Designing for disassembly: What would it take to build a sustainable car?

Circular design can help companies to cut costs, drive revenue, and achieve their carbon reduction goals. Deloitte explores what this looks like for the automotive industry.

To date, most corporate sustainability efforts have focused on sourcing renewable energy or improving energy efficiency to reduce a company’s carbon footprint.1 But energy use is just one part of the decarbonization equation.

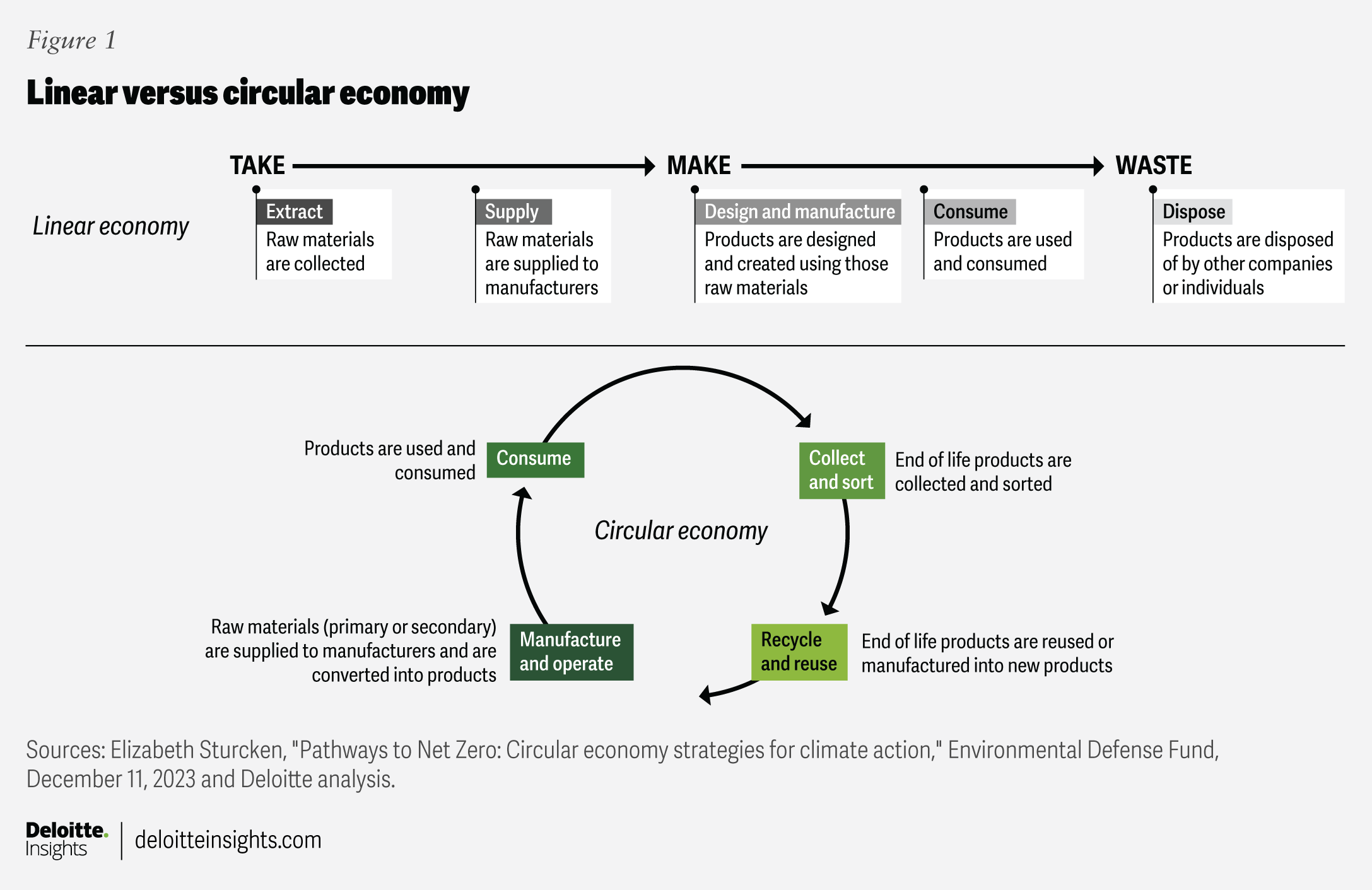

For a company to meaningfully reduce its energy use, it needs to reduce the material intensity of its products across the full value chain. Circular design can be a transformational strategy to support that goal, because it requires companies to reimagine product design, from the chemistry of the materials it uses, to how those products are manufactured, and how each component in that product is managed at the end of its life (figure 1).

