Overcoming biopharma's trust deficit

Why people mistrust the biopharma industry—and what to do about it

Executive summary

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy has put a spotlight on an issue well known to biopharmaceutical manufacturers—trust. While many people do trust the drugs they take, numerous consumer polls have shown that the biopharma industry ranks as one of the least trusted—although that has been improving during the pandemic.1 Trust matters for companies—from influencing their chances of gaining and maintaining customers to their ability to recruit talent that is attracted to a shared goal of improving health care outcomes. Consumer trust also gives biopharma the incentive to innovate and provides support for the industry’s contributions and mission to provide valuable, life-saving therapies. Trust is critical: companies should make deliberate strategic choices to build trust and to enable quick responses when challenges arise.

In January 2021, Deloitte’s US and UK Centers for Health Solutions conducted consumer research in four countries—the United States, United Kingdom, India, and South Africa. Some of the key questions we sought to answer were:

- What does “trust” mean to consumers and why is it important?

- What are the reasons for distrust?

- How much do consumers in the United States, United Kingdom, India, and South Africa trust biopharma companies, and what issues does biopharma face in each country when it comes to trust?

- How can companies build trust among consumers?

Across all four countries, focus group participants were generally in agreement on most questions, although we highlight some where there were large differences.

In discussions with biopharma public relations professionals, we heard strong support for companies investing in opportunities to build trust with patients and the public using a variety of approaches that are consistent, responsive, and build upon each other. These include:

- Elevating—and humanizing—leaders in the industry, especially CEOs, but also chief scientific officers and other scientists who work for the companies and have a strong sense of purpose

- Developing partnerships with patient groups, doctors, nurses and pharmacists, and other organizations that can help provide useful information about products, as well as to share what companies are doing to make drugs accessible.

- Designing experiences that proactively communicate and quickly respond to consumer complaints—in a timely fashion and through appropriate channels—in ways that comply with regulations

- Devoting more effort to support communications that explain complex science and trials to the public

- Calling out “bad actors” collectively in a timely manner to demonstrate accountability for behaviors or practices that are not representative of how the rest of the industry wants to operate

Methodology

In late January 2021, Deloitte’s US and UK Centers for Health Solutions conducted four separate, anonymous, digital focus group discussions using a convenience sample of 60 consumers in each of the following countries: the United States, United Kingdom, India, and South Africa (total N=240). Each session was an hour long and was conducted in English. Participants were recruited through an established vendor using vetted panels.

We aimed for participant diversity in age, gender, race/ethnicity, educational achievement, and annual household income. However, our sample is not representative of each country’s population nor of these characteristics. Findings should be considered as providing qualitative insight, as would be typical of focus groups.

We asked participants a mix of questions, often requesting open-ended responses and then moving to multiple choice options, exploring the following themes:

- Consumers’ definitions of trust in organizations

- The reasons why consumers trust or distrust pharmaceutical drug companies

- What consumers think drug companies can do to increase trust

- Intentions to get COVID-19 vaccinations and reasons for vaccine hesitancy

In addition, we interviewed five, US-based public relations and communications professionals from the biopharma industry to understand their experience and insights around sustaining and improving consumers’ trust.

Understanding trust and why it matters

Defining trust

“Trust means that I would have full confidence in a product or person and that it would be reliable and trustworthy, and it would work effectively as promised.”

Trust is “our willingness to be vulnerable to the actions of others because we believe they have good intentions and will behave well toward us.”2 We are willing to put our trust in others because we have faith that they have our best interests at heart, will not abuse us, and will safeguard our interests—and that doing so will result in a better outcome for all.3

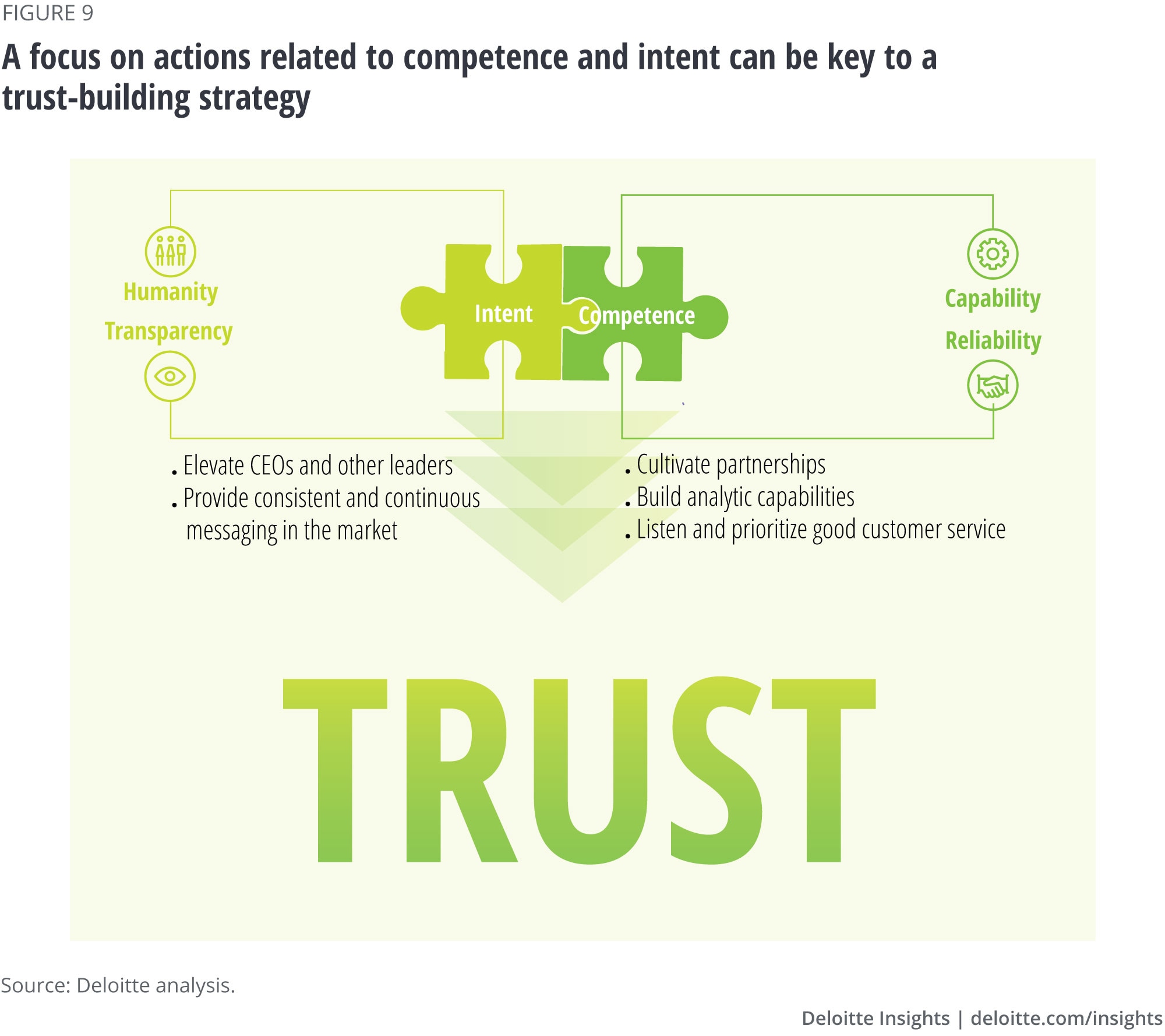

Organizations and leaders can build and maintain trust by acting with competence and intent.4 Competence refers to the ability to execute; to follow through on what you say you will do. Intent refers to the meaning behind an organization’s actions, taking decisive action from a place of genuine empathy and true care for the wants and needs of stakeholders.5

So, what does the word “trust” mean to participants in our focus groups? Across all four countries, the concepts were similar: Focus group participants used words such as “reliability,” “dependability,” and “having complete confidence in something,” when asked to describe what trust means to them. They said that trustworthy organizations actively respond to customer feedback, follow through on promises, and deliver high-quality goods and/or services. They also said that trustworthy companies openly share information and their business motives.

