Global economic outlook 2026

Deloitte economists discuss the trends shaping the 2026 trajectories of over 25 countries

Foreword from Deloitte’s chief global economist

As anticipated in our last global economic outlook, elections around the world have driven notable policy changes that altered the trajectories of inflation, borrowing costs, currency values, and trade and capital flows in 2025. One significant development was that the United States raised significant barriers to trade, disrupting supply chains and creating financial market volatility. Since then, it has struck trade deals with numerous countries, reinstating some predictability in those trading relationships, albeit at higher costs. Restrictive US trade policy has also pushed other countries closer together, with numerous trade deals being inked among non-US countries.

In 2026, we expect to see the effects of these global policy shifts more clearly. Governments are adapting to a new geopolitical reality and adjusting their fiscal and structural policy plans accordingly. This will likely become more apparent in the new year. In addition, several countries are competing to remain at the frontier of technological innovation, particularly in artificial intelligence, while others are trying not to fall further behind. Significant investments to develop this innovation ecosystem are likely to continue in 2026. However, there is a risk that related spending has occurred too quickly and that a downward adjustment could be on the horizon.

In the following sections, economists from Deloitte’s firms offer their views on their respective countries’ outlooks for the coming year. We hope that readers will find these outlooks interesting, insightful, and helpful. Your feedback is most welcome, and our economists are available for more in-depth discussions on these matters.

The Americas

Argentina

– Daniel Zaga and Federico Di Yenno

Argentina will enter 2026 after two years of profound macroeconomic adjustment that reshaped its policy framework and restored a degree of stability to an economy long challenged by chronic imbalances. The program launched in December 2023 combined fiscal consolidation, the elimination of central bank monetary financing, and a managed exchange-rate regime that began with a sharp devaluation and continued with a gradual crawl to anchor expectations.

These measures, reinforced by structural reforms and deregulation, delivered Argentina’s first primary fiscal surplus in over a decade—1.8% of gross domestic product in 2024 1—and set the foundation for sustained disinflation.

Inflation, which peaked near 300% in 2024, is projected to fall to 29.4% in 2025 and 13.7% in 2026, supported by tight monetary policy and credible nominal anchors. Monthly inflation stabilized around 2% by late 2025, signaling progress toward price normalization and restoring confidence in the domestic currency.

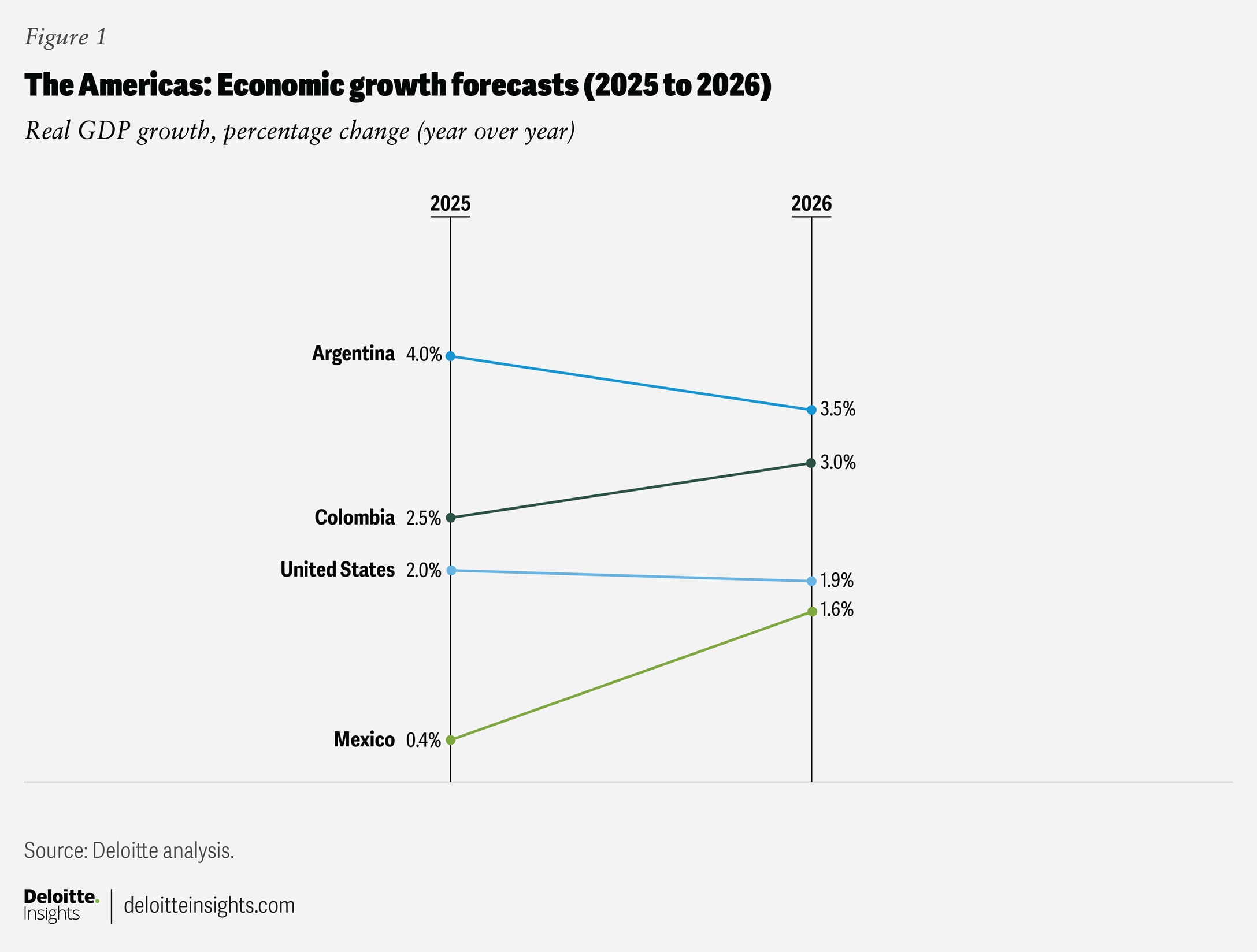

Economic prospects have improved markedly. After contractions in 2023 and 2024, GDP growth is expected to rebound by 4% in 2025 and moderate to 3.5% in 2026 as the economy transitions from stabilization to expansion. The recovery is led by consumption and construction—sectors revitalized by wage recovery and private investment—while the energy and mining sectors emerge as strategic growth drivers.

Oil and gas production is accelerating thanks to the Vaca Muerta shale, supported by new pipelines and liquefied natural gas export projects, positioning Argentina as a net energy exporter and generating an energy trade surplus after years of deficits.2 Mining, particularly lithium and copper, is also set to benefit from the Large Investment Incentive Regime (or “RIGI”), which guarantees tax and foreign exchange stability for 30 years on projects exceeding US$200 million. Announced investments already surpass US$30 billion across energy, mining, and infrastructure, signaling strong investor confidence in Argentina’s resource potential and regulatory framework. This is expected to boost investment further, as these projects advance.3

External accounts remain favorable, with a trade surplus projected at US$9 billion in 2025 and US$13 billion in 2026, despite imports recovering alongside investment-led growth.4 Net international reserves of the central bank, which stood at negative US$11 billion in late 2023, are expected to turn positive in 2026, aided by International Monetary Fund disbursements and capital inflows under the RIGI. This improvement in reserves, combined with a credible fiscal anchor, has strengthened Argentina’s external position and reduced vulnerability to external shocks.

Financial conditions have also improved significantly. Country risk ratings fell from 2,500 basis points in late 2023 to around 600 by end-2025, reflecting fiscal consolidation, structural reforms, and progress in reserve accumulation. Argentina is expected to regain market access in 2026, contingent on sustained fiscal surpluses and continued credibility of the macroeconomic framework. This normalization of financial conditions will be critical for refinancing obligations and supporting long-term investment.

Structural reforms—including tax restructuring, privatization frameworks, labor market modernization, and full capital account liberalization expected to be achieved in 2026—aim to consolidate competitiveness and attract long-term investment. These reforms, together with the RIGI, provide a stable and predictable environment for large-scale projects in energy, mining, and infrastructure, reinforcing Argentina’s potential as a regional hub for resource-based industries and renewable energy development.

The outlook for 2026 is therefore considerably more positive than in previous years. Argentina is projected to maintain fiscal discipline, deepen structural reforms, and leverage its resource endowment to secure growth while reducing inflation and restoring market confidence. The challenge ahead lies in sustaining credibility, accelerating regulatory normalization, and attracting foreign capital to consolidate the transition from stabilization to sustainable development. If these conditions are met, Argentina could enter a new phase of macroeconomic stability and investment-driven growth, reversing decades of volatility and positioning itself as a competitive player in global energy and mining markets.

Canada

– Dawn Desjardins

The Canadian economy is expected to continue to face challenges in 2026, although supportive monetary and fiscal policy will alleviate some of the stress; growth is projected to firm modestly following a subdued performance in 2025. The evolving geopolitical landscape will likely influence how Canada’s economy transitions in the year ahead. The government has introduced policy changes aimed at catalyzing business investment. Financial conditions are assumed to remain supportive, with the Bank of Canada expected to hold the policy rate steady throughout the year.