Embedding “circularity” into the design and manufacturing process is no easy task, though, especially for complex consumer products like automobiles. A single car can comprise nearly 30,000 components2 such as touchscreen displays, air conditioning systems, and hybrid battery-powered engines. A circular vehicle would be one in which every component would be recovered or remade from an existing vehicle, with nothing thrown away or removed from the system.

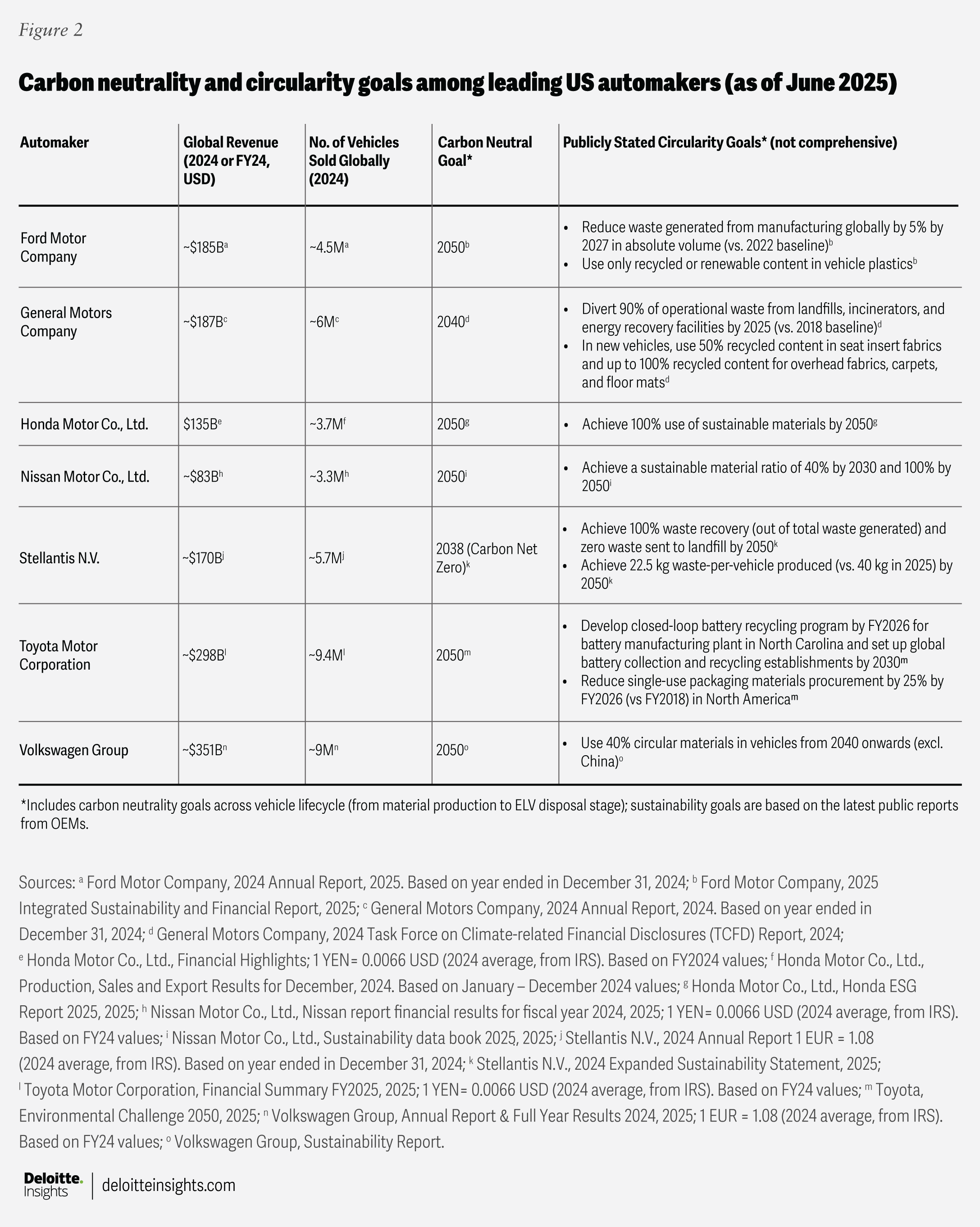

That being the case, most circularity efforts in the automotive industry so far have been limited in size and scope, but this is poised to change. Leading US automotive companies have a carbon neutrality goal, and circularity is a key strategy to achieve that ambition (figure 2).

In fact, when compared with a combustion engine vehicle, the World Economic Forum estimates that circular strategies could cut the industry’s carbon footprint by as much as 75% and reduce resource consumption by up to 80% per passenger kilometer by 2030.3

Emerging regulations in the European Union are likewise guiding companies toward circularity by requiring end-to-end product traceability. The EU Battery Passport,4 together with the European Critical Raw Materials Act,5 for example, require companies to track and disclose detailed information on material composition, sourcing, and lifecycle impacts at a far deeper level than before.

Circularity also offers a potential competitive advantage by reducing costs and improving operational efficiency. Ford, for example, is repurposing manufacturing waste such as scrap aluminum directly into products like the F-Series truck.

Consumer preferences seem to be shifting to support sustainable products, too. According to a survey of 5,000 customers conducted by Stena Recycling in Europe, 54% of consumers are placing a higher interest in extending the life of products.6