On the other hand, participants used terms such as “consumer data privacy issues,” “don’t deliver on promises,” and “low-quality products” to describe organizations they do not trust. Specific social media companies, e-commerce companies, some government organizations, and financial institutions were among those on top of people’s minds.

“Trust means to have faith in a person or company. That they won’t betray you.”

Trust matters—for consumer loyalty, for working with regulators and policymakers, and for attracting partnerships and talent

In general, trust drives customer loyalty; 62% of people who report highly trusting a brand buy almost exclusively from that brand over competitors in the same category.6 Savvy customers pay attention to the companies they are buying from and expect them to be ethical and socially responsible.7 If not, they may seek alternatives, which can ultimately impact the bottom line.

For biopharma, maintaining reputational integrity within the health care ecosystem among all stakeholders—consumers, health care providers, regulators, NGOs—is critical. First, trust is essential for recognition of the value the industry brings to society in the way of significant improvements in life expectancy and health outcomes. This recognition can be hard-won, since health care is viewed as a necessity, not a luxury. It can also call biopharma’s business motives into question, whereas other industries such as consumer technology, which produce products that are not required for good health, routinely post large profits without raising eyebrows.

Second, many aspects of R&D and patient support programs involve partnerships with entities such as nonprofit organizations and academic institutions, and there is competition for these partnerships. If a company’s reputational value is high, it’s more likely to be someone’s first choice as a partner. The same is true for relationships with regulators and policymakers. Strong reputational value could mean a stronger working relationship with regulators, leading to a shared understanding of goals and next steps as well as stronger public support, with less call for changes to payment and other policies that might undermine companies’ ability to create value and innovate.

Finally, trust improves high-quality talent recruitment and retention. Employees who highly trust their employer are about half as likely to seek new job opportunities,8 which in turn can boost reputational value in addition to innovative capabilities.

Understanding trust within the health care system

Physicians and their associations are the most trusted source of health-related information across all four countries

Health care consumers are more educated than ever, owing to copious information available on the internet. They are asking questions about medicines prescribed to them and are aware of the manufacturers of those medicines; 51% of our focus group participants said they take a medicine and know who makes it. Consumers are using websites such as WebdMD (United States), MedIndia, Babylon (United Kingdom), and Africa Health as sources of health-related information and are sharing their experiences with products and service providers via social media and other patient channels.

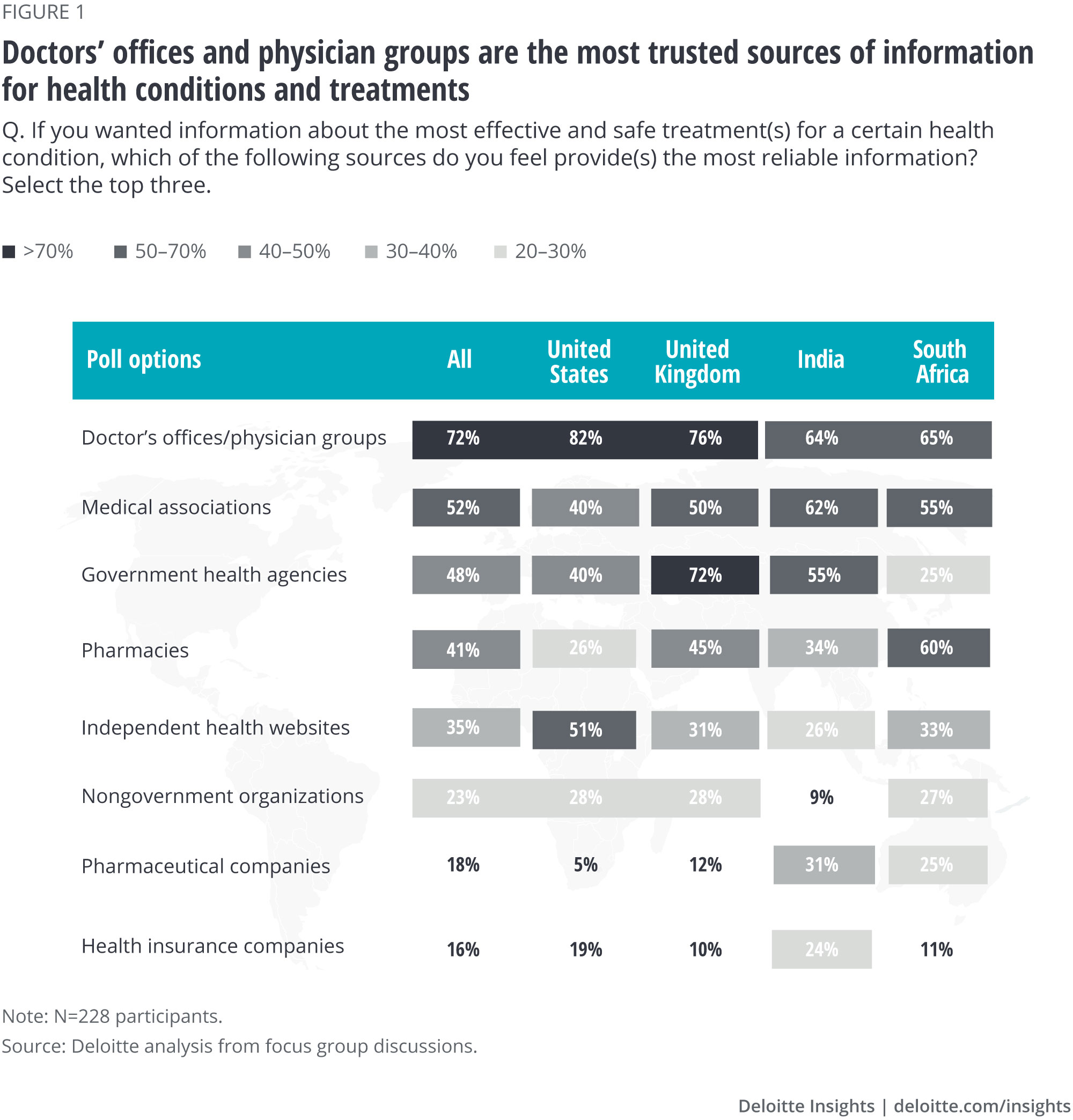

Not surprisingly, 72% of participants in our focus groups chose doctors’ offices and physician groups—and the National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom—as their most trusted sources of information for health conditions and treatments. This could be because of the personalized experience of patients when visiting the doctor one on one as well as the personal, trusting relationship they have with their physicians.

Participants ranked medical associations and government health agencies in the No. 2 and No. 3 spots, respectively, on the most trusted entities list. Interestingly, participants in South Africa also rated pharmacies, which are often used as points of primary care among certain groups, as trustworthy sources of information (ranked No. 2).

