Transportation trends 2025–2026: Modernizing America’s transportation infrastructure

Five key trends shaping the US transportation system, from AI and autonomous vehicles to funding, cybersecurity, and infrastructure modernization

Rob Cary

Christopher Tomlinson

Tiffany Fishman

Mahesh Kelkar

Glynis Rodrigues

For more than a century, America’s transportation system has carried people, goods, and ideas across the nation, stitching together communities and regional economies. Today, however, that legacy could be at risk.

Deferred maintenance, growing cyber vulnerabilities, antiquated technology, and more frequent and intense weather events are impacting an aging network of roads, bridges, rail, runways, and transit lines. The American Society of Civil Engineers’ 2025 Infrastructure Report Card assigned most of the nation’s surface‑transportation and aviation assets grades ranging from “fair” to “poor,” signaling mounting safety and reliability concerns.1

An upcoming series of major international and national events will further strain the nation’s transportation network. In June 2026, 11 American cities will welcome more than 5 million fans for the FIFA Football World Cup.2 Shortly thereafter, nationwide celebrations for the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence will include a variety of public events.3 Two years later, Los Angeles will host the 2028 Summer Olympics.4

Recent infusions of federal and state capital have slowed the decline of our networks, but sustained strategic investment is necessary to preserve the movement of people and goods for the next century.5 To help address current challenges, anticipate emerging issues, and seize future opportunities, transportation agencies should be rethinking and redefining their strategic approach.

A blueprint for change

The US Department of Transportation (DOT) plans to modernize the nation’s mobility infrastructure, ensuring safety, bridging funding gaps, streamlining regulatory oversight, improving efficiency with emerging technologies, and tapping private sector expertise to address both existing problems and new needs.6 To achieve these goals, the DOT is focusing on:

Prioritizing public safety. The DOT has requested US$22 billion for the Federal Aviation Administration to update and modernize technology for increased safety, including hiring and training up to 2,000 new air traffic controllers.7 Additionally, the DOT has recently made US$982 million available to local governments for roadway safety projects.8

Diversifying funding approaches. With traditional federal funding stretched thin, states and metropolitan agencies are experimenting with new revenue streams, including “value capture” mechanisms and long-term public-private partnerships.9 Virginia’s first-of-its-kind dynamic tolling express lanes, which were opened to traffic in 2012, have been successful.10 Other recent state public-private partnership projects, such as those in Tennessee and Georgia, which aim to develop miles of express lanes and provide significant upfront payments to the states while allowing concessionaires to recoup their investments through tolls, point one way forward.11

Regulatory agility. At the federal level, DOT aims to reduce the regulatory burden for critical infrastructure projects, allocating US$9 million in the fiscal 2026 budget to the Interagency Infrastructure Permitting Improvement Center to streamline permitting reviews. The administration is identifying regulations that contribute to delays while focused on safety. These changes aim to facilitate quicker, more efficient project completion.12

Five trends shaping transportation in 2025–2026

This year’s Transportation Trends report delves into five key trends shaping America’s transportation agenda:

- Diversifying transportation funding models. Flat federal outlays and growing needs are intensifying the search for stable, long-term revenue solutions. Many states are expanding tolling, introducing new electric vehicle taxes and fees, implementing mileage-based user fee pilots, adopting congestion pricing, and creating public-private partnership agreements to address the widening funding gap.

- Scaling artificial intelligence in transportation. AI-enhanced operational platforms are shifting from pilots to production. AI applications are helping to cut congestion times, improve predictive maintenance capabilities, offer insights into commuter behavior, and monitor transportation infrastructure in real time. One of the challenges lies in finding ways to scale innovations beyond pilots and experiments—creating mature, robust systems that keep pace with evolving user and operational needs.

- The promise of autonomy. Autonomous vehicle (AV) technology is edging into commercial service, with robotaxi pilots on the streets in several cities.13 Government planners and policymakers worldwide are assessing how to safely integrate AVs—including autonomous trucks—into transportation ecosystems.

- Making transportation cybersecure. The rapid convergence of information and operational technologies is creating new and increasingly sophisticated cyber threats for transportation planners and policymakers. Transportation agencies should mature their internal cyber capabilities and enhance cybersecurity measures throughout their extended vendor ecosystems.

- Future-proofing transportation infrastructure. Designing for physical resilience, catalyzing innovation, and leveraging technology to improve planning and maintenance can extend asset lifespan and help contain life cycle costs.

Trend 1: Diversifying transportation funding models

Evolving economic conditions, technological advancements, and shifting consumer behaviors have changed the landscape of transportation funding significantly in recent years. As gasoline tax revenues decline, states continue facing the challenge of maintaining and enhancing their transportation infrastructure. State transportation agencies, moreover, may need to adjust to new federal priorities. The DOT aims to improve efficiency in delivering road and bridge infrastructure projects while focusing on safety and addressing local and regional needs.14 Additionally, proposed modifications to funding grant formulas may require some states to find new ways to balance funding priorities with federal guidelines.15

Changing vehicle preferences, federal policies, and work trends can have downstream effects on public transportation

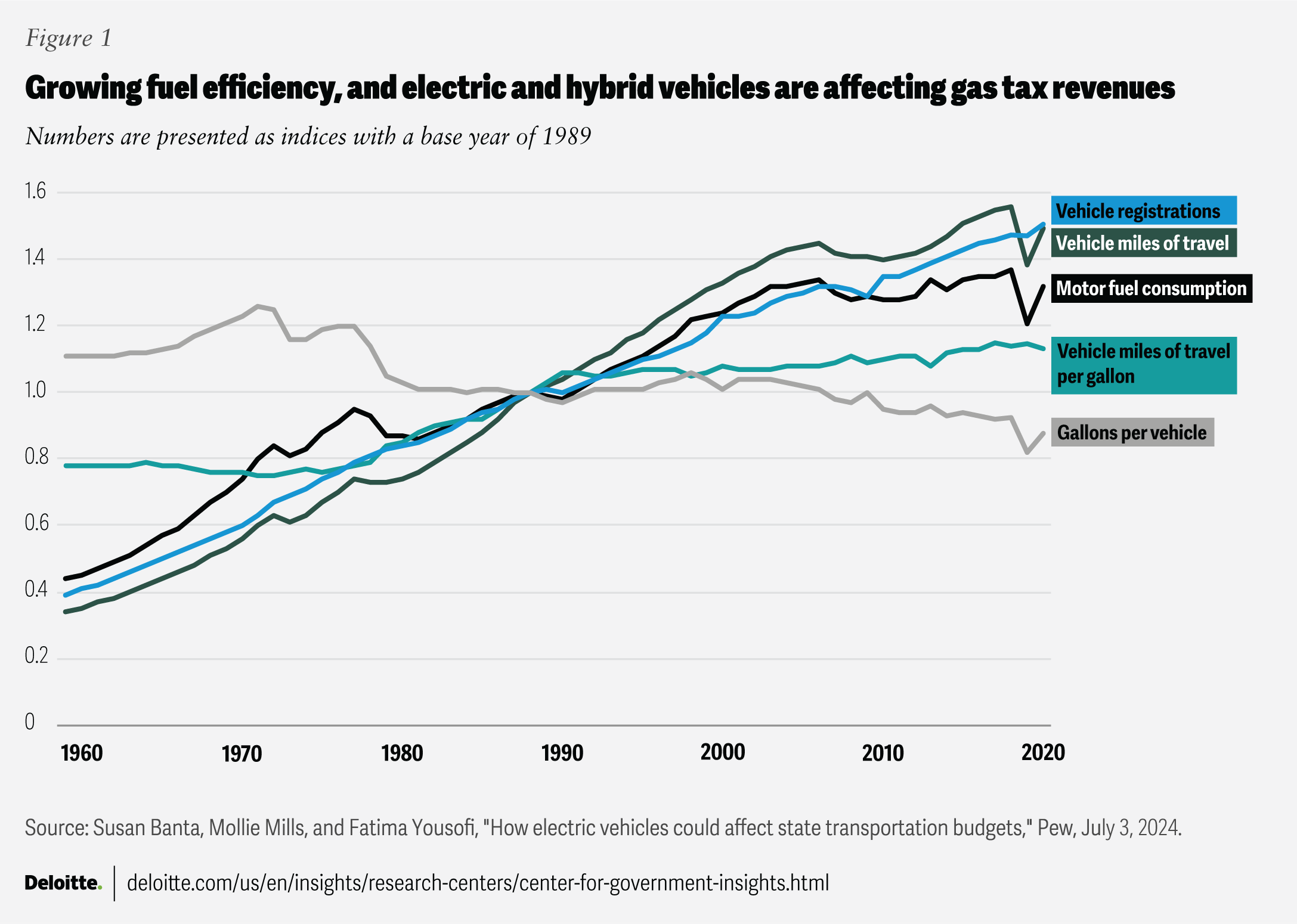

The growing efficiency of conventional vehicles and increased sales of electric and hybrid vehicles have created challenges for state transportation agencies that rely heavily on gasoline tax revenues (figure 1).16 The Congressional Budget Office estimates that tax receipts from the federal gasoline tax will fall by 39% over the next decade, from US$25 billion in 2025 to US$15 billion in 2035.17

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that tax receipts from the federal gasoline tax will fall by 39% over the next decade, from US$25 billion in 2025 to US$15 billion in 2035.

