Making health messages matter: Reaching Americans amid information overload

What 1,500 Americans told us about trust, clarity, and health decisions

Grant McLaughlin

Alison Muckle Egizi

Anna Margaret Clyburn

Ipshita Sinha

Nicole Savia Luis

Americans are likely to scroll past thousands of digital messages every day. Health advice from doctors, headlines about a recent study, a friend’s post about a miracle cure, an influencer’s wellness tip—all can blur together in an endless digital stream.

Yet when it comes to their health, Americans report they want reliable information they feel they can trust and understand. But there’s one problem? No matter the channel, the loudest voices aren’t always the most credible ones.1

The numbers help tell the story: Americans spend over six hours daily consuming digital content, while brands spend US$259 billion annually competing for their attention.2 In this noisy landscape, health messages from health agencies often get drowned out. Harvard University found that a typical state health department X post between 2012 and 2022 generated just two “likes” and a single retweet, and 1 in 8 posts attracted no engagement at all.3 In 2017, a University of Iowa study found that fewer than 5% of federal health agency social media posts receive more than 100 shares, “likes,” or comments.4 Meanwhile, health claims from social media influencers have raced through the feeds of audiences, numbering in the hundreds of millions.5

Americans encounter health information from a wide array of sources, and the information isn’t always reliable. This can create a dangerous gap: Americans might make health decisions based on false, inaccurate, or misleading information rather than science, and could potentially see worse health outcomes as a result. For instance, one study found that reliance on internet sources rather than health care providers for breast cancer information correlated with reduced mammography screenings.6

But there’s hope. When health agencies use effective messaging, they can break through the noise and help Americans make informed decisions about their health. The US Consumer Product Safety Commission frequently garners upwards of multiple thousands of engagements per X post using memes and parody-style characters to share safety reminders about things like beach umbrella injuries, signifying that government agencies can succeed in the digital space.7 The question is: How?

Methods

This article explores how health agencies can help deliver on Americans’ desires for health information in the online environment. Through a nationally representative survey of 1,500 American adults in June 2024, Deloitte Center for Government Insights investigated Americans’ health communication preferences. To supplement survey findings, the center conducted a review of health communication literature and synthesized semi-structured interviews with health leaders across government, academia, and the private sector. The center synthesized insights to identify potential paths forward for strengthening health communication in the digital age.

Our survey points to Americans’ preferences for consuming health information

Given the vast amount of health information available, understanding Americans’ preferences for consuming health information is important. Our survey adds new evidence to the existing literature and suggests: 1) Americans face a dizzying array of health information and want help to navigate it; and 2) they seek reliable, digestible, and transparent health information to help them cut through the noise.

The proliferation of health information can confuse Americans, and many want help navigating it

Health information reaches Americans through a crowded and often inconsistent landscape.8 Americans can encounter health messages from medical professionals, non-credentialed social media influencers, the media, friends, and family, both in person and via digital or social platforms, often all within the same day. While this level of exposure has the potential to create an informed public, it can lead to confusion.