Participants ranked biopharma companies near the bottom of the list of eight possibilities in all countries—except in India (ranked No. 5), where positive sentiment toward national biopharma manufacturers, particularly those involved in the making of COVID-19 vaccines, appears to be stronger. Health insurance companies and nongovernmental organizations rounded out the list.

Consumers view biopharma brands favorably

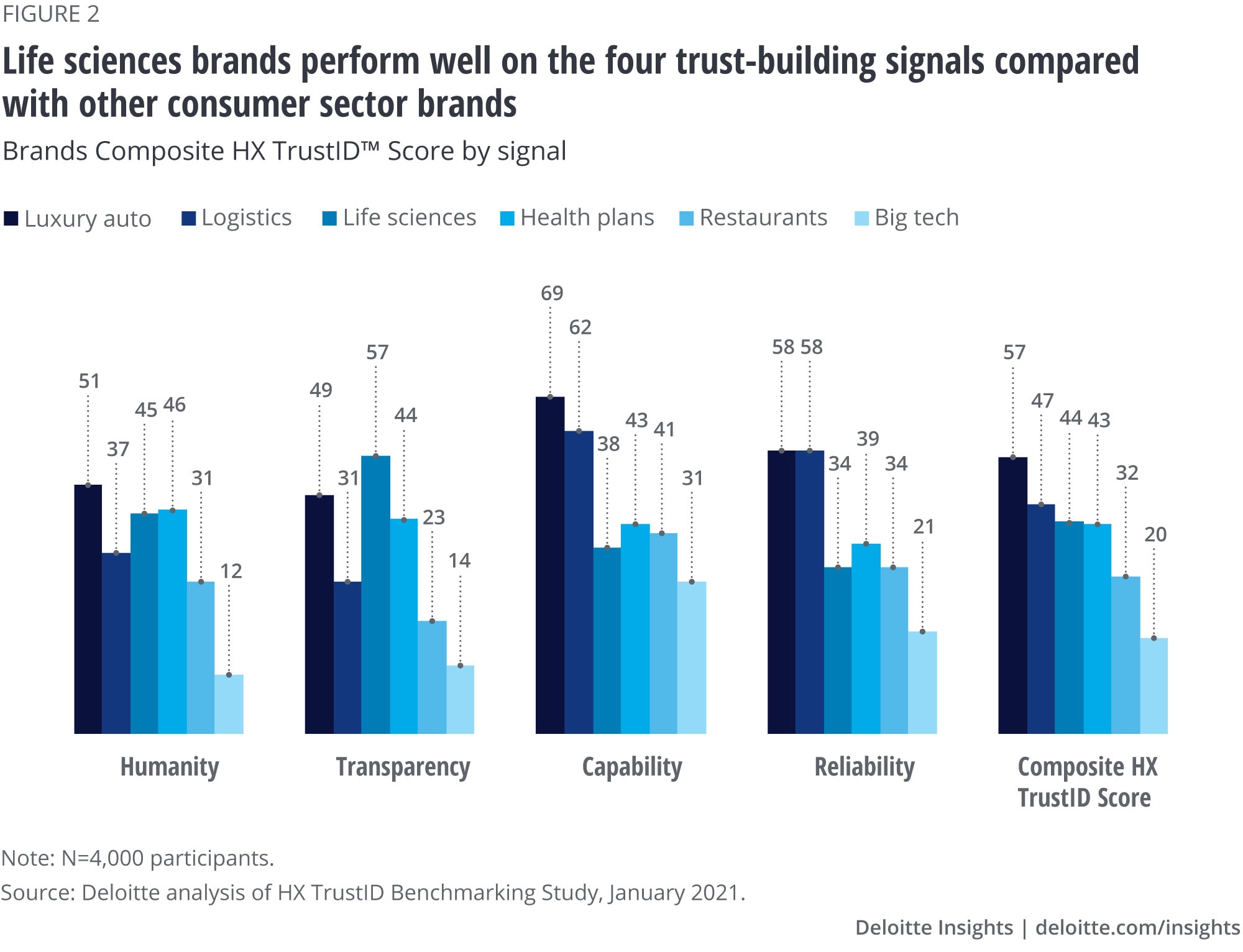

Deloitte research indicates that when a biopharma company demonstrates certain signals, consumers will view their brand more favorably. These four trust-building signals are humanity, transparency, capability, and reliability.

According to a recent Deloitte HX TrustID™ survey of 4,000 consumer branded product users in the United States—covering sectors such a life sciences, health care, technology, consumer goods, retail, automotive and transportation, travel and hospitality, and government—only luxury cars and logistics/shipping companies rated higher on trust than biopharma companies across the four signals of trust-building activities (figure 2).9

This may be because consumers were willing to say that they trust specific product brands more than an industry as a whole; however, the trend was similar among product nonusers, too.