The key will be a recovery in business confidence, which dropped in 2025 amid growing concerns about Canada’s trading relationship with its largest partner, the United States. Tariff exemptions afforded by the United States–Mexico–Canada (USMCA) trade agreement are expected to remain in place in 2026, although the agreement review slated for July 2026 will likely keep businesses cautious. Consumers will feel relief from lower interest rates, although somewhat softer labor market conditions and slower immigration growth will keep spending in check.

Overall, we expect the economy to grow at a slightly slower pace than 2025’s projected 1.7%. Canada’s governments are putting on a full-court press to spur investment by reducing regulatory hurdles and boosting infrastructure spending. The federal government’s budget includes measures that will help the supply side of the economy by greenlighting large projects in the resource sector and infrastructure, boosting defense spending while supporting sectors impacted by US tariffs, and encouraging trade diversification. These measures, combined with provincial government initiatives, are expected to make a solid contribution to GDP growth in 2026 and beyond.

Labor market conditions softened in early 2025, especially in sectors most impacted by US tariffs, including steel and aluminum, lumber, and finished autos. The unemployment rate trended higher and was over 1.7 percentage points above the post-pandemic low in November 2025.5 Business outlook surveys indicated that employers aren’t looking to increase their workforce over the year ahead but, importantly, are also not looking to cut employees. Therefore, the labor market will likely remain soft; and with labor force growth reversing after strong immigration-led gains in 2023 and 2024, the unemployment rate is projected to remain around current levels.

Inflation trended higher in 2025 from the lows of mid-2024, with the headline rate in line with the Bank of Canada’s 2% target and underlying measures trading closer to the top of the 1%-to-3% target band.6 Inflation expectations, however, remain contained, and given the economy expanded below its potential pace for three successive years, price pressures are expected to remain limited. Risks of price escalation from disrupted supply chains and increased costs of Canadian imports will likely persist in 2026, although the passing down of these costs to consumers is not expected, given weak underlying demand. Against this backdrop, we expect the Bank of Canada to move to the sidelines, with the policy rate expected to remain at a slightly accommodative 2.25%.

This lower-rate environment will help ease the pressure on households renewing mortgages in 2026, many of which were taken when interest rates were at all-time lows. This will also support a recovery in the housing market after two years of weak performance.

By far, the area of the economy facing the greatest uncertainty is the export sector, where USMCA-associated carve-outs that are currently in place remain at risk. Our assumption is that the US administration will allow these exemptions to remain in place and that the review of the agreement slated for July 2026 will result in negotiations about trade irritants but will not lead to any exits from the deal.

Notably, Article 34.6 of the agreement allows any country to withdraw with six months’ notice,7 but there has been no indication that any of the parties is considering this option at the time of writing. Thus, we expect Canadian exporters to continue to benefit, and demand for Canadian goods to recover in 2026. The federal government aims to double the percentage of Canadian exports to non-US countries by spending on infrastructure to facilitate and reinforce such supply chains.

Colombia

– Daniel Zaga and Nicolás Barone

The Colombian economy is emerging from an uneven recovery, maintaining moderate growth despite persistent structural challenges and global uncertainty. After the pandemic, activity has stabilized, supported by resilient household consumption and selective sectoral dynamism. Real GDP grew 2.4% year on year8 in the second quarter of 2025, driven by entertainment, agriculture, and retail, while construction and mining continued to contract, underscoring the fragility of investment-led growth.

Domestic demand has been a key anchor for Colombia. Consumer spending grew 3%,9 reflecting household adaptability even under tight credit conditions; investment, though positive at 1.7%, remains subdued, with machinery and equipment showing robust gains while housing investment plunged over 10%,10 signaling ongoing weakness in real estate. This divergence highlights the economy’s reliance on capital goods for productivity improvements amid structural bottlenecks in construction.

Inflation remains a primary challenge. After early signs of moderation, price pressures resurfaced, pushing headline inflation to 5.1% in August,11 well above the central bank’s 3% target. Food prices have been the main driver of inflation, while core inflation eased slightly, suggesting some relief from supply-side constraints. The Banco de la República has held its policy rate at 9.25%, prioritizing price stability over growth, and is unlikely to ease before year-end.

Labor market conditions have improved gradually. Unemployment fell to 8.8%,12 and informality edged down, though regulatory changes increasing labor costs could slow formal job creation. Meanwhile, external accounts show cautious optimism: Foreign currency inflows reached US$54.1 billion,13 supported by services and tourism, while goods exports stagnated and fuel shipments declined sharply. This shift signals a slow but meaningful diversification toward agriculture and value-added sectors such as coffee and precious metals. The peso appreciated to 4,047 per US dollar, aided by lower risk premiums and investor confidence, though oil-price softness capped further gains.14

Fiscal dynamics remain a weak link. The deficit is likely to exceed 7% of GDP in 2025, prompting activation of the fiscal rule’s escape clause. A proposed tax reform seeks to raise 26.3 trillion pesos (1.5% of GDP) through higher wealth and income taxes, surcharges on financial institutions, and the elimination of fuel-related value-added tax benefits. While critical for revenue mobilization, its approval faces political hurdles and could weigh on activity via higher fuel costs.

Looking ahead, 2026 offers a cautiously optimistic outlook. Growth is projected to accelerate slightly to 2.7%, supported by stronger performance in the retail, financial, and insurance services sectors, which are expected to expand 6.7%, overtaking entertainment as the leading sector. Retail and professional services will maintain steady gains, while information and communication could see a notable rebound. Inflation is forecast to ease to 3.7%, paving the way for gradual monetary normalization and improved credit conditions. Exchange-rate stability is anticipated with the peso hovering near the 4,000 per dollar mark, while external accounts should benefit from continued momentum in services and tourism.

But risks persist. Fiscal sustainability, global commodity volatility, and external shocks remain key concerns for Colombia, although improving business confidence and sectoral diversification are creating a foundation for sustained, albeit modest, growth.

Mexico

– Daniel Zaga and Erika Peralta

The Mexican economy will most likely close 2025 with an economic growth rate of 0.4%, representing a notable decline compared with the 1.2% recorded in 2024. Factors such as tariff tensions and an uncertain business climate affected foreign direct investment (FDI), domestic consumer spending, and consequently, job creation. Likewise, the contraction in government spending and investor caution led to a 3.3% decline in industrial activity in September 2025 versus a year ago, driven by a 7.2% drop in construction and a 2.3% decline in manufacturing during the same period. In contrast, productive sectors such as agriculture, retail trade, business support, and professional, scientific, technical, health, and real estate services boosted GDP dynamism through the third quarter of the year.

Private consumer spending was also constrained by the reduction in remittance inflows, which stood at US$45.7 billion through September 2025, representing a 5.5% decrease compared with September 2024. Additionally, the lower FDI inflows discouraged job creation, particularly in the manufacturing sector.

From January to October, cumulative formal job creation reached 550,800 new positions, or 7.4% less than the amount recorded during the same period in 2024. Meanwhile, job losses in manufacturing totaled 249,000 through September of this year.

Inflation remained within Banco de México’s tolerance band of 2% to 4% between January and October. By year-end, inflation is expected to reach 3.8%, mainly driven by goods and services prices that make up core inflation. Likewise, the exchange rate is expected to close December at an average level of 18.80 pesos per dollar, which implies a 1% appreciation compared with January 2025. It is worth noting that throughout the year, the peso strengthened against the US dollar due to factors such as Mexico’s competitive interest rate, the relative stability of public debt, and the generalized weakness of the dollar.

Looking ahead to 2026, the economy is expected to see a recovery, with GDP growth reaching 1.6%, as the uncertainty generated by tariff tensions dissipates, particularly given that the USMCA’s six-year review is due to take place on July 1, 2026. In this context, investment postponed during 2025 is expected to bolster nearshoring and stimulate the manufacturing and construction sectors. Additionally, the interest rate–cutting cycle implemented by the central bank is expected to encourage investment and job creation in 2026. By December 2025, the benchmark rate is expected to close at 7%, while further cuts in 2026 could bring it to around 6.5%.

Inflation is expected to end 2026 at around 3.8%, driven by noncore inflation, which has persisted through 2025. As for the exchange rate, the dollar will likely attempt to regain strength in the first half of 2026. However, the recovery of investment—particularly through nearshoring in the medium term—along with an interest rate that remains competitive among emerging economies, would allow the exchange rate to end next year at approximately 18.70 pesos per dollar.

Mexico nevertheless faces several risks, including an increase in the fiscal deficit above 4.1% of GDP, lower remittance inflows, uncertainty regarding the performance of nearshoring, and the possibility of a profound renegotiation of the USMCA—factors that could weigh on GDP growth.

United States

– Michael Wolf

“Resilient” continues to be the best way to describe the US economy. Real GDP was 2.1% higher in the second quarter compared with a year earlier.15 Consumer spending and business investment have been the primary growth engines despite significant headwinds. We now expect real GDP to grow by a healthy 2% in 2025.

AI is likely fueling much of this growth. For example, business investment has been concentrated in information processing equipment and software. In addition, a dramatic rise in AI-related stock prices is likely bolstering consumer spending, especially for those at the higher end of the income and wealth distribution.