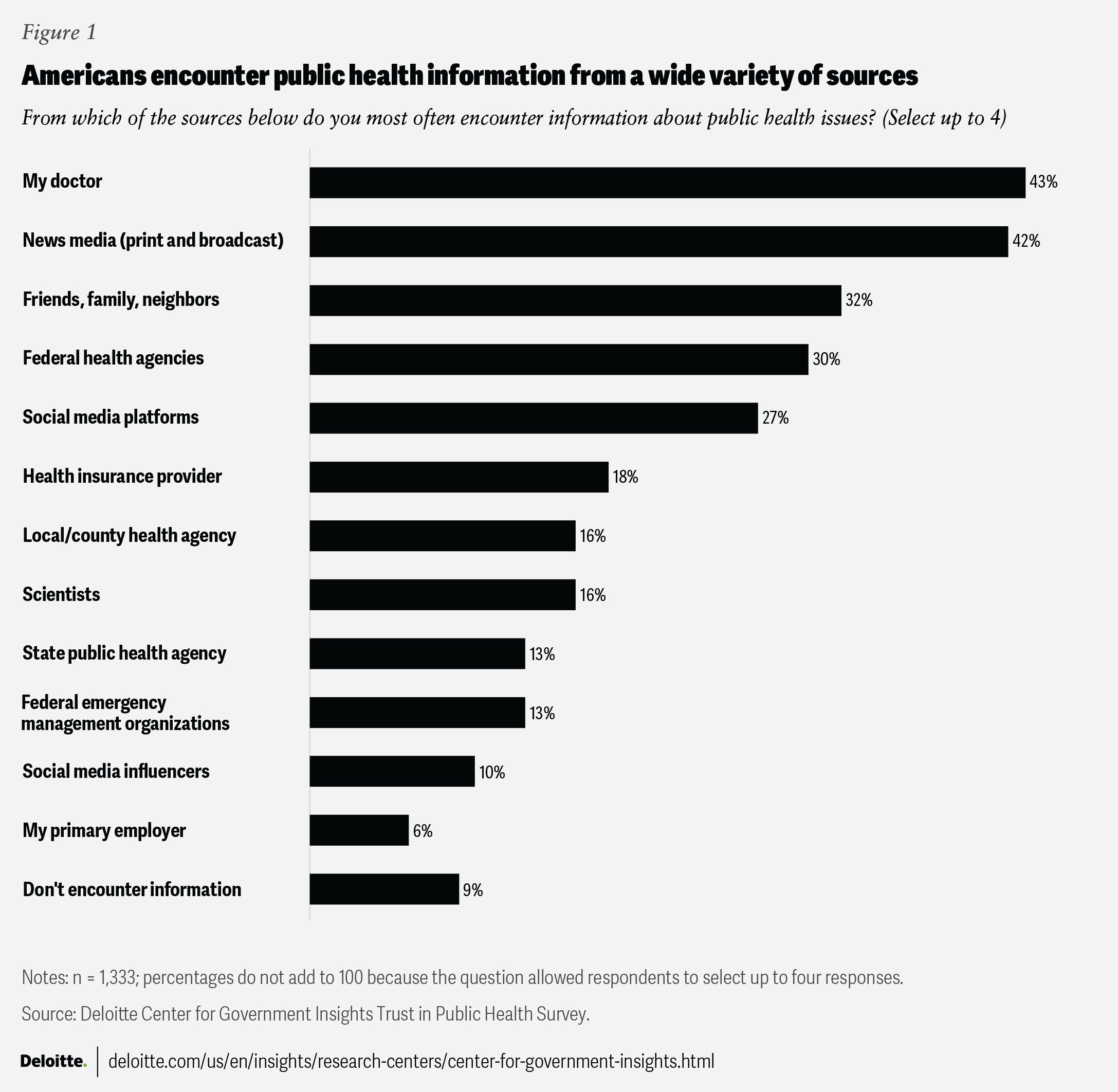

According to our survey, 4 in 10 respondents reported encountering public health information most often from 1) their doctors, or 2) broadcast or print news media (such as national and local television news stations, newspapers, and magazines, both print and their websites). Roughly 3 in 10 respondents reported encountering public health information from personal networks like friends, family, or neighbors; federal health agencies; or social media.

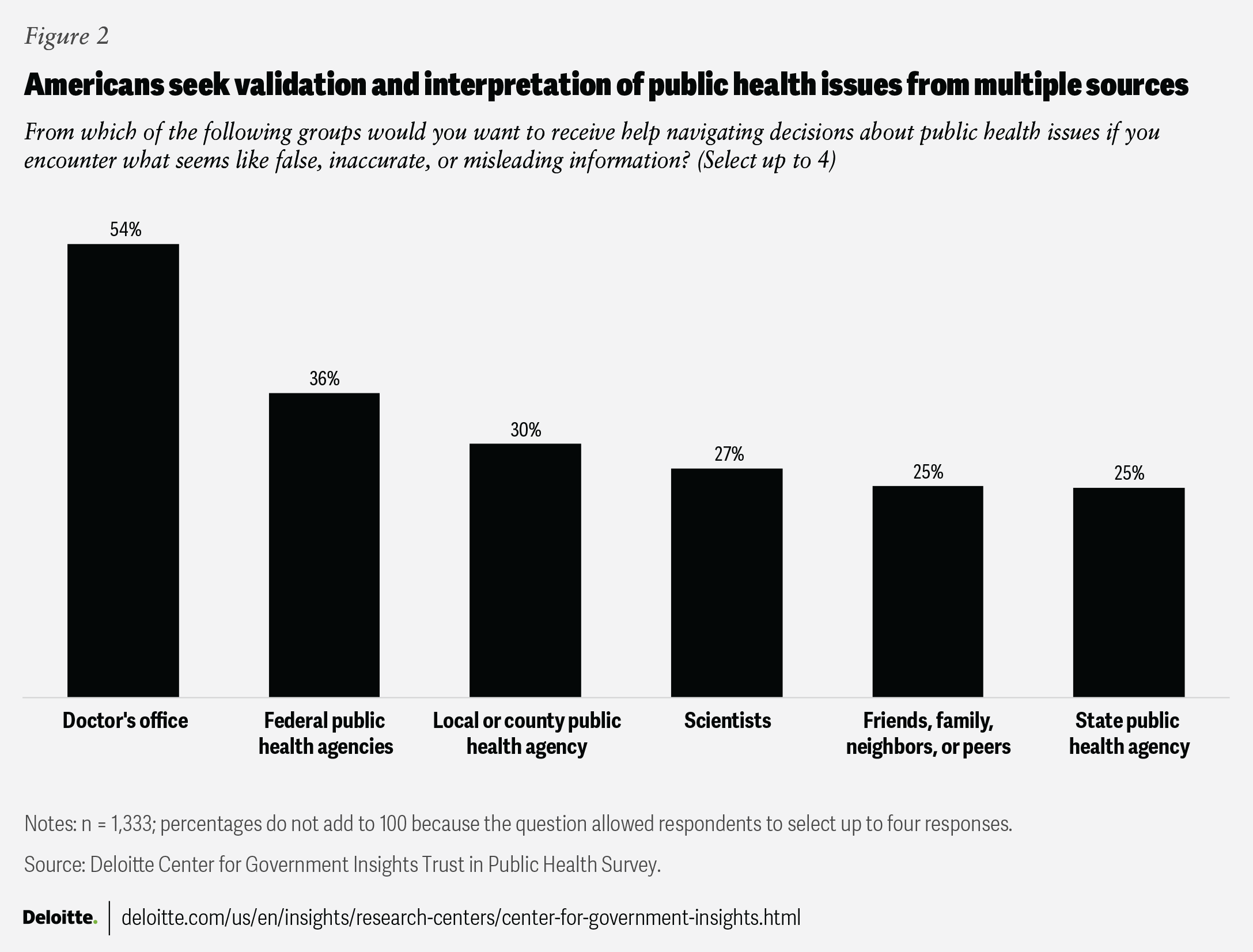

Americans do not appear to be passive receivers of this information and express a desire for support in making sense of it. This is particularly true when they suspect that what they’ve heard or read might be false, inaccurate, or misleading information. According to our survey, doctors were the most preferred source of support (54%) for navigating health decisions when faced with what they perceive to be false, inaccurate, or misleading information, followed by federal public health agencies (36%); local or county public health departments (30%); scientists (27%); and friends, family, neighbors, or peers (25%). This could suggest that while information comes from a wide range of sources, Americans continue to seek validation and interpretation from multiple sources they believe to be authoritative and credible.