Consumer sentiment around trust for pharmaceutical drug companies is divided

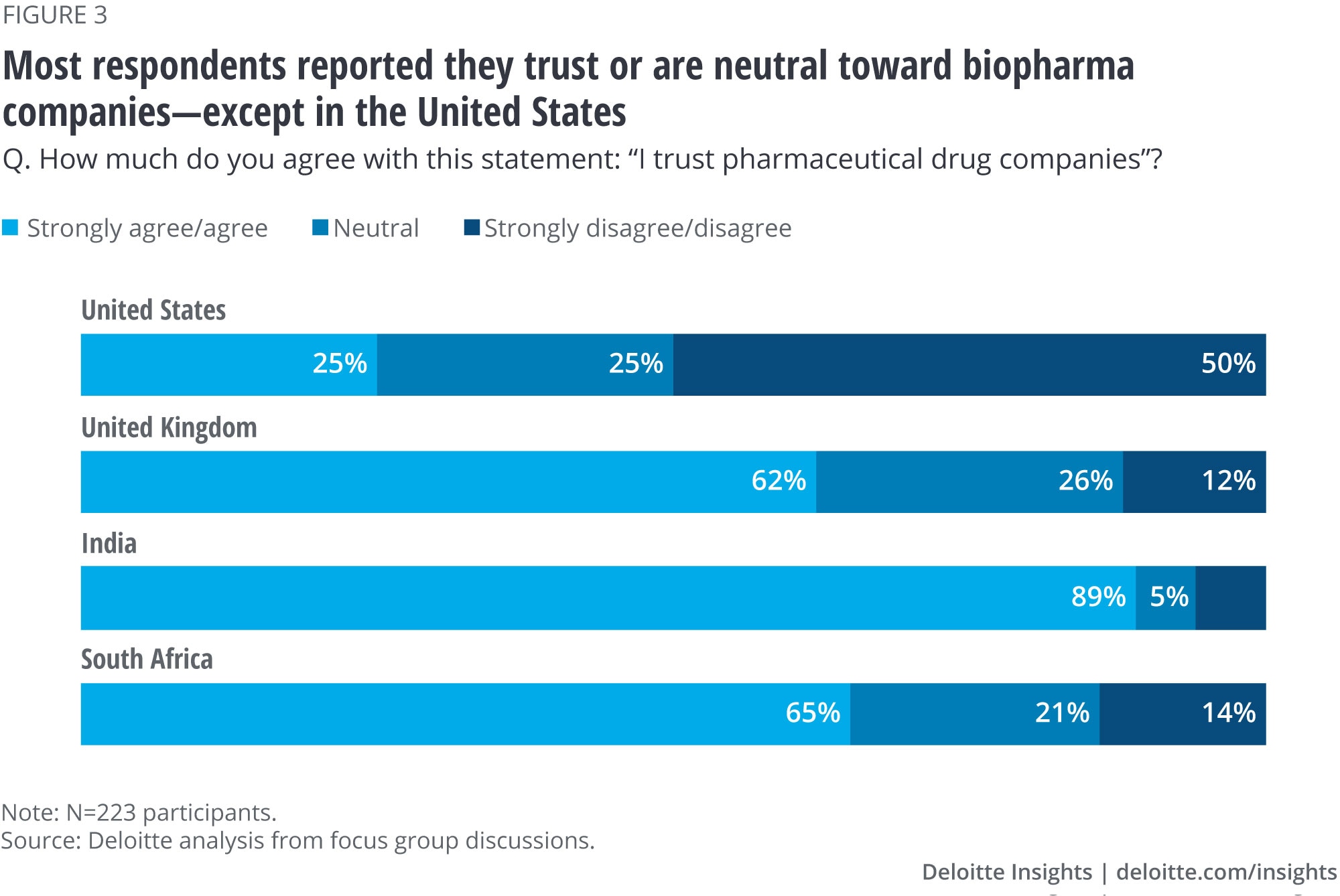

Across all four countries, 80% of focus group participants said they trust biopharma companies or are neutral toward them. As previously mentioned, we found the strongest sentiments of trust in India (89%) and agreement in both the United Kingdom and South Africa (62% and 65%, respectively) (figure 3). Conversely, 50% of participants in the United States said they don’t trust biopharma companies. One possible explanation is that public hearings and the press have exposed the circumstances of people who cannot afford critical drugs due to their price. Additionally, although direct-to-consumer advertising may create awareness of certain therapies among target populations, the broader public may focus on the sheer volume of advertisements as well as the long list of side effects that are read off.

To learn more about people’s views, we asked participants to explain why they agreed or disagreed with the statement “I trust pharmaceutical drug companies.” Those who agreed used words such as “specialized,” “invested,” and “responsible” to describe how they felt. Participants noted that biopharma is a heavily regulated industry that invests significantly in R&D, one that makes sure drugs are tested and safe for human use, and that it acts for the good of mankind.

“Pharma companies are doing a great service by investing in R&D and developing products for the eradication of diseases.”

However, about 20% of participants across all four countries disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement. They used terms such as “profit-making,” “harmful,” and “get you dependent on a product,” to express their distrust, and cited a focus on profit-making, high prices for medicines, and lack of transparencyabout how drugs are developed as their top reasons. One participant in South Africa mentioned that pharma companies focus more on “developing drugs for symptom management rather than providing a cure for the underlying problem.”

“At the end of the day, they want to make a profit, so they get you to be dependent on their products rather than providing a cure.”

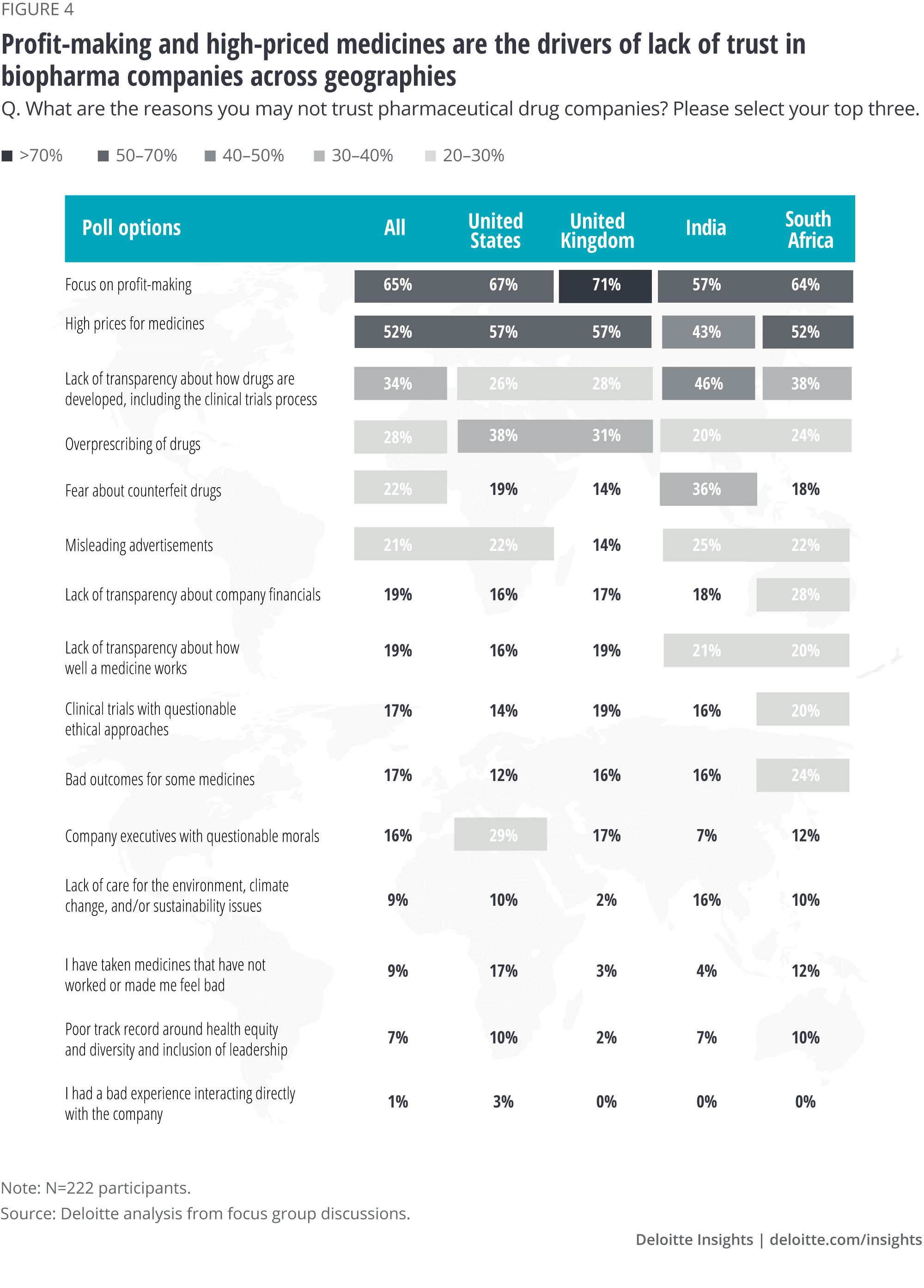

When participants had to choose from a list of reasons why they may not trust biopharma companies, a few other differences were revealed between the four focus groups (figure 4):

- In the United States, the overprescribing of drugs ranked No. 3—likely a reference to the opioid crisis. Overprescribing was also noted as an issue in the United Kingdom.

- Also, in the United States, 29% of participants cited the questionable moral integrity of biopharma executives as a point of contention, while 28% of South African participants said that lack of transparency around company financials was bothersome.

- In India, the fear of counterfeit drugs was a major concern—36% of participants cited this as an issue.

“Profiting from illness is a tough subject but I appreciate that if they didn't invest millions in research, then we wouldn't have had any new treatments such as the vaccine for COVID.”