However, DOT recently began easing the corporate average fuel economy standards—which dictate how far a vehicle must travel on a gallon of fuel—and the administration has ended certain electric vehicle incentives.18 Both policies will have downstream effects on car prices and gas tax revenue in the near term.

Changing economic and societal conditions also play a role in transportation funding. The global COVID-19 pandemic reshaped many transportation habits, with remote work reducing the number of vehicles on the road and lowering fuel consumption. Data from the Council of Economic Advisers points toward a dramatic shift in the share of remote work in the overall economy between 2019 and 2024.19

The share of paid days worked remotely rose from 7.2% in 2019 to 27.7% in 2024, as did the share of workers on hybrid and fully remote schedules.20 Between 2019 and 2023, the proportion of people who did not have to commute increased by 8 percentage points (from approximately 7% to 15%), with an obvious effect on personal vehicle and public transportation usage.21 The impact of remote work varies by region, with Washington, Oregon, Colorado, Arizona, Virginia, Maryland, Massachusetts, and Washington, D.C., having among the highest shares of remote workers.22

The share of paid days worked remotely rose from 7.2% in 2019 to 27.7% in 2024; the share of workers on hybrid and fully remote schedules also rose. Between 2019 and 2023, the share of people with no commute time increased by eight percentage points, which has an obvious effect on personal vehicle and public transit usage.

The return to office trend continues to evolve, however, many large organizations including the federal government have mandates requiring employees to work in the office full time.

Multiple approaches to diversify transportation funding

Many states are exploring various strategies to plug funding gaps, including adjusted gas tax rates, fees and taxes on EV purchases, road-user charges, and public-private partnerships.

Modeling budget shortfalls

Few state transportation agencies have modeled how EVs will affect revenues in future years or quantified the anticipated shortfalls. Only a handful have adopted a data-driven approach, quantifying future shortfalls before developing alternative funding streams.23

California is modeling the impact of rising zero-emission vehicles on transportation funding. Its Legislative Analyst’s Office estimates that transportation revenue will decline by US$4.4 billion (31%) in the next decade. This decline could be further exacerbated by plans to end gasoline-powered passenger car sales in the state by 2035.24

Another factor impacting future revenue projections is the usage of state roads and other infrastructure by nonresident vehicles traveling across state lines. In Tennessee, gas taxes and vehicle registration fees accounted for almost 54% of total road funding in the state in 2019, and 30% to 40% of the state’s gas tax revenue was generated by nonresident drivers passing through the state.25

Road usage charging systems struggle to scale

Four states—Utah, Oregon, Virginia, and Hawaii—have implemented mileage-based user fees; the programs are voluntary and in lieu of other taxes or fees.26 Another 37 states are piloting or studying road-usage charging, either as part of a multistate coalition or as individual state pilots.27

To date, none of these pilots has successfully scaled to broader implementation, primarily due to the cost and complexity involved in administering a road user charge system.28 This system, which calculates the tax owed by each driver, is likely to entail significantly higher administrative and equipment costs compared with gas taxes. Gas taxes are more efficient due to their lower administrative costs.

Some states are trying to reduce administrative costs by employing existing vehicle safety checks to track mileage. Hawaii, for example, now records odometer readings for electric vehicles as part of annual safety inspections.29 Some other low-tech solutions are being tested; Utah’s road user charge allows drivers to upload photos of odometer readings quarterly.30

Some state transportation agencies also have found it difficult to define the value proposition for their various stakeholders. Challenges include achieving urban-rural parity in usage charges, setting data governance requirements for vehicle manufacturers and dealerships, addressing privacy concerns, and building public trust in these systems.31

EV taxes and fees

The increasing popularity of EVs and hybrid vehicles presents both opportunities and challenges for transportation funding. Low- and zero-emission vehicles contribute to a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and reduce dependence on fossil fuels, but their increasing adoption poses a challenge to traditional funding models reliant on gas taxes.

At least 41 states have enacted special registration fees on EVs to compensate for the loss of gas tax revenue. Of these, 34 also assess special registration fees for hybrid vehicles.32 These charges have been levied in different ways and forms, but most are unlikely to fully compensate for the loss in gas tax receipts.33

At least four states—Georgia, Iowa, Montana, and Utah—have introduced a tax on electricity used to charge EV vehicles.34 This tax, a variation of road usage, is based on the units of electricity used. Further research and time for adoption are needed to fully understand the efficacy and ease of implementation of this approach.

Congestion pricing

Congestion pricing can be a powerful tool for managing traffic and easing urban congestion. In addition to these potential benefits, it can provide an alternative funding mechanism for cash-strapped states and urban centers.

Internationally, cities such as London, Singapore, and Stockholm have reduced congestion by 13% to 30% and greenhouse gas emissions by 15% to 20% through these methods.35 London has introduced a multilayered approach comprising three distinct charge categories: a charge to tackle congestion in central London; a low-emission zone to target air pollution across Greater London; and an Ultra Low Emission Zone to target older, more polluting vehicles. In 2023, the three categories of charges generated a net income of 431 million pounds for the city. This revenue is used to upgrade and develop London’s public transport and infrastructure.36

In January 2025, New York City launched its own congestion pricing program. The program charges passenger vehicles, trucks, and buses a flat fee to enter the business districts during peak hours, and charges are reduced by 75% at night. The program aims to reduce traffic and travel time, cut emissions, improve quality of life, and raise revenue for public transportation improvements.37 While the changes have led to mixed outcomes such as reducing traffic in business districts but increasing it in some other areas,38 they also generated a net operating revenue of US$215.7 million in the first four months of operations.39

Reimagining public-private partnerships to plug the funding gap

As fuel tax collections wane, many agencies are tapping into private sector capital to build and maintain highways, roads, and bridges.

By partnering with private entities, state and local governments can share both the risks and rewards of large-scale projects. Public-private partnerships for dynamically priced managed lanes have been operating in the US for more than a decade. Virginia opened its first 14 miles of managed express lanes in 2012. Today, it operates a 65-mile network. In their first decade, these lanes saved local travelers 33 million hours in travel time while creating US$8 billion in economic activity.40

Georgia’s State Route 400 project is harnessing private expertise to expand and modernize a critical roadway while optimizing cost and construction timelines.41 In August 2024, the Georgia Department of Transportation picked a consortium to build 16 miles of express lanes along Atlanta’s highways. The US$4.6 billion project is a 55-year contract to design, build, finance, operate, and maintain the infrastructure, with plans to recoup investments through tolls.42

Tennessee, too, plans to create “choice lanes” using dynamic tolling to manage congestion and generate revenue, with initial funding from the state’s Transportation Modernization Act.43 Commuters on the Interstate 24 routes between Nashville and its suburbs will have a choice between paying for convenience or facing congestion using free, general-use lanes.44

Trend 2: Scaling AI in public transportation

US transportation departments already collect vast amounts of information from traffic signal timings, sensor feeds, GPS data, rider feedback, and more. Due to advances in AI and analytics, today, they have the tools needed to harness this information, uncovering insights from travel patterns, using sensor data to enhance service quality, and improve operational efficiency.