In 2026, we expect business investment to remain strong as companies continue to compete to be at the frontier of AI-related technological advancement. We also expect a boost to consumer spending at the start of 2026, thanks to the reopening of the federal government. Government workers who went without pay during the record 43-day shutdown have been reimbursed for their lost wages.16 Typically, this results in a boost to spending over the next couple of quarters. However, the boost in 2026 is merely making up for weaker spending during the shutdown.

Apart from the modest boost at the beginning of the year, consumer spending is expected to slow in 2026. Stock price valuations are already quite lofty,17 which will restrain gains next year. This, in turn, will likely restrain consumer spending for those at the top rungs of income distribution. At the same time, aggregate wage growth will slow further as a sharp drop in net migration holds down employment growth. In addition, businesses are increasingly passing their tariff costs on to consumers,18 which will reduce their purchasing power.

Although the Fed has cut interest rates twice this year,19 we expect additional rate cuts to occur gradually. In addition, we expect longer-term interest rates to come down even more slowly, resulting in a steepening of the yield curve. This will keep downward pressure on business investment unrelated to the AI boom. It will also restrain consumer spending on durable goods.

In our baseline scenario, real GDP growth is expected to stand at 1.9% in 2026. Much of that growth is expected to be concentrated in the first half of the year, with domestic demand slowing in the second half as delayed compensation for federal workers runs out, while AI-related consumer spending and business investment growth shift lower. However, risks are tilted to the downside, and other scenarios could easily materialize.

With so much consumer spending and business investment reliant on AI-related stock prices and anticipated returns on AI, respectively, the economy remains vulnerable to any faltering of those two drivers. Just maintaining current spending levels for consumers and businesses would create a significant drag on GDP growth. A drop in AI-related spending next year could be enough to push the economy into a recession. Other parts of the economy are more strained and will therefore not be able to make up for the loss of AI-related economic activity.

The silver lining is that the Fed still has sufficient room to cut rates and support the economy if such a scenario plays out. This is in stark contrast to the economic environment that persisted for the decade leading up to the pandemic. During those years, interest rates were already up against the zero lower bound. Today, the Fed can cut interest rates by another 375 basis points if necessary. That does not mean the process will be painless. However, it suggests that the economy could rebound relatively quickly after an adjustment period.

The Asia Pacific

Australia

– Lester Gunnion

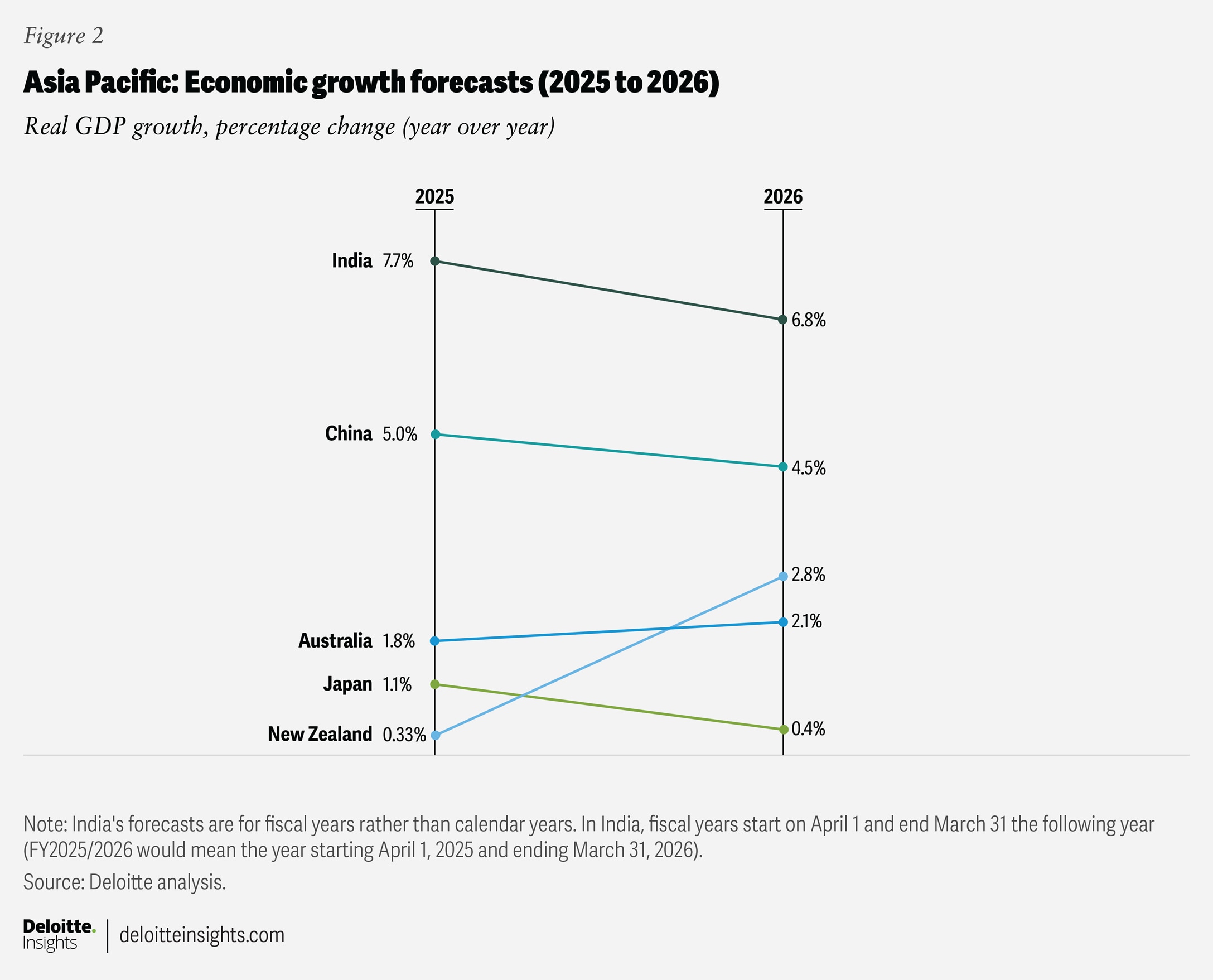

Forecasts from Deloitte’s Access Economics team suggest that Australia’s real GDP grew by about 1.8% in calendar year 2025. While this is faster than the 1% expansion in 2024, it is still far below the average annual growth rate of 2.6% in the decade before the pandemic.

Government spending has been a key driver of growth in recent years, partially counterbalancing relatively weak household spending. However, less restrictive monetary policy, a robust labor market, and real wage gains have resulted in consumer spending taking over the reins. This is likely to continue in the coming quarters. Dwelling investment, which has been subdued, is also expected to pick up pace as stronger demand supports an improvement in profitability and as supply-side reforms take effect. Meanwhile, business investment is likely to build some momentum as conditions improve over the near term and as AI investment accelerates. The public sector is expected to play a supporting role for a little longer, but overextended budgets at the state and federal levels are likely to eventually force a slowing of spending growth.

These factors point to a slightly brighter growth outlook. Deloitte expects real GDP growth to accelerate mildly to 2.1% in 2026. The forecast, however, depends on several factors, both cyclical and structural.

Just as the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) increased interest rates through 2022 and 2023 by less than other developed-economy central banks, it has also cut rates more gradually.

The RBA has been on pause after reducing the cash rate by 75 basis points in 2025. A surprise uptick in underlying inflation toward the end of the year and a historically tight labor market have pushed back expectations of a deeper and faster monetary easing cycle.

The RBA’s latest forecasts reveal that underlying inflation is not expected to return to the target range of 2% to 3% until the second half of 2026.20 If realized, there might be little room for further near-term rate cuts.

Australia’s economic growth recovery, which started in the second half of 2024, began with a higher level of capacity utilization than at the start of any other recovery phase in over four decades.21 This was mostly because the economy’s supply side has been constrained by weak productivity growth, but also partly because of the RBA’s gradual approach to policy tightening during the pandemic, which helped preserve labor market gains.

Just as in other developed economies, productivity growth has slowed in Australia over recent decades. If the trend persists over the near term, further disinflation may need to come via weaker demand growth and a loosening of the labor market.

This is not the base case: Deloitte Access Economics expects that a gentle acceleration in productivity will enable disinflation to continue over the coming quarters, albeit on a bumpy path. This could create room for further monetary easing (by about 50 basis points) through 2026.

Australia’s concerns around productivity growth extend beyond the business cycle; it is a key structural challenge, pertinent to the current global economic landscape.

Over the last few decades, robust Chinese growth helped boost Australia’s economy even as productivity growth began to falter. However, China’s growth trajectory is now slowing. Furthermore, as a small open economy, Australia is relatively more exposed to volatility in global trade. It also lacks the resources to intervene in markets at the same scale as larger economies.

If Australia is to play a more prominent role in value chains, even in areas where it possesses a comparative advantage, then it should address these challenges by unlocking gains in efficiency and reinvigorating its competitiveness on the global stage.