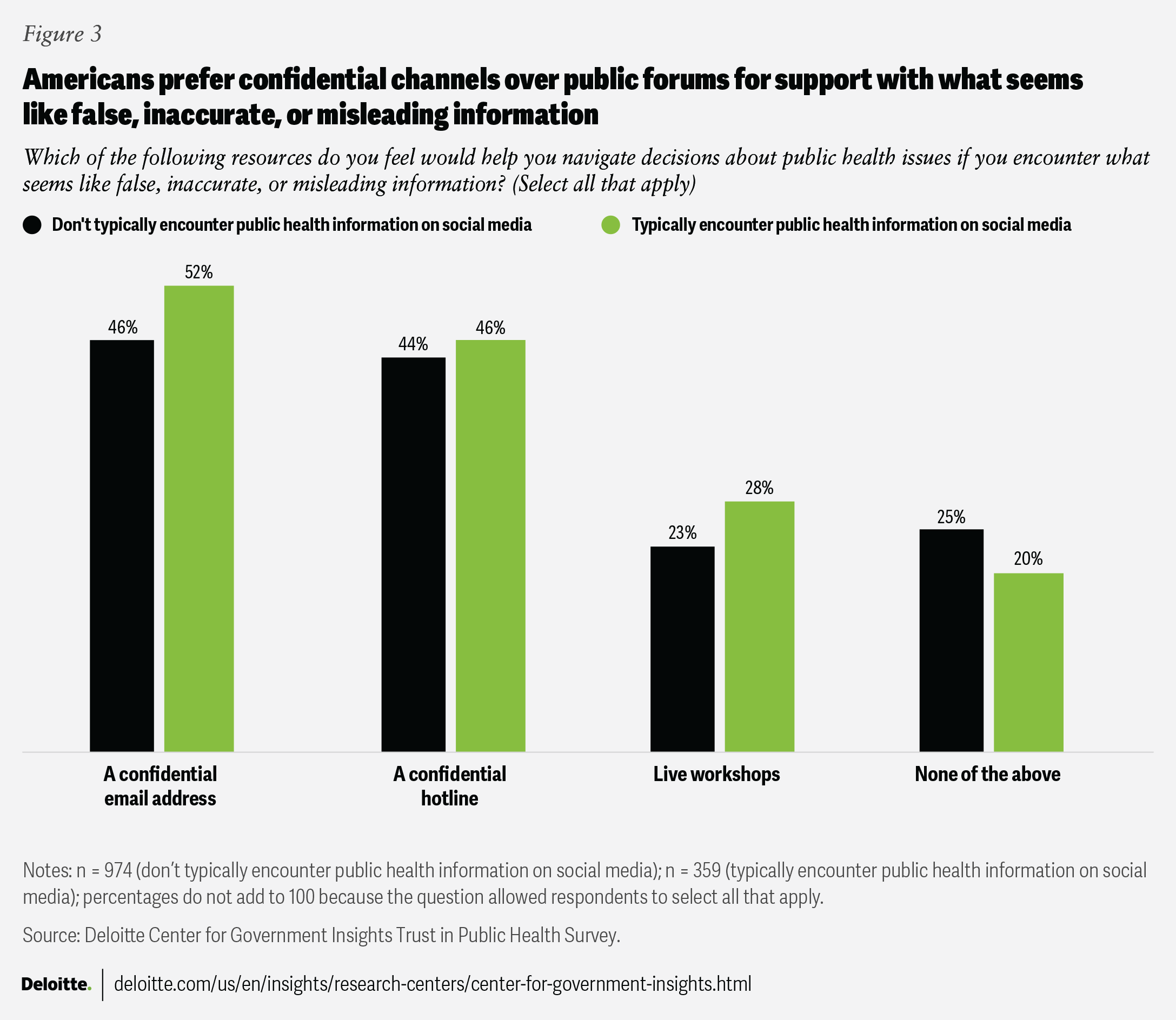

When asked what resources would be most helpful, respondents who used social media as a primary information source were more likely to want a confidential email address from sources they trust where they could ask questions anonymously to help navigate health decisions (52%) compared to those who don’t use social media as a primary information source (46%). Disinterest in any resources to help navigate false, inaccurate, or misleading information was higher in those who don’t typically use social media for public health information (25%) compared to those who typically use social media (20%).