Designing for circularity is a long-term commitment to transformation. From mapping product composition and identifying material hotspots, to uncovering current bottlenecks and activating ecosystem-wide strategies, progress depends on moving from diagnostics to action. In the following sections, Deloitte explores what this looks like for the automotive industry, outlining a process that can be used by any industry to help reduce resource consumption and create value.

Global auto makers are introducing circularity infrastructure

At the global level, Renault has a series of “renew factories” across Europe, where it plans to refurbish more than 35,000 used vehicles in 2025. Its “Refactory certified” program focuses on repairing rather than replacing, using reused parts for damaged components, recycling, and incorporating energy efficiency.7 Toyota Motor Europe is launching a “Toyota Circular Factory” at its Burnaston site in the United Kingdom. The facility is designed to handle around 10,000 vehicles each year (initially), extending the use of roughly 120,000 parts and recovering key materials such as 300 tons of high-purity plastic and 8,200 tons of steel. These efforts will help to reduce future emissions associated with vehicle and sub-component manufacturing.8

Step 1. Understand the material chemistry and value chain coordination requirements of your products

The first step in the development of a circularity strategy is understanding the material composition and impact of the product portfolio. This diagnostic can help companies prioritize their efforts and align design and strategy decisions accordingly. To establish this understanding, companies should consider:

- Material composition: What materials are the components and sub-components made of?

- Significance of the impact: Which inputs account for the highest share of weight, emissions, or energy demand?

- Material chemistry complexity: Are the materials relatively simple or highly complex?

- Value chain coordination: Which materials require significant supply chain coordination either in production and design or end-of-life dismantling and reuse? Are certain inputs more vulnerable to supply chain shocks?