China

– Xu Si Tao

The current year has turned out to be a far better one for the Chinese economy than most expected. The set growth target of “around 5%” was met without relying on fiscal stimulus or monetary easing. The Xi-Trump meeting in Busan, on the sidelines of APEC Korea 2025, delivered a truce in the trade war.22 Risky assets, mainly equities, thrived; Hong Kong reclaimed its crown as the world’s top IPO market,23 while the domestic A-share market roared to a 10-year high. Even long-term interest rates ticked upward, signaling a retreat from concerns regarding the specter of prolonged stagnation and the persistence of nonperforming assets.

Yet for all its strengths, China’s economy remains unbalanced in terms of growth drivers. Domestic demand remains subdued, weighed down by a struggling property market and a soft labor market. Exports, on the other hand, have defied expectations, rising 5% to 6% in 2025 despite tariffs and export restrictions (such as the 100% import duty on Chinese electric vehicles in the United States).

Looking ahead to 2026, we expect economic growth to moderate to 4.5%. Three factors are driving this outlook. First, the property market’s downturn will continue to run its course over the next 12 months. Second, the government will press ahead with its “anti-involution” campaign, pushing nonstrategic sectors plagued by overcapacity (such as steel, cement, and solar panels) to consolidate. The central government sees a lower growth target as a necessary step to rein in these excesses. Finally, the contribution of net exports to GDP is likely to diminish.

Ultimately, China’s economic rebalancing hinges on raising the consumption-to-GDP ratio, a goal explicitly endorsed in October’s fourth plenary sessions. But what measures would be feasible to achieve this goal? Expanding trade-in programs (currently focused on small appliances) and including services like travel and hospitality can likely be done easily. Drastically cutting mortgage rates would also help, particularly if banks face rising foreclosures as property prices fall. Additional policy support for the residential property market would require reversing the current policy of curbing speculative homebuying.

A broad bailout of the residential property market seems unlikely, however, as the 15th Five-Year Plan prioritizes “moving up the value chain”—not reviving real estate as a growth engine.24 Instead, we anticipate targeted measures to strengthen the social safety net, such as subsidies for young parents and low-income households.

The external environment may also shape China’s policy implementation. Even if the US-China trade deal holds, backlash against Chinese exports could emerge on multiple fronts. The Trump administration’s renegotiation of the USMCA could extend tariffs to China’s exports to Mexico and Canada. Countries with persistent trade deficits with China—India and Turkey, for example—may impose new barriers. And even nations that heavily depend on Chinese investment, like Brazil and Thailand, could impose sector-specific tariffs—on steel, for example.

In essence, any shortfalls in external demand will likely need to be offset by stronger domestic demand, specifically through consumer spending. We forecast 4.5% GDP growth in 2026 on the premise of a more expansionary fiscal policy. We see a slightly firmer renminbi as the greenback weakens against the currencies of surplus countries, with China leading the way. A stronger Chinese currency, however, would effectively tighten monetary conditions, making a bolder fiscal stance more important.

India

– Rumki Majumdar

India entered fiscal year 2025 to 2026 with a stronger-than-expected start, as real GDP grew 8% year over year in the first half of the fiscal year, underscoring the resilience of its macroeconomic fundamentals. This was supported by strong growth in private consumption (7.5%) and gross fixed capital formation (7.6%). On the production side, gross value added grew by 8.1%, with strong growth posted by both the tertiary (9.2%) and manufacturing (9.1%) sectors.25

India’s ability to sustain such strong growth for two consecutive quarters since the beginning of the fiscal year, despite a globally uncertain economic environment, highlights the strength of the economy and the government’s relatively effective policy push (both fiscal and monetary) to boost domestic demand.

The income tax cuts announced earlier this year and the rationalized goods and services tax rates implemented during the festive season have played an important role in increasing disposable income and reducing cascading costs. Inflation, too, has continued to decline since February 2025, boosting purchasing power. Falling price pressures enabled the Reserve Bank of India to go for a 1-percentage-point rate cut in the early part of the year and another 25-basis-point rate cut in December. All these fiscal and monetary policy measures were aimed at improving credit growth and boosting household consumption.

High-frequency indicators suggest that several of the policy measures and improving price stability have led to strong economic activity. Strong growth in the fast-moving consumer goods sector (12.9%) in the second quarter of fiscal 2025 to 2026 and in two-wheeler sales (27%) in November 2025 point toward higher rural consumption. At the same time, mobility and e-way bills, as well as fuel sales, continue to signal robust economic activity this year.26

Evidently, consumer spending has remained resilient amid tariff uncertainties. There are expectations that higher consumer spending will likely boost private investments in the months ahead. Besides, easing borrowing costs and improved corporate balance sheets are expected to aid in boosting private investment in fiscal 2025 to 2026, even as global trade remains uncertain.

At the time of writing, the impact of US trade tariffs has only modestly begun to appear in India’s external balances. The current account deficit increased to 1.3% of GDP in July to September 2025, compared with 0.2% of GDP in the previous quarter. Repatriations were also higher this quarter.

We expect growth to remain consumption-led in the near term, with private investment expected to pick up as capacity utilization lingers at peak levels. Deloitte South Asia expects India to grow between 7.5% and 7.8% in fiscal year 2025 to 2026, followed by 6.6% to 6.9% in the subsequent year. This upbeat assessment hinges on the underlying structural growth drivers discussed earlier, even as trade uncertainties weigh on export prospects, especially for merchandise.

We are expecting India and the United States to sign a trade deal by the end of the year, which will help restore trade relations between the two nations. Besides, India has been proactively deepening trade relationships with diverse geographies. Recently, it signed a trade agreement with the United Kingdom and will likely conclude another with the European Union. However, risks remain, and any escalation of geopolitical tensions, energy shocks, or extreme climate events could dampen supply chains and rural incomes.

Japan

– Shiro Katsufuji

The Japanese economy has survived the economic uncertainty arising from US trade policy and domestic inflationary pressures. We expect 0.4% real GDP growth in 2026, down from the expected 1.1% in 2025. The slowdown reflects the downside impacts from US tariffs that will further materialize in 2026, and the expected backlash from the above-trend growth recorded in 2025. But the receding uncertainty around tariffs could encourage the business sector to invest and continue wage hikes, which could accelerate the pace of growth in the year after and beyond.

Notably, Japan’s economy stood at a 0.3% “excess-demand” status in the second quarter of 2025,27 almost for the first time since 2019.28 This suggests Japan will be able, after 30 years of deflation, to sustain price increases driven by aggregate demand rather than higher external costs. The labor market is generally tight, with the job openings rate at a healthy 1.2.29 The business sector is keen to increase wages to maintain necessary labor inputs and skilled talent.

As the overall inflation rate is around 3%, partially due to higher food and energy prices,30 real wage growth is still negative. But we expect real wage growth to turn positive sooner or later, once food and energy prices moderate.

Government fiscal policy is also expected to support economic growth. The new prime minister, Sanae Takaichi, is known for her “expansionary” stance on fiscal policy. She has announced the possibility of a fiscal package to help consumers, as well as a mid-term growth strategy focusing on 17 key industry areas such as AI, semiconductors, and shipbuilding.31

The Bank of Japan’s goal of “sustainable inflation accompanied by wage growth” has been achieved, and the trend will continue for the foreseeable future. We expect the central bank to continue to raise the policy rate from the current 0.5% to 1% (its neutral level) through 2026.

Japan’s economic fundamentals suggest stable domestic demand growth for the coming year. Real household consumption has shown steady growth since the second half of 2024, despite higher energy and food prices. Tourism is still booming in Japan, with foreign tourist traffic in 2025 outpacing that of 2024,32 when it exceeded the pre–COVID-19 level.

Though inflation remains a risk for mid- to lower-income households, the government continues to help consumers through fiscal measures, such as repealing the temporary additional tax on gasoline. Consumer sentiment is at a modest level mainly due to high inflation, but sentiment is likely to improve as government actions stabilize food and energy prices.

The business sentiment survey by the Bank of Japan (tankan) indicates an optimistic business sector.33 The indicator had previously shown a slight downward turn in mid-2025 when the US president announced his initial tariff plans. Now that an agreement has been reached, and with the government’s growth strategy, business sentiment should improve and remain at an optimistic level.

Exports are the key factor contributing to downside risks for the Japanese economy in 2026. The 15% US reciprocal tariff will affect Japanese exports, particularly automobiles and parts. Automakers are trying to minimize the impact by either shifting production to the United States or passing costs on to consumers. Either way, real auto exports from Japan to the United States will likely decrease. Yet a weaker yen will support exports in general.

New Zealand

– Liza Van Der Merwe, Ayden Dickins, and Elliott Lowe

New Zealand’s economy endured another difficult year in 2025. Structural matters such as productivity and uncertainty around global trading conditions continue to weigh on the country’s medium-term outlook. Although green shoots of recovery are emerging, the past 12 months have shown that optimism should be served alongside a healthy dose of caution when considering New Zealand’s near-term economic outlook.

In the year ended June 2025, New Zealand’s economic value fell 1.1%—and 2.1% in per capita terms.34 Unemployment has risen in every quarter since September 2022, reaching 5.3% in the September 2025 quarter—the highest rate since December 2016.35 Inflation remains within the central bank’s 1% to 3% target band—albeit at the upper limit of the range—with headline inflation coming in at 3% in the September 2025 quarter.36 A weak economy, paired with lower inflation, has provided the Reserve Bank with desirable conditions for reducing the official cash rate.