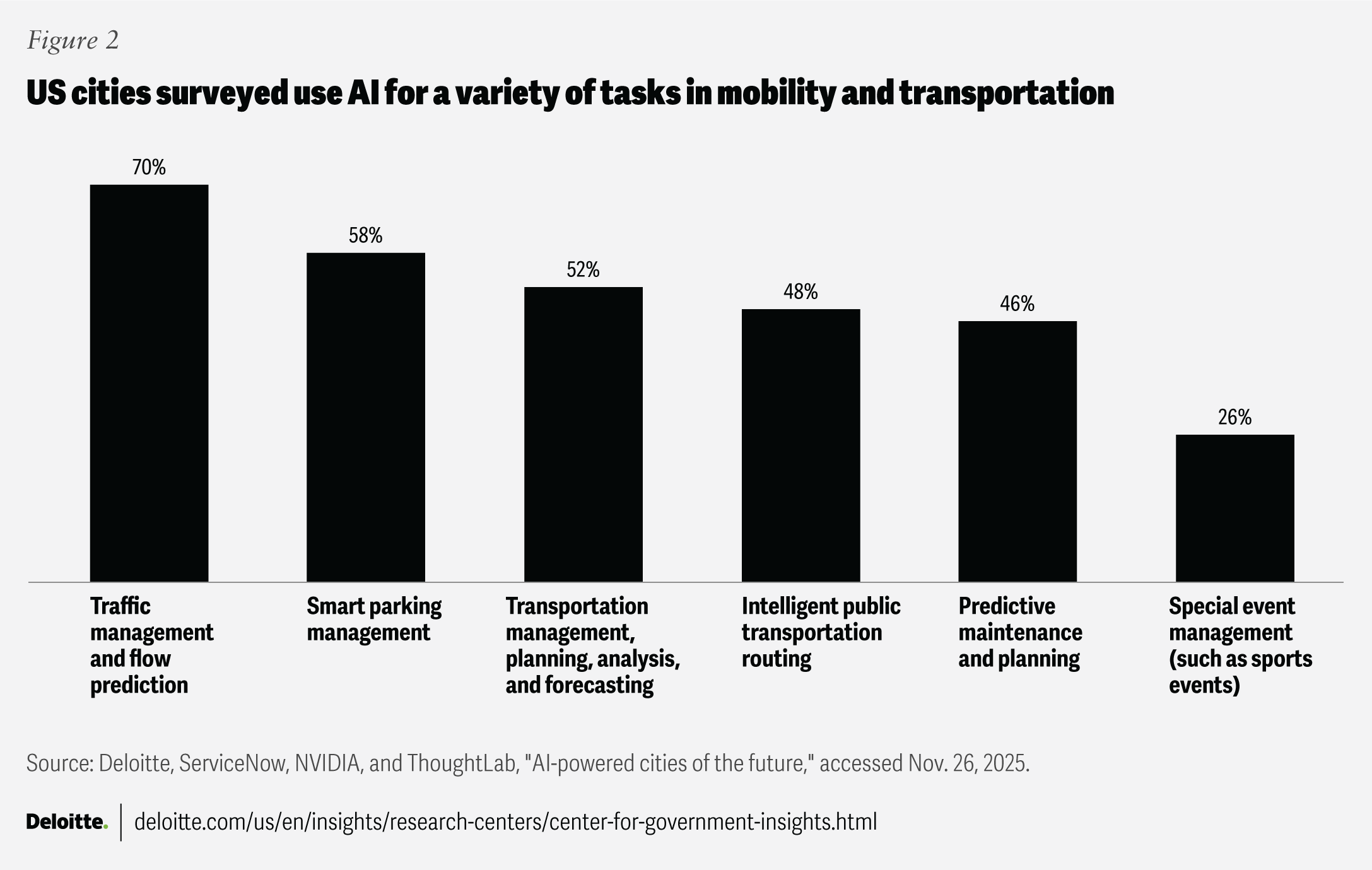

AI can provide insights into what riders may need, allowing transportation authorities to offer tailored services. It can monitor road conditions and transportation infrastructure in real time, so any incidents are addressed promptly. A recent Deloitte-ThoughtLab survey of global city leaders found that some US cities already use AI for traffic management, smart parking management, transportation planning and forecasting, and intelligent routing (figure 2).45 And AI’s convergence with other technologies, including digital twins, data analytics, biometrics, and cloud computing, seems to be increasing its promise.46

For most government agencies, the challenge is not data availability, but rather their ability to harness it effectively to unlock useful information from departmental silos and convert it into actionable insights.47

Many transportation leaders and planners seem to recognize the benefits AI offers, and a number of pilot projects and proof-of-concept initiatives are underway. The challenge now lies in finding ways to scale innovations beyond pilots and experiments—creating mature, robust systems that keep pace with evolving user needs.

AI creates value for transportation agencies

Some of the most common uses for AI in transportation include smart parking, smart signals, route optimization, and traffic compliance. But advances in data management and AI technologies could allow transportation agencies to build predictive capabilities, improve planning and design, and make more dynamic and accurate real-time decisions.

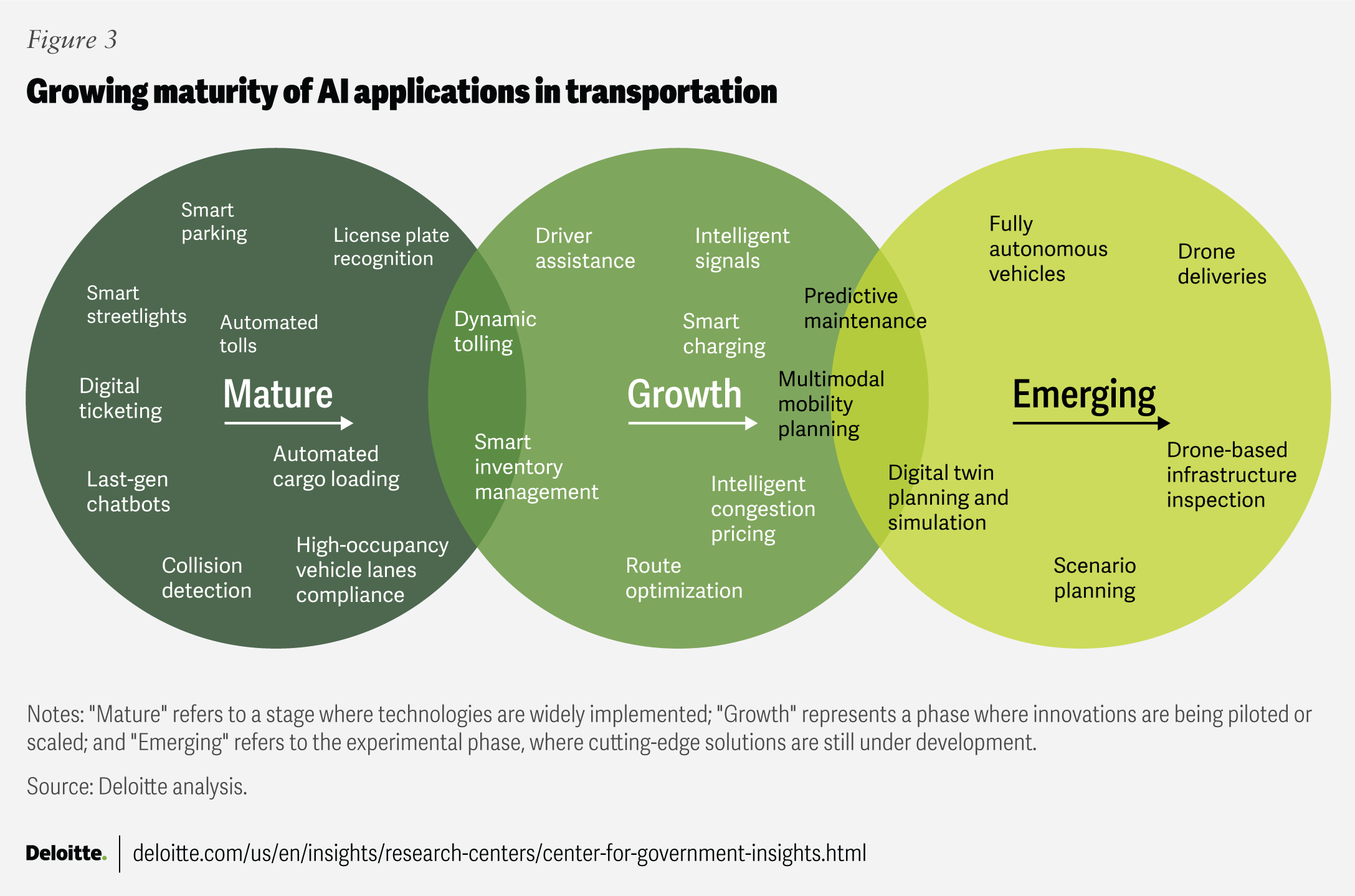

Depending on the maturity of AI applications, usage in transportation can be categorized broadly by the value it creates for transportation agencies (figure 3).

