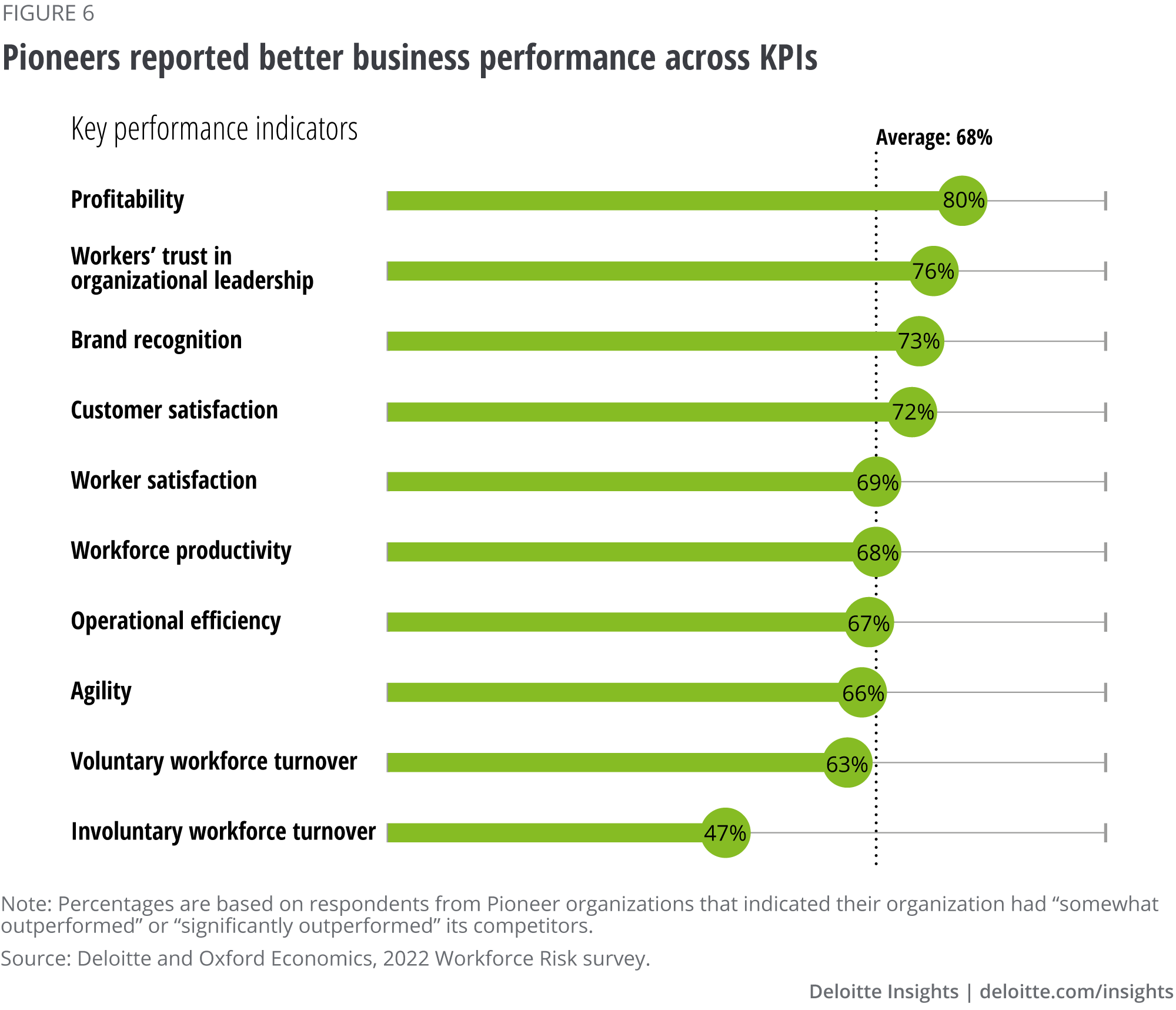

Furthermore, nearly seven out of 10 Pioneers reported outperforming the market on average across every measured KPI such as worker trust in leadership, customer satisfaction, and operational efficiency. For instance, roughly 70% of Pioneers indicated they had outperformed their competitors in areas tied to core business outcomes, including profitability, operational efficiency, and brand recognition (figure 6).

What can other organizations learn from Pioneers about addressing workforce risk? The following sections of this article explore actions organizations can take, as well as how Pioneers:

- Understand workforce risk by developing a clear and expansive definition that accounts for the full array of potential and underlying internal and external sources of workforce risk.

- Measure and monitor workforce risk by using real-time data and metrics, applying specialized methods and tools to help identify future potential dangers, and more transparently reporting and disclosing workforce-related information.

- Manage and govern workforce risk by proactively developing mitigation strategies and assigning clear oversight and ownership both vertically (from line managers to the board) and horizontally (across functions outside of HR).

Understand workforce risk

The transformation journey …

From: A traditional definition of workforce risk with siloed knowledge and expertise

To: A clear and expansive definition of workforce risk and shared knowledge and expertise across the enterprise

Possessing a clear and expansive definition

While Pioneers have made progress in comprehending the extent and complexity of workforce risk, our research shows most organizations still struggle to do so in a clear, concise, and comprehensive manner.