Public relations professionals offered some explanations for these sentiments. They highlighted that biopharma is at a disadvantage given that, unlike hospitals, they are typically not directly involved with patient care delivery and are therefore disconnected from the patient experience. They also said that biopharma has historically not been able to effectively articulate how long and expensive the R&D process can be—nor that biopharma is not solely responsible for the ultimate cost of drugs—to provide good context for drug pricing. They also noted that stakeholders may not appreciate the overall value of therapies in the context of total cost of care and outcomes.

R&D is a complex, multiyear endeavor with many failures and learnings—how it shapes the investments made by companies and required financial returns to pay its staff and investors is difficult to explain. Pricing is also complicated and poorly understood by the public, which adds fuel to the fire. It is worth noting that we did not probe what the term “price transparency” means to our focus groups participants—this could be a future point of study.

How much exposure do patients have to drug costs?

People in the United States have different sources of health coverage and some are uninsured. Some individuals are exposed to high out-of-pocket costs for drugs, even if they have coverage because of benefit designs such as tiered formularies and large deductibles. There is no government or other central process for reviewing drug prices, but private plans do negotiate over payment rates with drug companies.

Most people in the United Kingdom access their health care through the NHS. Prescription drugs are provided at the point of care at a set charge; however around 90% of prescriptions are exempt from charges. About 10% of the population carries private insurance to gain faster access to elective care.10

In India, less than 20% of people are covered by public or private health insurance. Most people pay for medical care and pharmaceuticals out of pocket.11 Despite drugs being cheaper in India than in most other countries and despite price controls on many drugs, there is still price variation. The financial burden can be significant, especially when taking total income into account.12

Health care in South Africa varies from basic primary care, which is offered for free, to specialized care services offered in both the public and private sectors.13 Health care financing is mainly through private health insurance (medical schemes) and direct out-of-pocket payments.14 In terms of drug pricing, South Africa has the single exit price (SEP) mechanism, which sets the price at which a prescription drug maker must sell to all pharmacies. Out-of-pocket prescription expenses are estimated at about 8% as a whole; for those with private insurance, it is about 33%.

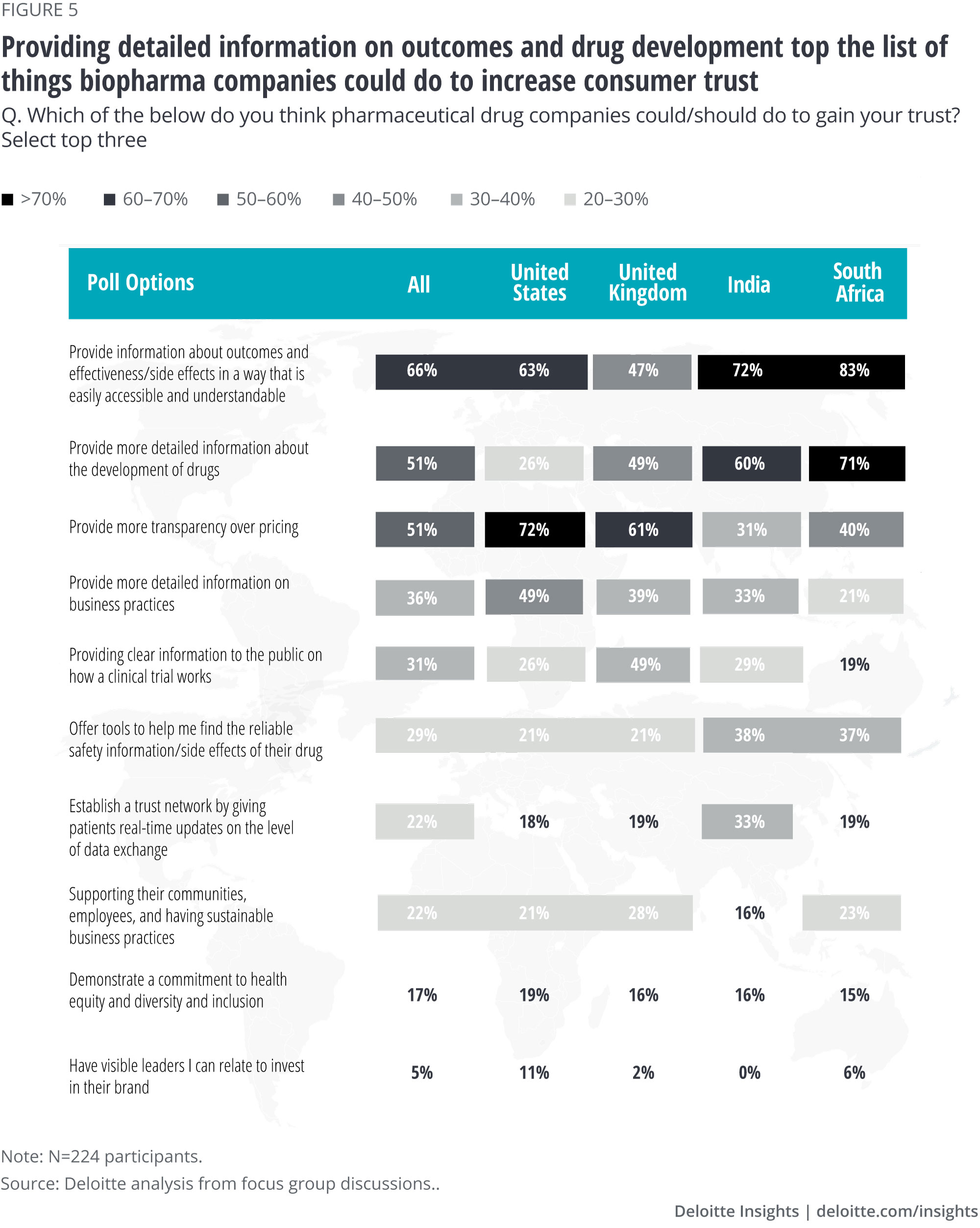

We also asked participants to tell us what biopharma could do to help gain their trust (figure 5).

- Generally, participants told us that they’d like to see easily understandable information related to drug effectiveness/side effects (66%), how drugs are developed (51%), and provide more transparency over pricing (51%). They were also interested in more information on business practices (36%).

- Participants in India and South Africa said they would like to see tools or data exchanges related to drug safety information (38% and 37%, respectively). South African and UK participants were interested in supporting sustainable business practices (23% and 28%, respectively), while US participants cited a commitment to health equity, diversity, and inclusion as a possible driver of trust.

- Interestingly, “having a visible leader” ranked lowest across all countries—we’ll come back to this important point later.

