Whole-of-state cybersecurity: Protecting the public information ecosystem

Many states are working to protect highly vulnerable entities—including local governments, schools, and public infrastructure—from increasingly fierce cyberthreats

Sam Park

John O'Leary

Alex Lewek

Sushumna Agarwal

Michael Wyatt

Small, isolated systems within states are often at the greatest risk of cyberattacks. Consider:

- In 2022, tax and motor vehicle databases in more than 45 Arkansas counties were hit by ransomware, prompting the state to disconnect automated data feeds from these county systems and causing significant disruption for motorists.1

- In 2024, the town of Muleshoe, Texas (population 5,000) had its municipal water system hacked, allegedly by state-sponsored foreign actors, prompting a manual shutdown.2

- In 2025, three hospital groups in Maine suffered a cyberattack that prompted the shutdown of all network systems and phones, causing emergency care to be provided using paper-based, manual processes.3

Public cybersecurity isn’t just about protecting data. It’s about protecting systems that deliver critical services to the public. In a highly connected world, local governments can be doorways for hackers to access larger state systems, and even privately operated systems can expose the public to significant harm.

Small, local systems may lack the resources to effectively safeguard themselves against ransomware, data theft, denial-of-service attacks, and similar cyberthreats. To protect these systems from future cyberattacks, state governments could benefit from adopting a “whole-of-state” cybersecurity approach, bringing together talent, technologies, and capabilities across jurisdictions to protect local governments and critical public infrastructure.

