Refit to rebuild: A blueprint to help boost US commercial shipbuilding competitiveness

Shipbuilding competitiveness can be strengthened by catalyzing investable demand in ship autonomy, alternative fuels, and smart ports—the future of the maritime value chain

Adam Routh

Pete Heron

RADM John W. Mauger

W. Robert de Jongh

Nick Pant

Akash Keyal

The picture is hard to ignore: In 2024, US commercial shipbuilding represented just 0.1% of global shipbuilding output.1 That same year, China State Shipbuilding Corporation—the country’s largest shipbuilder—delivered more commercial tonnage than all US yards combined since the end of World War II.2 The United States ranks 22nd among global flag registries and only transports 0.2% of global container traffic, despite 6% of that traffic being processed by US ports (see “How did US shipbuilding get here?”).3 There is also significant foreign ownership of US port infrastructure.4 By comparison, China accounts for 53%, South Korea for 29%, and Japan for 13% of the global commercial shipbuilding market share, with the rest of the world making up the remaining 4%.5

The United States recognizes that a commercially competitive shipbuilding industry would help preserve and enhance both economic and national security.6 To achieve this, US shipyards and their suppliers would need to profitably design, build, and service commercial ships that can match or outperform global rivals on total cost, speed, quality, safety, and life cycle support.

Beyond boosting trade, a vibrant commercial shipbuilding industry can help underwrite naval capacity by keeping yards, suppliers, and talent engaged between periods of naval demand, making the maritime industrial base more sustainable and innovative. When private demand drives modernization, public funding can be catalytic rather than permanent.

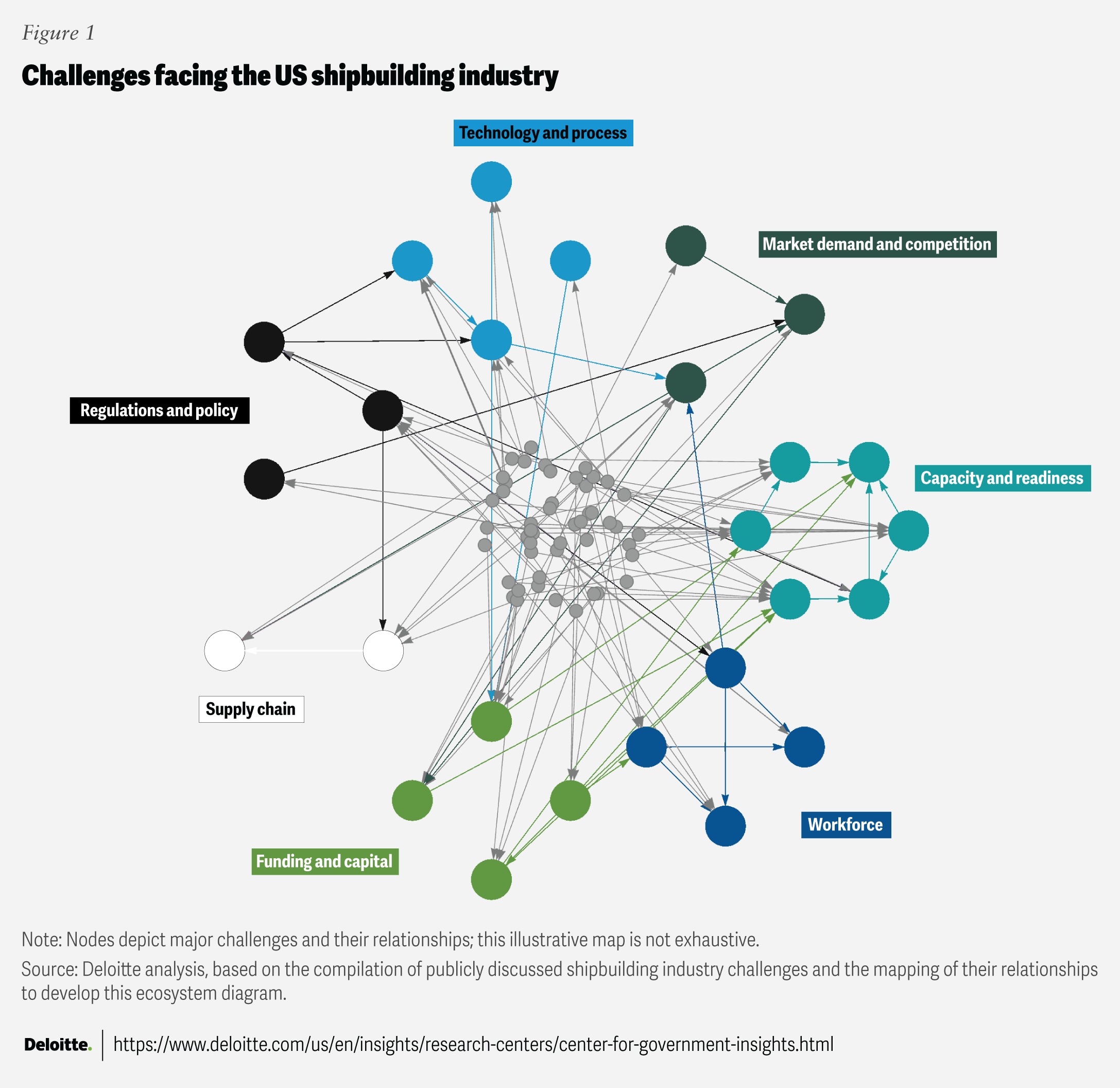

However, the US shipbuilding industry faces a range of interconnected challenges—including complex regulations, funding shortfalls, and gaps in workforce and technology (figure 1)—that often result in slow, costly production and overdependence on naval contracts.7

Copying the subsidy-heavy models used by global shipbuilding leaders is not a viable path for the United States, as it lacks state-owned shipbuilders, suppliers, and large conglomerates that can absorb industry losses when they occur. This means that while subsidies can keep US shipyards operating in the short term, they do little to build long-term competitiveness.

The United States should pursue emerging opportunities in autonomous shipping, alternative fuels, and smart ports—disruptive segments reshaping the shipping industry. These new markets can generate investable demand across the maritime value chain, delivering near-term revenue while laying the groundwork for higher‑complexity builds. This is because these emerging markets rely on cross-industry technologies—many of which the United States already leads in—such as artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, cloud, and energy solutions. This can help raise more domestic and foreign capital, attract more firms with additive workforce skills and experiences, and scale demand for new US maritime products faster than those already controlled by traditional shipbuilding leaders.