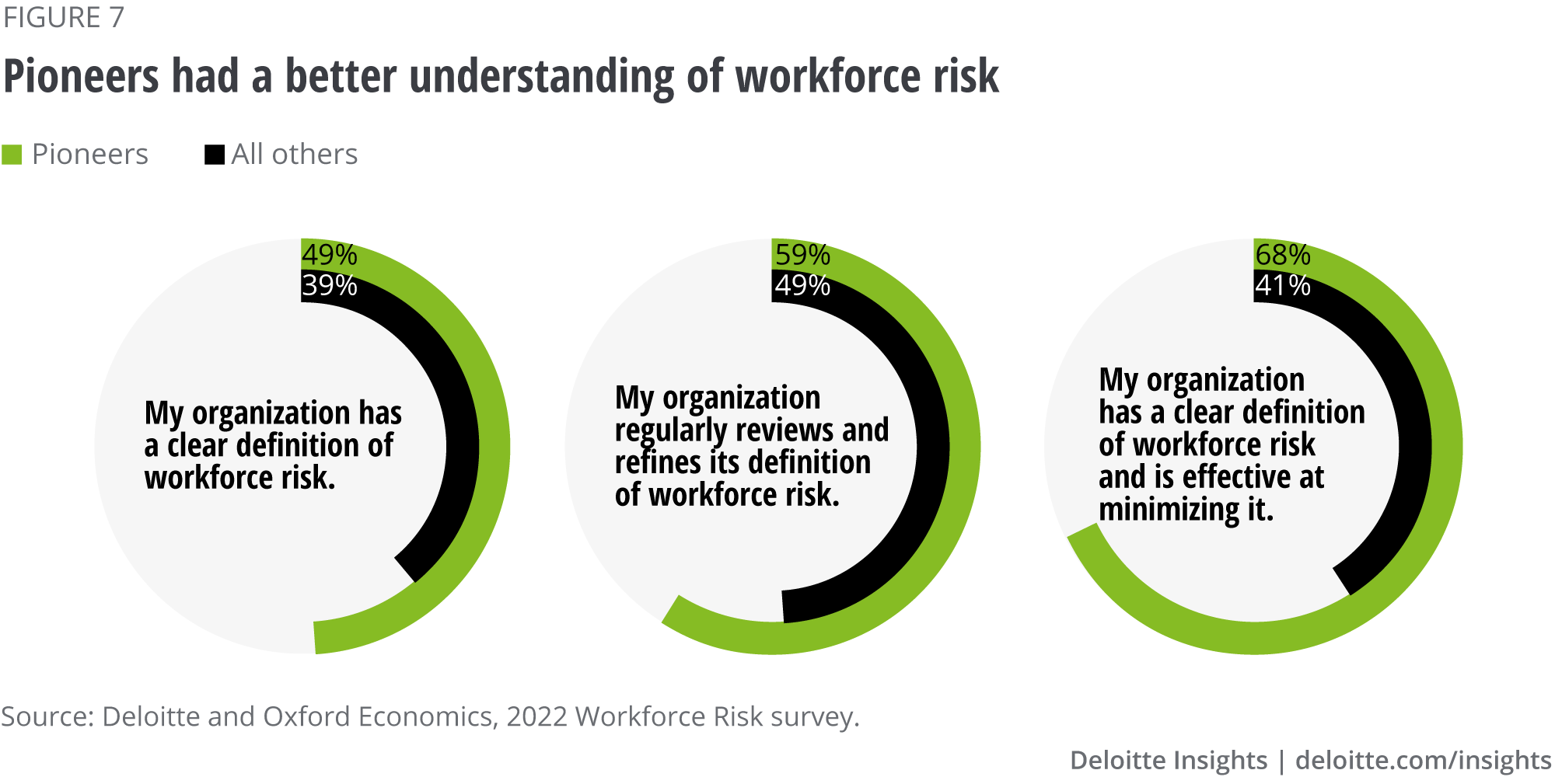

Pioneers were 26% more likely than other respondents to report that their organization had a clear definition of workforce risk. Notably, Pioneers and non-Pioneers were more likely to report regularly reviewing their definition of workforce risk than reporting having a clear definition (figure 7). This means that despite continual refinements to their definition of workforce risk, many organizations appear unsatisfied with it.