Why the whole-of-state ecosystem may need state support

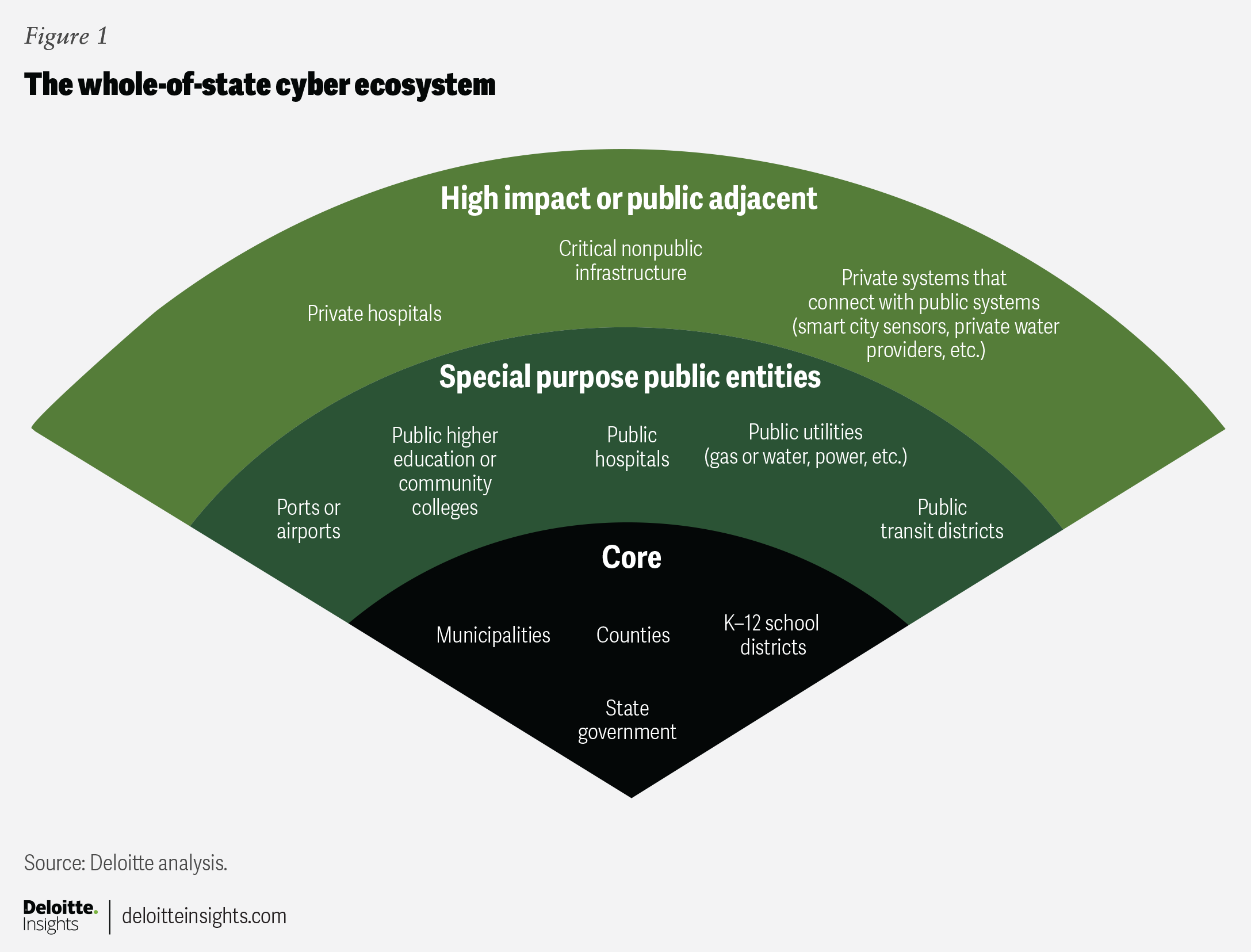

Cybercriminals, including state-sponsored foreign agents, tend to target public assets that aren’t sufficiently protected—the most vulnerable.4 These cyber-underserved entities often include local governments and K-12 school districts. Other potential targets are public colleges and universities, utilities, and critical infrastructure such as ports, airports, and dams.5 If compromised, any of these could cause widespread disruption.

There are also many quasi-public and public-adjacent institutions—private hospitals, transit systems, convention centers, port authorities—that often operate outside direct government control but are connected to public systems.

Taken together, these entities represent the whole-of-state cyber ecosystem.