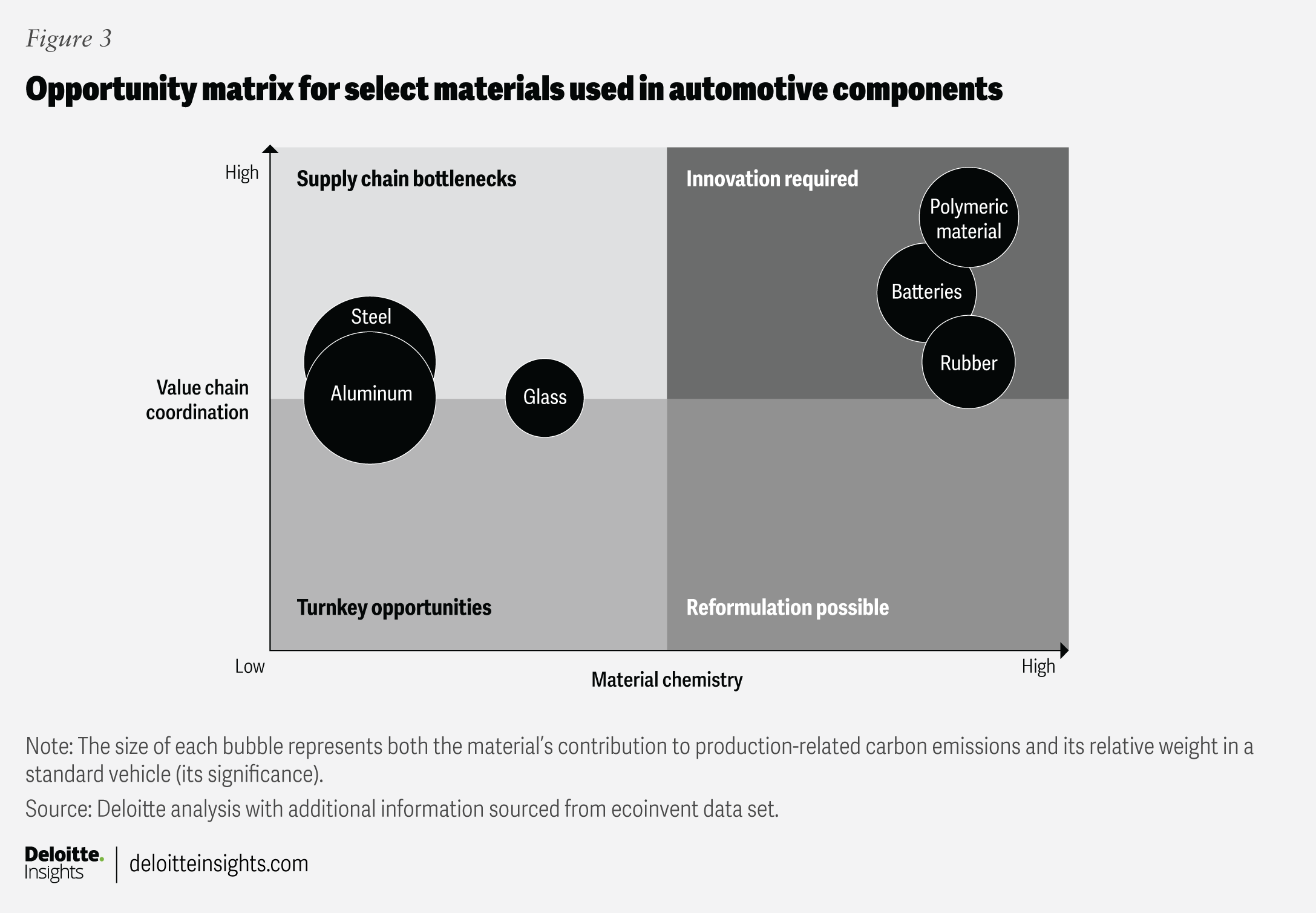

In an automobile, most components are made from nine key materials: aluminum, steel, polymeric material, battery, glass, rubber, textiles, coatings, and metals like copper. To assess the material chemistry complexity and value chain impacts of those materials, sustainability leaders can use an opportunity matrix that maps chemistry complexity against the degree of difficulty in implementing circularity (figure 3).

On the X axis, materials are evaluated based on their complexity—single element or multi-material composite—while the Y axis reflects the degree of value chain coordination and alignment needed across suppliers, customers, and recovery.