Spreading knowledge and expertise across the enterprise

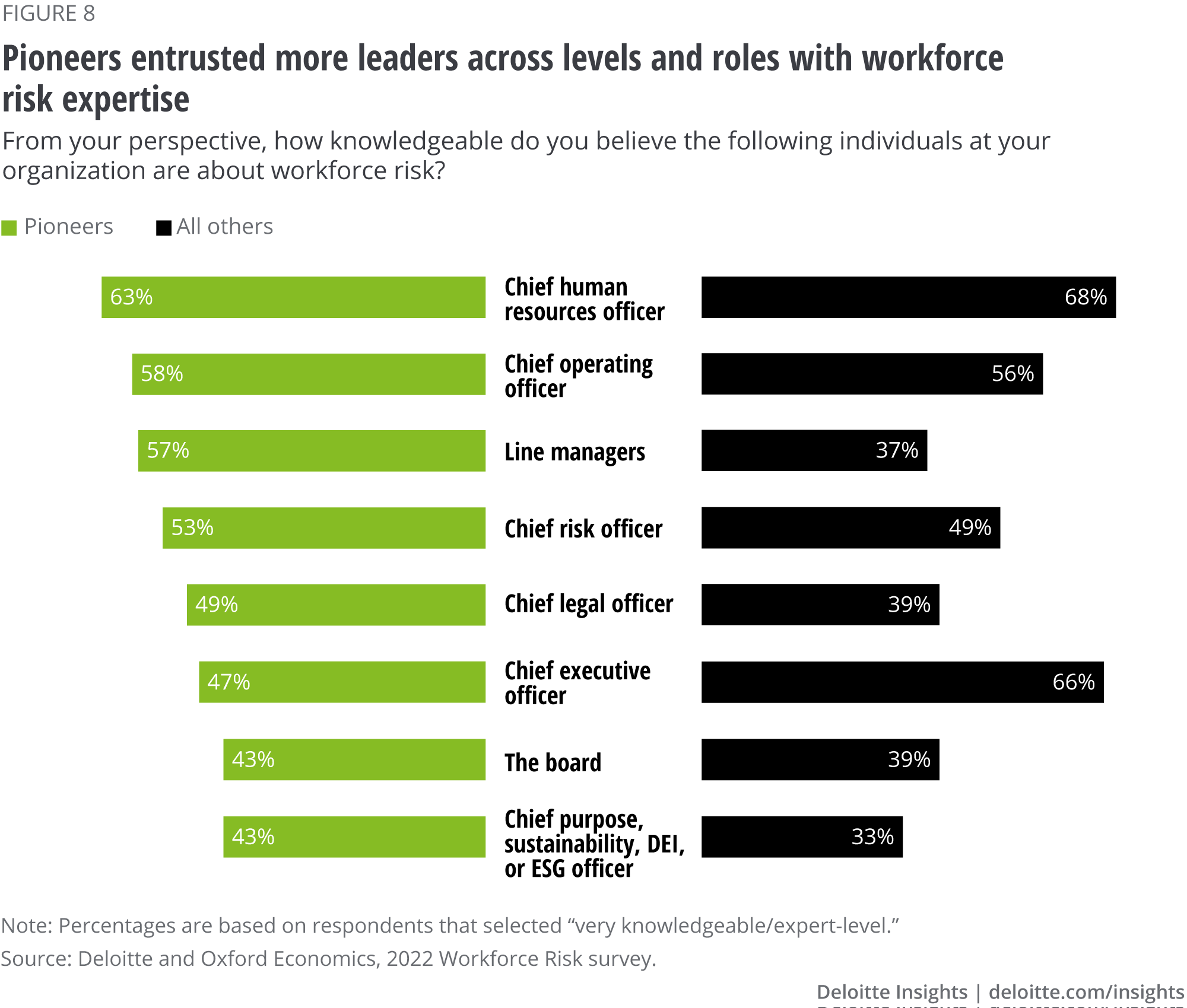

Pioneers seem to recognize that workforce risk management is not purely a C-suite issue. We asked respondents to indicate how knowledgeable they believed various C-suite, board members, and line managers (sales managers, supply chain managers, office managers) were about the topic. Both Pioneers and their peers graded chief human resource officers (CHROs) and chief operating officers among the three roles most knowledgeable about workforce risk. However, Pioneers were over 50% more likely than all others to identify line managers as having expert-level knowledge of workforce risk (figure 8). These findings suggest that Pioneers not only anticipate their line managers will be involved in managing workforce risks, but they also feel they could trust them to do so competently.