As lower interest rates continue to transmit through the New Zealand economy, both business investment and household consumption should begin to recover and set the economy on a path toward recovery. However, this has been delayed so far by the lag between movements in policy interest rates and their impact on household budgets (due to a strong preference for fixed-term mortgage products).

New Zealand’s net migration has declined sharply from pre-pandemic highs, driven by fewer arrivals and more departures. While migration remains positive, levels are well below the pre-COVID-19 average, reflecting a strong net outflow of younger New Zealanders to countries like Australia.37 Sustaining high-skilled migration is vital for boosting productivity, domestic demand, and long-term fiscal stability amid an aging population.

As a small open economy, trade (in both directions) is a vital part of New Zealand’s economy. New Zealand signed a free trade agreement with China back in 2008 and has steadily grown its number of similar agreements with a range of countries—including recent ones with the United Kingdom, the European Union, and the United Arab Emirates—and is in the advanced stages of negotiating one with India.

While free trade agreements are undoubtedly positive for New Zealand’s highly export-oriented economy, the current global trading environment creates a significant amount of uncertainty for New Zealand exporters. Higher tariffs globally can disrupt trade flows, depress export prices, and dampen global economic growth. Together, these factors would limit New Zealand’s ability to grow its national income through export earnings.

An opportunity amid the trade uncertainty is the potential for New Zealand to promote itself as a stable and safe nation in which to live, work, and do business—attracting foreign investment and talent. With investment expected to be diverted away from economies caught up in tariffs, New Zealand stands to benefit from additional foreign capital inflows. The question is how this can be used to fund New Zealand’s infrastructure deficit, boost productivity, and meaningfully increase the quality of life for New Zealanders.

Europe, Middle East, and Africa

Eurozone

– Pauliina Sandqvist

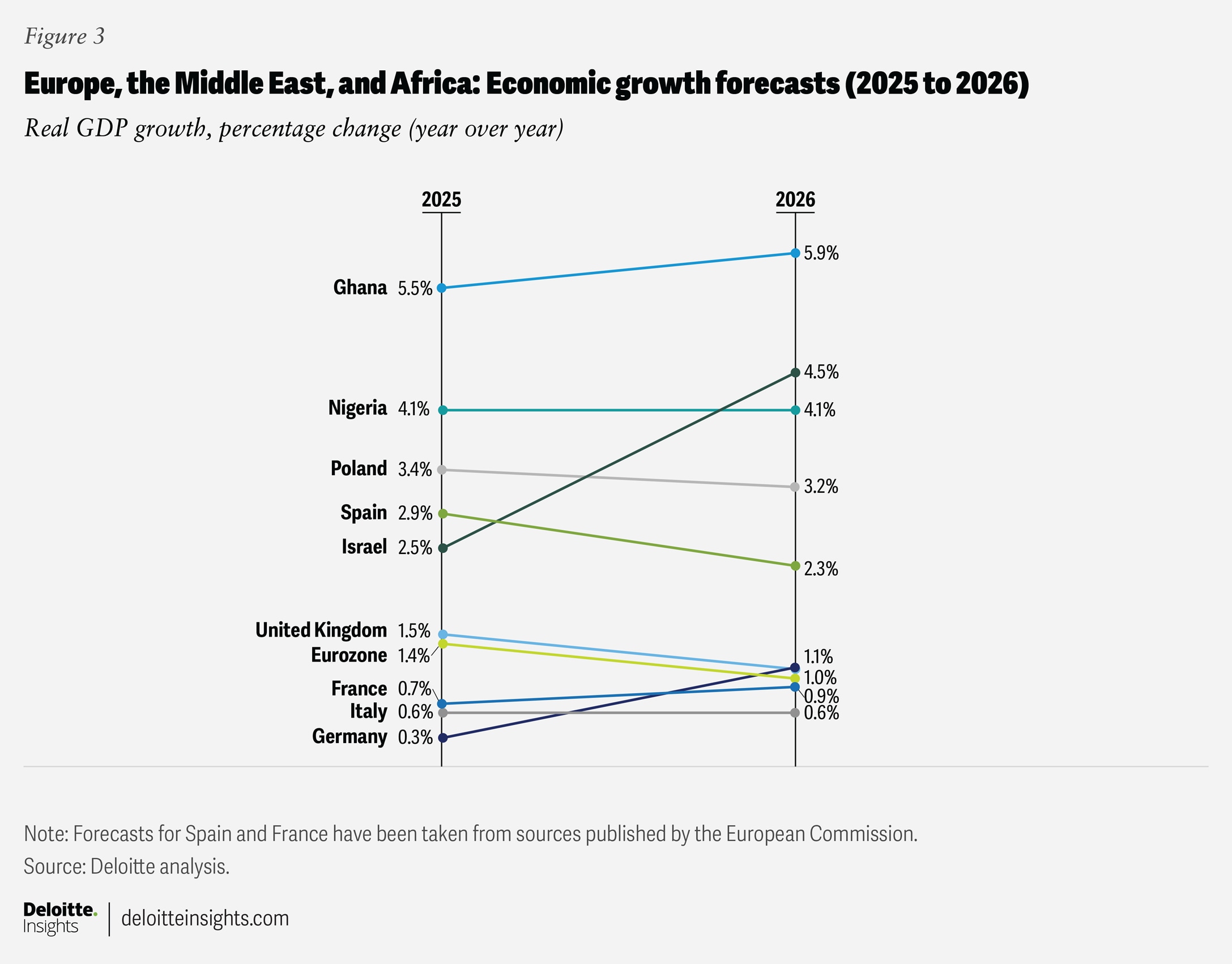

The eurozone economy has shown resilience amid a complex mix of global and domestic challenges this year. While its post-pandemic recovery was disturbed by multiple challenges, the region has avoided recession, supported by a robust labor market, easing inflation, and selective fiscal measures. In 2026, moderate growth will hinge on domestic demand and national as well as EU-level investment initiatives, but geopolitical uncertainty and trade tensions pose key risks.

Real economic growth in the eurozone is projected to reach 1.4%38 in 2025, a modest improvement over 2024 (0.8%), driven by robust private consumption and a slight rebound in investment. Private consumption benefited from labor market strength and improved purchasing power. The labor market has been a key stabilizer, with unemployment standing at 6.3%39 in September, very close to its lowest level (6.2%) in over a decade. Real incomes have recovered further as wage growth remains buoyant—even if it is softening slowly—and inflation levels have moderated.

Overall, headline inflation is likely to average 2.1%40 in 2025, with core inflation easing due to declining wage pressures and a stronger euro, which makes imports into the euro area more affordable. In line with these inflation developments, the European Central Bank announced a 25-basis-point rate cut four times this year, bringing its deposit facility rate to 2% in June. Thus, the monetary policy stance has become significantly less restrictive.

However, geopolitical and trade tensions continue to weigh on growth. The imposition of new US tariffs on European exports—particularly autos and steel—has disrupted supply chains and dampened export growth, after positive front-loading effects at the beginning of the year. Although a new US-EU trade agreement has reduced some risks, the situation remains unclear and is evolving.

Looking ahead to 2026, the eurozone economy is expected to keep expanding moderately, supported by various factors. First, sustained consumer spending growth, driven by slightly expanding purchasing power, a still-robust labor market, and a minor decline in the household savings rate, is likely to contribute positively to economic activity.

Second, fiscal stimulus related to defense and infrastructure is also expected to boost investment activity in countries like Germany. In addition to national actions, there are also multiple EU-level actions contributing to this. The “ReArm Europe/Readiness 2030” plan, introduced in March 2025, outlines a broad strategy to finance increased defense expenditures.41 The NextGen EU funds are also expected to provide a moderate boost to investment growth in 2026, particularly in southern eurozone economies.42

On the other hand, export growth is likely to be weak next year: Besides higher tariffs and a strong exchange rate, competitiveness-related challenges and strong competition from China will drag on demand for European exports. The European Union will likely try to diversify its export markets through further trade agreements. The push behind initiatives under the Competitiveness Compass, if undertaken as planned, should make Europe more economically resilient and future-proof. However, both of these actions will take time, and it is unclear how significant their positive effects will be.

Overall, the eurozone economy is projected to grow by 1.1% next year.43 Even though the annual figure is slightly lower than in 2025, underlying growth dynamics are expected to strengthen slightly.

These forecasts are surrounded by relatively high uncertainty, especially regarding US trade policy, the Russia-Ukraine war, and possible financial-market corrections driven by AI investments.

France

– Olivier Sautel and Maxime Bouter

After a modest economic rebound in 2024 (1.1%), French economic growth is expected to slow to 0.7% in 2025, according to the Banque de France, with a moderate recovery to 0.9% in 2026 and 1.1% in 2027.44 This subdued trajectory mirrors a larger global slowdown,45 as most major economies (the United States, China, Germany, and the United Kingdom) are also experiencing below-trend growth.

2025 growth levels will rely heavily on inventory rebuilding,46 particularly in the aeronautics sector, which will account for roughly two-thirds of GDP growth next year. Sustainable momentum should come from other drivers in 2026. The contribution of net exports, which was strongly positive in 2024 (1.3 points), will turn negative in 2025 (−0.8 points) and nearly plateau in 2026, due to persistent competitiveness challenges for European exporters (high energy costs, strong euro).