These new markets can generate investable demand across the maritime value chain, delivering near-term revenue while laying the groundwork for higher‑complexity builds.

Recommendations for getting started:

- Using public funds to unlock private sector investment and make capital flows more dependable.

- Creating maritime markets that generate demand for new US-built ships and give investors confidence in returns.

- Building with allies and close partners to strengthen and secure supply chains while attracting more foreign investment.

How did US shipbuilding get here?

When steam and steel replaced wood and sail in the mid-1800s, US shipyards—which were strong in wood construction—transitioned more slowly than their British competitors. By the 1890s, the United States played only a limited role in global commercial shipbuilding markets.

The Jones Act sustained a protected US domestic trade, and mobilizations during World War I and World War II showed that the United States could scale up quickly, though at higher costs and only for limited periods.8

After the wars, capacity shrank as Japan, then South Korea, and China expanded and modernized. An effort in the 1970s to rebuild US commercial shipbuilding faded after the oil shock and subsequent subsidy changes. Naval demand helped offset limited commercial demand, but budget volatility led to inconsistent order cycles.

Over time, structural factors—higher input costs, a smaller, protected market that limited scale and learning, and policies focused more on stability than productivity—have kept US commercial ships comparatively expensive and output low, constraining competitiveness against leading Asian producers.9

What’s holding back US shipbuilding

Issues affecting US shipbuilding span the entire maritime value chain. The industry is constrained by a complex web of interdependent challenges—including supply chains, shipyard capacity, limited workforce, financing, and demand—where weakness in any node can affect others (figure 1).

When traditional government programs focus on stimulating just one node—such as buying ships—they may create temporary increases in volume but rarely generate the lasting price signals or risk-return profiles needed to unlock private investment across the value chain: upstream (steel and refining), midstream (shipyard modernization and workforce development), and downstream (port and logistics upgrades).

These structural inefficiencies shape a predictable outcome: US ships often have longer build times, significantly higher unit costs (sometimes up to four times higher),10 and a reliance on defense demand that leaves commercial programs under-scaled and less competitive than foreign builds.11 These limitations are further compounded by global maritime industry dynamics that rely on significant subsidies (see “Asia’s shipbuilders leverage state support and private sector conglomerates to outpace global competition”).

Subsidies have been important to US shipbuilding, but the United States can’t easily mirror the models of industry leaders that use state ownership or conglomerates to absorb recurring losses and lock in market share. US shipyards are mostly privately owned, and maritime industrial policy tends to be fragmented. In addition, appropriations, procurement, and antitrust processes and rules can limit open-ended, value chain-wide support akin to large foreign maritime industry subsidies.12

Subsidies have been important to US shipbuilding, but the United States can’t easily mirror the models of industry leaders that use state ownership or conglomerates to absorb recurring losses and lock in market share.

Therefore, the United States will likely need to pair targeted, near-term subsidies that keep shipyards, suppliers, workers, and ports stable with steps that build new commercial markets and attract private capital. It may be most effective to implement a phased transition: sustain today’s ecosystem while new markets scale, take on more risk, create new demand for US ships and maritime products, and eventually reduce reliance on subsidies. Government demand for naval and other missions will likely continue, but the industry’s center of gravity should shift toward durable, diversified commercial markets, transforming temporary government support into lasting competitiveness.

With these factors in mind, to shape the next phase of shipbuilding, the United States should focus on emerging market segments—where the rules are still being set and where its comparative advantages can have the greatest impact.

Asia’s shipbuilders leverage state support and private sector conglomerates to outpace global competition

Globally, the shipbuilding industry relies on significant government subsidies, with many of the largest firms either government-owned or often operating at a loss.13

While subsidies are common, China’s subsidization is unique given its scale across the maritime value chain.14 Beyond ship construction, China subsidizes key shipbuilding inputs such as steel, invests in port and broader transportation infrastructure (both domestic and foreign), provides financial and other benefits to encourage exports, and maintains lower workforce compensation requirements than other leading shipbuilders.15 These factors enable China to produce ships quickly and at lower costs than its competitors.16

Indeed, roughly 70% of commercial ships produced in Chinese shipyards in recent years have been ordered by foreign firms.17 Globally, China dominates large cargo vessel sales, produces over 70% of ship-to-shore cranes, 86% of intermodal chassis, and 95% of shipping containers, and has an increasing share of other maritime trade components and products.18 China also holds a considerable market share of other important shipbuilding inputs, such as steel.19

China’s subsidies to state-owned enterprises are key to its ability to gain market share. Through these enterprises, China is able to absorb industry losses through indirect returns on investment.20 For example, by one estimate, for every dollar China provided in shipbuilding subsidies (US$91 billion between 2006 and 2013), it netted only 18 cents in direct return.21 Yet the same analysis found that China’s investments in shipping likely played a major role in the nearly 5% (US$144 billion) increase in the country’s annual trade volume.22 Strategies to absorb shipbuilding losses aren’t unique to China. In South Korea and Japan, large private sector conglomerates have the capacity to manage losses through subsidies and alternative sources of revenue.23

Maritime autonomy, alternative fuels, and smart ports can disrupt global markets and help power America’s maritime resurgence

Revitalizing US shipbuilding requires an actionable strategy that delivers near-term gains in competitiveness despite domestic and global market challenges. It also means creating opportunities across the maritime value chain, because in established segments, rivals can quickly ramp up subsidies to offset US gains from single-market strategies.