Understanding underlying sources of workforce risk

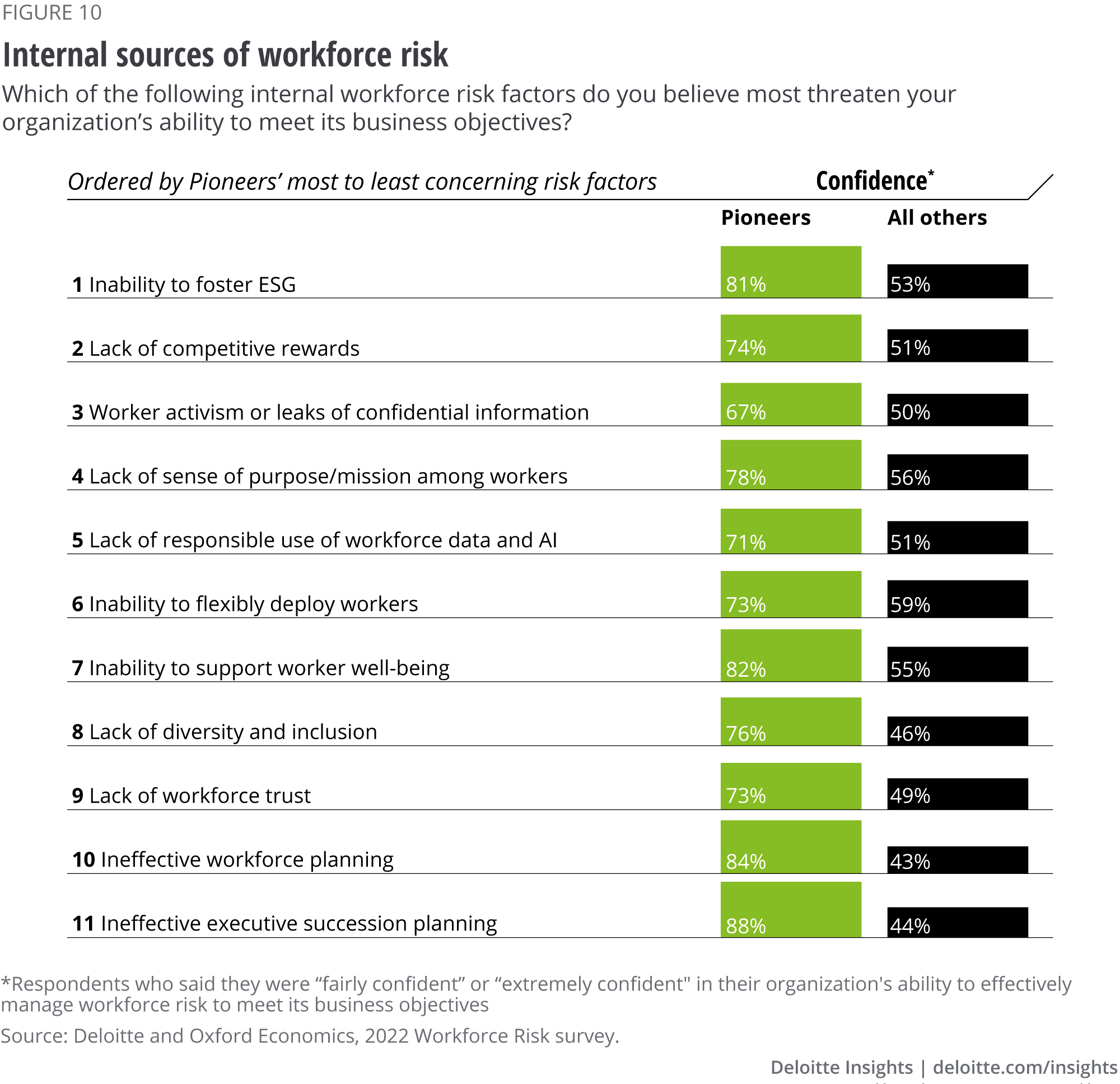

We asked respondents to identify the types of workforce risk they perceive as challenges to their organization’s ability to achieve success. When presented with a list of possible sources of workforce risk (across 17 external and 11 internal sources) and asked to rank the five biggest risks, issues such as reducing turnover and increasing wages were seldom cited despite recent focus by the media, investors, and workers. On average, across all categories, Pioneers were twice as likely to be “extremely confident” in their organization’s ability to manage risks than their peers.

Respondents were most concerned with risks likely to damage their organization’s brand and reputation. That fixation on perception is notable, considering leaders typically have more agency to influence their turnover rates, wages, and workforce’s skill gaps than they do to manage public perception of their brand or reputation. The vast majority (91%) of respondents spend less than 20% of their time managing workforce risk, indicating they may only be taking time to address surface-level workforce risk factors. However, Pioneers are beginning to buck this trend: They seem to have started to embrace a broader view of workforce risk and its impact on an organization’s outcomes. As a result, they feel better prepared than their peers to address the root causes of a variety of external and internal workforce risks (see sources of risk in figures 9 and 10).

External sources of workforce risk

The top-ranked external risks for survey respondents were those associated with the amplified voice of individuals potentially damaging their organization’s brand, and factors related to the location of their workforce such as political or economic turmoil in specific countries. Some of the most significant sources of external workforce risk reported by survey respondents are unpacked in more detail below (also, see figure 9).

- Amplified voice of individuals: With the rise of social media and the proliferation of media channels, the voices of investors, activists, and workers are more amplified than ever, enabling individuals to broadcast their personal concerns widely. As a result, Pioneers and non-Pioneers alike ranked activities that could damage their organizations’ brands and market reputation, such as customer complaints or negative media attention, as their top concern.

- Skills and talent availability: Both Pioneers and all other survey respondents ranked their ability to reskill and upskill existing workers as a top (No. 4) concern. However, Pioneers seem to closely associate such issues with their strategic prospects, ranking their ability to access talent as the second-highest challenge to achieving their business objectives.

- Changing expectations of the workforce: As attitudes around social responsibility, purpose, living wage, and work-life balance continue to evolve, many workers have begun to expect more from their employers. While such considerations may be high priority for a growing proportion of workers—particularly Gen Z and Millennials8—most companies do not appear to be concerned. In fact, both Pioneers and their counterparts responded that they were least concerned about this category of external risk over any other.