The four quadrants point to different approaches, based on where each material falls:

- Turnkey opportunities (low material chemistry difficulty, low coordination): Straightforward opportunities that can be captured quickly

- Supply chain bottlenecks (low material chemistry difficulty, high coordination): Materials that are simple in composition but require stronger supply chain alignment to unlock solutions

- Reformulation possible (high material chemistry difficulty, low coordination): Inputs that are chemically complex but can be addressed by rethinking product design or substituting materials

- Innovation required (high material chemistry difficulty, high coordination): The most challenging cases, where both technical and supply chain barriers exist, requiring long-term innovation and systemic change

Within the automotive industry, the examples of tires and engine mounts highlight how different components within the same product can face different circularity challenges.

In the opportunity matrix above, tires, predominately made of rubber, fall between the “Reformulation possible” and “Innovation required” categories, due to their material complexity challenges. That’s because tires are made from a complex blend of materials that are tightly bonded during production, creating substantial barriers to recyclability. Although these components can often be repurposed for lower value uses, such as rubber playground matting, it is difficult to use the rubber from an old tire to create a new one.

Engine mounts, which are predominately made of steel, are primarily challenged by the lack of value chain coordination both upstream and downstream. On the opportunity matrix, this places steel within the “Turnkey opportunities” and “Supply chain bottlenecks” quadrants. Steel, like aluminum, is infinitely recyclable, but realizing that potential at scale in the automotive industry depends on how the supply chain is organized.

On the upstream side, the barriers often include the cost or difficulty of integrating recycled feedstocks into established production processes, or the misalignment in incentives between suppliers and original equipment manufacturers. Design choices can further compound downstream complications. If components are produced as multi-material composites or assembled in ways that are difficult to separate, they often cannot be easily dismantled at end-of-life and repurposed into new vehicles. This leads to downcycling into lower-value applications or in some cases, disposal.

Robust measurement of the current state across material chemistry and supply chain coordination is the foundation for prioritizing effectively, aligning stakeholders, and scaling solutions.

Step 2. Analyze existing internal processes and external partnerships to identify circularity options

With an understanding of the current state and what challenges exist, it’s then possible to identify opportunities for circularity—and with them, value creation.