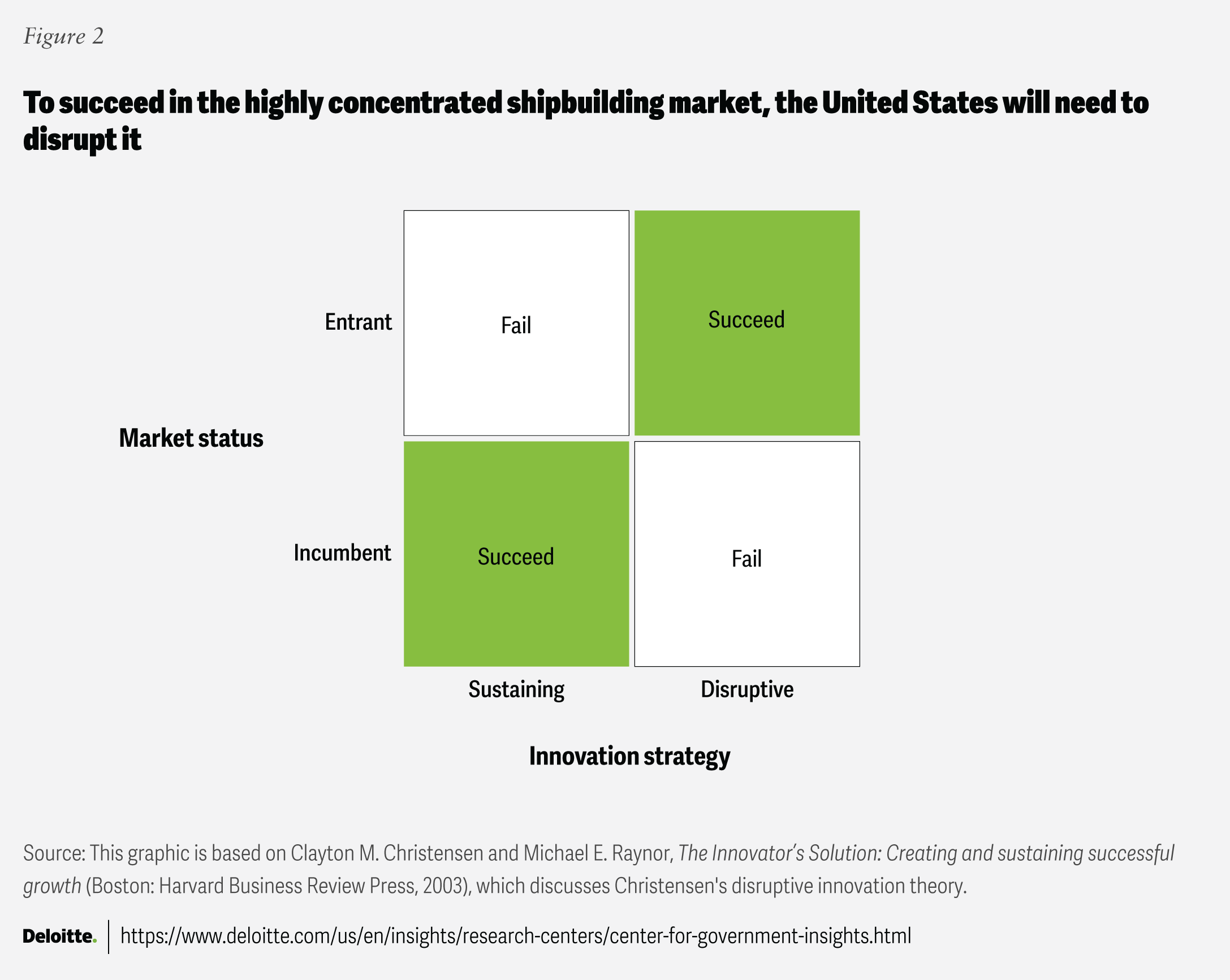

Digitization and advanced transportation technologies are major trends helping to shape the future of transportation, enabling innovation, increased efficiency, and greater sustainability.24 In particular, autonomous shipping, smart ports, and alternative fuels represent significant emerging market opportunities expected to define the future of shipping. According to disruptive innovation theory (figure 2), if developed at scale, these new markets can enable the United States to reset the basis of competition and shift demand toward US-made ships and maritime systems.25