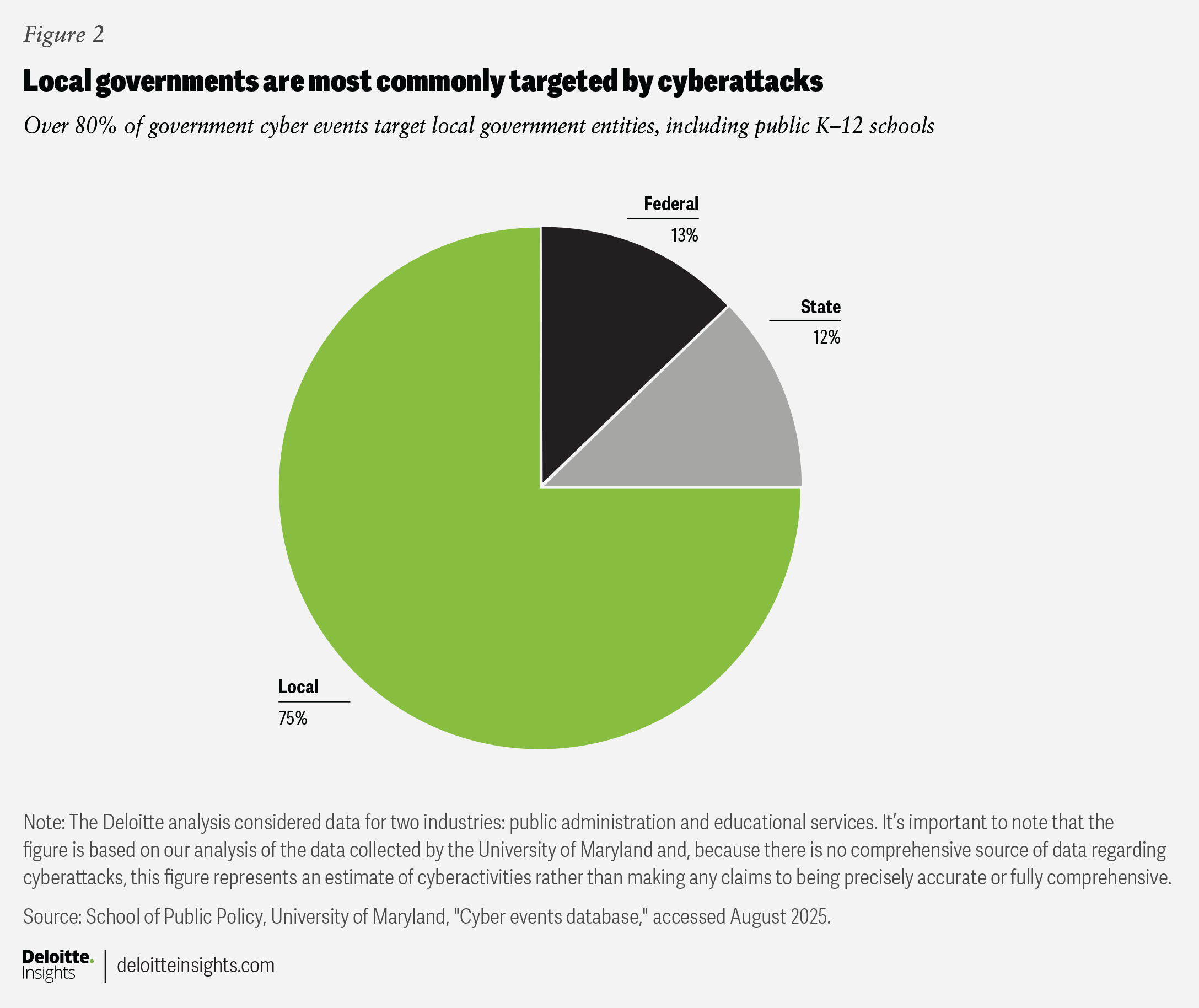

The attack surface of the whole-of-state cyber ecosystem is extensive, and the security in place is often inadequate.6 Until recently, the implicit “strategy” for cybersecurity has been highly atomized, with each entity doing what it can on its own.7 Cyberattacks are exposing shortcomings of this divided, individualistic approach (figure 2).8

National data compiled by the University of Maryland shows that local governments and K-12 public schools experience a large share of cyber events—perhaps 75% of all government attacks. The Texas Department of Information Resources estimates that in 2023, over 90% of all attacks on government in Texas targeted local government entities.9 The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s “Internet crime report,” released in April 2025, identified critical infrastructure—including government facilities, public health systems, and key manufacturing sectors—as targets of cyberthreats. The report noted a rise in both the frequency and financial toll of cybercrime, with losses totaling $16.6 billion in the past year alone.10

This evidence sends a clear signal to state policymakers: Local governments and other critical local systems are vulnerable to attacks that could put citizens at risk. In response, states are increasingly considering and, in some cases, actively pursuing whole-of-state approaches to defend against cybercriminals, hacktivists, and malicious state-sponsored foreign actors. In a highly connected world, these threats may merit more than disconnected policy frameworks and response capabilities.

Many factors can make protecting the whole-of-state ecosystem challenging:

- Lack of size and limited scale among smaller public entities

- Political independence and unclear governance

- Limited funding and decentralized cybersecurity funding streams

- Highly connected information networks (e.g., Internet of Things, smart cities, and smart grids)

- Outdated and highly vulnerable legacy systems

- Different entities (both state and local) using different technology platforms

- Non-standardized protocols and a lack of a cyber strategy for cloud, AI, and emerging tech

- Shortage of skilled cyber professionals, from frontline security operations center analysts to chief information security officers

So, what can states do to address the risk? By combining efforts, states can reduce cybersecurity costs and enable smaller entities to realize a level of collective security that would be difficult—or unaffordable—to attain individually. In many cases, from training and SOC access to insurance and efforts to defend against cyber supply chain risk, states are taking a more centralized, coordinated approach to cybersecurity.11

The journey to “whole-of-state” cybersecurity

Whole-of-state cybersecurity is not one-size-fits-all. Each state’s circumstances help determine the appropriate course of action. Many states may also be plowing new ground, as there are few established “leading practices” or mature examples of whole-of-state cybersecurity currently in place.