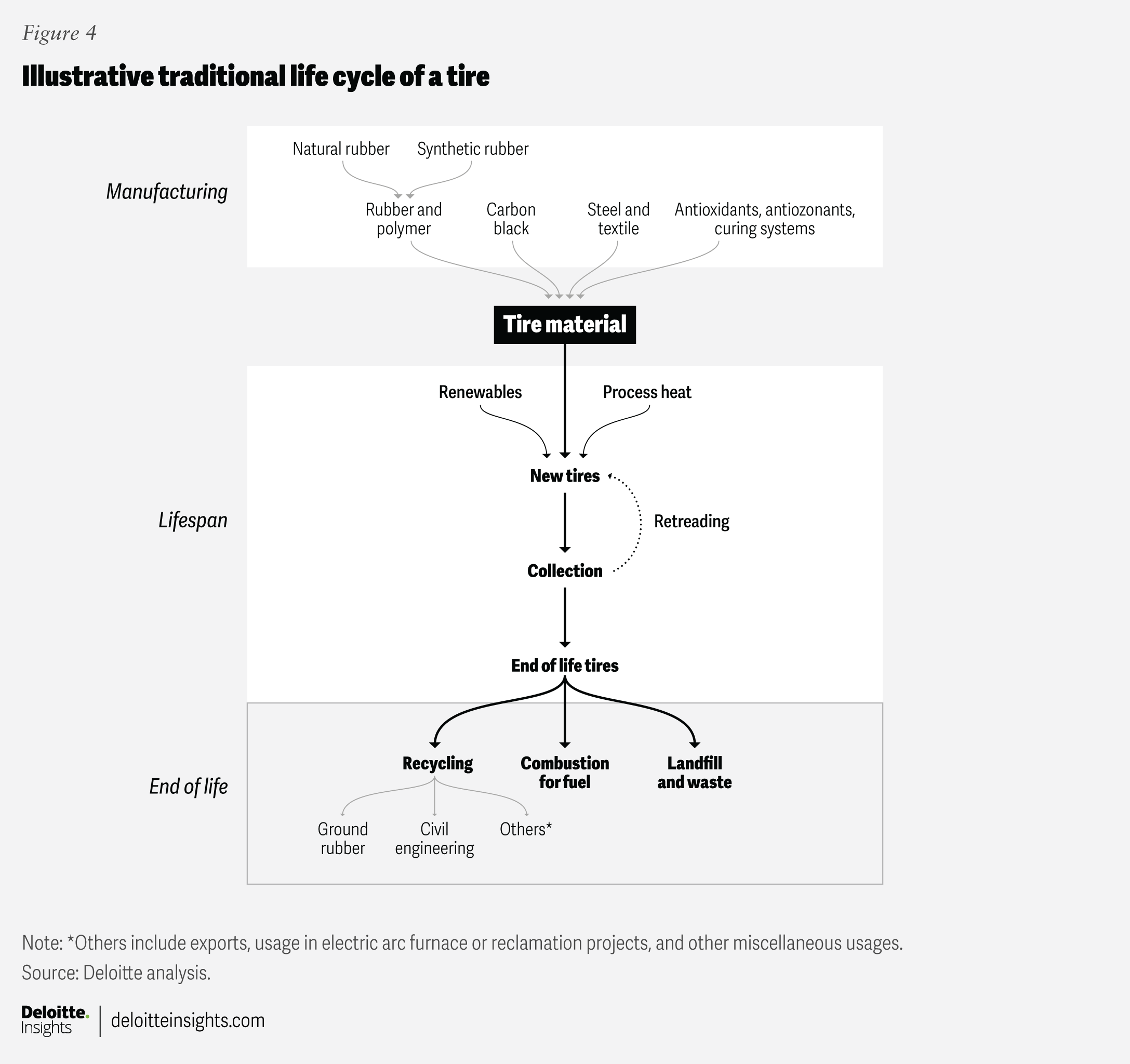

In the example of tires, there is a heavy reliance on downcycling and energy recovery, with very limited reintegration into high-value uses because the components are permanently fused into a single, inseparable structure, composed of:9

- Rubber, made from a mix of synthetic polymers and natural rubber

- Fillers such as carbon black and silica

- Steel and textiles to reinforce structure

- Antioxidants and antiozonants that help prevent the tire from breaking down, as well as curing systems (such as sulfur or zinc oxide) that are required for vulcanization

At the heart of this process is vulcanization (figure 4), in which raw rubber is heated with sulfur (and often accelerators and stabilizers) to form irreversible cross-links between individual polymer chains.

Because of these permanent fusions, the end-of-life tire recovery pathways are fragmented, with only a small share returning to high-value loops. Based on the report by US Tire Manufacturing Association, currently end-of-life tires are:10

- Processed into ground rubber for lower-value applications

- Used in civil engineering projects

- Used in fuel combustion, recovering energy but losing material value

- Sent to landfills or get disposed of as waste

- In other use cases, such as exports, used in electric arc furnace or reclamation projects, or in other miscellaneous applications

With a clearer understanding of the steps within the “take-make-waste” linear value chain for tires, we can then begin to imagine what a circular flow would look like. Several startups are innovating around tire recyclability to support a circular ecosystem.

Bolder Industries, for example, has created a carbon black alternative from end-of-life tires and rubber scrap that curbs water consumption and greenhouse gases by more than 90%, compared with traditional carbon black production.11 Similarly, Tyromer has developed a tire-derived polymer that can be reintegrated into new tires.12

In addition to exploring opportunities to use end-of-life tires into new tires, automotive companies are also looking at ways to increase the percentage of natural rubber, which is biodegradable, making it inherently more circular. With those benefits, however, come new risks, especially given that about 90% of natural rubber today comes from Southeast Asia, where increasing demand is creating deforestation concerns.13

Companies are also innovating with additional sources of natural rubber, such as dandelion plants. Dandelion roots contain natural rubber latex, are less affected by weather than the rubber tree, and have a significantly shorter growth cycle (one year compared with the rubber tree’s more than seven-year cycle).14 Innovations such as these demonstrate how rethinking the use of raw materials can introduce opportunities to overcome material chemistry complexities and allow for recycling and reuse.