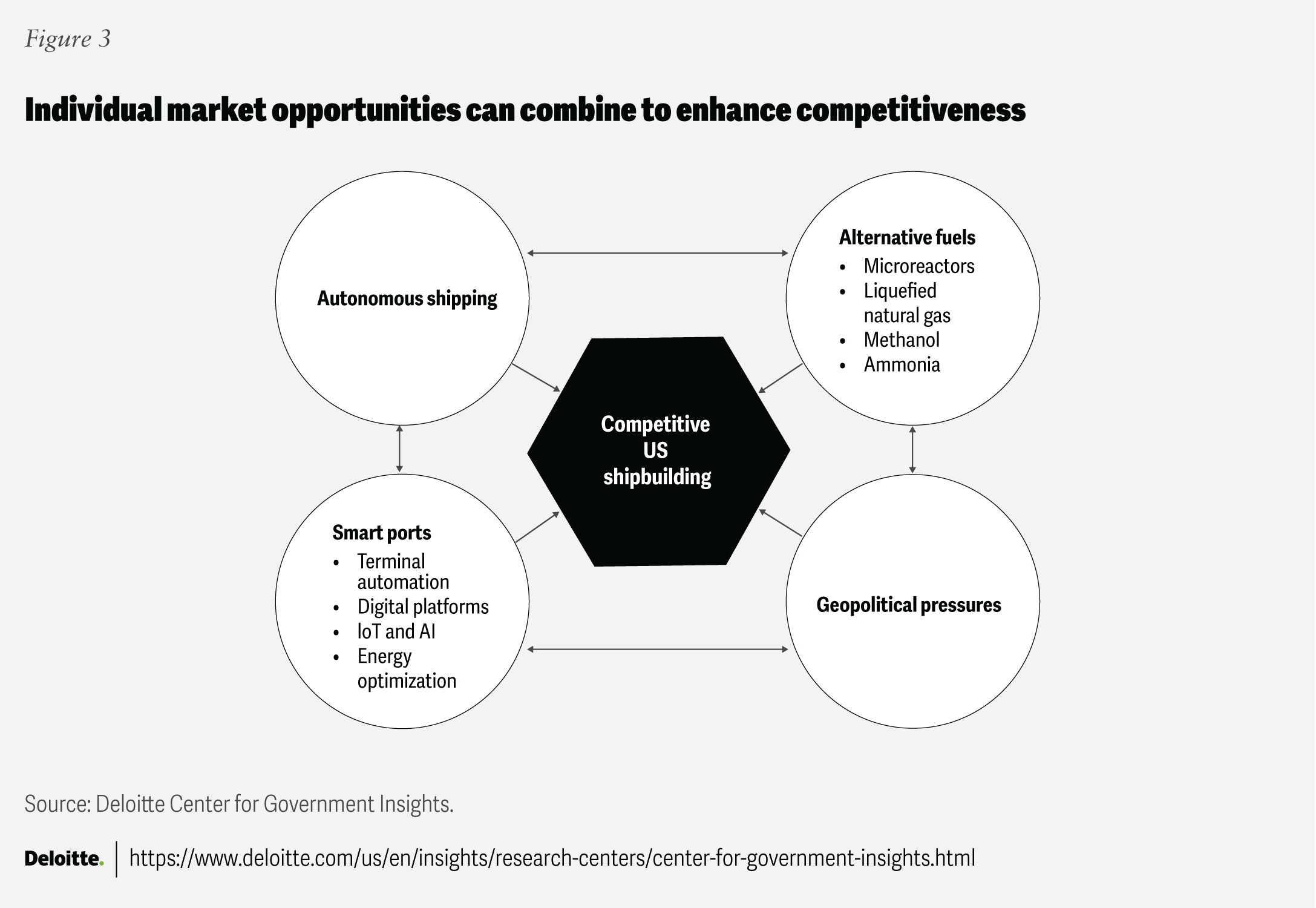

These market disruptors aren’t separate bets; they form an integrated strategy that can improve the economics of US maritime markets (figure 3).

Autonomy: In the near term, autonomy can drive demand for newbuilds and refits of small- to medium-sized coastal vessels—where US demand is strongest26—while validating the technology for larger ocean-going ships.

Alternative fuels: The shift to alternative fuels changes the hardware mix—engines, fuel systems, safety features—creating market space for US component suppliers.

Smart ports: By supplying enabling infrastructure—such as alternative-fuel bunkering and port systems optimized for autonomous ships—smart ports can facilitate trade and help stimulate demand for new ship types.27

Put simply, this integrated strategy can create net-new industry demand across the US maritime value chain, leading to greater investment (both foreign and domestic), increased demand for new US ships, and more jobs.

To build new market segments without relying on significant long-term subsidies, the United States should lean into its comparative advantages—its sophisticated business environment, deep capital markets, and impressive research and development capabilities (see “Private capital, not subsidies, can be the US edge in next-gen shipping”). Each of the three disruptive emerging industry segments maps directly onto those strengths: they rely on cross-industry capabilities—software, sensors, power systems, and data platforms—where the United States already leads. This alignment can draw in more American firms, investors, and research labs, speeding innovation and modernization (like smart manufacturing) across the US maritime industrial base.

To build new market segments without relying on significant long-term subsidies, the United States should lean into its comparative advantages—its sophisticated business environment, deep capital markets, and impressive research and development capabilities.

Private capital, not subsidies, can be the US edge in next-gen shipping

According to the 2024 World Intellectual Property Organization’s global innovation index, the United States ranks third among the world’s top innovation economies, just behind Switzerland and Sweden.28 With its deep commercial markets, strong research and development capabilities, and robust capital networks, the United States is uniquely positioned to leverage more private investment—rather than rely on subsidies—to accelerate the development and scaling of autonomous ships, alternative fuels, and smart port technologies in an effort to outpace global competitors.

Market and business sophistication

The United States offers an unrivaled ability to raise and deploy more diverse private-sector capital, positioning it to make the bold investments needed to fund a more competitive maritime industry. As a global leader in market sophistication, the United States excels in credit, investment, trade, diversification, and market scale.29 It also ranks second globally in business sophistication, with strengths in knowledge workers, innovation linkages, knowledge absorption, and global brand value.30

Illustrative examples:

In 2024, US funds accounted for $209 billion, or 57% of global venture capital activity, driven by AI mega-rounds and late-stage investments, supported by networks of angel investors, corporate venture capital, and hedge funds.31

- More than 52% of all US jobs are in knowledge-based roles.32

- Strong links among universities, federal labs, and private industry support a deep knowledge workforce, enabling the rapid movement of ideas from research to commercial application.33

- The United States uniquely combines extensive market liquidity with a large, high-income consumer base. This scale can shorten payback periods and support larger product investments.34

Leading in R&D

The United States has unmatched R&D efficiency and scale, priming it to develop the next generation of shipping innovations. It is a global leader in corporate R&D spending, university rankings, the impact of scientific publications (H-index), gross expenditure on R&D as a percentage of the gross domestic product, research talent, intellectual property royalty receipts as a percentage of total trade, and overall software spending.35

Illustrative examples:

- US business R&D alone equals about 2.8% of GDP—the third-highest share among advanced economies and, in absolute dollars, by far the largest.36

- The United States ranks first globally in H-index citations, indicating that its papers and patents are the most referenced in global literature.37

- US “unicorn” valuations equal 7.6% of GDP—the world’s highest ratio—driven by AI and biotech mega-deals.38

- The United States ranks first in software spending, driving the highest intangible asset intensity.39

- Twenty US metropolitan areas—from Silicon Valley and Seattle to Boston-Cambridge and Austin—are listed among the World Intellectual Property Organization’s top 100 science and technology clusters worldwide.40

Combined, these strengths make the United States a global innovation engine and provide an ideal path to advanced maritime and shipping technologies.

Autonomous shipping is key to the future of shipbuilding

Globally, autonomous shipping is a leading innovation priority for the maritime industry. These ships aim to lower costs, enhance safety, boost fuel efficiency, and address mariner labor shortages—benefits that can help increase global trade. This new class of ships can also leverage new manufacturing approaches, like smart manufacturing (see “The role of smart manufacturing in US shipbuilding”).41 Despite wide interest, autonomous shipping remains in its early stages, with development expected to progress beyond prototypes and achieve limited commercial deployment by 2030.42

The role of smart manufacturing in US shipbuilding

What it is: Smart manufacturing in shipbuilding refers to the use of data-driven, connected, and automated production methods. This includes digital design‑to‑fabrication, modular construction, advanced welding and robotics, additive manufacturing, and in-line quality control. These technologies can help reduce costs, shorten cycle times, and minimize defects in building and servicing commercial vessels.

What it means: Standardized designs and modules, interoperable data from engineering through suppliers and yards, an upskilled workforce, and targeted capital upgrades can raise throughput and first‑pass yield, enabling US shipyards to compete profitably.