Household consumption should gather pace slightly (0.5 points in 2026 versus 0.4 points in 2025) but will remain constrained by a historically high savings rate (almost 19%) and weak consumer confidence amid ongoing political uncertainty. Private investment should finally pick up again, although likely only modestly (with a 0.3-point contribution to GDP), after three consecutive years of decline.

Fiscal consolidation remains at the heart of French economic policy: The public deficit is projected to reach 5.4% of GDP in 2025 (unchanged from June estimates), with further structural adjustments planned for 2026 (0.6% of GDP).47 This involves spending cuts and increases in fiscal revenues,48 limiting the scope for public sector support for growth.

On the monetary front, the ECB has lowered its key rates over the past year (from 4.5% in September 2023 to 2.15% by June 2025) but is now adopting a “wait-and-see” stance due to global uncertainties. The positive impact on investment and private demand may take time to materialize fully.

Despite economic headwinds, France’s labor market has proven resilient: Unemployment should hover around 7.5% by the end of 2025.49 However, some increase is likely due to slower job creation outside export-oriented sectors as economic activity moderates.

Inflation is expected to drop sharply to an average of 1% in 2025 (compared with 2.3% in the euro area), mainly due to lower energy prices and moderate core inflation (1.9%). With nominal wages rising faster than prices, household purchasing power will be supported in 2026.50

Political uncertainty remains a key risk: Recent events such as the dissolution of parliament and budgetary tensions have dampened both business sentiment and household confidence. While third-quarter numbers for 2025 showed an unexpected acceleration in GDP (0.5%, driven by strong industrial exports),51 this boost is cyclical rather than structural, and France’s fiscal outlook remains fragile, requiring deeper reforms.

A more robust recovery hinges on restoring collective confidence. A high household savings rate provides potential fuel for investment and consumption if uncertainty abates. However, until political stability returns and external conditions improve, the French recovery may remain hesitant.

France enters a delicate phase in which private sector confidence should replace fading public support as the primary engine of growth. While there are resources available for a rebound, namely a high savings buffer among households, their deployment depends on reduced political risk and a more favorable environment.

The fiscal adjustment necessary to reduce the public deficit below 3% of GDP will require either higher taxation or cuts in public spending. However, in an environment where private demand needs to take over from public demand, an increase in the tax burden risks weighing on household purchasing power and corporate investment capacity, thereby hindering economic recovery. The choice of path vis-à-vis fiscal consolidation will thus represent a delicate trade-off between fiscal discipline and growth.

Germany

– Alexander Börsch and Pauliina Sandqvist

After two consecutive years of contraction, Germany entered 2025 in a fragile but gradually stabilizing position. Currently, the economy is caught between cyclical tailwinds (fiscal policy) and headwinds (tariffs). At present, it seems most likely that tailwinds will outweigh headwinds, resulting in a minor recovery in 2025 and stronger growth in 2026, supported by fiscal measures.

Following GDP declines in 2023 and 2024, 2025 began surprisingly well, with modest economic activity.52 Front-loaded exports to the United States, in anticipation of tariffs, supported growth, while private consumption provided a positive impulse too. In the following quarters, economic activity slowed again, mainly due to headwinds from international trade and sluggish investment.

However, there are also some encouraging developments in 2025. One such development is the continued normalization of price pressures. Headline inflation is expected to ease to 2.2%53 in 2025 from 2.3% in 2024, improving real incomes and supporting household spending. Also, the labor market has remained robust by historical standards.

Overall, GDP is projected to grow by around 0.2%54 in 2025. The main drivers are private consumption and government spending. Nevertheless, US tariffs continue to dampen exports, limiting the scope of recovery. Even if uncertainty has partly cleared since the US-EU trade deal, it is still dragging investment levels and consumer sentiment.

Next year, economic conditions are expected to improve modestly, with fiscal policy playing a pivotal role. A moderate portion of the 500-billion-euro multiyear infrastructure package (mainly flowing into public construction investments) and substantial additional defense spending (visible in public equipment investments and government consumption) will likely boost the pace of growth.

However, implementation delays and bureaucratic hurdles mean that the full impact will only materialize gradually. Yet additional investments alone are not enough for sustainable impact; structural reforms remain necessary to strengthen Germany’s long-term competitiveness. Next to the fund, planned energy price relief (starting Jan. 1, 2026), alongside the investment booster for businesses introduced in mid-2025, will further support economic activity, especially in the industrial sector.

Private consumption should continue to contribute positively, supported by robust, albeit moderating, wage growth and a slightly improving labor market. Export activity remains subdued but should begin to recover gradually, as structural challenges in Germany’s industrial sector presumably persist, but the drag from global trade tensions eases slightly.

Altogether, the German economy is projected to grow by 1.2%55 next year. However, the pace of improvement hinges on effective policy implementation and progress in addressing long-standing challenges in bureaucratic burden, energy, and social security systems. A worsening of the geopolitical context and renewed trade policy turmoil pose further risks to this forecast. On the other hand, a peace agreement between Russia and Ukraine would likely lead to stronger growth momentum.

While the downturn appears to be over, Germany’s path to a self-sustaining and dynamic recovery will likely require political reforms and strategic investments.

Italy

– Marco Vulpiani and Claudio Rossetti

The Italian economy continued to slow down in 2025, with very moderate growth. The year was characterized by an unstable international context, due to the deterioration of diplomatic and trade tensions. Italian goods exports contracted outside the euro area, especially to the United States and for the so-called “Made in Italy” industries (such as food, leather goods and textiles, mechanical products, fashion, and jewelry, which form the basis of the Italian economy), because of the effects of higher tariffs and uncertainty over their implementation.

Moreover, a mild expansion in the construction sector contrasted with weakening activity in services and most industrial sectors. Consumption stagnated, and the propensity to save increased. Although future scenarios are subject to considerable uncertainty, stemming largely from potential new developments in trade policies and ongoing conflicts, Italian GDP is expected to grow moderately next year (0.6%), and consumer price inflation is expected to remain low (1.5%)56 and below levels expected in the euro area.

After accelerating in the first quarter of 2025, Italian GDP contracted slightly from the second quarter onward, owing to a sharp decline in exports; production growth remained lower than in the euro area. This economic volatility is mainly attributable to foreign trade. In fact, the international context remained unstable throughout 2025. The imposition of US tariffs and the appreciation of the euro against the dollar are leading to a significant loss of competitiveness for European exporters. In this context, Italian companies are facing significant export obstacles, especially affecting the northeastern regions of the country and the “Made in Italy” sectors.

Italian export volumes began to decline from the second quarter of 2025, following a sharp increase in the first three months of the year, mainly driven by sales of maritime transport equipment and a front-loading of trade before the new tariffs came into effect. Not surprisingly, goods exports contracted primarily outside the euro area, with the sharpest drop observed in exports to the United States because of the effects of higher tariffs and uncertainty over their implementation. The decline was especially marked for motor vehicles (subject to higher tariffs), food and beverages, textile and clothing products, and machinery.

On the contrary, exports of pharmaceuticals expanded in 2025, driven by the exemption of these products from tariff increases. Sentiment among Italian exporting companies57 also shows a growing perception of export barriers, rising pressure on margins, and increased operational complexity, suggesting a specific vulnerability to tariffs and geopolitical tensions outside the European Free Trade Area.

On the supply side, the cyclical weakening of GDP in 2025 is attributable both to services and to some industrial sectors, with a mild positive contribution from the construction sector due to projects under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP). In the first half of 2025, investment continued growing at a sustained pace, supported by high liquidity reserves of firms, declining interest rates, the availability of tax incentives, and the implementation of a few NRRP measures.

Household spending remained cautious throughout 2025, and real disposable income grew at slightly higher rates than consumption, translating into a strengthening of the propensity to save.58 Employment has remained broadly stable, while the participation rate has continued to rise among older workers and to decline among younger ones. Thus, households’ purchasing decisions are partly sustained by the resilience of the labor market and expectations of moderate inflation, but the propensity to save remains higher than it was before the pandemic.

Inflation was higher in 2025 than in the previous year. Deflationary pressures from the energy component were offset by increases in food prices and stronger growth in services. In 2026, consumer price inflation in Italy is expected to decline and remain below the levels expected in the euro area.59

As a final note, there is growing concern about the economic consequences of an aging population—a phenomenon particularly notable in Italy. These include risks of slower economic growth and increased pressure on public finances. Slower growth can result from a shrinking workforce, which may also lead to lower productivity, requiring actions to sustain participation and labor productivity. For example, companies are required to increase the level of digital maturity of their business processes and to explore new technological opportunities (such as AI) to support worker productivity in high–value-added activities. Another area for strong improvement is the reduction of the geographical gap in productivity.

Research from the Deloitte Observatory on Italian regions confirms that a significant gap in productivity and efficiency between the north and the south of the country remains in most sectors of the economy, linked to persistent institutional and infrastructural differences. From another perspective, a Deloitte Italy economic research study60 shows that sport and sports practice, in addition to health, social, and behavioral benefits, also play a strategic role in the country’s economic development. Sports form a beneficial factor that can help counteract the aging of the population, capable of triggering large-scale economic and social benefits, such as increased productivity and higher labor-force participation, thus contributing to GDP and employment.