COVID-19 and trust in pharma

Most focus group participants said they didn’t think that development of COVID-19 vaccines has improved their views on pharma; however, larger, longitudinal surveys show improvements in trust through the pandemic

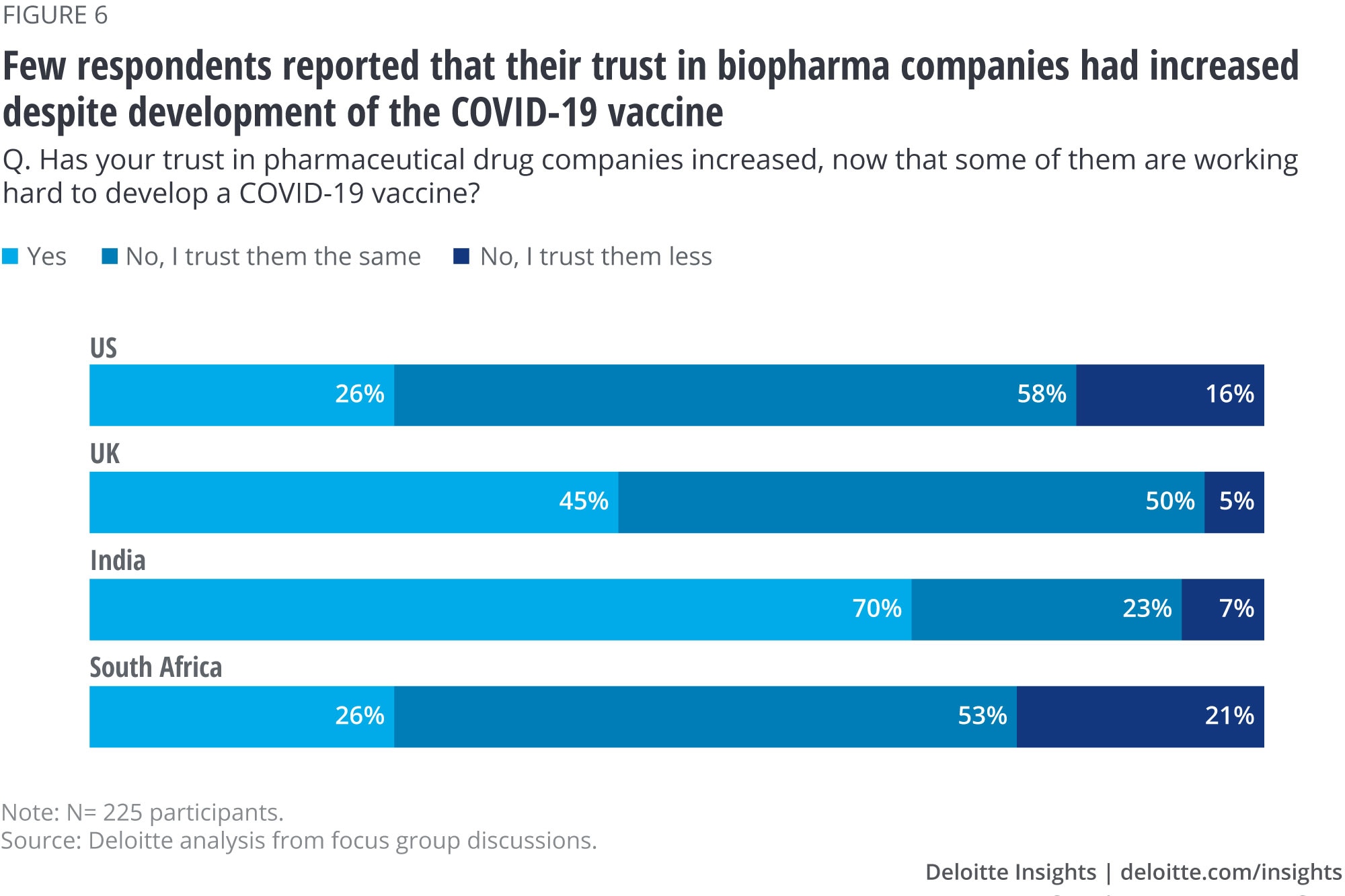

Most people are hoping that the biopharma industry can help forge a path back to normalcy from the significant disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic. In less than a year, the industry has developed vaccines and therapies that are effective at preventing and treating COVID-19 infection. According to a new report from Edelman, sentiment toward biopharma has improved since 2018, likely due to the industry’s contribution to the greater good.15

But relatively few participants in our survey—26% in the United States, 45% in the United Kingdom, and 26% in South Africa—reported that their feelings toward biopharma had improved (figure 6). However, 70% of participants in India said they had a more positive perception of the industry in light of vaccine development, which aligns with an overall higher trust in the industry among the country’s participants. Note that asking people whether their views have changed is different from sampling views of populations at different points in time—people may not recognize that a change in their opinion has occurred. Additionally, we did not probe to understand the full sentiment among those who said their view of biopharma has stayed the same. Also note that a small group of people reported their trust in biopharma has eroded as a result of vaccine development.

Participants attributed their lack of trust to the uncertainty around the cause of adverse events from experimental COVID-19 treatments and vaccines as well as media reports questioning their safety and efficacy during clinical trials. However, they did express appreciation of pharma companies’ efforts to collaborate among themselves and with government agencies to speed up the process of bringing the vaccines to market.

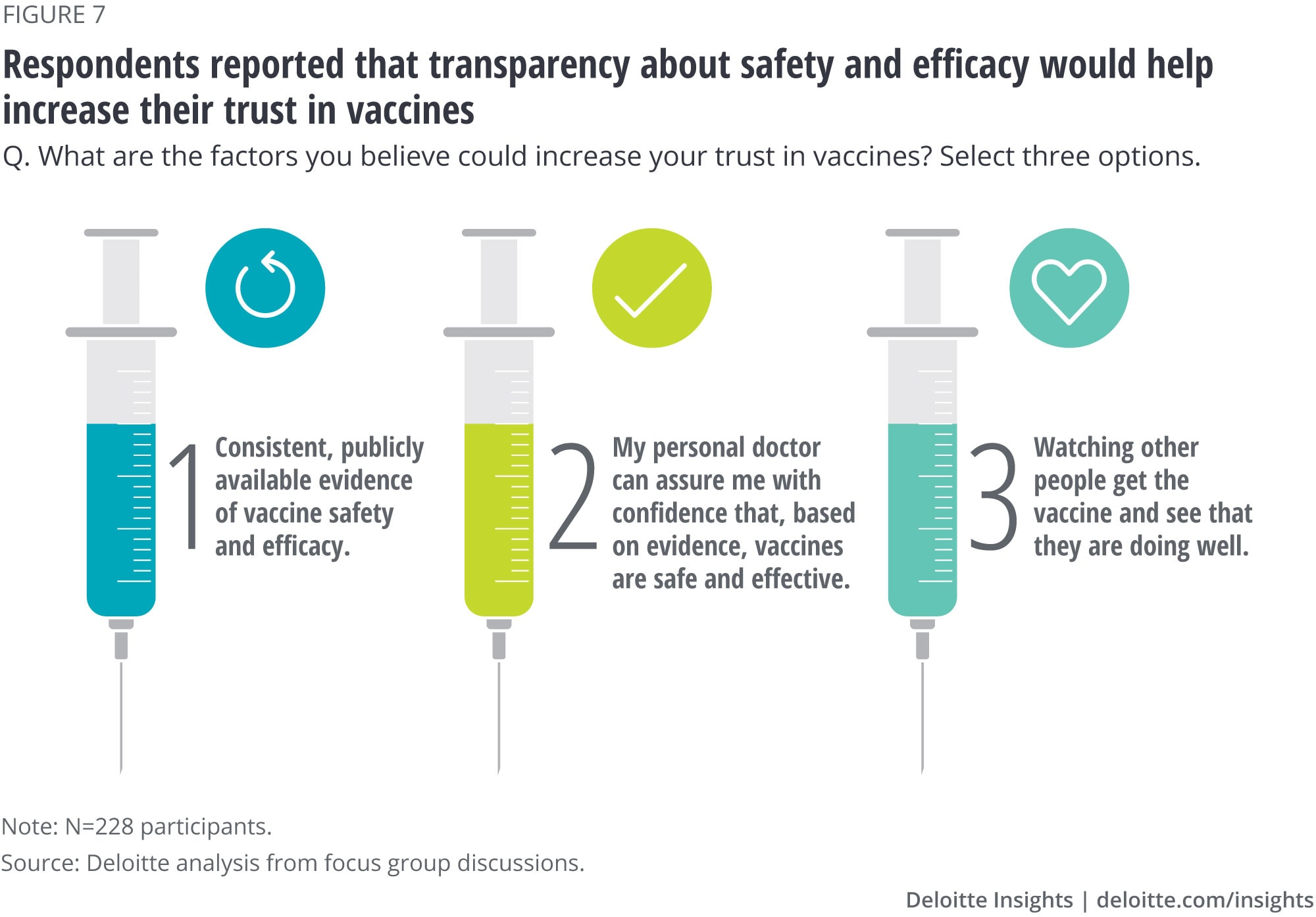

Consumers want pharma companies to be transparent about vaccines’ safety and efficacy