How it can help US shipbuilding competitiveness: Smart manufacturing can accelerate retrofits and newbuilds (including autonomous and alternative‑fuel ships), improve total cost and schedule reliability, broaden the supplier base by tapping strengths from other industries, and strengthen the industrial base on which defense also relies.43

How autonomous shipping plays to America’s comparative advantages

Why now: When it comes to developing the technology needed to realize autonomous shipping, America’s strengths in R&D and market and business sophistication provide a clear competitive edge. The United States leads the world in AI development, including research, economic activity, infrastructure, and machine learning models, among other areas.44 Nearly half of global private sector AI investments originate in the United States, and in generative AI specifically, US investments exceed those of the next several leading countries combined.45 In 2024, nearly half of all US venture funding went to AI startups.46

Autonomous shipping isn’t new to the United States. In 2018, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s Sea Hunter sailed more than 5,000 miles between San Diego and Hawaii without anyone on board.47 Building on this foundation, in recent years, new US companies have raised hundreds of millions of dollars to develop autonomous naval ships, driven in part by the US Navy’s increasing orders for large uncrewed surface and subsurface vessels.48 Further supporting this growth, the recently enacted tax bill, commonly known as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, allocated several billion dollars for the development of autonomous and unmanned ships.49

Autonomy’s path around existing industry challenges: The United States does not need to immediately expand shipbuilding capacity to enter the autonomous market, since early demand will likely focus on coastal vessels like barges and tugs—types of ships that already align with US shipbuilding strengths.50

Developing the brains of autonomous ships—software, sensors, and systems—separately from the physical construction of the ships can create additional exportable products and new opportunities with trading partners. Similarly, while funding for US shipbuilding innovation often stalls due to weak demand for US-built ships,51 autonomous shipping can be different, considering its technologies are increasingly relevant in defense and civil maritime applications and permit new software-style economics,52enabling access to broader pools of venture and strategic capital than established shipbuilding segments.53 Autonomy’s evolution can mean more demand for small yards, a workforce that expands from shipping to AI, sensors, and more, and foreign direct investment from trading partners eager to adopt leading American technology and standards.

Autonomous ship adoption faces hurdles but presents opportunities: Building trust in autonomous ships will be important for addressing potential regulatory concerns, securing insurance, gaining workforce support, and attracting customers.54 However, these challenges could also present opportunities for the United States. America’s regulatory environment enables the safe and rapid development of standards and policies that other countries can trust.

Alternative fuels can generate new demand for ships and US energy

Alternative fuels for ships—such as liquefied natural gas (LNG), methanol, biofuels, ammonia, hydrogen, battery-electric power, and microreactors—are helping transform the shipping industry. The growing demand for these fuels is driven by their expected cost-competitiveness benefits, the desire to reduce vulnerabilities from constrained fuel supply chains, and various global emission regulations.55

In 2024, global shipowners ordered 600 vessels powered by alternative fuels, 50% more than the previous year.56 Although these new ships account for about 5% of the global fleet, alternative-fuel ships are a fast-growing segment. Despite a broader slowdown in new builds in 2025, orders for alternative-fuel ships continued to grow in the first half of 2025 compared with the same period in 2024.57

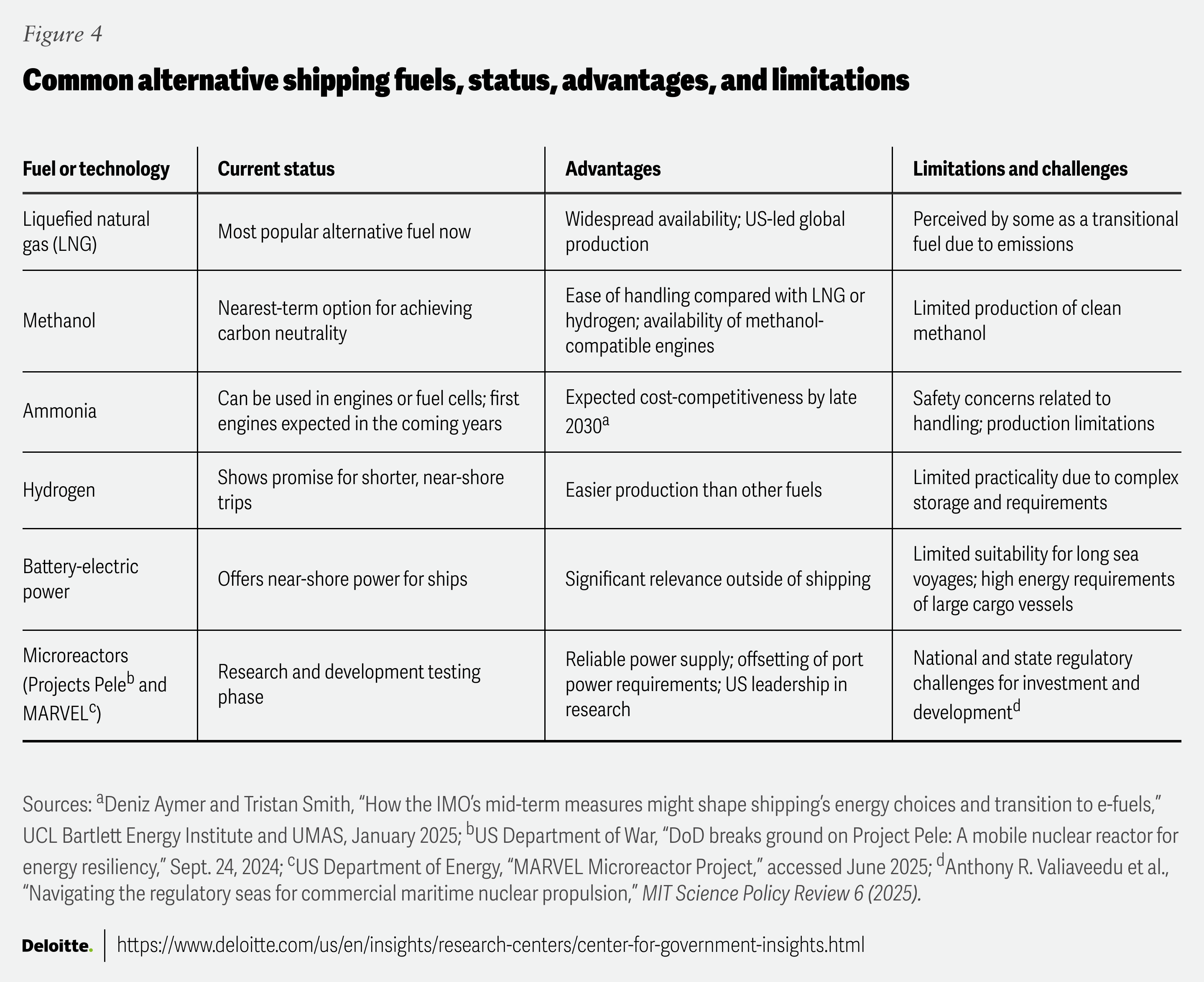

Alternative shipping fuels vary widely in maturity and application (figure 4), though many also have applications beyond shipping. Rather than investing in every option, the United States should make targeted bets on the most promising fuels—as well as the supporting port power systems, engines, and infrastructure—to stimulate more free-market competition and deliver quick wins for US shipbuilding competitiveness. Importantly, developing alternative fuels doesn’t have to come at the expense of US oil markets. Shipping accounts for only 5% of global oil consumption.58 So, even substantial efficiency gains or fuel switching in shipping are likely to have a limited effect on overall crude demand.