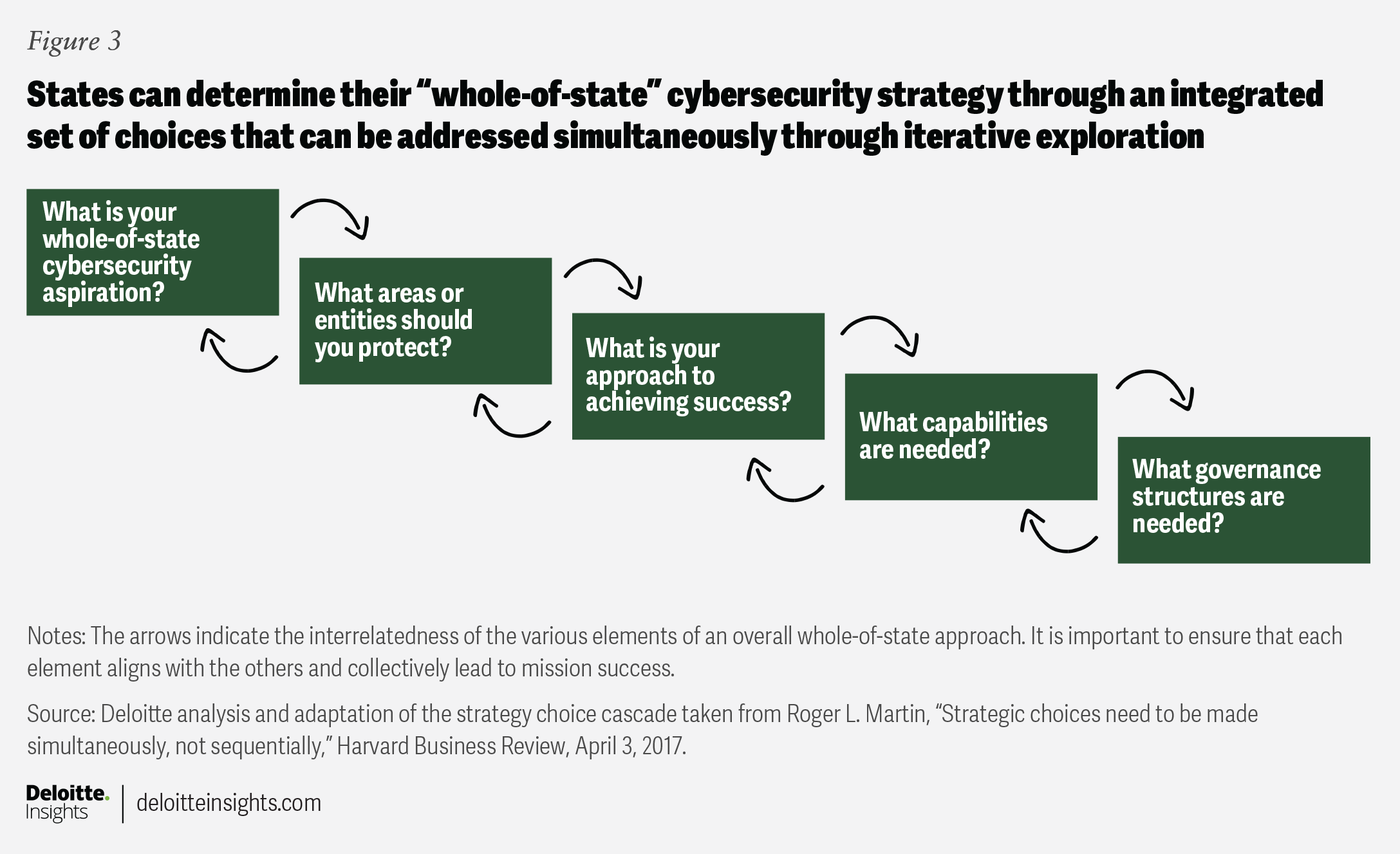

To address these challenges, the Deloitte Center for Government Insights has identified five select questions an effective strategy should answer (figure 3). These questions form a strategic choice cascade, meaning the answers should align with one another. The questions are:

- What is your whole-of-state cybersecurity aspiration?

- What areas or entities should you protect?

- What is your approach to achieving effective results?

- What capabilities are needed?

- What governance structures are needed?

What is your whole-of-state cybersecurity aspiration?

An aspiration is a future-oriented goal statement that focuses on purpose, specifically, the public benefit that will be delivered. It’s important that there be some way to evaluate—if not measure—progress toward this goal.

The aspiration could be as simple as how an informed person might describe a sought-after future state, such as: “The state provides appropriate levels of cybersecurity support—including preparation, monitoring, and incident response—not only throughout state government but also to local public entities and key functions that serve the public.”

What areas or entities should you protect?

Answering this question means deciding which domains you want to protect and which elements within them to focus on. In setting priorities, one approach is to assess both the likelihood of an attack and its potential impact. Areas with more serious potential consequences should get greater attention. For example, states might choose to support private entities that have direct health and safety implications, such as hospitals or dams. (Over 60% of dams are privately operated, but a cyberattack could trigger flooding, drinking water contamination, or other public harm.)12

Cybersecurity beyond the public sector

The federal government recognizes the compelling public interest in protecting vital systems beyond government itself. The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency has identified 16 critical infrastructure sectors, ranging from nuclear energy and health care to agriculture and finance.13

The nature of cybersecurity that plays out outside of government is complex. First, the information systems often involve many more stakeholders than just the companies operating the service, including software companies, internet and web-hosting service providers, and regulators—each with its own unique incentives. A 2022 Deloitte study notes:

“The success of security strategies such as defense in depth or layered defense depends on understanding that each of these stakeholders has a different set of incentives pushing and pulling on their behavior. Even adversaries are incentivized by different trends to increase or decrease their attacks. The challenge is that in such a complex environment as critical infrastructure, the incentives of one player may combine with the incentives of other players in unexpected ways …”14

Cyberattacks on these critical sectors can cause widespread societal harm. Just as federal officials monitor sectors of national importance, like defense, state officials must recognize that external breaches can provide entry points into interconnected public information systems and expose state and local data.