- Location of workforce: With the rise of alternative work models, such as remote and hybrid work, all respondents shared a high level of concern regarding the location of their workforce. Recent studies indicate that 75% of Millennials and Gen Z9 and 65% of women10 prefer hybrid work arrangements, and this trend is considered likely to grow over time. Decades of globalization have brought their own risks to supply chains and workforces alike. Pioneers were nearly 60% more likely than their peers to be confident in their ability to manage challenges related to the location of critical workforce segments

- Regulations and compliance: Compliance with regulatory and administrative standards, changes to human capital reporting requirements, and government sanctions or intervention: These are just some of the factors associated with regulations. While survey respondents were not particularly concerned with such factors, the majority of Pioneers felt confident in managing those challenges while the majority of their peers did not.

Internal sources of workforce risk

Pioneers and non-Pioneers both ranked worker activism or leaks in confidential information as well as adopting environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices as top sources of internal risk. Some important sources of external workforce risk reported by survey respondents are provided below and in figure 10.

- Culture, trust, and mission: Most Gen Z and Millennials responding to a recent Deloitte Global study want their organization’s purpose and mission to align with their personal values.11 The majority of both Pioneers (78%) and their peers (56%) feel very or extremely confident in their ability to deliver an organizational purpose embraced by their workforce. Yet fewer than 40% of respondents in either category report that their C-suite and board provide governance and oversight on such issues; roughly 25% reported tracking belonging and inclusion. Meanwhile, another Deloitte study recently revealed that 66% of business executives face increasing pressure to show their commitment to creating organizational purpose for workers, shareholders, and society.12 Not only can a shared sense of purpose improve an organization’s brand and reputation, it can also help build workforce trust.

- Workforce planning and deployment: To perform at their best and meet evolving business needs, organizations should have a workforce planning process that helps establish the right people in the right place at the right time, for the right cost. To accomplish that, they should plan for succession, cultivate new talent pipelines, and deploy workers against emerging business priorities fluidly. Proper application of such practices can have a dramatic impact. One study found that companies that can quickly reposition appropriate talent into critical roles were more than twice as likely to outpace competitors on total returns to shareholders.13 However, executive-level succession planning and effective workforce planning were among the areas of least concern across all respondents.

- Environmental, social, and governance (ESG), and diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI): From college activism and social media hashtags to boardroom discussions and government regulations, there is a great deal of attention paid to ESG and DEI. Pioneers cited their ability to foster ESG and sustainable business practices as their No. 1 internal risk concern, while non-Pioneers ranked it second. When it comes to creating a diverse and inclusive culture, non-Pioneers rated this area among the bottom three in their confidence to achieve it.

- Compensation, benefits, and well-being: Historical macro trends and tight labor markets have added to the competition for talent related to compensation, benefits, flexibility, and work-life balance. Pioneers remain confident in their ability to manage risks associated with overall worker well-being (82%) and providing competitive compensation and benefits (74%), while roughly half of all others were confident in their ability to do so.

- Data, technology, and metrics: Companies can collect vast amounts of data from their workers and customers more easily than ever, transforming it into insights with the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and advanced analytics. Although this can benefit workers and organizations alike, if organizations do not take a responsible approach to workforce data and technology, they may be at risk of data privacy and security breaches, erosion of workforce trust, and financial or regulatory penalties. Pioneers not only ranked leaks of confidential information and the responsible use of workforce data and AI among their top concerns, they were also the least confident in managing this internal risk.

Actions to aid in understanding workforce risk

- Clearly define workforce risk and its potential impact on financial, operational, reputation and brand, and regulatory and compliance outcomes.

- Spread knowledge of workforce risk broadly across the enterprise and empower leaders at all levels to take responsibility and accountability to help manage it proactively.

- Prioritize external and internal sources of risk based on the organization’s specific needs and levels of exposure.

Measure and monitor workforce risk

The transformation journey ...

From: Lagging indicators and short-term metrics of workforce risk gathered from traditional data sources, compiled without or with limited transparency

To: Predictive leading indicators and longer-term projections of workforce risk gathered from both traditional and new data sources, and used ethically and transparently