How alternative fuels play to America’s comparative advantages

Why now: The United States is a global energy leader and the world’s largest LNG exporter, giving it a near-term lever to shape maritime fuel markets.59 Nuclear energy also aligns with surging demand for resilient power (such as data centers) and national security needs (energy independence and remote installations).60 That’s why private sector investment in nuclear energy is rising, with total deal value in 2024 alone surpassing that of the last 15 years combined.61

Global demand for alternative fuels is already creating opportunities for US shipyards.62 Developing these markets can further drive retrofit projects, expand production of US-made fuel systems and components, and attract trade deals and foreign investment within years rather than decades.

Alternative fuels’ path around existing industry challenges: Because alternative fuels are used beyond shipping, private capital and R&D won’t be limited to what shipbuilders or limited government subsidies can support. For instance, rather than having to address limited shipyard capacity first, the United States can pair LNG export deals and overseas LNG infrastructure investments with programs that grow US maritime LNG equipment, engines, and safety systems—ideally in partnership with leading builders like South Korea. The United States can also leverage its relationships with Trinidad and Tobago to accelerate ammonia innovation, matching the world’s top exporter with the world’s top importer to seed pilot projects and establish standards.63 Maritime nuclear energy offers a step change: faster vessels, infrequent refueling, and the ability to provide shore power—creating new revenue streams and operational gains for ports.64

Alternative fuel adoption faces hurdles but presents opportunities: Other shipbuilding nations are also investing in next-generation fuels, and their infrastructure, safety, and regulatory matters will require time and resources to address. Reducing the cost of alternative fuels so that they are price-competitive with oil will also need to be addressed. Even so, the United States’ strengths in energy tech, finance, and standards—combined with cross-industry demand for US energy—position it to set the pace and capture outsized value as these markets scale.

Linking new ships with new trade via smart ports

Demand for new ship types often depends on port infrastructure that enables and encourages their use. Thus, increasing demand for US-built ships will be more difficult without modernizing US ports.

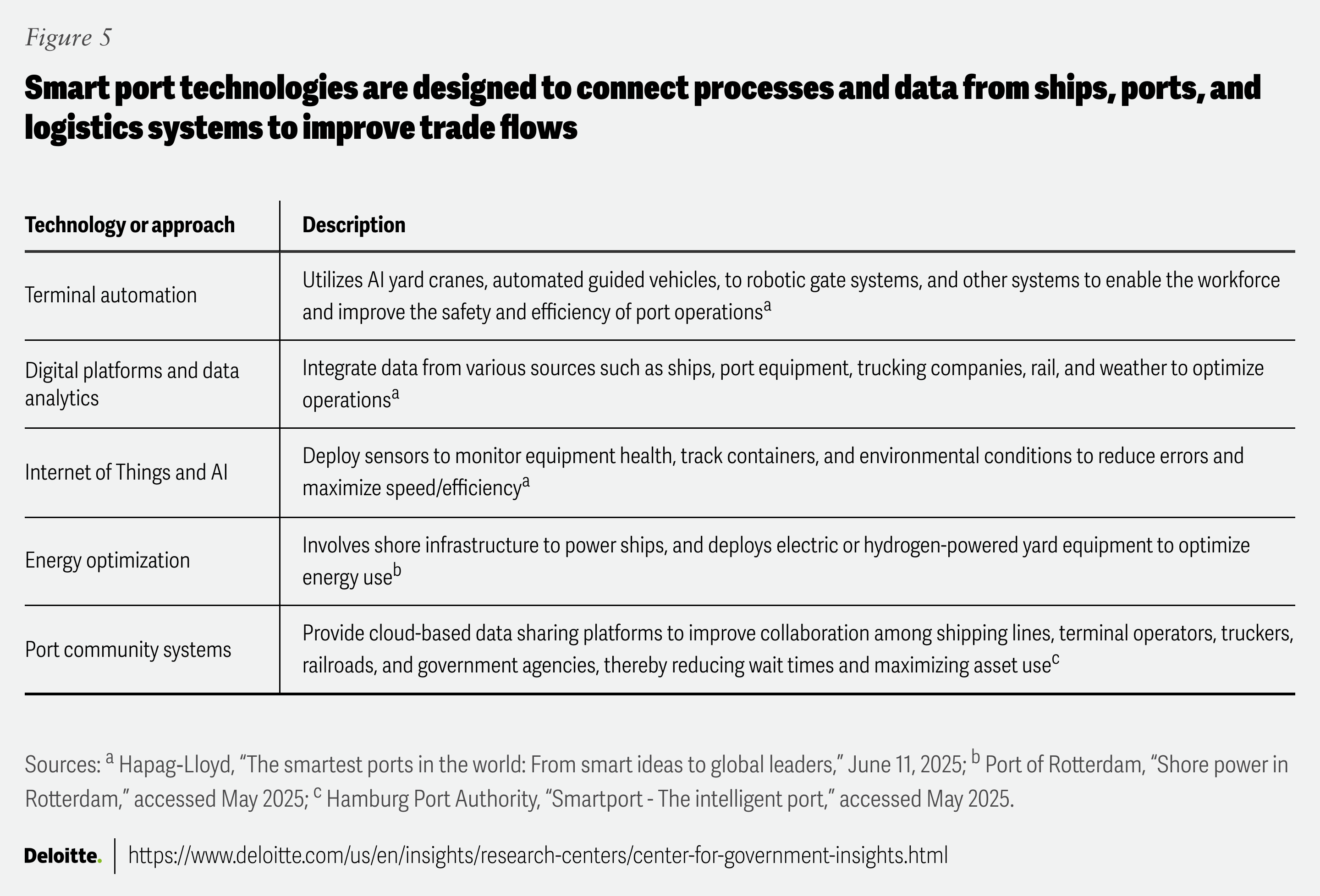

Smart ports leverage advanced technologies, such as automation, data analytics, and IoT solutions (figure 5) to improve port performance and create operational efficiencies. These improvements can help enhance trade flows and resiliency, increase investment in production and distribution systems, support manufacturing and logistics growth, expand employment opportunities, and raise income levels.65 More efficient, service-focused ports can also increase the pull of policies, like port-preference incentives and related efforts, encouraging more US and US-bound cargo to be shipped on US-built vessels.66 Conversely, less efficient ports can cause shipment delays, supply chain disruptions, and higher import and export costs, reducing trade competitiveness.67