In addition, different systems may require different forms of support, depending on their criticality. The risk to the public is a product not only of how vulnerable a system may be but also of the negative impacts should that system be breached.

What is your approach to achieving effective results?

The approach to providing whole-of-state protection will depend on a state’s specific circumstances. For example, Texas, because of its large geography and broad public higher education network, chose a regional approach that partners with schools in the state’s higher education system to provide cybersecurity services to local entities. Oregon likewise leveraged its public university system (see case studies below).15

Some states may coordinate local cybersecurity services through the governor’s office. In 2022, Ohio Governor Mike DeWine issued an executive order creating a state cybersecurity strategic adviser role. The adviser coordinates cybersecurity efforts across state government and “support[s] collaboration for all state agencies, counties, and local governments, academic institutions, and critical infrastructure partners.”16 Other states may look to legislation, as Texas has, to outline the goals, roles, and funding needed to support cybersecurity across the whole-of-state ecosystem.17

These support services might be delivered directly by the state or through partnerships with academic institutions or for-profit providers. Some states may offer only a limited set of critical services while allocating funds to local governments to develop the rest, or adopt a hybrid approach.

What capabilities are needed?

Cybersecurity is not a binary concept; it encompasses various levels of maturity across multiple capability areas. It is useful to examine various cybersecurity components and consider which ones are appropriate for different local public entities. These capabilities can be organized by when they occur.

Before: Capabilities and steps that can be performed prior to a cybersecurity attack include assessments and audits of local practices; protocols for procured services (including application developers, third-party providers, and cloud providers); cyber insurance; improvements to IT infrastructure and operations for better cyber hygiene; technology governance; threat information-sharing; recruitment and development of cybersecurity talent for local entities; and training and cyber hygiene protocols for employees.

Ongoing continuous monitoring: Use of a security operations center (SOC) to provide ongoing monitoring and detection of cyberattacks. To control costs, smaller entities may rely on external providers for this capability.

During an attack: Rapid response and containment of a cyber event often involve deploying cyber professionals external to the impacted organization. This is because smaller public entities may lack the economies of scale to maintain specialized expertise. This response will often include assessing impact, protecting unaffected data, restoring impacted systems, as well as providing public information as appropriate.

After: Cyber forensics is conducted to understand what occurred and what can be done more effectively in the future.

In many cases, it would be cost-prohibitive to provide all local public entities with this entire suite of capabilities at the highest levels. But understanding all the capabilities that should be considered is important to structuring an effective whole-of-state approach.

What governance structures are needed?

Some of the most vexing questions regarding a whole-of-state cybersecurity plan are rooted in the governance structures needed to execute an aspirational vision. For agencies within state government, the largely hierarchical structure of government makes governance relatively straightforward. But the distributed nature of local public entities can make governance far more complex.

Relevant questions include: Who will provide funding? Who has the authority over which aspects of providing cybersecurity? Who is responsible for measuring progress toward goals? What is the role of state IT officials, state emergency response officials, and local public leaders? What, if any, role is envisioned for state higher education institutions? Community colleges? Private sector providers? How will different stakeholders align their interests to produce an effective, collaborative effort?

One final note: The answers to these five questions should be internally consistent. The arrows in figure 3 indicate the interrelatedness of the various elements of a whole-of-state approach. It is important to ensure that each element aligns with the others and that they collectively support mission success.

Sometimes, it can be easy to confuse activity with mission success. Different elements may be handled by different people, funded from separate budgets, or implemented at various government levels, but ultimately they should come together cohesively. The capabilities being developed should directly support an overall defensive posture, align with identified priorities, and contribute directly to meeting the stated objectives.

