Trend No. 4: Talent management becomes a strategy

Enrollment management fueled the growth of higher education. Now the sector needs a “talent management strategy” to sustain itself.

College campuses are often seen as teaching and learning centers, research enterprises, and living quarters for students. But they are also workplaces. As the pandemic exhibited, running a campus is like running a city—and the Great Resignation, which has impacted every sector of the economy, has created a stark new reality for higher education leaders when it comes to talent.

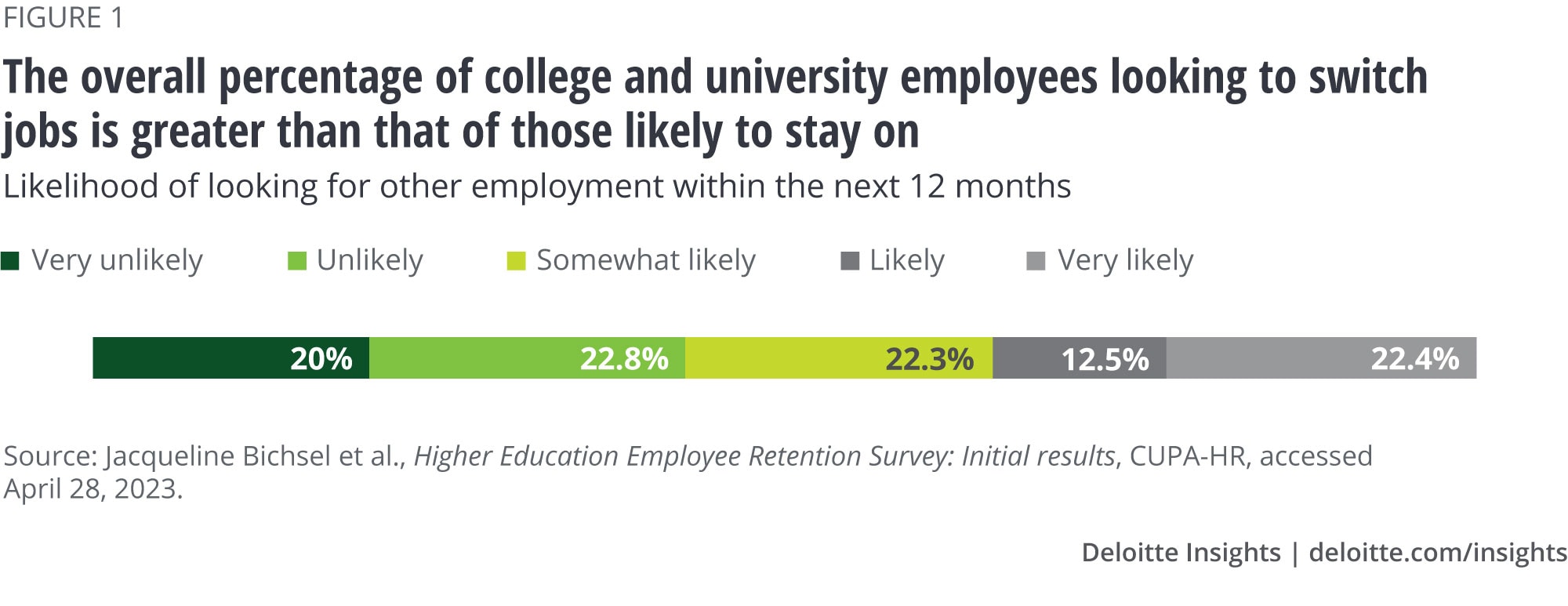

Out is the old rule book where campus employees tolerated low pay and a heavy workload in exchange for fulfilling a mission they believed in. In is a new rule book where employees want improved work/life balance, advancement opportunities, and flexible schedules with options for hybrid and remote work when it suits their needs. But the city-like aspect of college campuses hasn’t changed, leaving institutional leaders to grapple with the tension of running a vibrant, 24/7 campus community while satisfying and retaining employees. To add to their woes, majority of their workforce is considering switching jobs (figure 1).