Reliable, digestible health information is key to meeting the needs of audiences

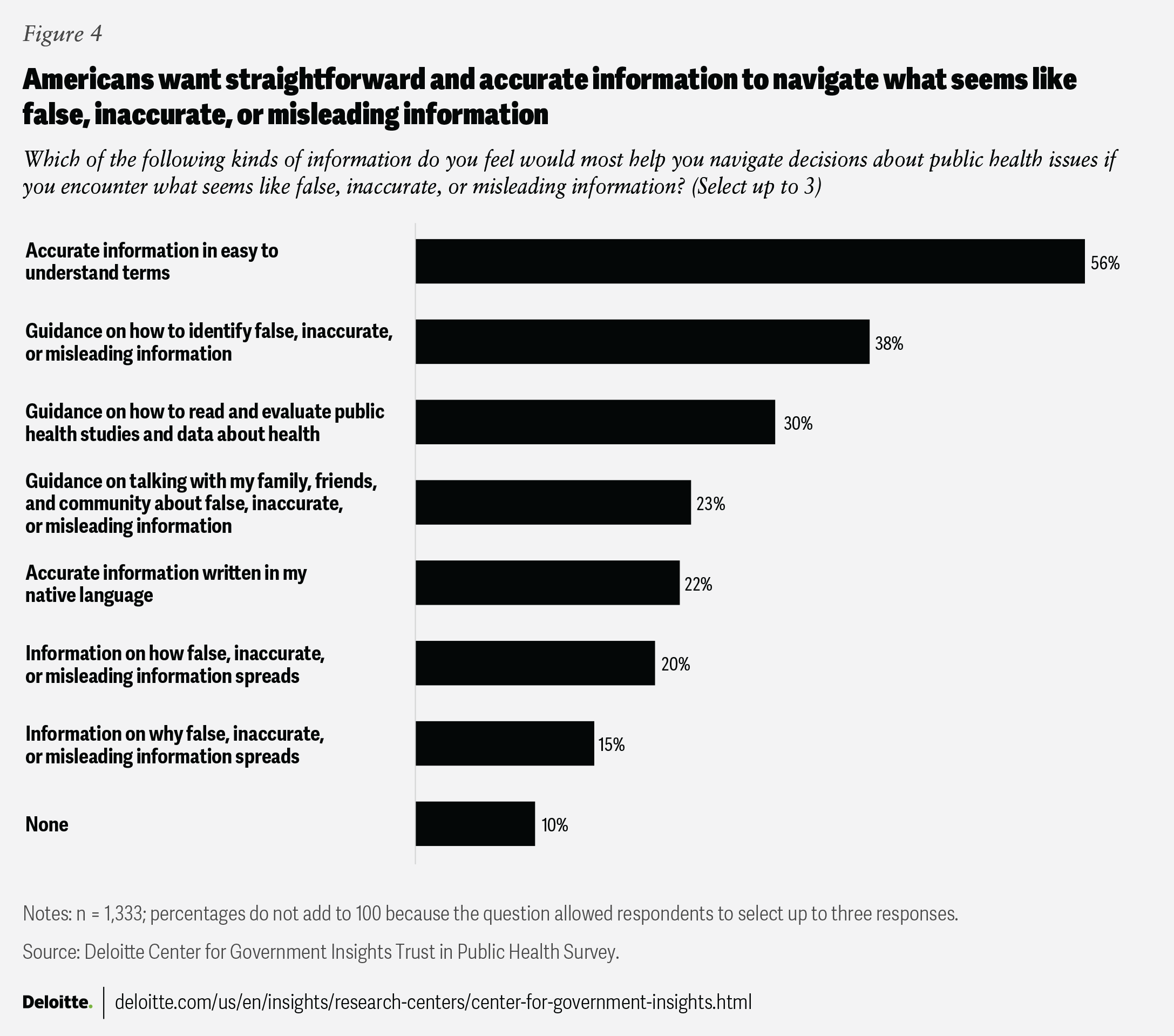

Factual and easily understandable health information matters when it comes to health decision-making. Our survey reveals that more than half of all respondents consider accurate information in easy-to-understand terms valuable when faced with claims that seem false, inaccurate, or misleading. Moreover, 38% of respondents expressed a need for guidance in identifying false, inaccurate, or misleading health information, and 30% sought support to interpret and evaluate health studies and scientific data. This seems to underscore the importance of translating evidence into plain language, clear comparison scales, and visual depictions. These findings point to a practical request for strategies that empower Americans to critically assess health-related claims and make informed choices.

Americans also appear to value transparency in health communication, and their trust in agencies may be linked to perceptions of transparency. Our survey found that 3 of the 4 top reasons for low trust in public health agencies were related to a desire for transparent communication, with 48% reporting low trust due to agencies not sharing information, reasons for decisions, or choices in straightforward or plain language.