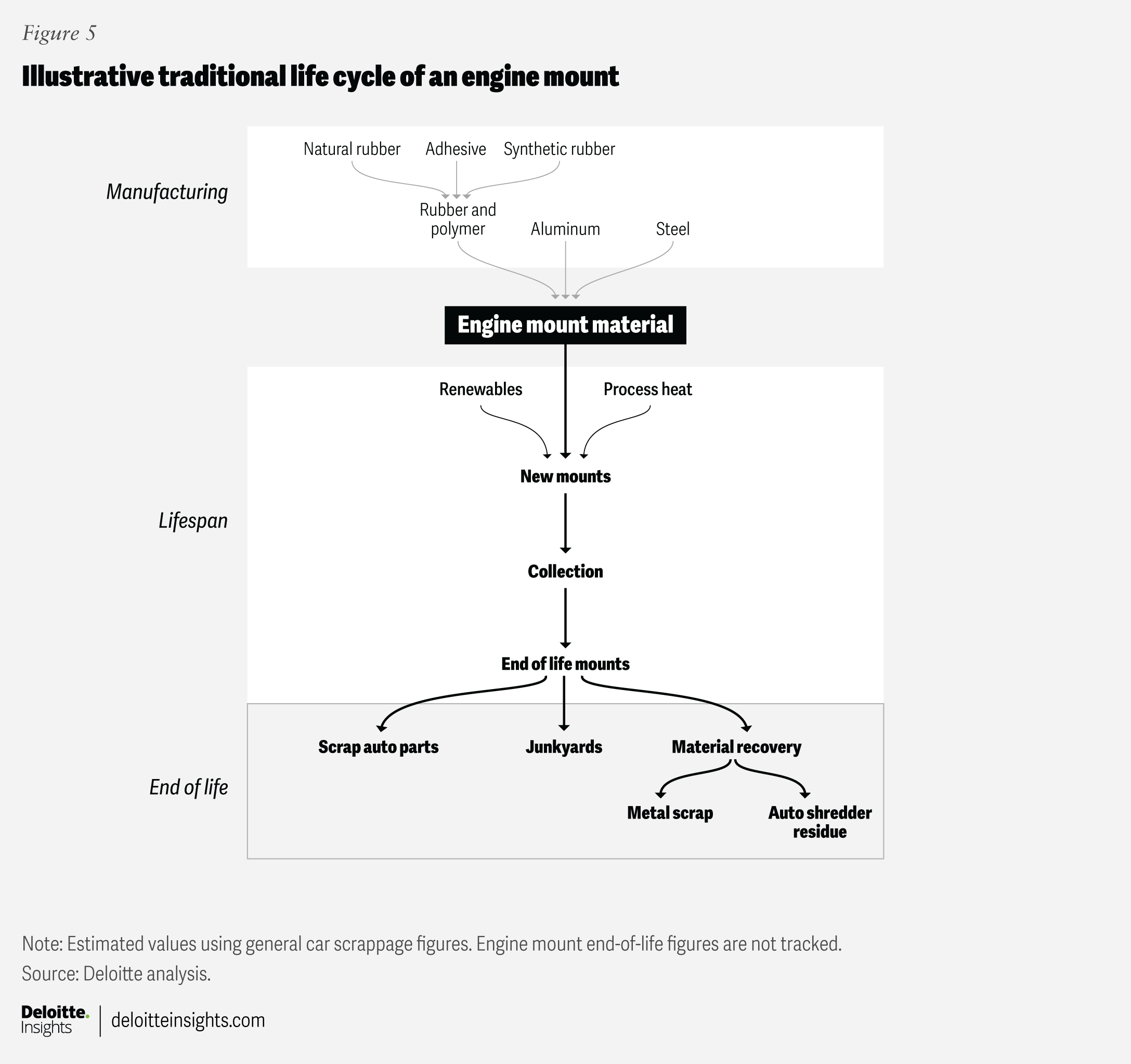

A closer look at the current state of engine mount production (figure 5) illustrates a combination of metal-forming and elastomer-processing techniques. The steel components are produced by casting or stamping, followed by precision machining to achieve the required tolerances and strength. These metal parts are then assembled with rubber or polyurethane inserts, which are molded and vulcanized directly onto the steel to create strong chemical and mechanical bonds. The resulting structure balances rigidity with flexibility, allowing the engine mount to secure the engine while absorbing vibration and shock during operation.