Ireland

– Kate English

Ireland is a small open economy on the edge of Europe, with a population of 5.46 million.61 The country has achieved remarkable economic expansion in recent years, with the economy growing by 27% (65 billion euros) from 2019 to 2024.62 This stemmed from a robust multinational sector (tech, manufacturing, and pharmaceuticals) and steady, albeit lower, growth in the domestic economy.

Although multinationals represent only 3% of firms in Ireland, they contribute over 70% of gross value added and 27% of employment.63 Within this group, US companies play a pivotal role, accounting for nearly 32% of goods exports in 2024 64 and serving as Ireland’s largest bilateral trade partner. They have a significant fiscal impact, generating an estimated 75% of all corporation tax receipts and directly employing almost 220,000 people.65

A more fragmented trade environment or slower global economic growth, therefore, poses a significant risk to the Irish economy. However, to date, the economy has displayed resilience. The front-loading of exports by firms seeking to preempt the introduction of tariffs by the US administration has led to significant “noise” in macroeconomic data, resulting in projected GDP growth of 10.8% this year.66 A more accurate representation of domestic activity comes in the form of modified gross national income, which is still expected to increase by 3.3% this year and in 2026.67

The labor market continues to operate at record levels, although the rate of employment growth is slowing. A total of 2.8 million persons were employed as of the third quarter of 2025—a rise of just 1.1% year on year.68 This is the lowest level of growth since Q4 2012 (excluding 2020 to 2021, when the pandemic distorted the market). Employment growth is forecast to be 1.5% in 2026. The rate of youth unemployment has come into focus in recent months, standing at 12.2% as of September 2025—an increase of 1.7 percentage points year on year.

Buoyed by a strong labor market and continued moderation in inflation, consumer spending is forecast to grow by 2.9% this year. This comes as households continue to save 1 euro out of every 8 euros of disposable income.69 Indeed, households continue to accumulate record levels of savings, with deposits standing at over 168 billion euros as of September 2025 (up 6.8% year over year).70

Ireland’s strong fiscal position is eye-catching: The ratio of debt to gross national income is forecast to be just 61.7% this year, falling to 58.6% in 2026. This compares favorably with other countries such as the United Kingdom, the United States, and France, all of which have debt-to-GDP ratios surpassing 100%.

However, as this fiscal strength is heavily exposed to the multinational side of the economy, Ireland’s focus has turned to competitiveness and addressing its infrastructure constraints. Despite ranking seventh in the IMD World Competitiveness Rankings, Ireland ranks 44th for basic infrastructure.71 This gap is evident in capacity constraints across housing, water, energy, and transport. In housing, the deficit is resulting in sustained high price growth (7.4% annually in August 2025),72 decreasing affordability for many households. Just 32,990 new residential units were completed in the 12 months to the second quarter of 2025,73 compared with an estimated annual demand of 50,000 new homes each year.74 Addressing these challenges is key to sustaining growth in the future.

In the 2026 budget, the government allocated 19.1 billion euros for capital expenditure, representing 16% of total expenditure.75 This marks a significant increase compared with previous years, when capital spending as a share of government expenditure fell from a peak of 14% in 2003 to just 3.4% in 2013.

As 2026 approaches, Ireland will continue to monitor the global economic landscape while focusing on addressing domestic risks: infrastructure and housing shortages, productivity, and planning for demographic changes. As a small, open economy, Ireland’s future will likely be shaped by both external headwinds and tailwinds, making adaptability and strategic planning important.

Spain

– Ana Aguilar

Spain is expected to maintain significant economic momentum in 2026, growing at about 2.3%—1 percentage point above the eurozone average.76 Spain continues to benefit from households shifting preferences toward services. Its outlook is supported by purchasing managers’ indices anticipating ongoing expansion in the coming months. Services purchasing managers remain optimistic about 2026 (the November PMI for services stood at 55.6). The country’s manufacturing sector is also expected to continue expanding in 2026, supported by domestic demand (the November PMI for manufacturing stood at 51.5).77

In this dynamic environment, inflation will likely converge toward the ECB target of 2% but will remain slightly above eurozone levels.78

Growth in 2026 is expected to be driven by internal demand. Consumption will be the main growth driver, supported to a large degree by employment growth. The unemployment rate is expected to inch slightly below 10%, although it will remain markedly above the EU average. Wage growth will likely converge toward inflation levels (wage cost grew by 3% in the second quarter of 2025 compared with 4% in the second quarter of 2024).79

There is scope for the savings rate to fall somewhat in the stable interest rate environment, as it stood at 12.4% in the second quarter of 2025 (above its historical average of 9.6% between 1999 and 2025).80 However, households may retain a preference for saving to enable house purchasing or further debt repayment amid persistent uncertainty.

Investment is expected to maintain significant expansion in 2026 (after growing by 3.9% between the last quarter of 2024 and the third quarter of 2025), driven by moderate business indebtedness and interest rates, NextGen EU funds reaching their end date, and significant transformational challenges. Households and nonfinancial-corporation debt ratios stood at their lowest levels since the beginning of this century, and below (households) or at (nonfinancial corporations) eurozone levels.81

External demand is not expected to contribute to growth in 2026 as export expansion might be offset by import growth in a landscape characterized by barriers to trade, further euro or dollar exchange rate appreciation, and strong internal demand. The Spanish economy is less exposed to US tariffs than other European economies, as its goods exports to the United States represent about 5% of its total goods exports.82 Its exports to Europe are expected to benefit from economic recovery in the region.

Despite strong headline growth, Spain should continue to address its structural challenges, including productivity, housing, and public finances. Productivity per hour worked has grown by only 2.6% between the third quarters of 2019 and 2025, while headline GDP grew about four times faster during the same period.83

There is a severe housing shortage that will likely persist in the short term because supply has not kept pace with the growth in households, and house prices have continued to accelerate in the second quarter of 2025 (rising by 12.7% year on year, compared with 7.8% a year earlier).84

Finally, Spain’s public deficit is expected to continue on its downward trajectory (2.5% in 2025 and 2% in 2026), contributing to a mild decrease in the elevated debt-to-GDP ratio (from 100.3% in 2025 to 99.1% in 2026), according to the estimates by the Spanish Authority for Fiscal Responsibility.85

Poland

– Aleksander Łaszek and Rarał Trzeciakowski

Poland is projected to be the fastest-growing large economy within the European Union in 2025 and 2026, according to Deloitte and comparable IMF forecasts. Deloitte Poland forecasts indicate Poland will grow 3.4% and 3.2% in 2025 and 2026, respectively.

Furthermore, it is the only economy in the region whose GDP projection was revised upward and whose inflation projection was revised downward in the October IMF forecast compared with the previous April outlook. These positive outlooks extend into the mid-term horizon through 2030, sustaining a more than 35-year pattern in which annual GDP growth has been positive every year except during the pandemic.

The drivers of Poland’s economic growth are undergoing a gradual transition. In 2023 and 2024, strong domestic consumption—bolstered by significant wage increases and expansionary fiscal measures—supported growth despite sluggish performance among key trade partners, notably Germany. As external demand improves, export activity is expected to increase, accompanied by rising investment. As consumption growth moderates, GDP growth will become more balanced.

EU funds and defense spending currently serve as prominent catalysts for GDP growth, particularly in the short and medium term. However, these are not the primary contributors to Poland’s longer-term economic trajectory.

Access to the EU single market remains far more significant than financial transfers from the Union. The cyclical nature of the European Union’s multiannual fiscal framework and the upcoming conclusion of the NextGen EU initiative may lead to a concentration of spending in 2026, temporarily boosting GDP. Historical precedent shows that such surges are often followed by slowdowns. While highly visible cash flows attract attention, the impact of single market access—estimated to have increased long-term Polish GDP by at least 10%—is often overlooked.

Increased defense expenditure enhances national security, though its benefits to economic performance are less clear. In response to the escalation of the conflict in Ukraine, Poland substantially increased its defense budget. According to NATO estimates, defense spending reached 3.79% of GDP in 2024, marking the highest share within the alliance. NATO expects expenditures to increase further to almost 4.5% of GDP in 2025, and while specific plans remain unpublished, a recent Deloitte Poland (2025) report anticipated them to remain close to 4% of GDP in the coming decade. While short-term, debt-financed spending may stimulate demand and boost GDP, the literature suggests that the long-term effect of heightened military expenditure is generally negative for economic growth. Military spending should therefore be viewed as a necessary precaution rather than a driver of sustainable growth.

Economic convergence continues to underpin Poland’s development. Although discussions often focus on the role of EU funds, defense spending, or other tangible factors, the principal engine of growth remains Poland’s convergence with Western Europe. Integration into the single market and ongoing institutional alignment driven by EU membership foster capital inflows, knowledge transfer, and greater participation in global value chains. This openness enables Polish enterprises to specialize and enhance productivity—a core driver of growth over the last 35 years and one that is expected to persist as further opportunities for growth remain across various sectors.