Defining the right metrics to measure

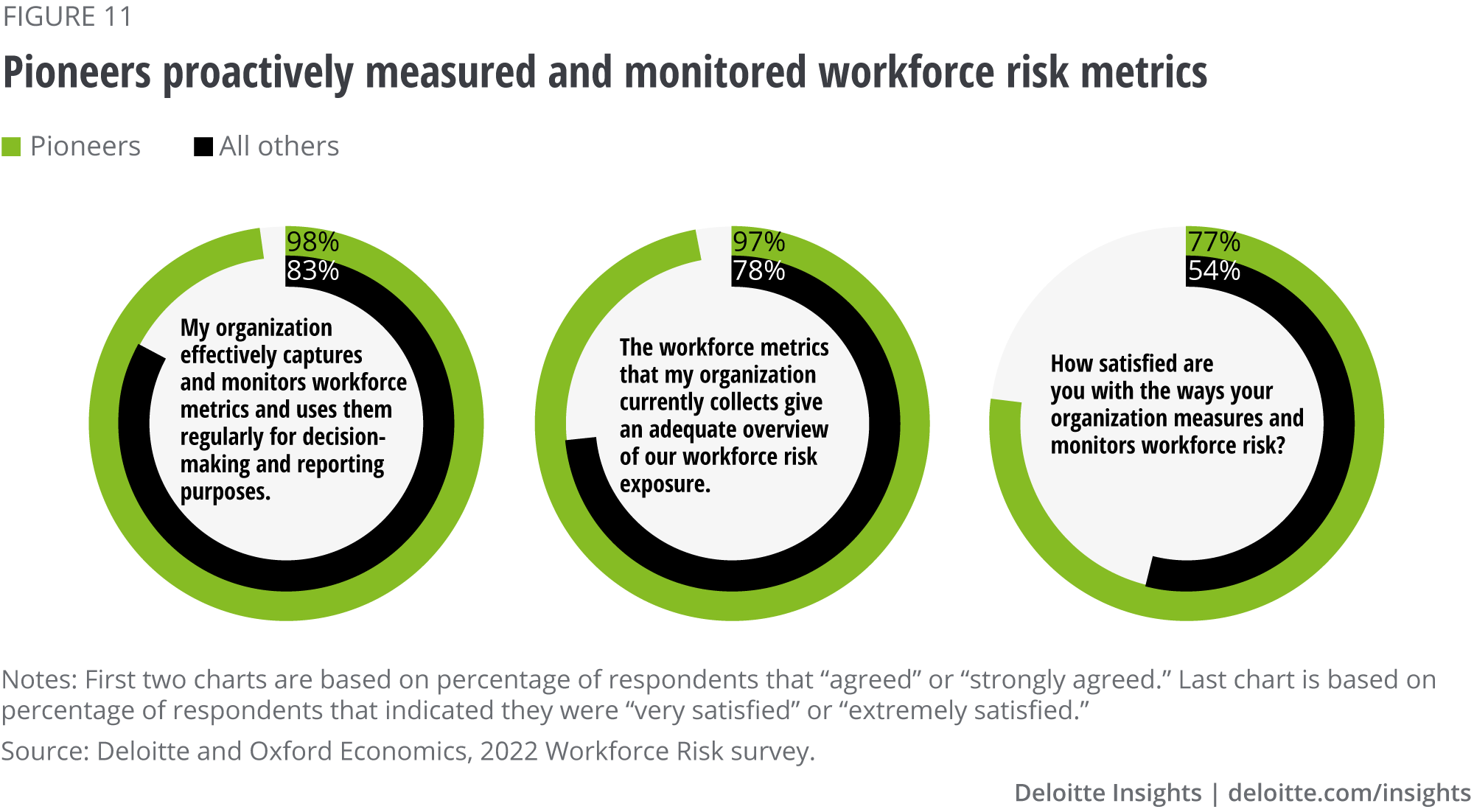

Effectively managing workforce risk means that organizations should have the ability to measure and monitor it. Pioneers were over 40% more likely than their peers to be satisfied with their ability to do so. They also reported they were more likely to use new technologies and sources of workforce data to measure and monitor workforce risk than non-Pioneers.

Pioneers also stood out in their ability to leverage the data they collect to drive decision-making and use it to provide an overview of their risk exposure (figure 11).

Pioneers remained more confident in their ability to track specific workforce-related metrics. Where most other respondents measured only four out of 12 workforce risk metrics tested and just 44% strongly believed they provide an adequate view of exposure, Pioneers captured more metrics and felt they were more effective at measuring and monitoring workforce risk (figure 11).