To advance the circularity for engine mounts, two primary coordination challenges exist. Upstream, design choices often make alloys difficult to recycle back into high-quality automotive applications. For example, aluminum alloys are sometimes fused in ways that degrade purity, preventing them from re-entering the automotive value chain at scale. Downstream, reverse logistics and treatment facilities are needed to collect and dismantle components at end-of-life.

Encouragingly, many companies across the sector are beginning to address these challenges. On the upstream side, the priority is not only developing low-carbon production methods but also designing materials and alloys with recyclability in mind. For example, Novelis has implemented scrap sorting and segregation technologies that capture high-quality aluminum from end-of-life vehicles.15 Similarly, steelmakers are piloting hydrogen-based direct reduced iron and electric arc furnaces, powered by renewable electricity. In fact, according to Deloitte’s Pathways to decarbonization series, the automotive sector represents 16% of global demand for green steel.16

Downstream solutions continue to emerge, such as LKQ Europe and SYNETIQ Ltd.’s joint venture to accelerate closed loop recovery by integrating aftermarket distribution with dismantling expertise.17 In fact, LKQ has been in the business of vehicle salvage and remanufacturing for decades: In 2024, LKQ handled 735,000 vehicles globally, selling nearly 12 million recovered parts.18 Artificial intelligence and digital traceability are also being piloted to improve classification of scrap materials, boosting automation and consistency and enabling higher recovery rates.19

Step 3. Activating a strategy for value creation

The final step is to translate these insights into a structured circularity strategy. This is the moment when diagnostics give way to action: deciding where to prioritize, what capabilities to build, and how to organize resources for delivery.

Developing a circular strategy is not only about introducing new materials or technologies. It often requires reshaping how organizations operate, with an eye toward:

- Building new technical capabilities such as embedding chemists, material scientists, or process engineers into core teams

- Creating new organizational roles focused on supplier engagement, reverse logistics, and ecosystem development

- Retraining parts of the workforce to work with advanced materials and recovery processes

Importantly, automakers—just like any company within an industry—cannot advance circularity in isolation. According to Deloitte’s 2025 C-suite Sustainability Report, 21% of surveyed companies have highlighted lack of sustainable solutions or insufficient supplies of sustainable inputs as a key barrier to advancing sustainability.20 Many solutions demand collective action across the value chain, often facilitated by partnerships, consortia, or public–private initiatives.

For automakers, the path forward involves balancing immediate opportunities with long-term investments; and scaling proven initiatives like aluminum scrap recovery today, while betting on future breakthroughs in areas such as green steel, advanced plastics recycling, and sustainable natural rubber. By formalizing these capabilities and partnerships, automakers can begin to embed circularity as a core business strategy rather than a series of pilot projects.

Preparing now for transformation tomorrow

Circularity is emerging as a critical lever for decarbonization by systematically reducing the demand for new, raw materials and keeping products in use longer. Success requires companies to introduce new capabilities, like digital traceability, and to forge partnerships across suppliers, dismantlers, recyclers, startups, and regulators.

Importantly, circularity is not just an environmental imperative but a strategic capability for resilience, cost reduction, and growth. Companies that act now can be better positioned to shape a future where products are designed for longevity, materials circulate in closed loops, and profitability and sustainability reinforce each other.

Read more

McLaren Racing and Deloitte UK developed the first F1 Constructors’ Circularity Handbook, which was commissioned by the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA), to provide teams with a step-by-step methodology to calculate their circularity journey. McLaren Racing has long been a champion of improving sustainable practices in the development and manufacture of the F1 car. Together with Deloitte UK and the FIA, it hopes the Handbook will enable all F1 teams to adopt and measure practices that minimize the environmental impact of the materials they use, while maximizing their value and reducing waste. Sharing the Circularity Handbook with all F1 constructors will allow teams and the FIA to gather data around their circularity, within the current set of racing regulations and cost cap.21

Read more here.