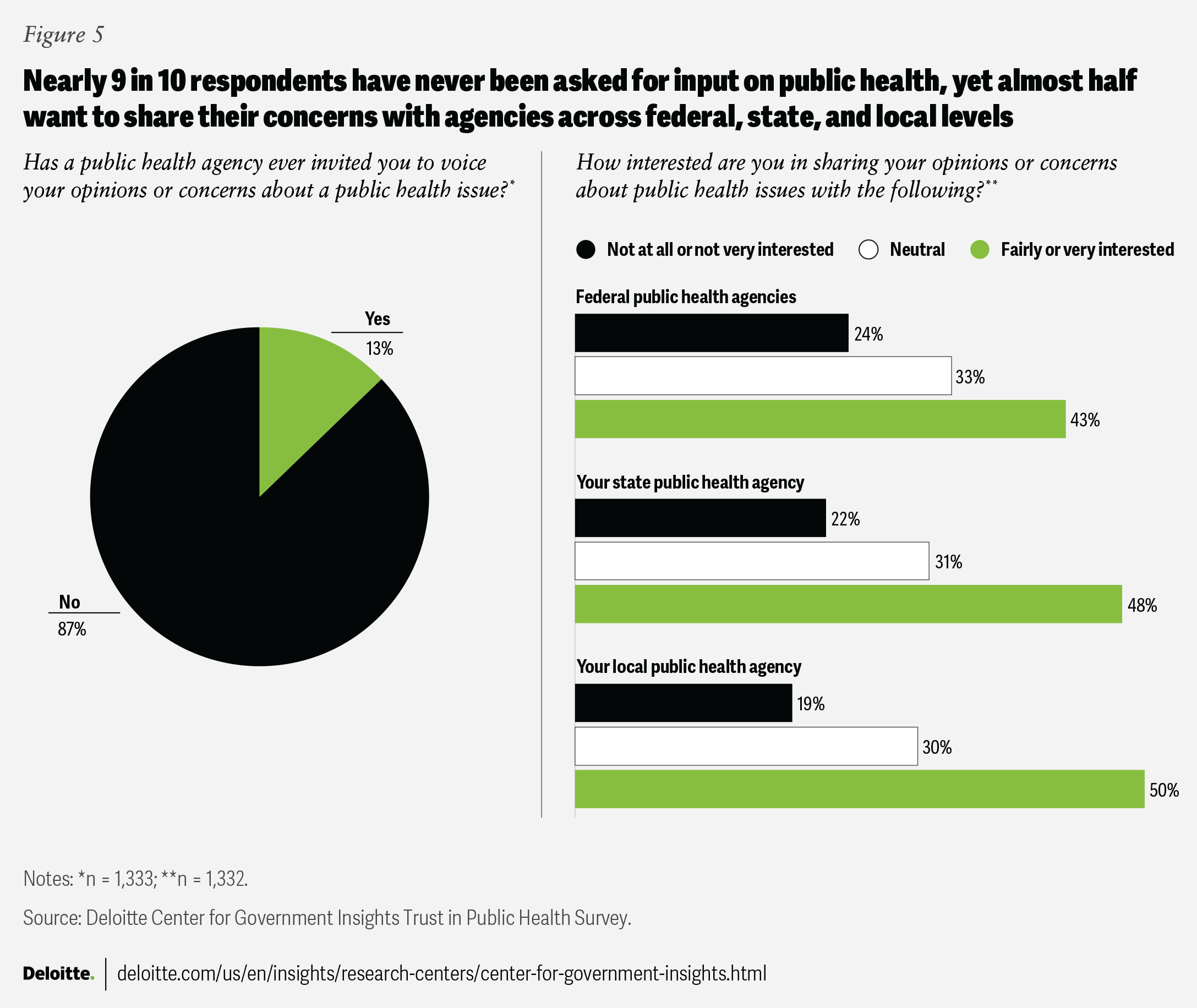

Respondents also prioritize more communication avenues with health agencies. Nearly 9 in 10 respondents (87%) reported never having been invited by a health agency to voice opinions or concerns about a public health issue. But almost half of the respondents reported wanting the opportunity to share their views with federal, state, and local health agencies. Such engagement could include participating in community forums, responding to public health surveys, joining advisory panels, or attending virtual town hall meetings hosted by health officials.

Ways to consider getting Americans the health information they need, when they need it

Americans are awash in health information, yet our survey shows they still want help making sense of it. All the data from our survey points to the imperative: meet people where they already are, in plain language, through voices they trust, while keeping every channel on the same evidence-based page. That means pairing social media posts with community flyers, local radio spots, and trusted in-person forums in areas without digital access. The five moves that follow can turn this guidance into practical next steps agencies can start on right away, so Americans can get the health information they need, when they need it.

1. Empower unconventional messengers to deliver the right information

A leading epidemiologist might have 30 years of experience and a wall full of degrees. A 19-year-old social media influencer could have two million followers and a ring light (a circular light that improves one’s appearance on video). Guess who’s more likely to convince teenagers to get off the couch and go for a walk?9

While it’s important that accurate health information comes from qualified specialists, collaborating with messengers Americans already look to for information, like influencers, can help amplify those messages and encourage healthy behaviors.

Researchers generally agree that selecting trustworthy, relatable spokespersons is crucial for improving the public’s engagement with and response to health information.10 Our survey shows Americans look to both institutional and personal trusted sources to help untangle questionable public health claims. Over half of respondents look to doctors for input, a third report going to federal or local health agencies, and a quarter seek support from social media sources. In practice, people piece together guidance from many places, not just the exam room. Physicians, public health officials, and content creators can all be vital contributors to bettering Americans’ health.

Strategic vetting can help when choosing spokespersons. Selecting an appropriate spokesperson can be tricky. It’s not just about finding someone persuasive. It’s also about managing reputational risk. A spokesperson might align perfectly on one issue, while simultaneously holding or sharing opinions that are factually problematic on other issues. That tension doesn’t mean spokespersons aren’t worth the investment, but it does call for careful vetting, clear messaging agreements, and preparation. Media training, scoped collaborations, and values alignment can reduce the chance of a single off-message comment backfiring on the agency.