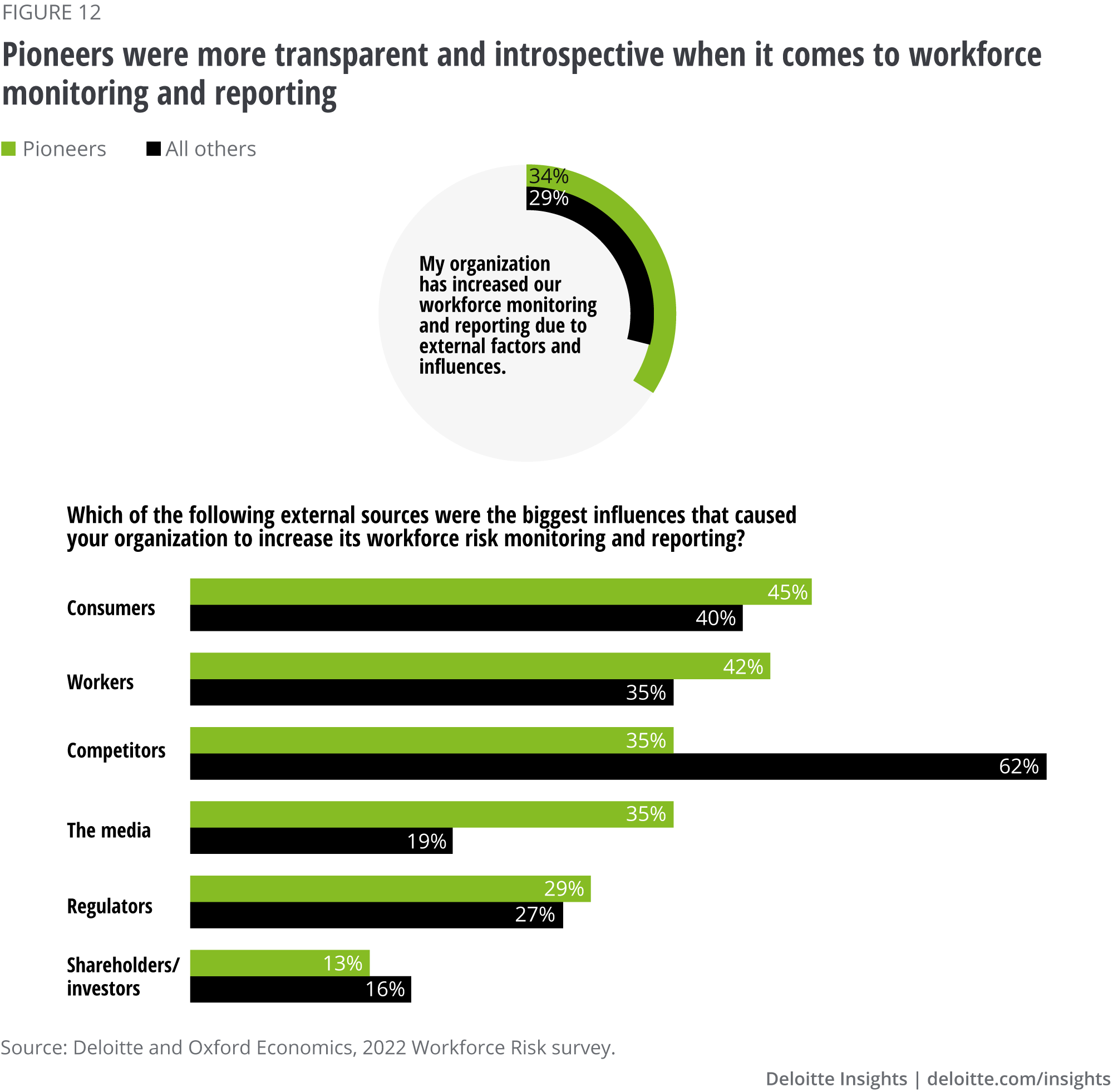

Being transparent and introspective

Influenced most by consumer and workforce expectations, nearly all Pioneers (99%) reported they provide regulators with considerably more workforce data than is required. Pioneers were also marginally more likely than their counterparts to increase their reporting based on what is required by regulators, and far less likely to change their approach based on the practices of their competitors (figure 12).

Many chief financial officers are currently tasked with representing and reporting their company’s data in response to new regulations requiring US companies to disclose their “human capital resources.” For example, JetBlue Airways Corp. used this requirement as an opportunity to voluntarily disclose more information on human capital–related risks than what is required or was disclosed by their peers and competitors: In its latest social impact report, JetBlue disclosed various workforce data describing hiring demographics and overall attrition and turnover rates, along with DEI metrics that break down workforce representation by gender, race, and ethnicity.14

Pioneers’ transparent, introspective, and future-oriented approach to monitoring and reporting workforce risk may represent the path forward. These practices could help organizations remain compliant and help predict risk, as well as increase worker and external trust in the organization. Based on their self-reporting, Pioneers largely felt more prepared to manage trust-related issues among the workforce than other respondents.

One way Genpact pursues such a course is by gathering data from its workforce. Instead of relying on conventional employee surveys to understand their attitudes, Genpact uses a suite of internal tools that regularly check in on employees to learn what is or isn’t working well and to gauge their mood and sentiment as a leading indicator of workforce retention. To try to reduce the risk of attrition, the company has now linked 10% of the CEO’s and top 150 leaders’ bonuses to the workforce’s “mood” score. It also uses organizational network analyses to help predict attrition before it happens.15

Actions to assist in measuring and monitoring workforce risk

- Identify leading or predictive indicators of the most important workforce risks, and collect data on them to help prompt intervention.

- Develop predictive analytics or AI capabilities that analyze workforce data to help inform decision-making.

- Incorporate robust and varied internal data about workforce risks, with particular attention paid to new sources of real-time data.

- Review your workforce data and determine which data would be helpful to voluntarily disclose to the public, why, and in what form (for example, annual reports, earnings calls, SEC 10-K and 10-Q filings).

Manage and govern workforce risk

The transformation journey ...

From: Reacting to workforce risks once they become a problem

To: Identifying and mitigating workforce risks before they occur by implementing holistic strategies to combat risk and expanding board and C-suite oversight.

Managing and mitigating workforce risk

By continuously measuring and monitoring workforce risk, organizations can spot and act on potential problems before they have material impact on the reputation, operations, or financial performance of the organization. It’s important to develop management practices that enable organizations to act confidently and in a timely fashion, thereby heading off workforce risk. Tools and techniques such as scenario planning, real options, and using AI to alert managers of potential emerging risks can all help (see the sidebar “Tools and techniques for managing workforce risk” for more details).

Most Pioneers recognize that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to managing workforce risk. They were 44% more likely than others to adjust their workforce risk management practices to account for various worker segments and types of working arrangements that exist. These segments include, but are not limited to, workers with different skill levels, from various backgrounds (different generations, cultures, ethnicities, genders, sexual orientations), external workers, remote and hybrid workers, critical workers, executives, their successors, and more.