Case studies: How states are defending the whole-of-state ecosystem

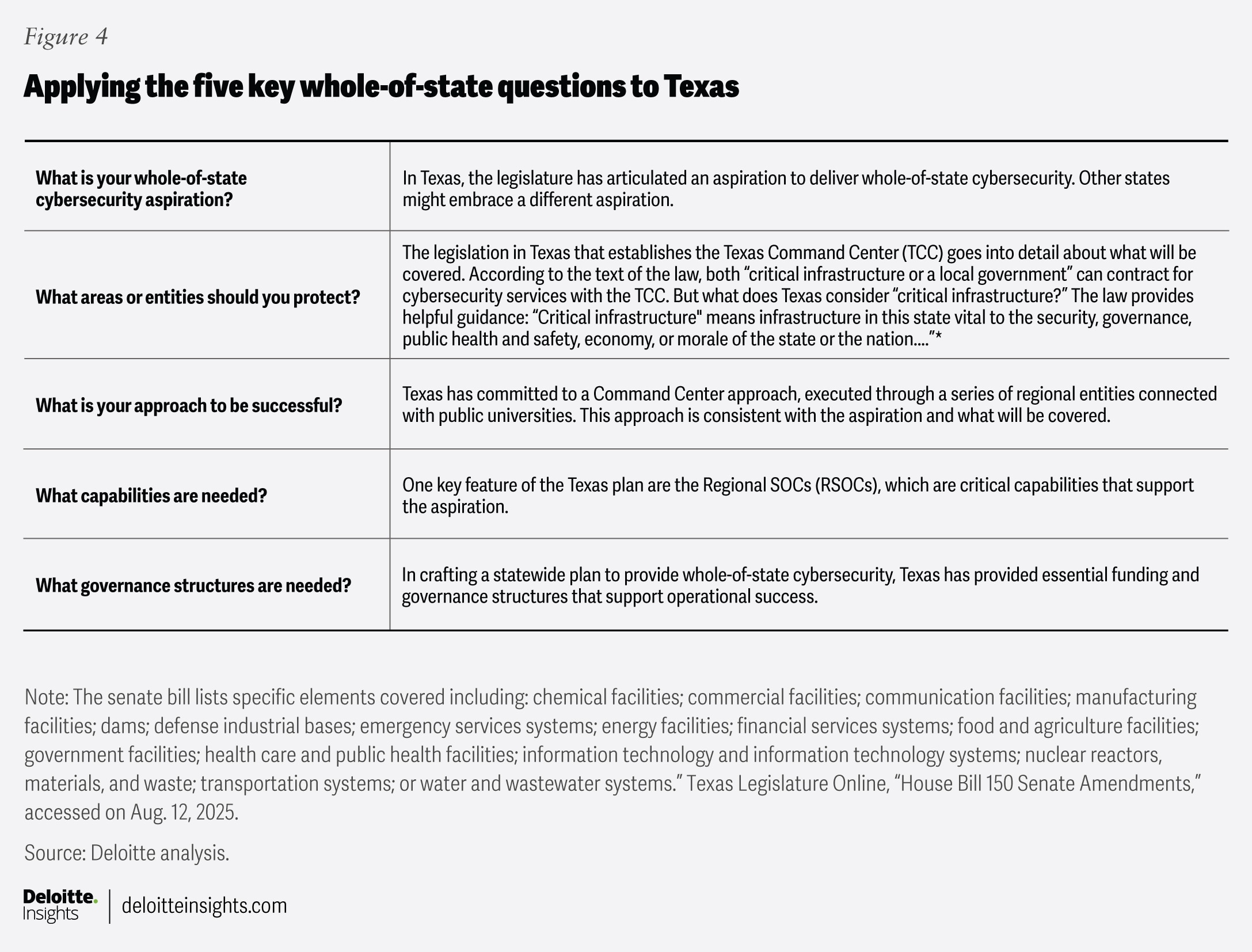

Texas: A regional support model in collaboration with public universities

Texas has significantly strengthened its cybersecurity capabilities on the path toward providing whole-of-state cyber defense. In 2021, the state enacted Senate Bill 475, which directed the Texas Department of Information Resources (DIR) to establish a framework for regional cybersecurity working groups. In 2025, House Bill 150 established the Texas Cyber Command (TCC) with an allocation of $135 million to support operations through 2027.18 The TCC will act as the state’s cybersecurity hub, encompassing sectors such as energy, water, health care, transportation, communications, and finance. It is empowered to receive cyber incident reports, conduct digital forensics, develop threat intelligence, and support workforce training.