Interest in port optimization is increasing globally, leading to disparities in port performance rankings. For example, according to the World Bank’s 2023 container port performance index, China is home to 13 of the world’s top 50 best-performing container ports, including Yangshan—the number one performing port.68 Meanwhile, the top-ranking US port, Charleston, is ranked 53rd.69 A key factor that sets the top-performing ports apart is the level of their digital connectivity and automation.

Large US ports, such as the Port of Los Angeles, have adopted some tools, like digital twins, to create important efficiencies. However, not all US ports have adopted the technologies necessary to optimize port operations. Even among those that have, differences in data standards and the tools themselves can limit how effectively ports can share logistics information, leading to inefficiencies that can add time and cost.70

How smart ports play to America’s comparative advantages

Why now: The United States is a global leader in many smart port technology areas across R&D, investment, and commercialization, and the overlap with broader Industry 4.0 trends enables it to apply existing expertise directly to port modernization, creating new jobs, attracting investment, and generating port demand in the process.71 As many countries diversify strategic industries, like shipping and related supply chains, new demand is emerging for trusted, smart port technologies.72

Smart ports’ path around existing industry challenges: Smart ports draw on cross-industry digital technologies like automation, digital twins, IoT, and data platforms that are being built and scaled well beyond shipping. America’s strong trade networks and alliances, combined with trust in American businesses and technology, offer opportunities to export US smart port solutions.

Deploying these solutions internationally would not only expand market share for American products but also help establish US standards within global shipping operations, further strengthening US influence in global trade. The benefits of investing in port optimizations also extend beyond the shore. By improving efficiency, ports can attract a broader mix of private capital for other transportation innovations, like autonomous trucking and smart warehouses, which would be needed to support higher trade volumes.73

Smart port adoption faces challenges but presents opportunities: Standardizing US port systems and solutions is no small task, given the differences in port ownership and demands, among other factors. The market is beginning to take shape, with early leaders emerging in countries such as China and the Netherlands. However, smart ports are still the exception worldwide—a scarcity that leaves substantial room for US entrants to compete with differentiated technologies and scale solutions globally.

A strategic plan to compete differently

One way for the United States to build more ships and maritime products is to develop the markets that will buy them. New, US-led markets in the disruptive segments discussed above can activate the full maritime value chain—and, crucially, adjacent sectors where US firms already excel—to draw in more varied private investment and generate near-term demand for American-built ships and related products—including software, engines, fueling systems, and port infrastructure.

To get started, the United States should consider these three recommendations:

1) Using public funds to unlock private sector investment, and keep it durable

Focusing on standards, shared assets, and talent can help reduce long-run dependence on subsidies and attract more domestic and foreign investment.

A. Develop a Maritime Security Trust Fund: Establish an end-to-end commercial fund structure to pool annual appropriations, dedicated maritime fees, matching grants from public-private partnerships, and reinvested returns—enabling multi-year planning, flexible instruments (grants, loans, equity-like vehicles), and disciplined portfolio management for maritime security and resilience.

Potential owners: Congress, Department of Transportation (DOT), Maritime Administration (MARAD), Department of the Treasury, US Coast Guard (USCG), Office of Management and Budget (OMB), port authorities, and private investors.

Useful metrics: Annual inflows and outflows, leverage ratio (public-to-private), portfolio return and reinvestment rate, allocation to priority missions, time from application to disbursement, default and delinquency rate on repayable instruments, and administrative cost ratio.

B. Tie funding to standards to unlock scale: Link grants and credit to common technical specifications (such as port data layers, digital twins, autonomy, fuel handling, and bunkering). Align USCG guidance with classification society rules to ensure projects remain on predictable paths

Potential owners: DOT, MARAD, USCG, and Department of Energy (DOE).

Useful metrics: Share of funded projects certified to common specifications; median time‑to‑approval versus baseline.

C. Focus on enabling inputs: Prioritize public funds where markets underprovide (for example, R&D, testbeds, pre-competitive port data infrastructure) and where investment can boost productivity across multiple projects.

Potential owners: Congress, DOE, DOT, MARAD, and National Science Foundation.

Useful metrics: Throughput gains at funded yards; third-party adopters of funded tools.

D. Grow talent for the stack being built: Create apprenticeships, scholarships, and international exchanges in electrics, controls, AI, composites, cybersecurity, and port automation to serve autonomy, alternative fuels, and smart ports. Allow for portable credentials across maritime and logistics employers to increase flexibility.

Potential owners: Department of Labor, state systems, unions, and maritime academies.

Useful metrics: Number of placements, wage growth, credential completion, and employer demand.

E. Modernize rules to accelerate learning: Create regulatory sandboxes for autonomous vessels and implement streamlined licensing for alternative fuels—paired with transparent safety‑case templates and post-trial learning reports—to support safe experimentation with fast feedback.

Potential owners: USCG (with classification societies), Environmental Protection Agency or DOE (for fuel), and port authorities.

Useful metrics: Number of pilots approved, incidents per operating hour, average time from application to authorization.

F. Create cost-sharing agreements with shipyards and companies building new markets: Develop joint funding models that de-risk modernization and capacity projects—for instance, milestone-based federal payments, matching grants, and repayable advances tied to delivery—so public dollars crowd in private capital and accelerate shipyard upgrades and the development of new market technologies.

Potential owners: DOT, MARAD, Department of Defense (DOD) (where relevant), state economic development agencies, and port authorities.

Useful metrics: Federal-to-private leverage ratio, number of shipyards participating, time to financial close, milestone on-time rate, projects delivered on budget and schedule.