The pandemic has presented the biopharma industry with a unique opportunity to reconnect with consumers globally and rebuild trust by showcasing its innovative capabilities and value to society. When asked, survey participants said that more publicly available information about safety and efficacy(63%) as well as assurance from their personal doctor(55%)could increase their trust in vaccines (figure 7). Consumers are looking for biopharma companies to publicly highlight the side effects of the vaccines as well as provide transparency around clinical trials and the vaccine production process. Successful efforts in this vein will likely result in incremental improvements in trust in biopharma which can last even after the pandemic has ended.

Trust and the COVID-19 vaccine supply chain

While the production of a vaccine comes with its own challenges, studies suggest that trust is an underpinning factor for the successful launch, distribution, and acceptance of vaccines. Biopharma leaders should focus on areas such as product integrity, ethical distribution, and communicating transparently that can nurture trust among the public. Government leaders, regulators, and public health authorities should continue to be sensitive to the safety of the vaccines and the resources they need.16

“I will definitely take it, as it will be well-verified and will be available to us only after proper research has been done. I trust the pharmaceutical drugs companies and the government.”

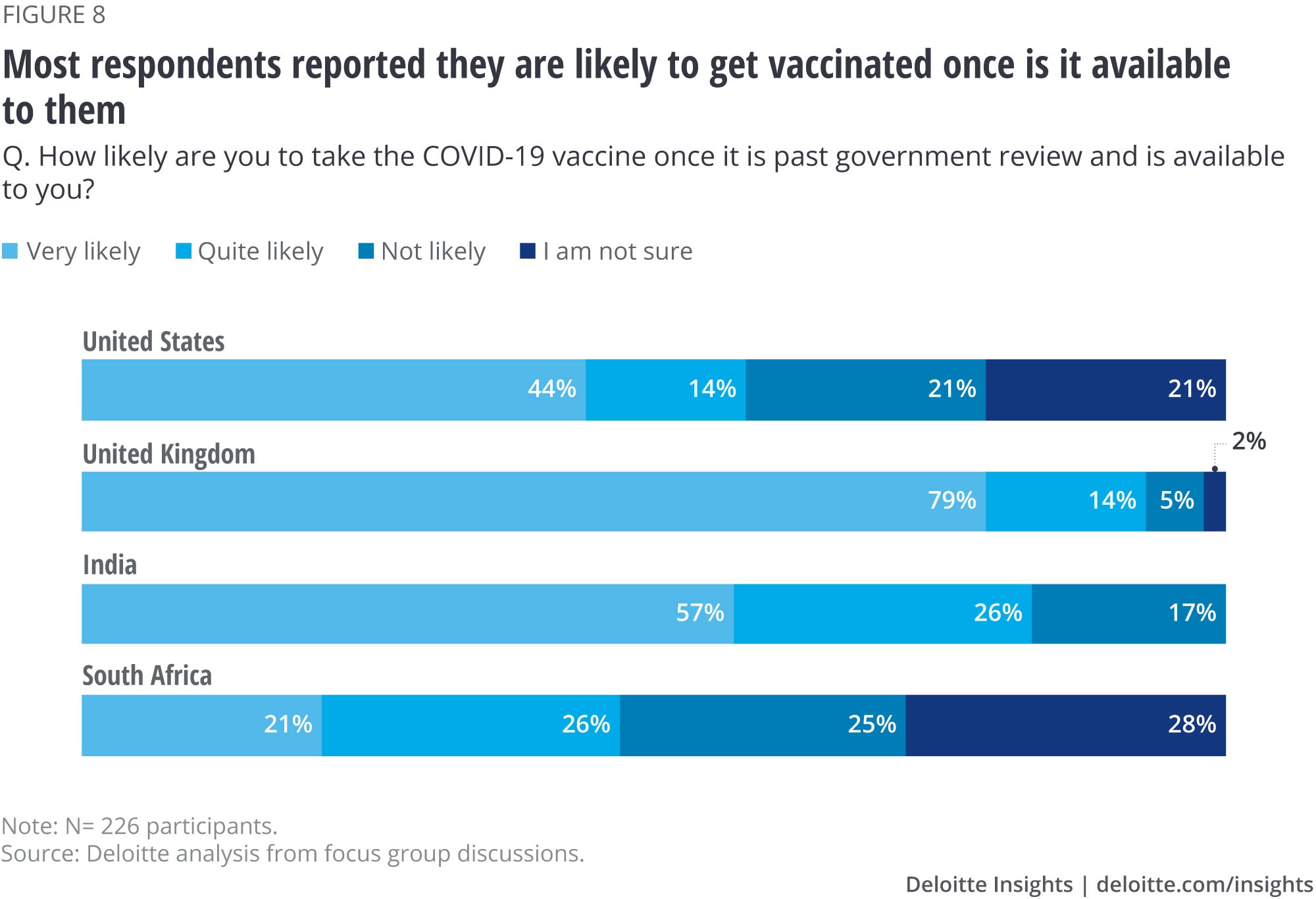

Most participants across countries are likely to take the vaccine but there is still some hesitancy

Most survey participants said they plan to get vaccinated once vaccines are approved for use by their countries’ governments and are available (figure 8). Participants said that they were motivated to protect themselves, their families, and their community, and get back to a normal life.

However, there is still some hesitancy—especially in South Africa where focus group participants are divided evenly between likely to take versus uncertain if they will take it. Analysis of qualitative responses suggest that participants are worried about the lack of information around immediate side effects and that the vaccines have not been tested long enough to understand long-term side effects. They are also not confident about efficacy and want to wait and observe the effects on other people before deciding.

Personal exposure to COVID-19 did not seem to influence the likelihood of getting vaccinated. Those who either had COVID-19 themselves or have a close relation who was infected (whether mild or serious) said they were likely to be vaccinated about as often as those who had no personal exposure at all (66% vs. 70%, respectively).

“I am unsure if I want to take it. It is new. It was made quickly. I do not feel that it was tested enough to know any long-term side effects. I would prefer to wait a little while and see how things go before making my final decision on it.”