In 2022, the DIR launched the first regional security operations center (RSOC) in partnership with Angelo State University in San Angelo, Texas. The state’s commitment to Angelo State University—both in terms of funding and expertise— is intended to enable the university to provide cybersecurity services to local governments. Housed on campus and staffed in part by students, the RSOC provides 24/7 monitoring of servers, systems, and network traffic for local governments and other public entities, identifying threats in real time.19

The RSOC also provides policy guidance, training, and support to anyone who signs up. To receive services, an entity—such as a city, county, school district, special district, state agency, public junior college, or utility—needs to contact the RSOC to inquire about eligibility. Once qualified, the entity enters into a local contract with the RSOC and can start receiving services. By involving students in hands-on cybersecurity work, RSOCs help build a pipeline of local cyber talent while also reducing staffing costs.

One strength of the RSOC model is its geographic proximity to local government entities. Although local governments aren’t required to follow state security standards, a nearby RSOC operated by a familiar university or organization can help build trust. This personal touch makes local agencies more likely to participate and accept help.20 The Texas Cyber Command prevents and responds to cyberattacks by “partnering and collaborating with state universities, Regional Security Operations Centers, federal cyber focused agencies and our local and state partners.”21

How Texas deals with the five select whole-of-state questions

Texas is seeking to build a statewide cybersecurity ecosystem that brings all entities under a strong umbrella of defense. Its approach seems to address the select questions in moving toward “whole-of-state” protection.

Other states may answer these questions differently, but a consistent set of answers is an important success factor as states grapple with this difficult challenge. Strategic choices of this kind are better made simultaneously, not independently.

Oregon: State universities delivering cybersecurity for local entities

In July 2023, Oregon Governor Tina Kotek signed House Bill 2049 into law, officially launching the Oregon Cybersecurity Center of Excellence (OCCoE) with the goal of strengthening the state’s cyber resilience while building a cybersecurity talent pipeline. Through this legislation, three state-run universities provide security monitoring operations and other cybersecurity services to local governments and other entities, while also training the next generation of cyber professionals in Oregon.22

The OCCoE is a collaborative effort among Portland State University (PSU), Oregon State University (OSU), and the University of Oregon (UO). Each university receives operational funding and supports the state’s chief information security officer across a range of cybersecurity functions, including threat information-sharing, security assessments, and security services for local governments.23

The SOC services are provided, for the time being, free of cost to eligible entities, including local governments and other public entities. The idea is to involve students in providing critical monitoring services to public entities that may lack sufficient cybersecurity capabilities. (OSU already has a functional research-SOC—ORTSOC—serving local governments and school districts, while UO is in the process of launching its own.)24 “These SOCs are teaching labs, designed like a medical school,” explains Birol Yesilada, professor and director of PSU’s Mark O. Hatfield Cybersecurity and Cyber Defense Center and founding director of the OCCoE. Just like teaching hospitals that both treat patients and train medical students, these research-SOCs serve government entities and prepare future cyber professionals in a real-world setting. “Fourth-year students monitor networks … They rotate through different tasks, learning every facet of SOC operations,” notes Yesilada.25

At PSU, the impact goes beyond students. The university offers a cybersecurity resilience certification for local governments, school districts, and special districts. In 2025, 50 people completed a program funded through a congressional earmark. “Some special districts have just two or three employees managing everything,” says Yesilada. “Our virtual program helps them build cyber resilience through simulations and tabletop exercises.”26

At Oregon State University, the SOC—formally known as ORTSOC—operates weekdays from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m., with plans to expand hours in the near future. Rakesh Bobba, associate professor at OSU and associate director of the Oregon Cybersecurity Center of Excellence, says, “ORTSOC is eager to partner with clients who believe in the workforce development mission of ORTSOC and who have at least one (part-time) IT person who can respond in case the ORTSOC detects a threat.” Bobba notes that some clients are small local governments with only a few computers, and for such entities, ORTSOC is often the primary line of defense.27

Onboarding entails ORTSOC installing a network sensor on a client’s system to collect log data—at no cost to the client. “Security assessments, network monitoring, remote incident response, and penetration testing are our core services,” Bobba adds. “We’re planning to expand that list in the coming year.”28

These are important first steps as Oregon continues its efforts to strengthen relationships among state government, the university system, and local players, laying the groundwork for future progress.