The United Kingdom

– Debapratim De

Economic growth remains subdued in the United Kingdom. Following a strong start to the year, momentum has faltered, with output effectively flatlining over the summer and autumn months. This makes 2025 the second straight year of stop-start growth for the United Kingdom.86 It has been nearly four years since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent inflationary shock, but growth remains erratic.

A number of factors have contributed to this. The primary culprit is consumer spending, which accounts for nearly two-thirds of GDP and has barely grown since the summer of 2022.87 Inflation is now well below its peak after the Russia-Ukraine conflict, but enduring “sticker shock” and the lagged effect of earlier interest-rate rises have cast a long shadow on demand.

Consumer confidence also remains below pre-pandemic levels. Recent upside surprises in headline inflation and constant speculation over tax rises this year have fanned worries about the economy and depressed sentiment. More than two years of real wage rises have bolstered household finances, but British consumers remain cautious, saving more than the pre-pandemic norm.88

Business sentiment, as measured by the Deloitte CFO Survey, remains weak. Energy prices and supply chains may have stabilized, but cost pressures persist for corporates, now driven by higher employment and financing costs. Add to that recent geopolitical uncertainty and rising protectionism, and you have the ingredients for a squeeze on capex and hiring.

Manufacturing activity remains particularly weak. The sector seemed to have finally recovered from a prolonged post-pandemic slump last summer, but business surveys suggest it fell back into contractionary territory in autumn and has continued to shrink since. The services sector remains a bright spot, with activity expanding in all but one of the last 12 months.

Strong services output and one-off factors—such as rises in exports and housing-market activity before US tariffs and stamp duty changes took effect earlier in the year—have driven output in 2025. We expect UK economic growth to decelerate from a forecast 1.5% this year to a below-trend 1.1% in the next.

This slowdown partly reflects persistent external headwinds. With the full impact of US tariffs likely to be felt over the coming months—as US importers deplete their stockpiles and adapt their business models to the new trading environment—we expect a slight weakening in global demand.

But the key domestic driver of this deceleration is a softening labor market. With job vacancies now below pre-pandemic levels and surveys pointing to weaker private sector hiring as labor costs bite, a margin of slack is opening up in the labor market. The unemployment rate was 5% between July and September, and we expect it to rise to 5.5% by next summer. Wage growth should also edge lower and, together with rising unemployment, hold back demand and a broad-based recovery in consumer spending.

Falling inflation and monetary easing should offset this somewhat. Given cuts to energy bills, fuel duty measures, and rail fare and prescription charge freezes announced in the latest budget, we expect headline inflation to fall faster than previously forecast—to 2.5% by next spring and to approach the Bank of England’s 2% target in autumn.

This, alongside slowing wage growth and higher unemployment, should ease underlying price pressures, creating room for further interest rate cuts. We expect three 25-basis-point cuts between now and the end of next year, taking bank rate down to 3.25%—a significant reduction in borrowing costs for households and businesses.

We are forecasting sluggish growth over winter and spring, followed by a slow pickup in activity in the summer months as lower inflation and interest rates take hold, alongside a gradual recovery in global trade.

As ever, there remain sources of uncertainty. Developments in geopolitics or trade could change the course of growth. On domestic policies, the expanded fiscal headroom announced in the budget should provide greater certainty on tax policy in the face of gilt-market movements. Yet recent weeks have seen growing speculation over a potential Labor leadership contest. Were this to continue, it could introduce substantial uncertainty over the direction of future government policy, with implications for regulation, taxation, and the overall business climate.

We are forecasting a modest slowdown for the UK economy next year. If it emerges from this period with low inflation, lower interest rates, and having shaken off this stop-start pattern of growth, that would be a positive outcome.

Israel

– Roy Rosenberg

In 2025, the Israeli economy continued to be affected by the Israel-Hamas war, though the impact was more moderate compared to the previous year.

Government expenditures remain elevated, resulting in a deficit of 5%. While this figure is still high—particularly compared with real GDP growth—it is an improvement from the 6.9% deficit recorded in 2024.

Real GDP growth for 2025 is projected at 2.5%, translating to approximately 0.5% growth in per capita GDP. This represents a recovery from 2024 but remains below the average growth trajectory of 3% to 4%, primarily due to the ongoing effects of the war. Notably, in the second quarter, the economy contracted at an annual rate of 3% following a temporary shutdown of multiple sectors due to conflict with Iran.

Inflation in 2025 stood at about 3%, with roughly 0.6% attributed to a one-time effect from a 1% VAT increase at the start of the year. The shekel strengthened significantly against both the dollar and the euro, helping to restrain inflation. In the housing market, prices declined moderately but consistently for seven consecutive months—a rare and notable trend, with similar trends observed only twice in the past 15 years.

The Israeli capital market reflects positive expectations for the economy. Although rapid real GDP growth has not yet resumed, the capital market has outperformed leading global indices. For example, the Tel Aviv 35 index grew by 43% in 2025, outperforming the S&P 500 by approximately 27% (and if we factor in the increase in the exchange rate, the gap is even higher).

While none of the major rating agencies have restored Israel’s credit rating to prewar levels (or even to the levels in effect until the second-level downgrades seen in fall 2024), the country’s risk premium declined steadily throughout the year, particularly in recent months. Most of the excess risk premium generated by the geopolitical situation has been erased, with credit default swap contracts now trading below 70 basis points—almost approaching prewar levels (40 to 60 basis points) and significantly lower than the peaks in 2024 (over 140 basis points). The yield on Israeli government bonds also reflects this improvement, with the 10-year yield dropping from about 4.5% at the end of 2024 (with peak levels above 5% throughout 2024) to approximately 3.8% at the end of 2025. This decline was observed across the yield curve, indicating both expectations of a base-rate cut and a reduction in Israel’s credit risk.

The economic forecast for 2026 remains sensitive to geopolitical developments. If the ceasefire holds, Israel may experience significant recovery, which could be further enhanced if the Abraham Accords are expanded to additional countries. However, several factors may continue to restrain growth. First, the deficit rate is expected to remain high due to ongoing defense and reconstruction spending and the upcoming 2026 elections, which typically result in less fiscal restraint. Second, the election year may hinder the advancement of significant economic reforms and create uncertainty regarding future economic policy.

Conversely, several factors are expected to support economic recovery and a return to rapid growth. Declining inflation is likely to prompt a reduction in the central bank’s interest rate. Lower bond yields will enable the government to raise debt at reduced costs, improving the fiscal balance. A sustained decline in the risk premium will likely foster a favorable environment for foreign investment and further reduce government financing costs.

Assuming continued geopolitical stabilization and no major disruptions in global trade, we expect real GDP growth to reach 4.5% in 2026, inflation to stand at approximately 2%, and the deficit rate to be around 4.5%. The current debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to be 71% and to remain at a similar level through the end of 2026.

Ethiopia

– Tewodros Sisay

Ethiopia’s economy has shown remarkable resilience in recent years, but it has not been without challenges. Following strong real GDP growth of 7.3% in 2024, economic growth is projected to remain steady at approximately 7.2% in 2025.89 This moderation reflects the lingering effects of political instability in some regions, a weakening currency, and inflation, which soared to 20.8% in 2024,90 eroding household purchasing power. Yet there are signs that the tide is turning. As inflation is projected to fall to 13.2% in 2025, purchasing power should recover, setting the stage for a rebound in private consumption.91

In 2026, GDP is expected to accelerate to 7.6%. This will likely be fueled by reforms in key sectors like telecom and banking, which are attracting new investment, government spending on infrastructure and election-related activities, and the country’s strong agricultural exports.92 However, risks remain. The aftershocks of civil conflict, persistent inflation, and exchange rate volatility could still pose headwinds, and Ethiopia’s reliance on agricultural exports leaves it exposed to external shocks. Achieving the government’s ambitious medium-term growth target of over 9% will require navigating these uncertainties with care.

On the fiscal front, Ethiopia’s public-sector debt is largely owed to official multilateral creditors, who account for 82.4% (US$23.81 billion) of the total, while private creditors hold the remaining 17.6% (US$5.09 billion).93 The country is managing its debt obligations, with regular payments to the World Bank and continued support from the IMF, which disbursed US$262.3 million in July 2025 as part of a broader US$1.873 billion arrangement.94 These efforts have helped ease financial pressures and bolster investor confidence, though the benefits have yet to trickle down to Ethiopian households. Meanwhile, negotiations with private creditors are ongoing, with hopes that restructuring the US$1 billion eurobond and other debts due between 2025 and 2028 will likely provide further relief.

Monetary policy is equally dynamic. In September 2025, the National Bank of Ethiopia raised the annual credit-growth ceiling for commercial banks from 18% to 24%,95 a move designed to encourage lending and support economic activity while keeping inflation in check. The central bank has maintained its policy rate at 15%, signaling its commitment to price stability even as liquidity and exports improve. Inflation is expected to remain elevated at 13.2% for the 2025/26 fiscal year,96 driven by high food and fuel costs, currency depreciation, and increased government spending ahead of elections. Supply chain imbalances are also contributing to food inflation due to the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war and the ongoing internal conflicts in the northern region of Ethiopia.97 Over the longer term, as supply chains stabilize and economic reforms take hold, inflation is expected to moderate.