Real people’s stories speak for themselves. When the audience can see themselves in authentic, relatable messengers, the messages are more likely to stick. As one former state health commissioner shared, “people need to see a face behind public health that’s in their own community.”11 The smoking cessation campaign of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Tips from Former Smokers (Tips) featured compelling stories of people who suffered immensely from the toll of smoking-related conditions such as cancer, gum and heart diseases, and even amputations,12 highlighting the lifelong illnesses they now endure and the struggles of loved ones who now care for them as they deal with the lasting health challenges.13 One evaluation estimated that the Tips campaign produced 16.4 million quit attempts and 1,005,419 sustained quits.14

Similarly, the Truth Initiative, a widely recognized teen smoking prevention and cessation effort led by the nonprofit American Legacy Foundation, selected young Americans with opioid use disorders as spokespersons for their The Truth About Opioids campaign. With the slogan, “Know the truth, spread the truth,” the campaign encouraged young people who saw the campaign to share their experiences with their personal networks. From 2018 to 2020, the campaign reduced the percentage of young people who agreed with the statement “If I got a prescription opioid from a doctor, I would share some with my friends” by 27%, increased the percentage of young people who agreed opioid dependence can occur in just five days by 46%, and increased the likelihood that young people would search for the terms “opioid epidemic” and the campaign’s slogan “know the truth” by 600%.15

Clinicians on social media can play a hybrid role: professional and relatable messengers. Doctors, nurses, and clinicians with a public social media presence can serve as effective spokespersons. Using personal stories, clear visuals, and accessible language, they can translate relevant but complicated health information into something approachable and actionable. Agencies can support these figures with resources, verified content, and reposting collaborations. This model can blend clinical authority with everyday relatability, expanding reach without sacrificing rigor.

2. Empower trust networks to carry the message

You can’t be everywhere, but your message can. Picture this: It’s 6 pm on a Tuesday. Somewhere in America, a worried parent is putting “eating disorder” in their internet search engine, while their teenager argues fasting is healthy and everyone at school does it. Meanwhile, a grandmother is sharing a social media post about miracle cures, and a college student is asking friends if that health headline is real. You can’t be in every conversation to check whether reliable information is being shared. But trustworthy information can be within reach in all these scenarios.

That’s why agencies should consider using trust networks: a complex, distributed web of community-anchored messengers who already command credibility in their circles, from barbers and faith leaders to local librarians and parent-teacher volunteers.16 These are not formal spokespeople. They’re not making public service announcements or appearing in national campaigns. But they may be the first person someone turns to for health advice. That makes them important.

Build trust networks that can extend the reach of health communication. Our survey demonstrates that Americans seek information on public health from a wide variety of sources, all of which can serve as potential health messengers in the trust network.17 Health agencies can begin by assessing the capabilities of key stakeholders, including community members themselves.18 Potential collaborators can be hiding in plain sight, so building trusted networks takes proactive effort. Agencies need to take every opportunity to identify engagement prospects and grow relationships, whether at community events, conferences, or by scanning social media posts.19 And since Americans sometimes look to personal relationships when information feels shaky, such networks (librarians, coaches, barbers, peers) can fill that role, especially if agencies support them with a consistent set of reliable information.

Beyond relaying trusted messages, these networks might be able to fill roles that health agencies can’t. Agencies cannot be everywhere all at once, simultaneously replying to concerned social media posts and answering questions at the dinner table about an emerging public health threat. Though trust networks may not always extend to the dinner table, they can include community members Americans interact with every day. A network of trusted collaborators can extend the reach of agency communication.20

Over time, with agency commitment and resources dedicated to collaboration and a flexible approach to meet the needs of all involved, trust networks can support stronger health messaging. To maintain stakeholder involvement in trust networks, agencies can also incentivize these networks to collaborate through various mechanisms, including providing access to funding or facilitating referrals to funders where feasible. Trust networks can be motivated to participate with nonfinancial resources too, like supporting an organization’s workforce development, initiating community events, providing technical assistance, and linking stakeholders to services within the network.21

Working with trust networks involves letting go of full control over the messaging. Sometimes, this process can shift ownership of health messages outside of health agencies, which can feel uncomfortable.22 Offering reliable information and guidance for trust network messages can help improve messaging consistency. And there’s a potential bonus in time saved, too: When the messages are crafted by secondary messengers themselves, it can ease the message approval process, making governments more agile and likely more effective in communicating important messages.23 With real-time posting, agencies can also swiftly remove posts in case of errors.

Health agencies can also use a tool called the unmet desire survey to help agency staff acknowledge and face their concerns about messaging collaboration. The survey asks about staff challenges and attitudes toward collaboration, which can, in turn, help leaders understand what needs can be met through collaboration and what concerns should be addressed before successful collaborations can be built.24

Trust networks can share community concerns and needs with health agencies. A decades-long collaboration between the University of Maryland School of Public Health and local barbershops helped improve responses to erroneous information. One of the barbers, a community health worker, found a flyer with inaccurate health information and brought the flyer to the University of Maryland.25 This act of shared responsibility and trust paved the way for a series of ongoing conversations, like townhalls that brought together scientists, policymakers, and community members, including barbers and others, each having an equal voice, to discuss health needs and concerns in the community.26

Trust networks can also serve to shore up trust in public health authorities. In Flint, Michigan, residents were uncertain whether they could trust certain health information. To overcome this challenge, one community-based organization created a public-private collaboration formed of academics, the health department, grassroots organizers, and community- and faith-based organizations. The group worked together to craft accurate, accessible, relatable messages that were often delivered in person by task force members to the community. As a result, community members felt more confident following guidance after hearing messengers they trusted relay vetted information consistent with national public health messaging.27

3. Write like people’s lives depend on it, because they might

Every day, Americans likely scroll past health advice that could save their lives. Why? One reason might be that brands spend US$259 billion annually to capture attention.28 In contrast, health messages can read like instruction manuals written by robots.