Take external workers, for example. Many organizations increasingly rely on contingent or highly skilled gig workers to perform essential work, but they often haven’t adapted their management practices to account for the unique risks that this workforce segment can often pose. While using external workers can help organizations access urgently needed skills or optimize costs, it can also increase risk exposure such as co-employment or other regulatory risks, or risks to an organization’s brand and reputation if external workers aren’t trained to interact with customers appropriately. A recent Deloitte study found that only 22% of surveyed organizations were "very effective” in defining and managing a workforce comprising both internal and external workers.16

Tools and techniques to help manage workforce risk

The size, scope, and diversity of today’s workforces can be a complicating factor in managing at scale. To do so effectively, leading organizations often turn to modern solutions to evolve their risk management techniques and approaches.

AI tools

Organizations can infuse technology into processes that provide line managers with tools and approaches they can use to better understand and manage workforce risk. For example, when Genpact’s Amber AI tool flags that someone is likely to leave, the company has a series of practices to help managers understand why employees may feel unsatisfied and try to retain them. This includes encouraging managers to put employees on an internal learning platform to support their development, as well as suggesting when it might be a good time to move a person to another function based on an analysis of trends in employee performance, role tenure, and engagement levels.17

Scenario planning

Organizations can leverage data to conduct scenario planning and help improve decision-making before a risk ever manifests. Gard, a Norway-based global insurance provider, actively conducts scenario planning for business risks, including those affecting the workforce. The company identifies a broad list of potential risks related to socioeconomics, environment, geopolitics, and technology, then seeks input from both the board and managers on which they believe are most likely to manifest. Gard then conducts scenario planning around these risks with cross-functional working groups to identify potential solutions.18 However, only 15% of C-suite and board members we surveyed say they conduct scenario planning as a way of managing workforce risk.

Real options

Organizations can apply techniques from other disciplines such as “real options,” an approach that encourages leaders to compare every incremental opportunity arising from their existing investments with the full range of opportunities open to them. Real options can serve as both a systematic framework and a strategic management tool. When labor demand and costs are uncertain, for example, organizations can consider real options to engage in flexible contracting, changing the way management thinks about and values opportunities. This could help an organization decide if an investment should be made to realize the payoff immediately or whether a project should be delayed to help maximize overall payoff. Workforce risks should also be considered in any strategy discussions and development, as well as in workforce planning.

Providing governance and oversight

We asked respondents to review 11 different areas of workforce risk and indicate in which areas their organization’s board or C-suite provided governance and oversight. Nearly 90% of respondents indicated their C-suites and boards oversee at most four of the 11 areas. Furthermore, only 40% of respondents indicated that their board members have expert-level knowledge of workforce-related risks. Leaders of Pioneers’ organizations seemed to provide governance and oversight across more workforce risk focus areas than their peers. In particular, Pioneers focused on longer-term factors—such as availability of skills and talent; corporate brand and reputation; measuring, monitoring, and reporting of workforce-related metrics; expectations of the workforce, shareholders, and stakeholders; and ESG and DEI initiatives—25% more frequently than other respondents on average. Conversely, non-Pioneers continued to focus on traditional workforce-related factors such as executive-level succession planning and workforce planning 31% more than Pioneers (figure 13).

As mentioned earlier, our research suggests that there may be limited involvement at the board level when it comes to overseeing workforce-related issues. Some leading organizations have started to take action by expanding their compensation committee’s ambit to include oversight of the workforce as a whole and the related impact on risk, strategy, and operations. For example, Allstate and Levi Strauss have established “compensation and human capital committees.” The scope of these committees includes, but is not limited to, oversight of policies and strategies regarding culture, recruiting, retention, career development and progression, talent planning, and diversity and inclusion.19

Other Pioneers have taken the approach of embedding workforce risk across multiple committees. For example, Signet Jewelers recently centralized much of workforce risk oversight into its newly expanded Human Capital and Compensation Committee. This committee oversees a wide range of human capital management efforts including culture, DEI, executive compensation programs, benefits and well-being strategy, talent management (attraction, development, and retention), performance management, and succession planning.20

Actions to help manage and mitigate workforce risk

- Adopt new strategies and innovative management approaches that account for more diverse workforce ecosystems of internal and external contributors.

- Establish responsibility and oversight for workforce risk that starts at the board level and cascades across the C-suite down to line managers to help manage emerging risks.

Toward the next frontier of workforce risk management

While Pioneers seem to be taking steps in the right direction, our research strongly suggests that all respondents have opportunities to improve their effective management of workforce risk. Leaders who do not prioritize broader strategies for managing workforce risk could find themselves at odds with board members, asset managers, influential shareholders, and regulators, all of whom seem to be increasingly interested in how such risks are managed.

If people are truly an organization’s greatest asset—and from a financial perspective they are, comprising as much as 70% of total expenditure21—it should be an imperative for C-suites and boards to clearly define their company’s workforce risk profile, refine the definition frequently, and continuously develop strategies to mitigate it. Those that lag could soon find themselves unable to keep pace with their competitors in the never-ending war for talent.