Mature AI applications

Smart parking: The nationwide surge in traffic has prompted agencies to rethink urban parking infrastructure.48 The earliest smart parking innovations began with sensors placed in parking lots to gauge space availability. Now, advanced AI technologies can help analyze real-time traffic and occupancy data and historical parking patterns to help agencies adjust parking fees dynamically in response to congestion.

The Seattle Department of Transportation has linked 2,200 parking pay stations to a state-of-the-art pay-by-plate system, offering a suite of payment options and using real-time occupancy data to optimize enforcement and deliver custom digital notifications. The system allows transportation planners to monitor transactions in real time and extract detailed information by area. Seattle adjusts prices for these spaces quarterly across 30 different rate zones, ensuring efficient use of parking space and sustaining smooth traffic flows.49

Compliance: New York City’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority is rolling out a sophisticated camera system on its buses designed to discourage vehicles from obstructing dedicated bus lanes. Mounted on the interior of bus windshields, the dual-camera system can capture license plate details as well as contextual video footage. The system supports the enforcement of bus lane regulations that help maintain clear corridors for more than 15 million regional commuters. By late 2019, after its first two months of implementation, it had detected 9,700 violations and helped increase commuting speeds by 55%.50

Safety: California plans to integrate AI into traffic management on its highway network. The envisioned real-time data ecosystem, based on an expansive network of sensors, weather stations, and cameras, will support generative AI applications aimed at reducing traffic congestion and preventing collisions. Officials anticipate a system capable of issuing immediate alerts directly to drivers’ phones or dashboards, giving them time to react to hazards such as dense fog or wrong-way drivers.51

Growing AI applications

Smart signaling: Authorities in Arlington, Texas, use a platform that taps data from sensors and cameras to sync traffic signals with real-time conditions, adjusting them as needed. For example, it can lengthen yellow lights or prioritize emergency vehicles. The system also provides planners with detailed traffic data that can help them respond quickly to new challenges.52 In a two-month pilot project in Redlands, California, a similar system tested at just two intersections saved 900 commuting hours and cut 11 tons of vehicle emissions.53

Predictive maintenance: New York City’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s TrackInspect prototype uses advanced AI to detect subway track defects. Smartphones retrofitted in subway cars capture vibrations and sound patterns through built-in sensors and microphones, sending the data in real time to cloud-based systems. AI and machine learning algorithms generate predictive insights that are sent to track inspectors for human inspections. Inspectors examine detected defects, confirm issues, and allow the model to keep learning. Furthermore, a gen AI layer helps inspectors ask questions about maintenance in natural language. The initial pilot ingested and analyzed 335 million sensor readings, one million GPS locations, and 1,200 hours of audio, detecting 92% of defect locations found by inspectors.54

Route optimization: Tennessee’s Chattanooga Area Regional Transportation Authority, in collaboration with Cornell researchers, is pioneering an AI-driven initiative to create “mobility zones” that integrate buses, shuttles, electric vehicles, and bikes into a single intelligent system, analyzing real-time transit data and user preferences to provide personalized route and mode recommendations. The program aims to increase public transit usage from 1.6% to 5% and reduce energy consumption by 10% per person.55

Emerging AI applications

Transportation infrastructure planning: AI technologies can accelerate value for transportation agencies in combination with other important foundational technologies. One such technology, “digital twin,” can transform the sector by providing a detailed virtual representation of physical assets and systems, allowing for simulations and optimization.

By integrating data from varied sources, including sensors, historical records, and commercial, digital twins can offer a comprehensive view of the current and likely future condition of these assets.

In Florida, the Broward Metropolitan Planning Organization is developing a digital twin called SMART METRO, designed to merge data on housing, zoning, population, and climate to improve infrastructure planning. SMART METRO is expected to be able to forecast congestion and flood risks while simulating transportation and land-use impacts. Planners should be able to ask the system questions in plain language and employ geospatial visuals to develop ideas. The organization plans to use it to guide redevelopment projects, improve roadways, and identify optimal locations for transit stops and routes.56

Drone-based deliveries and inspections: The Massachusetts Department of Transportation’s Aeronautics Division is piloting a program that will evaluate the use of drones to deliver medical supplies to critical locations, potentially minimizing delays during emergencies. Another pilot involves using drones to inspect assets in hard-to-reach areas along transportation routes. These methods could improve service delivery and streamline infrastructure maintenance.57

Early cases for generative and agentic AI transformation in public transportation

The transportation industry is actively exploring the potential of generative AI, which can automate many tasks, analyze mountains of data, and create and edit text, video, and images. In Deloitte’s recent survey of transportation and supply chain executives across sectors, more than 40% of responding government and public services executives said that gen AI is already transforming their industry.58

In May 2024, the California Department of Transportation issued contracts for pilot programs to test how gen AI can enhance traffic operations and road safety, making data from sensors, real-time camera feeds, and other sources usable for transportation planners.59 The first pilot will use generative AI to investigate near-miss incidents, identify hazardous areas, and aid workers in brainstorming ideas to protect bikers and pedestrians. A second pilot will analyze traffic choke points, with the aim of reducing congestion and enhancing crash prevention by generating real-time route adjustments or alerting operators to hazards.60

The emergence of agentic AI—AI that can operate independently and make autonomous decisions—may redefine public transportation even further.61 Agentic AI can accelerate the development of intelligent transportation systems by rerouting traffic during accidents, adjusting signal times based on traffic flow data, triggering predictive maintenance workflows, and coordinating vehicle-to-vehicle and vehicle-to-infrastructure communication.62 The technology is still in its early stages, and important questions concerning human oversight, cybersecurity, and interoperability remain to be resolved.63