Our survey reveals what Americans appear to want most from health communicators: accurate information in plain terms. And that’s not always easy. Public health communication at times operates in an environment where science can shift rapidly, guidance may need to change as new data emerges and research on the best approaches to disease prevention and treatment makes strides each day. Moreover, public health leaders don’t typically have training in communication. But these challenges can also result in opportunities. With each piece of information that has undergone rigorous review and is ready to be communicated to the public, especially during ambiguous times, there’s an opportunity for health leaders to reinforce credibility and earn the public’s trust.

Transparent and accurate communication doesn’t necessarily mean releasing all of the information and facts all at once. Rigorous review can be time-consuming. But if public health leaders end up releasing either protected or inaccurate information, they may risk losing public confidence and could make Americans less likely to trust or act on any future guidance. Across both routine and crisis communication, two principles consistently stand out as integral: 1) trust and 2) accuracy. 29 These should help guide health messaging, regardless of the situation or the speed at which information is evolving.

Once public health leaders have the facts in place, the next major step is to craft a message the public can easily understand and act on. To maintain the trust of both public and private stakeholders, health leaders can tell people what they need to hear, even when it may not be what they want to hear.

Two toolkits health communicators might find resourceful

Before you write your next health message, ask yourself: Will this pass the “kitchen table test”? Can someone explain this to their family over dinner without confusion? Striving for this level of clarity can help health messages be better understood. But it can be a difficult goal to achieve. Here are a couple of available resources that could help.

Toolkit 1: Public Health Communication Collaborative toolkit30 offers four practical recommendations for audience-centered writing.

- Jargon check: Could a middle schooler understand this?

- Sentence check: Are most sentences under 20 words?

- Voice check: Am I talking to people, not at them?

- Scan check: Can someone get the key points in 10 seconds?

Toolkit 2: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication toolkit31 focuses on high-pressure situations. When a crisis hits, people aren’t thinking clearly. Your message needs to work for people navigating that uncertainty, often with fear and anxiety.

- Make it memorable: “Stop, drop, and roll” beats a paragraph about fire safety.

- Give clear next steps: “Call this number” is more specific than “Seek appropriate medical attention.”

- Validate feelings: “It’s normal to feel worried” goes a long way.

- Provide options: “You can do X or Y” feels less controlling than “You must do X.”

- Test your message: Read it out loud. If you stumble, your audience will too.

These toolkits can mean the difference between messages that get ignored and messages that can save lives.

Crafting public health messages that are transparent, accurate, and easy to follow may involve rethinking the process by which public health communication is developed.

Consider skipping sequential message review and gathering for an all-stakeholder review. Traditionally, some public health agencies rely on a sequential review process where messages pass through multiple layers of feedback before dissemination.32 Although this method is intended to produce greater accuracy and thoroughness while mitigating risk, it can hamper clarity and speed. More reviewers may not always equal better messaging.33 During a food safety incident in 2009, a draft press release about a pistachio recall was passed from one Food and Drug Administration reviewer to the next over four hours, with each adding input, like a game of telephone. The result was an unclear, confusing message. Since then, this team moved to a simultaneous message review process, gathering all the necessary message reviewers in the same room to finalize communication in real time.34

Effective digital communication goes beyond words on the screen. In addition to working to make public health messages clear and accessible, agencies should also consider how to design content to be more engaging, particularly on social media, where a strong competition for attention tends to exist. Visual design choices such as bright colors, positive images, text that’s easy to read, and relatable images of people and places can all boost social media engagement metrics such as the number of likes, comments, and shares the messaging receives.35

Health agencies can also tailor content to fit how Americans use each social media platform, which can help improve visibility. This includes using hashtags to join broader conversations and amplify reach, improving content with the addition of interactive elements such as polls, and even tapping into popular visual or audio trends, such as reels, to boost algorithmic reach. Developing a consistent persona or voice for the spokesperson can also help capture and maintain audience attention.36 But it is important that the spokesperson’s voice comes across as authentic to help earn trust and respect.

Timing can be everything. In addition to platform-specific tailoring, the time when information is released and updated can determine the reach of messages. Content shared when most individuals are offline may get relegated to the bottom of social media feeds. And outdated messages can add to the already-busy online information environment. An exposure strategy can help health agencies decide who sees each message, how often, and for how long. Frequent releases and click-through links to regularly updated information can also help agencies keep communication fresh and relevant.37

Agencies may be able to draw in social media audiences by “keeping it real.” Public health leaders can look for inspiration in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History’s approachable communication style. The museum tapped into the public’s fascination with dinosaurs to spark new interest in science, especially among younger audiences. In 2019, through a six-month social media campaign leading up to the opening of its renovated fossil hall, the museum balanced crowd-pleasing content such as dinosaur face-offs with authentic, behind-the-scenes stories of the scientists behind the research. Humanizing researchers and making science more relatable helped cultivate meaningful connections. The campaign generated 1.1 million engagements across 892 posts and more than 7,600 uses of their #DeepTime hashtag during the two-week finale, demonstrating how blending science with storytelling can help inspire curiosity and grow community.38

4. Avoid telling people what to do. Help them choose.

Dartmouth researchers discovered something that might concern most health communicators: Giving people scary health facts makes them less likely to change their behavior.39 The better play might be to supply clear information and options and let the audience decide what’s right for them.