The cyber command concept: A governance approach to coordinated cyber defense

A “cyber command” approach is a mechanism for unifying the defense of multiple isolated, vulnerable entities under a single governance structure, modeled after the US military. United States Cyber Command (USCYBERCOM) was set up in 2009 to coordinate the military’s cyberspace operations. It became a stand-alone Unified Combatant Command in 2018 and provides cybersecurity services across military departments and US government agencies.29

USCYBERCOM operationalizes cybersecurity as a war front, recognizing cyberspace as an ongoing domain of conflict. Cyberspace requires an operational mindset similar to maneuver warfare since it’s an operational domain. While not a precise analogy to the challenges facing states, some aspects of the USCYBERCOM can provide useful lessons.

Like states today, USCYBERCOM began with numerous small entities undertaking their own cyber defense efforts. It instituted governance structures designed to identify the most vulnerable entry points and prioritize resources where cyber breaches could have catastrophic consequences—useful examples that states may wish to consider when structuring a whole-of-state model.30

In 2017, New York City adopted a similar proactive and centralized approach to cybersecurity with the launch of the New York City Cyber Command (NYC3).31 NYC3 coordinates the protection of city systems that provide critical services to New Yorkers. Since its inception, NYC3 has steadily expanded to offer comprehensive cybersecurity capabilities that cover every phase of a cyber incident. Its services include threat management, SOC functions, risk assessments, and in-house software development, all in pursuit of a coordinated and resilient defense against cyberthreats.32

Other efforts to promote local public cybersecurity defense

Recognizing the limitations of fragmented cybersecurity efforts, the federal government launched the State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program (SLCGP) in 2022.33 The program allocates funding to each state based on a statutory formula, with a mandate that at least 80% of the funds directly support local governments. While the SLCGP marked an important step toward a whole-of-state cybersecurity approach, its implementation has faced some challenges, funding levels have been quite limited, and the future of the program may be in doubt.34

States are also following other approaches to provide cyber services to the whole-of-state ecosystem:

- North Carolina incident response services: Facing escalating cyberthreats, North Carolina established the Joint Cybersecurity Task Force, an alliance of state, local, and federal entities. The task force provides support to government entities statewide, including schools and local agencies, delivering services such as incident coordination, technical aid, and on-site recovery. The task force includes the North Carolina Department of Information Technology, North Carolina Emergency Management, the National Guard, the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security, and local IT volunteers.35

- North Dakota: Since 2020, North Dakota has launched several initiatives to deliver whole-of-state cybersecurity services, including the establishment of a central SOC to monitor and protect over 250,000 devices across state and local entities. Using AI-driven threat detection, daily security alerts declined by 99.6%.36 The state also deployed advanced endpoint protection—free of cost—to schools and local governments, helping to secure thousands of devices.37

- New York shared services program: New York State launched the Shared Services Program in 2022, offering advanced cybersecurity tools to county and local governments regardless of their technological maturity. The program’s flagship service is an endpoint detection and response solution that monitors devices for suspicious activity. Crucially, data from these tools feeds directly into the New York State SOC, giving the state a comprehensive view of cyberthreats across all levels of government.38

Fighting the battle of Muleshoe

Why would foreign hackers bother disrupting a water system in a small town like Muleshoe, Texas? Perhaps they’re practicing—testing defenses, probing weaknesses, and preparing for larger-scale disruptions.

Cybersecurity is a persistent battleground, with cyberattacks growing in scale, frequency, and impact. Even the smallest local entity could be on the front line of an ongoing global cyber conflict. As the federal role in cybersecurity support shifts, the responsibility to protect systems is increasingly falling on state and local governments.

State leaders can help build a resilient and coordinated defense. By addressing the five questions highlighted in this article, leaders can help craft a vision for whole-of-state cybersecurity and a clear pathway to achieving it.

As part of building a whole-of-state vision, leaders should also consider the following:

- Working with the legislature to enhance understanding of the risks associated with insufficient cybersecurity preparedness across the whole-of-state ecosystem

- Building relationships with local officials to address incident prevention, monitoring and response, and to understand their concerns

- Building relationships with higher education leaders and workforce development leaders throughout the state to strengthen the cybersecurity talent pipeline

- Collaborating with federal officials at CISA and other federal agencies to understand and minimize gaps in cybersecurity

While many states have taken initial steps, few have fully addressed the five select questions outlined in this article.39 Answering them—collectively and strategically—will be essential on the journey toward building resilient, statewide cybersecurity postures. Each state’s path will differ, and the precise structure of a coordinated defense posture will inevitably vary. But the reality of a growing threat to the whole-of-state ecosystem is driving many states toward delivering stronger cyber defenses for smaller, more vulnerable public entities.