Navigating the scaling AI challenge

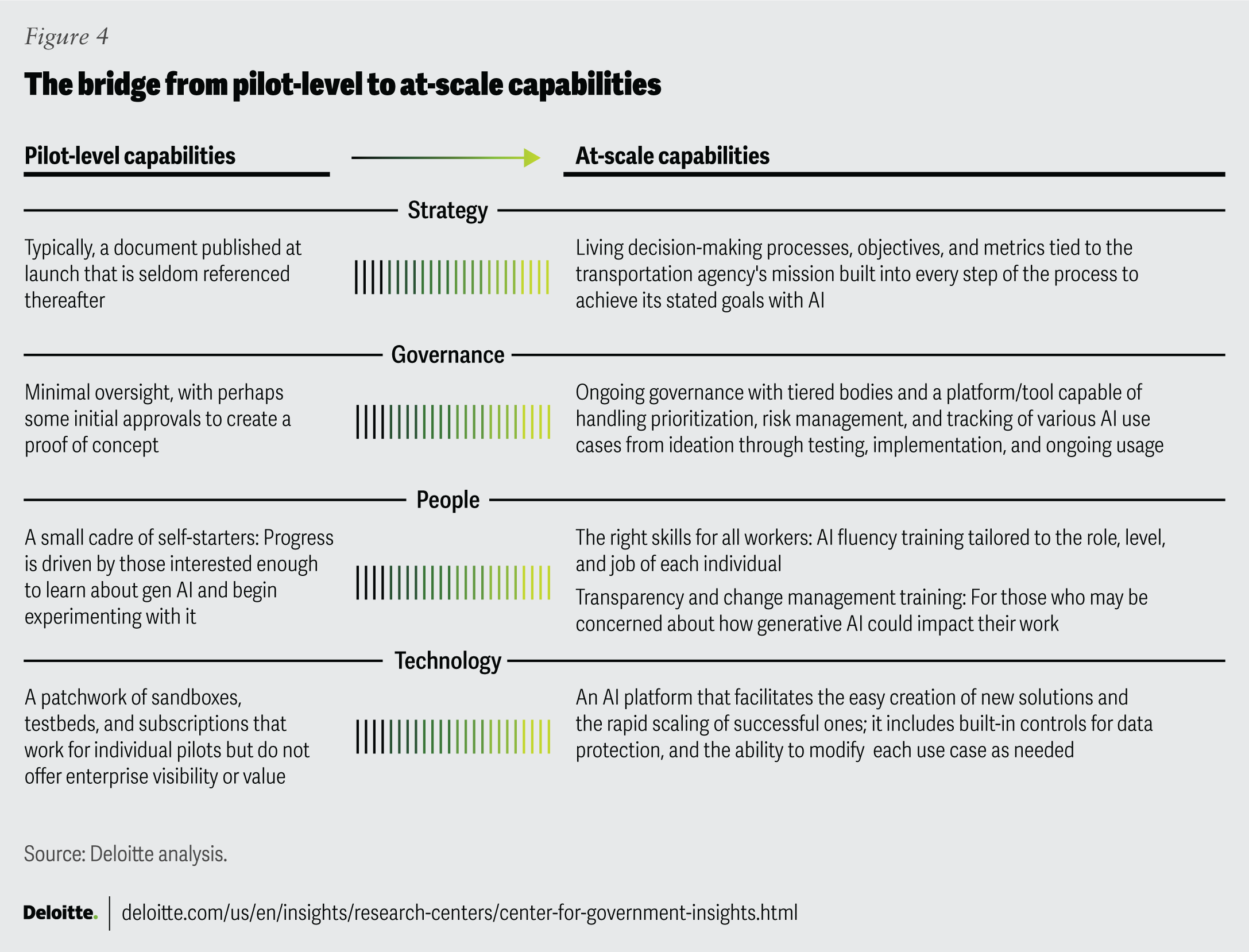

While pilot projects may provide valuable insights during initial experimentation, widespread, scalable AI applications may require a far more integrated and comprehensive approach.

The level of expertise, infrastructure, and coordinated governance needed to fully embed AI into transportation processes far exceeds the requirements of early-stage experiments. This disparity underscores the importance of a concerted effort to move from preliminary projects to robust, scalable solutions that can drive efficiencies, enhance service reliability, and lead to a smarter, more responsive transportation network.

The integration of AI in transportation hinges on four critical dimensions: strategy, governance, people, and technology (figure 4). By addressing these four dimensions broadly, transportation executives may be able to better ensure that AI initiatives become integral to their systems.

Trend 3: The promise of autonomy

After years of optimistic predictions, as well as skepticism,64 autonomous vehicles are finally cruising our city streets, highways, and industrial sites.

The potential economic and social benefits of driverless cars—beginning with improved efficiency, convenience, safety, and mobility—have long been evident.65 One study estimated that using AVs to optimize traffic flow and dissipate stop-and-go traffic patterns would yield a 40% reduction in fuel consumption and a 15% increase in vehicle throughput.66 A simulation conducted by the International Transport Forum at the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development suggested that shared AV taxi and micro transit fleets could drastically reduce a city’s congestion, emissions, and parking space requirements.67 Additionally, AVs can help those who can’t drive due to disabilities or advancing age.68

Autonomous technology could also create new job opportunities. The Chamber of Progress estimates that deploying 9 million AVs in the United States during the next 15 years would create more than 114,000 jobs in AV production, distribution, maintenance, upgrades, and repairs.69

Even if most states and nations are years away from seeing driverless vehicles at scale on city streets, government transportation leaders and policymakers should determine their key objectives and priorities—such as fewer crashes, less congestion, lower parking demand, improved air quality, and economic development—and consider how AVs might contribute to achieving them.

Ready for the spotlight: Autonomous technology

Technology and automobile companies are expanding autonomous vehicle pilots, such as robotaxis, in Austin, Phoenix, San Francisco, and Los Angeles.70 Autonomous vehicles have now carried passengers for millions of miles without a human driver onboard.71

When Waymo, an AV innovator, began operations in Los Angeles in 2024, around 300,000 people were on its waitlist.72 Today, anyone with the app can use the service and opt for “no-person pick-up.”73 In April 2025, the company recorded more than 250,000 paid rides per week across all four cities where it operates.74 The company now plans to introduce a next-generation AV equipped with custom sensors and an AI “driver.”75 In all, the AV growth trajectory remains promising, as increasing investments underscore confidence and accelerate the development of autonomous vehicle technology.76

This technology is also proving valuable in the logistics industry.

In Austin, the Texas Department of Transportation has partnered with a technology company to develop America’s first autonomous trucking corridor, which will span 21 miles. This smart road will be fitted with sensors to monitor real-time traffic and road conditions, alerting connected vehicles to advisories and traffic incidents, thereby creating safer and more efficient conditions for autonomous trucks.77

The adoption of autonomous trucks has increased significantly in recent years, particularly in the mining industry. As companies realize the benefits of increased productivity and reduced operating costs, the trend is growing worldwide. In 2024, Australia led the world with 927 of a total 2,080 autonomous haul trucks operating in mines, followed by China, Canada, and Chile.78

Despite such advancements, several obstacles could hinder the widespread adoption of AV technology, including the absence of applicable regulations, a lack of public trust, the need for better safety standards, and improvements to existing infrastructure.79

A proactive regulatory approach to scale AVs

AVs will likely need a higher level of public trust for widespread adoption. Achieving this may require a coordinated effort across the broader transportation ecosystem, combining the strengths of the public and private sectors to ensure safety and reliability, to nurture public confidence.

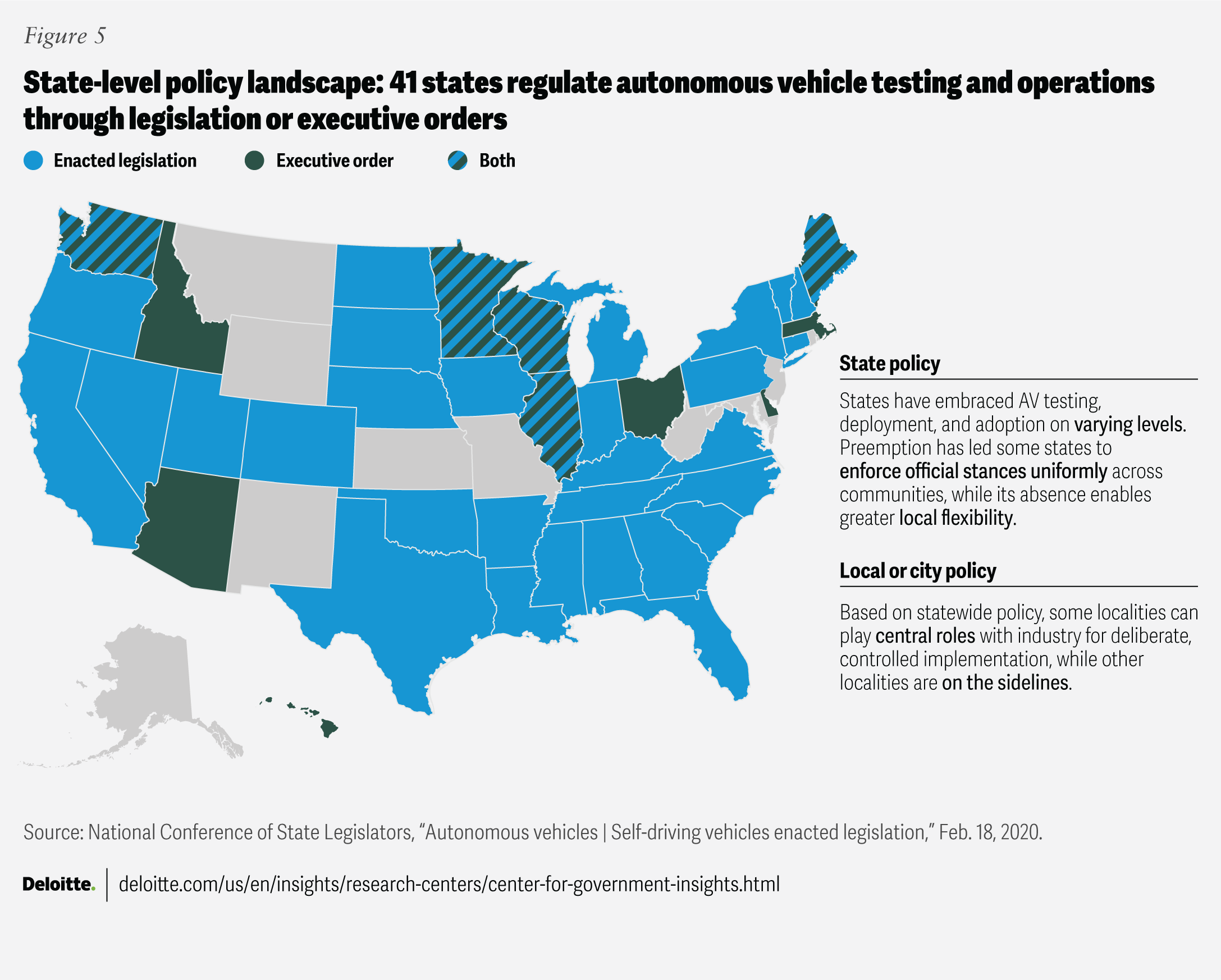

What could be needed is a multilayered approach to governance. Federal regulators are charged with setting software safety testing standards, while state and local policymakers can tailor plans to maximize the benefits of AVs within their regions.80 To date, most states have enacted legislation primarily focused on testing, with 25 states allowing some level of AV deployment and 41 states having passed related legislation or issued executive orders (figure 5).