Race/ethnicity influences vaccine hesitancy

Though our survey sample was too small to draw conclusions about how vaccine hesitancy varies by race/ethnicity, the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor from February 2021 reports that while willingness to take the vaccine once available has risen in the United States, Black and Hispanic adults continue to be more likely than white adults to say that they will “wait and see” before getting vaccinated. Half of Black adults and about one-third of Hispanic adults said they are not confident that COVID-19 vaccines were adequately tested for safety and efficacy among their racial/ethnic group and were overall less likely to report having been vaccinated already or being interested in doing so as soon as they can get it.17

The report also highlighted that having a close relationship with someone who’s been vaccinated is correlated with individuals’ own intentions to get the COVID-19 vaccine. However, Black and Hispanic adults, those with lower incomes, and those without college degrees were less likely to report that someone close to them has been vaccinated.

One way to increase trust in vaccines is to demonstrate diversity in clinical trial participation. Deloitte is working studying ways in which the industry is tackling this issue (publication forthcoming).

Strategies for improving trust

Trust matters on many levels. Increasing trust in brands, companies, and the biopharma industry can reap benefits in terms of market and political positioning. COVID-19 provides an opportunity to build on the goodwill consumers and policy makers will likely have for solutions to a pandemic that has taken a deep toll on our health and economies. Improving trust can also improve consumers’ health if they trust the medications that will help with their conditions.

“Be more transparent in the way that they develop their drugs, make it affordable and accessible, advertise better, and provide me with quality products that help with any illness that I may be dealing with.”

Pharma companies can manage and grow trust with customers by demonstrating competencein their abilities to deliver safe and efficacious vaccines and their intent to help patients in all circumstances. In our survey, some common themes emerged from consumers suggesting they question the intent of pharma companies. Consumers want more information and transparency in two areas. One is about the drug development process, how well drugs work (including any side effects), and the overall value of the drugs in managing their condition. The other theme was around drugs being too expensive (even in countries where people have low out-of-pocket costs) and companies being too profit-oriented.

“Be more transparent about how their products are made and how they operate financially. They can also engage in more welfare projects to help people afford medication.”

Companies do provide information on both clinical outcomes and financials as part of the regulatory process for drug approval and for shareholders; in the United Kingdom, this includes interpretation by doctors and pharmacists. Consumers and reporters have access to this information, but it may not be presented in a way that is easily understood. People are perhaps more interested in and knowledgeable about the clinical trial process and in the science of drug development as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Scientific experts are regularly featured on various media channels to help explain how the biology works and how to interpret clinical trial data. The major vaccine developers have also pledged not to profit from the vaccines—at least during the pandemic emergency—which may be helpful in improving consumers’ perception of the industry.

Deloitte research indicates that when a biopharma company demonstrates certain signals, consumers will view their brand more favorably. These four trust-building signals, which are consistent with how consumers defined trust in our focus groups, are:

- Humanity: Addresses the perception that biopharma genuinely cares for patients’ experience and well-being by demonstrating empathy, kindness, and fairness.

- Transparency: Indicates that biopharma companies openly share information, motives, and choices related to its decisions in plain and straightforward language.

- Capability: Reflects the belief that biopharma can create high-quality products and services and has the ability to meet expectations effectively.

- Reliability: Shows that biopharma can consistently and dependably deliver high-quality products, services, and experiences to patients.

Addressing the two major consumer concerns–transparency in drug development and pricing–can be challenging, as many people do not have the interest in truly engaging with scientific evidence or reading financial statements. But one expert noted that the pandemic might stimulate much deeper and sustained interest in the clinical trial process and new technologies such as mRNA platform therapies, and that scientific experts—including those in the mass media—can help in breaking down scientific information for consumers.

Developing a strategy—one that conveys both competence and intent—to make the industry and the companies that are in it more trustworthy should start at the top of the organization. In speaking with public relations professionals, a common theme in building trust was the tone set by the CEO in supporting a company culture that fosters it—both internally and externally. These experts pointed to several key elements of a successful communications strategy (figure 9):

- Feature leaders—especially CEOs: People connect with other people, not with companies. Strong leaders should showcase their humanity by telling stories, share their personal reasons for working in the industry, and be vocal about the value their products bring to patients. Experts said that consumers haven’t historically heard strong stories or vision, or seen much of a presence from biopharma leaders and/or scientists—unlike those from big tech companies, for example—but that trend is beginning to change, particularly as consumers pay more attention to innovation in science.

- Cultivate partnerships: The most trustworthy organizations are most likely to be able to establish relationships with other types of entities (e.g., consumer groups, foundations, academia) that in turn help improve trust in the company’s name.18 In fact, if biopharma companies partnered with technology companies to bring innovative products to market that perhaps also capitalize on the momentum of technology adoption in health care during the COVID-19 pandemic, it could be reputationally transformative for the industry. Two other key groups to consider engaging include the following:

- Physicians, nurses, and pharmacists, who are more trusted than drug companies, can help talk about products, including the COVID-19 vaccines, with patients and should be leveraged as channels for education and building trust.

- Patient advocacy groups are an important link between manufacturers and customers, particularly when it comes to understanding the patient journey and building trust around specific products and could also be important to recruitment for clinical trials.

- Build analytic capabilities: To understand the various segments with which the company interacts and what drives trust for them, and to develop measures that capture areas to improve on, biopharma companies should invest in comprehensive, advanced analytics on an ongoing basis.

- Put always-on consumer data collection systems in place. Using the latest technologies and experience management platforms can enable companies to collect data, both actively and passively, and gain insights in the moment and over time.

- Conduct consumer surveys, especially those that measure trust-building actions for humanity, transparency, reliability, and capability. These can provide data to benchmark trust in a company or a brand relative to another and over time.19 The same data could also be synced with other data to feed algorithms that spur next best actions for patients, such as reminders to fill prescriptions or to talk to their doctor about the current medication.

- Use analytics to potentially diagnose vulnerabilities at the organizational level as well. Trust levels across domains within the organization, including strategic governance, company culture, customer experience, or data integrity, could be impeding efforts to deliver products and services competently and with sincere intent, and should be identified and prioritized accordingly.

- Prioritize listening and customer experience: Companies should leverage digital technology and presence—including maintaining a patient-centric website—to engage with patients, who will be actively living with and discussing their conditions through a variety of forums. It’s worthwhile to be part of those conversations, whether through social media, apps, or other channels, and to respond to concerns and queries appropriately. Companies should also consider additional modes of engagement through digital companions to support medication adherence, track outcomes, and provide data to providers and links to other patients.

- Engage with the market consistently and continuously: Building trust is not “one and done,” nor something that can happen with a single marketing campaign. Multiple-channel campaigns that are consistent over time and have strong proof points can be ideal. Challenges in action and experience are inevitable over a company’s lifetime, and resilient and responsive organizations—ones that are open to learning from consumers—can weather these challenges. To that end, one expert pointed out that it is also important for the industry to band together—in a timely fashion—when “bad actors” in biopharma appear. This demonstrates accountability for behaviors or practices that are not representative of how the rest of the industry wants to, or plans to, operate. Historically, she said, we haven’t always seen this happen.

Perhaps most important to a discussion on consumer trust in biopharma is a recognition of the health care industry’s overall purpose—to make patients’ lives better. Unlike getting a new smartphone or a luxury vehicle, access to health care and medicines are a necessity. Patients who are seeking health care products and services—which can make the difference between life and death—are often at a low point and don’t want to feel like they are being “kicked while they are down.”20 As a result, biopharma companies are often held to an unparalleled standard when it comes to motive and profit, even though continued innovation and product availability depend on it. Building trust is a critical pathway to demonstrating the true value that biopharma companies and the rest of the health care system bring to society while also being accountable to shareholders and stakeholders.