So far, balancing both has been a struggle. Administrative offices, in particular, still feel empty, and are contributing to the perception of those from outside academia that higher education is still very much in “pandemic mode.” Indeed, faculty and staff across the sector show no signs of returning to prepandemic attitudes of where and how work can and should be performed. More than three-quarters of higher education employees think the sector is a less appealing place to work than it was a year ago.1 The College and University Professional Association for Human Resources (CUPA-HR) found that 75% of staff report increased pay as a driver for seeking new opportunities, with 42% of searches motivated by a desire for remote work arrangements.2

While colleges and universities have long had enrollment management strategies for recruiting, enrolling, and retaining students, many lack a similar “talent management strategy” that is just as critical to the institution. Even where there has been such an approach, faculty are seen as the “talent” on campuses while staff are seen as replaceable. But even faculty recruiting, retention, and engagement is suffering. Only 22% of provosts agree that their institution “very effectively” recruits and retains talented faculty. Movement away from the traditional tenure model continues, with half of institutions reporting they have replaced tenure-eligible positions with contingent faculty appointments (compared to just 17% of the sector in 2004).3

Both faculty and staff want colleges to stop making them choose between a commitment to students and their own careers and needs of their families.

Among the faculty ranks, a hierarchy of importance exists—separating senior and tenured faculty from junior faculty and adjuncts at a time when colleges and universities are emphasizing diversity, equity, and inclusion. Many faculty feel that universities have evolved in ways that have pulled them away from their core mission of working with students and conducting research to better society. They’re spending more time dealing with research compliance, managing procurements, navigating mental health challenges, and contending with outdated administrative processes and technology systems. Higher education is no longer distinctive; the private sector now provides a range of opportunities for knowledge workers seeking to make an impact in their field and within research-driven missions, all with promises of state-of-the-art labs and access to funding with fewer strings attached and less bureaucracy.

On top of all of these, the C-suite on campuses has a revolving door, and that’s particularly true of presidents where turnover continues at an unprecedented rate. While burnout from navigating the unprecedented challenges brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic is certainly driving retirements, the extreme pressures of the job are reducing the number of qualified leaders willing to step into this role. Coupled with a limited pipeline of talent due to the lack of succession planning and leadership cultivation at many higher education institutions, and the fact that over 80% of presidents historically hail from within higher education (a figure that has not changed in decades), the gaps in the top role are growing more pressing.4

Given the top position in higher education is unique—more akin to a CEO of a public company but with many of the elements of a politician—finding and preparing future leaders within the academy are vital to the long-term health of the institution and to higher education system. Until trustees dedicate time and attention to creating meaningful succession and contingency plans, the pervasive gaps in leadership will likely continue to impede an institution's ability to develop a meaningful talent strategy or make progress on the difficult path to operating model changes.

In the end, colleges and universities are knowledge organizations predicated on the idea of human development. Now they need to start designing an employee experience that matches the time, effort, and energy that they have put into the student experience. Doing so is critical not only for renewing the faculty and staff, but also for fueling the pipeline to senior leadership positions on campuses.

Call to action

Going forward, institutional search committees should consider opening the aperture of talent pool considerations and look for leaders who come from diverse backgrounds and can bring new practices to higher education, while at the same time better identify and cultivate talent from within so that new leaders are prepared to step into advanced roles. For these leaders to be embraced by campus, leaders who emerge from outside of higher education must be set up with a team to help them understand the culture and context of higher education broadly and of their institution specifically. A critical enabler of this is better training and development of boards to be partners in the success of their institutions, beginning with clearly identifying the appropriate purview of board governance, faculty governance, and management decision-making. Given the increased politicization of higher education, defining these lines, and educating boards to serve as both a partner to management in advancing the mission of the institution and as an oversite body, is necessary for success.

Beyond this, institutions must refocus on core needs (faculty, student services, research) and seek any, and all, opportunities to use technology or outsourcing to reduce work that is not core to the mission. This will require standardization and flexibility, and will allow a more narrow focus on most valuable employees in terms of learning and development, compensation, and succession planning. Now is a moment for higher education to leverage their own internal resources to train and develop staff, leaning into the degree benefits that employees are typically granted, leveraging these to build and develop their own workforce.