Regulators and policymakers will need to address a wide range of issues to unlock the full potential of AVs.

Yet the transportation ecosystem is so complex that even grasping its scale and the number of players can be a real challenge, and it surfaces many subject areas and questions that need attention.

Key considerations across policy areas

- Licensing, permits, and registration: How can processes be established for determining operational eligibility for AVs, and what else needs to be built out?

- Liability and insurance: What stakeholders are involved in AV operations, and who is responsible if something goes wrong?

- Road safety and traffic management: How should local governments leverage their traditional authority in traffic management, street design, and curb management to shepherd AV deployment?

- Data privacy and cybersecurity: How can AV companies share emerging findings and progress with the public sector while maintaining user privacy?

- Vehicle standards and environment: To what extent do autonomous operations require special standards, and what level of stringency will optimize safety and innovation?

Each policy area could benefit from a particular blend of oversight and collaboration among public and private entities.

Advanced air mobility

As the number of AVs on land increases, the number of autonomous drones and unmanned aerial vehicles is rising as well. Several industry players are working on automated, electrically powered advanced air mobility (AAM) aircraft that can take off and land vertically.

AAM has received growing interest and investment in recent years. According to Deloitte research conducted with the Aerospace Industries Association, the US AAM market could reach US$115 billion annually by 2035, creating more than 280,000 jobs.81

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is working closely with NASA to ensure that AAM is integrated seamlessly into the broader transportation ecosystem, while promoting regulatory consistency and upholding the highest safety standards.82

Industry players may see greater near-term opportunities in cargo transportation and military applications. In 2024, the US Army Applications Laboratory awarded a contract to a couple of private technology companies to develop an uncrewed blood delivery and casualty evacuation system.83 In the same year, the United Arab Emirates placed an order for 200 unmanned helicopters for its Ministry of Defence.84

Autonomous drones are also being tested to deliver packages, food, and other items more quickly and efficiently than traditional delivery methods.85 The FAA-authorized Wing service, owned by Alphabet, has conducted more than 350,000 deliveries across three continents. Its autonomous drones require minimal human interaction from takeoff to delivery at drop-off locations.86

Other companies plan to retrofit existing aircraft with continuous autopilot systems that would use precision navigation to cover all stages of the flight.87 These technologies could enhance the safety of current operations by preventing avoidable accidents and fuel mismanagement.88

All in all, advanced air mobility could offer a viable alternative to traditional helicopters and ground transportation for urban and regional travel.89 They’re only likely to reach the masses when operators can provide per-seat pricing on par with premium taxi services—a price point a Deloitte study revealed could be possible.90

Building trust in autonomous vehicles

A 2023 American Automobile Association survey found that 68% of respondents were afraid of AVs, an increase from 55% in 2022.91 Educating the public about what AVs can and can’t do, including the technology behind them, can help demystify the vehicles.

Transportation agencies can consider adopting a multifaceted approach by increasing transparency, demonstrating the effectiveness of safety standards, and showcasing the technology’s benefits in addressing transportation challenges. The following strategies can address public concerns and build trust.

Providing regular public updates and transparent communication: One strategy could be providing regular public updates on AV policies and regulatory frameworks, and clearly communicating how data collected by AVs would be used and how privacy would be protected.

Emphasizing cybersecurity measures: AVs being equipped with advanced cybersecurity protocols can mitigate fears of potential hacking or data breaches. AV manufacturers and suppliers should integrate strong security considerations throughout the development life cycle.92

Showcasing social benefits: Highlighting the social benefits of AVs could also foster trust. Detroit’s Accessibility-D self-driving shuttles for elderly and disabled residents demonstrated how this technology can have a direct, positive impact on people’s lives.93 This pilot initiative provided free rides to more than 110 locations throughout the Detroit area, from grocery stores to medical facilities.94 The Cumberland Hopper in Cumberland, Georgia, was another example of a successful AV shuttle pilot, serving 10,000 riders.95 According to a survey, 93% of riders felt safe while using the Hopper, a fully autonomous electric shuttle, and 90% cited it as a good travel experience.96

Trend 4: Making transportation cybersecure

Ransomware, malware, phishing, distributed denial-of-service attacks, GPS spoofing, and many other types of cyberattacks on transportation networks and infrastructure are becoming increasingly common and sophisticated. Users of toll collection agencies across multiple states have fallen victim to SMS phishing (smishing) campaigns executed by malicious actors who employ social engineering tactics to obtain private information, access, or funds.97 Research suggests that an exponential jump in generative AI–powered social engineering and voice phishing (vishing) attacks in the past year was driven primarily by malicious foreign adversaries.98

The convergence of information technology (IT) and operational technology (OT) in transportation will likely continue to rise, enabling direct control of physical devices such as signaling, traffic management systems, tolling booths, and automated ticketing systems. However, attacks on these systems can create real-world chaos.

As transportation agencies have strengthened their IT systems over the years, it may be time to build similar resilience in OT hardware and software. This requires not just strategic integration between IT and OT but also addressing the cyber talent gap in transportation agencies and improving interagency collaboration within and beyond national borders. Each could play a critical role in making transportation networks and infrastructure safer and more resilient.

An ever-changing landscape of cyber threats

The cybersecurity threat landscape for public transportation agencies has expanded in both the number and types of attacks.99

A text about an unpaid toll seems urgent and legitimate, and some daily toll road users end up paying it without a second thought. Smishing scams like these have become more common as cybercriminals find new ways to exploit digital communication. In 2024, the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center received more than 59,271 complaints about toll-related smishing scams.100

The modus operandi is simple. Commuters who use a toll route receive SMS messages seemingly from a legitimate tolling agency, demanding immediate payment and including a link to a fake website designed to steal personal and financial information. Residents across the United States have received such texts impersonating well-known toll collection services. Most toll agencies, however, communicate through mailed invoices, official websites, or verified customer service numbers. While some send text alerts, none demand immediate payment or request sensitive personal information via text.101

The transport ecosystem comprises a diverse range of vendors such as service, hardware manufacturers, and software providers, adding another layer of security concern. Vendors with weak cybersecurity measures could pass risk onto the transportation agencies they serve. Phishing continues to be a common tactic for malicious players targeting transportation networks; between July 2023 and July 2024, phishing attacks on transportation organizations rose by 175%. Social engineering attacks made through internal agency email rose by 133.5% and vendor email compromises by 250%.102

Phishing continues to be a common tactic for malicious players targeting transportation networks; between July 2023 and July 2024, phishing attacks on transportation organizations rose by 175%. Social engineering attacks made through internal agency email rose by 133.5% and vendor email compromises by 250%.

Autonomous and connected vehicles inhabit a data-rich, interconnected domain that intensifies cyber risk. Their continuous exchange of information with the environment and infrastructure creates multiple gateways for unauthorized access. Malware attacks on Internet of Things sensors and other embedded devices surged by 400% between 2022 and 2023.103 A successful hack could cripple critical vehicle functions, disrupt operations, and undermine public confidence in autonomous transportation. Moreover, AVs process large volumes of sensitive data, including passenger information and real-time location data. If compromised, these systems could fuel privacy violations or broader safety threats, underscoring the need for robust cybersecurity and resilience in connected platforms.

Advances in gen AI technology could create new challenges for the transportation sector. According to CrowdStrike’s 2025 Global Threat report, new gen AI tools are being combined with social engineering efforts to create highly convincing outputs such as fake personas, deepfake videos, and voice cloning.104 Generative AI is also turbocharging traditional phishing and social engineering attacks. According to emerging research, phishing messages generated by large language models have a click-through rate (54%) on par with emails generated by human experts .105

Integrated efforts to address IT-OT convergence

The convergence of IT and OT is becoming increasingly significant in the transportation sector, fundamentally reshaping the cybersecurity landscape. Traditionally, IT systems focused on managing data and information, while OT systems were dedicated to controlling physical devices and processes. As transportation systems evolve, however, these two domains are merging.