Health authorities can craft autonomy-enhancing messages that empower Americans to make healthier choices.40 The Truth Initiative encourages adolescents to challenge the messages of tobacco companies vying for their attention and dollars with edgy campaigns that emphasize teens’ agency in their own health choices. With mental health being a rising challenge for adolescents, in 2021, Truth launched a campaign called It’s Messing With Our Heads, highlighting how many teens turn to vaping to cope with stress, only to find it can worsen anxiety and depression. One ad series follows a salesperson for a fake vaping company, Depression Stick!, as he unsuccessfully tries to sell the vaping products at a gas station by marketing them as “amplifying feelings of depression and anxiety” and “making depression convenient.”41

The campaign reached teens where they are with social media takeovers, influencer unboxings of the fake vape product, highly visible billboards, branded pop-up shops, and even Sunday night football ads, achieving between 50% and 78% awareness week to week.42 The results demonstrated reduced odds of intent to use and current use of e-cigarettes, with 14% to 18% reduced e-cigarette use among teens during weeks when campaign awareness reached 65%.43 Using data from the US Census Bureau, Truth estimates it likely prevented 1.5 million youth between 15 and 24 years old from initiating vaping between September 2021 and October 2022.44

The Hear Her campaign in 2020, launched by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and collaborators, also leveraged autonomy-enhancing messages to raise awareness of urgent maternal health warning signs.45 By equipping expectant women—as well as their families, friends, and health care providers—with practical tools like a warning sign checklist, self-quizzes, and conversation guides, the campaign sought to empower women to trust their instincts, advocate for their needs, and actively participate in decisions about their care. With taglines like “Hear her concerns” and “You know your body best. If something doesn’t feel right, say something,” the campaign encouraged women to speak up for their health while reinforcing autonomy by affirming their experiences and supporting informed decision-making.46

Likewise, smoking cessation decision aids can give patients a greater sense of agency in health decision-making and strengthen their role as active participants in their own care. In one study, patients who used these aids and consulted with physicians reported higher confidence and readiness to quit compared to those who didn’t.47 Many reported that they felt more prepared to make decisions about quitting and expressed satisfaction with both the decision aid and their clinician.48

5. Turn broadcasters into conversation starters

During a workshop hosted by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine in March 2023, Itzhak Yanovitzky, professor of communication and public health at Rutgers University, remarked, “Sometimes we think we have a communication problem, but we have a relationship problem instead.”49 Through dialogue, health agencies can build relationships with Americans that enable timely communication on topics beyond Americans’ initial interests.

Our survey findings suggest Americans may not feel they have an opportunity to share thoughts with public health agencies, but many want to. Two-way communication can help build relationships with the public and improve the effectiveness of messaging. As one health system leader noted, “We’ve always felt you can actually get better engagement from people if their voice is heard and that there’s a much more robust relationship between public health and the population it serves.”50

Bidirectional communication has greater potential to build trust and increase messaging effectiveness than one-way messaging.51 This involves active listening, dialogue, and responsiveness over the long term. Organizing feedback sessions, providing dedicated space for responding to specific questions or concerns, or receiving feedback on communication activities can help agencies make sure that health messages resonate with different audiences.52

Building strong relationships may involve public health agencies prioritizing communication about what Americans report they care about. After relationships are formed, however, public health agencies can introduce other topics they feel require attention.53

Agencies can leverage social media to connect and engage with audiences more effectively. Some health departments already outline social media platforms as a meaningful, two-way communication channel with Americans.54 The Health Department of Kansas City, Missouri, has woven social media into its culture and strategy to engage community members, especially those who may be difficult to reach through traditional channels.55 The health department sees social media as a necessary tool to participate in the broader public conversation. Through video content, visuals, and timely messaging, the department amplifies public voices. With more accessible and relatable communication, social media can go beyond just outreach and become a channel for interaction that can increase reliability and trustworthiness.56 More can replicate these leading examples to maximize this technology’s utility for creating feedback loops with the public.

However, not every American has access to and uses social media. Agencies could also institutionalize town halls, mailed surveys, phone hotlines, and in-person connections through trust networks to gather input from groups less engaged online. These complementary offline feedback loops can make sure that every community member has a chance to weigh in.

Americans report they want to make healthy choices. Make yours the message they notice.

While you’ve been reading this article, roughly 2,000 Americans might have made a health decision based on information they found online.57

More Americans are likely being inundated with health messages from influencers. The digital noise doesn’t seem to be getting quieter; it appears to be getting louder, more sophisticated, and more persuasive.

But here’s what our survey of 1,500 Americans suggests: People want to make good health decisions. They want trustworthy information, and they’re willing to listen—if you know how to reach them, both online and offline.

Appendix: Methodology

The Deloitte Center for Government Insights conducted a mixed-methods study that included a comprehensive literature review, interviews, and an online survey of 1,500 United States adult residents conducted between June 7 and June 17, 2024. The survey sample was a YouGov panel weighted to be nationally representative of US adult residents. The margin of error for the sample was +/–2.73%. The center conducted data quality checks on respondents’ completion times and the completeness of their responses, after which 167 respondents were removed from the sample, resulting in a total of 1,333 respondents. The center also synthesized interviews with leaders across public health, health care, philanthropy, and academia to assess perspectives on the challenges and opportunities in health communication today.