G. Incentivize domestic supply chains: Offer targeted tax incentives and access to purchase programs for critical components—paired with supplier development and certification support—to expand US manufacturing capacity, shorten lead times, and reduce import dependence.

Potential owners: Department of Commerce (DOC), Department of the Treasury, Internal Revenue Service, DOD, DOT, MARAD, Small Business Administration, and state manufacturing programs.

Useful metrics: Share of domestic content in projects, number of US suppliers added or qualified, average lead-time reduction, value and volume of guaranteed purchase agreements executed, dual-sourcing rate for critical parts, and waiver rate under domestic-preference rules.

2) Creating new investable markets

Investors fund projects that are clear and scalable. Templates, test ranges, aligned fees, and predictable procurement are a few ways to create investable projects in autonomy, alternative fuels, and smart port tech—with spillovers beyond maritime that help reduce overall risk.

A. Up-front clarity on standards and governance can lower investor risk: Create templates, models, and protocols to jumpstart industry activities. For instance, a safety‑case template for autonomy (including operational modes, remote oversight, fail-safes, and cybersecurity baselines), a reference data model for port digital twins, and a fuel‑handling protocol family. All these should be aligned with the USCG and classification societies.

Potential owners: USCG (and classification societies), port authorities, and standards bodies.

Useful metrics: Number of insurers offering coverage based on the template and interoperable deployments.

B. A national test range with shared data: Establish a formal autonomy and alternative fuels test range (covering coastal and port environments) that uses common data and reporting, and publishes anonymized performance data sets to speed learning and lower vendor due‑diligence costs. Government funding incentives can be used to encourage participation.

Potential owners: USCG and DOT with state partners and classification societies.

Useful metrics: Participating firms, test hours, and defect‑closure rates.

C. Fees aligned with performance and public goods: Conduct independent reviews of ship, trade, and harbor fees to reward throughput, safety, and resilience via smart port, alternative fuel, and autonomy adoption. These can be tested through pilot programs at willing ports to encourage the development of these new markets while accounting for the private sector’s implementation cost.

Potential owners: Port authorities and state transportation agencies.

Useful metrics: Turn‑time improvement, resilience score, and trade throughput.

D. Prosperity zones for maritime innovation: Encourage the development of zones intended to attract private sector investment around ports and shipyard clusters with clear goals (such as jobs, throughput, and community infrastructure)74 and simple quarterly reporting requirements to ensure goals are being met. For technology investments specifically, eligibility should be technology-neutral but include incentives to drive investment and standards development around autonomy, alternative fuels, and smart ports, not just hulls.

Potential owners: DOC, in coordination with states, port authorities, the Department of the Treasury, DOT, and the Department of Homeland Security

Useful metrics: Zone key performance indicators, community development indicators dashboards, and independent annual audits.

E. Low‑friction on‑ramps for nontraditional vendors: Innovation programs should include simple procurement pathways—such as challenge prizes converting to purchase orders, Other Transaction Authority or equivalents, and a one-stop vendor desk handling intellectual property, data rights, and security reviews—that can lower barriers for first-time suppliers and increase vendor participation.

Potential owners: DOT, MARAD, DOD (where relevant), and port authorities.

Useful metrics: Number of first-time awardees, time‑to‑contract, and share of awards outside traditional primes.

3) Building allied demand and reducing exposure to risky value chain inputs

The US alliance and partner network offers scale and supply chain security.

A. Turning standards into exports: Open, interoperable smart‑port stacks—including data platforms, cybersecurity protocols, and hardware—promoted via trade deals can make US solutions the easy default for ports modernizing, shipping autonomy, and alternative fuels worldwide.

Potential owners: US Department of State (DOS), DOC, US Trade Representative (USTR), DOT, and MARAD.

Useful metrics: Number of ports adopting the stack; third-country procurements citing US specifications.

B. Coproducing and cofinancing with trusted partners: Memorandums of understanding and trade deals that support coproduction of maritime autonomy, alternative fuels, infrastructure, and smart port technologies—and pairing US systems with allied and partner capacity where it fits—can generate reciprocal market access and shared certification. This approach could grow total addressable demand.

Potential owners: DOS, USTR, and DOC.

Useful metrics: Number of joint projects initiated; total value of coproduced systems.

C. Modernizing foreign ports via trade deals to create new demand: Supplying US-made partner‑port smart port upgrade packages—such as software, IoT sensors, cyber security solutions, and training—financed through trade deals could help raise overseas reliability and connectivity of port infrastructure, increase demand for US port tech, improve the economics of US coastal and export service, and increase trade volumes.

Potential owners: DOS, DOC, USTR, and US vendors.

Useful metrics: Throughput improvements and dwell-time reductions; US content share.

D. Establishing a ship recycling coalition: Expanding certified, high-standard ship recycling capacity in the United States can capture new work from an aging global fleet. Recycled steel may not go into new hulls, but it can supply other industries—creating additional US sources of steel and freeing domestic refineries for maritime demand—and keep shipyards active between newbuild programs.

Potential owners: Environmental Protection Agency, DOT, MARAD, and states.

Useful metrics: Tonnage processed, workforce retained, and share of recycled inputs used in the US industry.

E. Tax incentives, priority berthing, and other programs to encourage carriage of US and US-bound cargo on US ships: Implement a priority‑berthing protocol (queue‑jump) for US-flag ships over vessels linked to countries or entities of concern. Provide tax and other financial incentives for carrying cargo on US-built and flagged ships. Offer port preferences and other favorable services for foreign shipping companies that invest in US maritime products and services. Expand the use of marine highway feeder rebate programs for US-built vessels.

Potential owners: DOT, MARAD, ports, marine terminal operators, USCG, Federal Maritime Commission, and states.

Useful metrics: Average berth‑wait delta versus baseline; number of priority uses; vessel on‑time percentage; use of US-flagged and built vessels.

Seizing the future of maritime trade

The window to shape the next chapter of maritime trade is open, but is likely narrowing. While the United States cannot out-subsidize shipbuilding leaders, it can compete differently. By focusing on autonomous ships, alternative fuels, and smart ports, the United States can help shape the next wave of evolution in critical maritime trade technologies and markets. Acting now can set standards, build relationships, and compound into durable US shipbuilding competitiveness—with spillover to broader maritime competitiveness. Delaying could hand the opportunity to competitors.