This integration allows for enhanced operational efficiencies, predictive maintenance, and improved decision-making capabilities. But it also introduces new cybersecurity challenges. The blending of IT and OT systems means that vulnerabilities in one domain may affect the other, increasing the risk of cyberattacks that disrupt physical operations. A 2021 ransomware attack on Colonial Pipeline, which supplies fuel to aviation companies and consumers on the East Coast, infected the pipeline’s digital systems. The pipeline was shut down proactively for weeks, compelling the federal administration to declare a national emergency.106

The incident underscored the importance of cybersecurity across transportation industries, including pipelines.107 Cybersecurity should be included during the design phase of transportation projects, ensuring that both information and physical systems are protected against potential threats.

The federal government is providing various resources to support public transportation agencies with their cybersecurity obligations. The Federal Transit Administration recently introduced a Cybersecurity Assessment Tool for Transit to help agencies evaluate their cybersecurity needs and develop their own cybersecurity programs.108

The DOT and the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) have emphasized a cross-sector approach to protecting operational technology. In November 2024, the TSA issued a notice of proposed rulemaking that included a sweeping set of cyber requirements for pipelines, rail operators, and airlines. The proposal defines OT cybersecurity requirements for partners and the broader vendor ecosystem, aiming to help safeguard both IT and OT systems.109

Closing the cybersecurity talent gap

As digital technologies play an ever-larger role in critical infrastructure, including public transportation, agencies expect the demand for cyber talent to increase exponentially. A recent study by the International Information System Security Certification Consortium estimated the 2024 global cyber workforce gap at 4.8 million—up by 19% over 2023—with critical infrastructure and government both more likely to report a cyber skills gap than other sectors.110 The US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency estimates that more than 570,000 cybersecurity jobs are open in the United States alone.111

The federal National Cyber Workforce and Education Strategy is intended to strengthen cyber skills in the workforce and the public sector.112 The National Science Foundation has funded the US$24 million CyberCorps: Scholarship for Service program to train a next-generation cyber workforce for the federal, state, local, and tribal governments. The program provides three years of scholarship support to cybersecurity undergraduate and graduate education, on the condition that recipients work for the government for a period equal to the length of the scholarship after graduation.113

Universities are also focused on addressing the skills gap. The University of South Florida received a philanthropic grant of US$40 million to establish a college dedicated to cybersecurity and AI certifications and degrees. The university opened the college in fall 2025 and plans to have 5,000 students enrolled by its third year of operation.114

The National Security Agency has recognized South Dakota State University as a Cyber Education Center of Excellence and routinely sends its employees there for specialized learning.115 In 2023, the university entered into a partnership agreement with the agency, allowing students to earn academic credit by working on classified projects. The agency’s employees can collaborate with faculty and students, acquiring valuable insights and keeping students informed about the latest trends in national security defense.116

Trend 5: Future-proofing transportation infrastructure

The nearly seven-decade-old US Interstate Highway System now carries far more traffic than anticipated in its original design and needs repairs.117 Many of our nation’s highways and bridges are in a similar state—aging and requiring reconstruction and modernization. According to the American Society of Civil Engineers, nearly 39% of America’s major roads are in poor or mediocre condition, while about half of all bridges are in no better than fair condition.118

The Baltimore bridge collapse in March 2024 underscored the importance of upgrading and modernizing transportation infrastructure.119 While modern safety features can be added during the design phase of new projects, retrofitting an existing bridge is far more complicated and costly.120

Today, government transportation leaders face increasingly complex challenges such as modernizing and revitalizing aging infrastructure, building resilience, and mitigating the impacts of extreme weather events. By leveraging advanced technologies, innovations in material science, and data analytics, agencies may be able to safeguard critical systems and ensure the continuity of essential transportation services.

Protecting transportation systems against extreme weather

Extreme weather events are a major motivator for resiliency planning among transportation agencies. Consider 2005’s Hurricane Katrina, which destroyed more than half of New Orleans’ bus fleet; or Boston’s snowiest winter in 2015, which disrupted transit for over 60 days.121

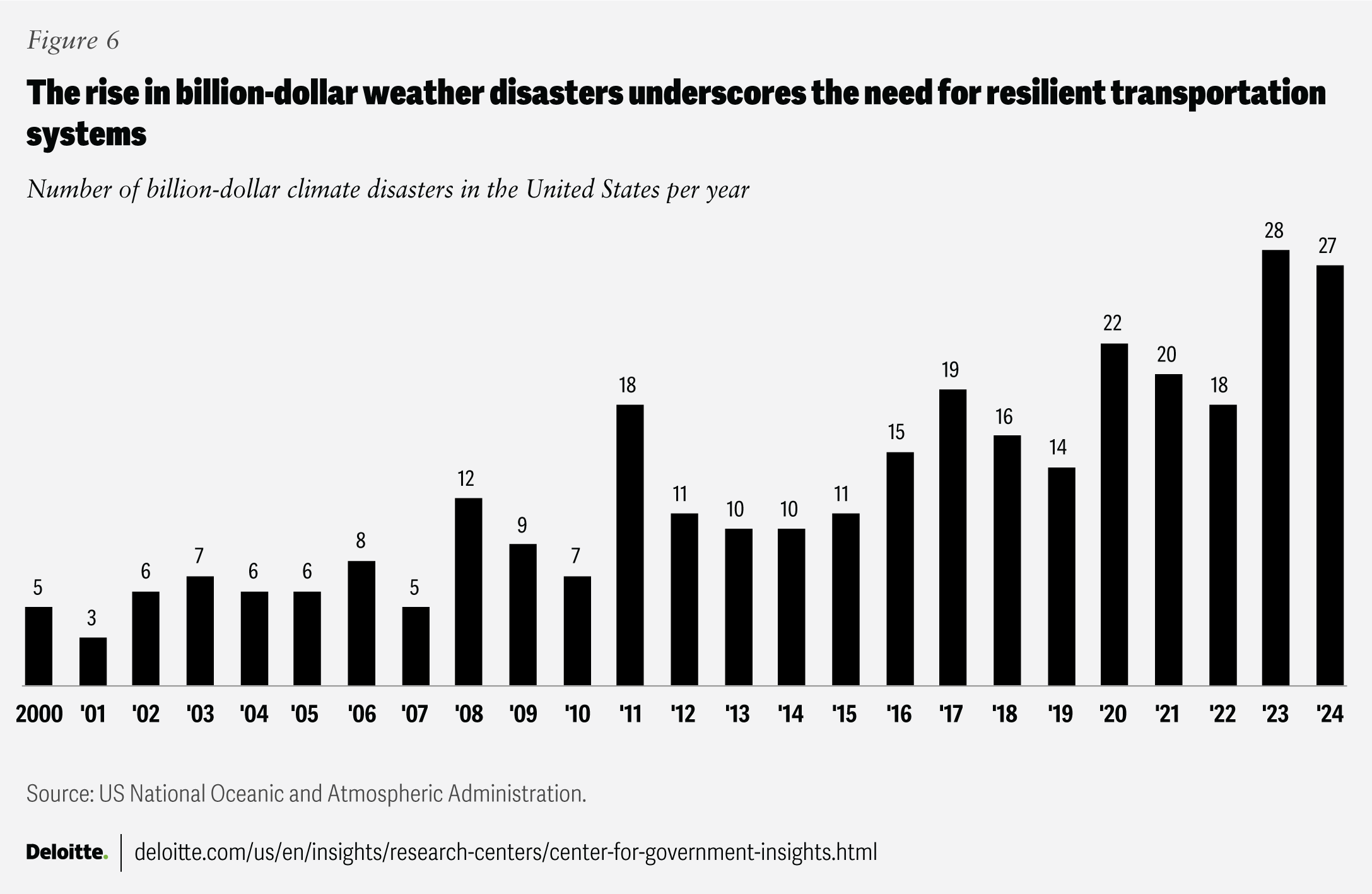

In 2024 alone, the United States endured 27 extreme weather disasters, each costing at least US$1 billion and collectively leading to the loss of at least 568 human lives (figure 6).122

Extreme weather events can affect transportation in both urban and rural areas, but rural areas typically have fewer options and resources. A damaged road or bridge, for instance, can cut rural residents off from access to food and medicine for extended periods. According to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, the average detour required by a closed or posted (with weight or speed restrictions) bridge is 1.7 times longer in rural areas than in urban areas.123

In November 2024, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and DOT signed an agreement that will give transportation officials access to environmental data and technical assistance. This initiative aims to integrate resilience into decisions on infrastructure planning, design, construction, operations, maintenance, preservation, and emergency recovery.124 These efforts can help agencies address issues such as rising salinity’s impact on bridges and culverts, changing metallurgical requirements for structures, and materials that should be used for coastal roads increasingly subject to flooding.125

Tapping into research and innovation in construction and material science

Innovations in construction and material science can help address the challenges of aging infrastructure, changing weather patterns, and increasing urbanization. Composite materials, which blend different substances to create products with new and enhanced properties, are often stronger and lighter than traditional options, and typically more resistant to environmental stressors such as corrosion and extreme weather conditions.126

Similarly, advanced manufacturing techniques such as 3D printing allow for the rapid and cost-effective production of complex structures, reducing construction time and waste.127 The use of 3D-printed components in infrastructure can be particularly beneficial in areas prone to natural disasters, as it can enable the quick replacement of damaged parts and the construction of new, more resilient structures.128

The University of Maine Advanced Structures and Composites Center, for instance, has developed new technologies, including the Composite Arch Bridge System (or the “Bridge in a Backpack”), 3D-printed breakwaters and culvert diffusers, and composite girders that can last more than a century with little maintenance.129 These innovations are designed to enhance the durability and resilience of transportation infrastructure, allowing it to better withstand environmental stressors and reduce maintenance costs.

Using digital technologies to improve transportation planning and execution

Embedded devices and sensor networks across transportation infrastructure can provide a continuous stream of real-time data for monitoring structural and environmental conditions. Michigan’s Weather Responsive Traffic Management system reduced traveler delay costs by 25% to 67% during National Weather Service advisories and warnings. This was achieved by providing automated weather alerts to motorists and aiding agency response actions in routes where mobility would be affected.130

Drones and robotic inspection technologies can enhance the efficiency and speed of infrastructure assessments, providing detailed visual and sensor-based inspections.

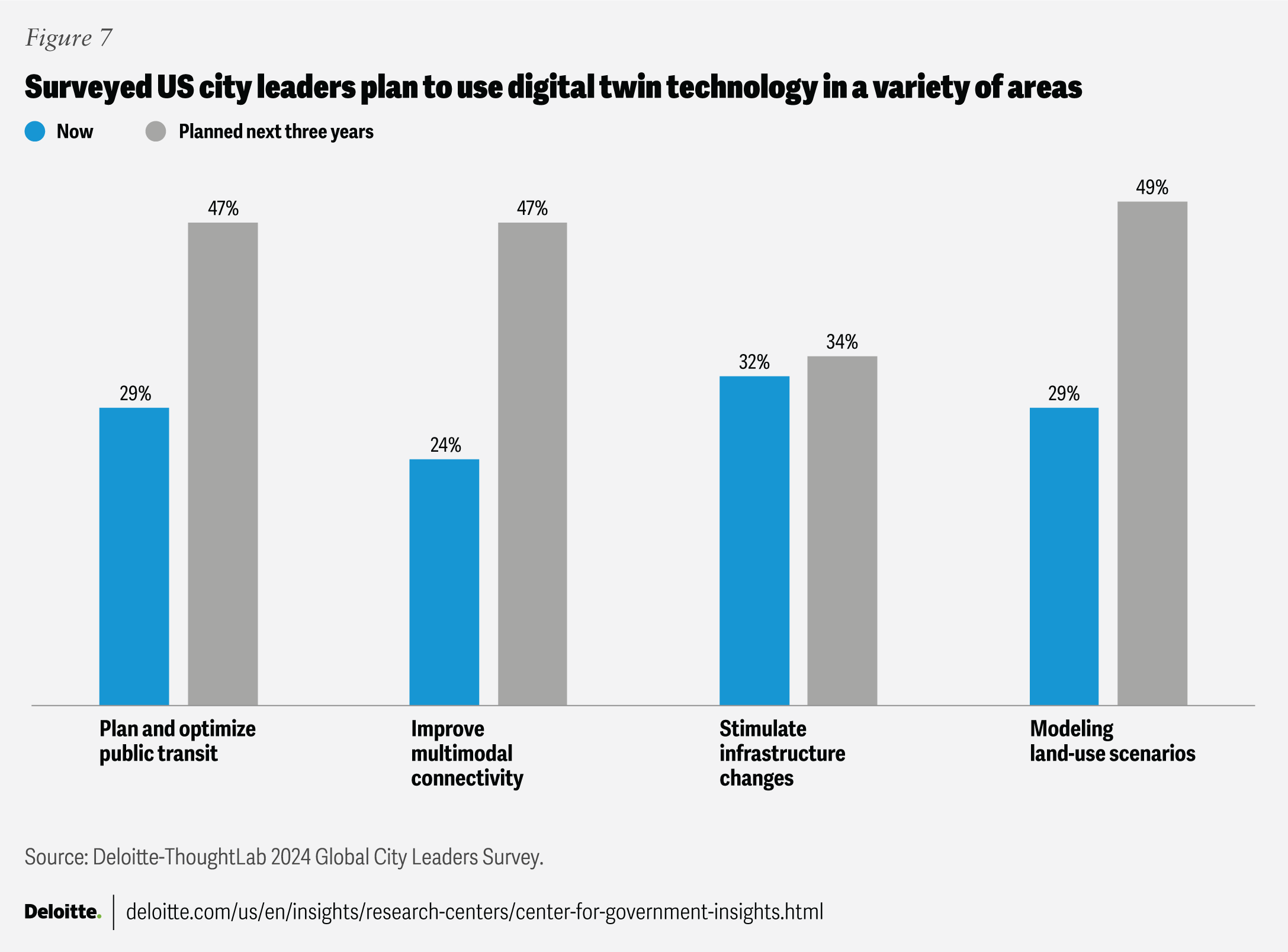

Transportation agencies are also experimenting with “digital twins” that can simulate various scenarios from routine maintenance to extreme events, helping agencies optimize their performance and resilience. A Deloitte-ThoughtLab survey of global city leaders points toward the growing use of digital twin technology in transportation and urban planning in US cities, to optimize public transit, improve connectivity, simulate infrastructure changes, and model land use (figure 7).131

Case study: Improving infrastructure delivery with digital processes and methods

The Utah Department of Transportation (UDOT) is modernizing its business systems to better serve the state’s future infrastructure needs. To achieve this, UDOT is replacing several legacy systems with integrated, cloud-based software solutions to increase efficiency and functionality. By establishing an enterprise data backbone driven by AI, UDOT aims to gain critical insights needed to effectively manage capital planning, project management, rights of way, and contracting.132

As part of this effort, UDOT is reorganizing and standardizing data across multiple processes to enable project updates and records to be more accurate, accessible, and consistent. This approach supports UDOT’s Digital Delivery model, which delivers survey, field, and design data in user-friendly digital formats. By modernizing design, inspection, and construction workflows, the agency reduces reliance on paper and improves accuracy through interactive digital models.133

Centralizing data can also remove inefficiencies that once required redundant surveys, allowing future projects to build on existing models. With the ongoing transformation, UDOT will likely be able to develop advanced digital capabilities, such as digital twin models, and enhance decision-making across all stages of infrastructure projects. Although it’s early in the process, UDOT recognizes the need for workforce training to fully adopt these new digital tools.134

Looking ahead

The journey toward reliable, safe, and resilient mobility will likely be influenced by both public sector leadership and technological developments. The five trends mentioned in this report are deeply interconnected rather than separate endeavors. When woven together, these approaches could have multiplier effects: creating sustainable revenue streams to support modernization; applying digital intelligence to optimize asset capacity; and developing secure and resilient infrastructure to mitigate the risks associated with aging systems, thereby impacting public trust and economic performance.

By combining bold investments with disciplined delivery, transportation agencies may be able to leave behind a legacy defined by improved efficiency along with safer and better-prepared networks. Success may be measured not only by the kilometers of new roads or vehicles deployed, but also by the resilience of the infrastructure, safety of passengers, and opportunities created for communities and businesses.