Next-gen satellite internet is transforming pricing, capacity, and regulation worldwide

Satellite connectivity sees direct-to-device growth but often faces monetization hurdles, while low Earth orbit data expansion and tech advancements help reshape deployment and resilience, and create regulation complexities

Satellite connectivity appears to be expanding faster than ever. Direct-to-device satellites are often proliferating, but struggling to monetize, while the number of low-Earth-orbit broadband constellations is growing, requiring telecom providers to address opportunities and disruptions. Alongside these developments, technological advancements are reshaping the industry, helping to enable faster deployment, greater resilience, and reduced costs. Regulatory challenges and spectrum management are also emerging as potentially pivotal factors in helping to ensure sustainable growth and integration with terrestrial networks.

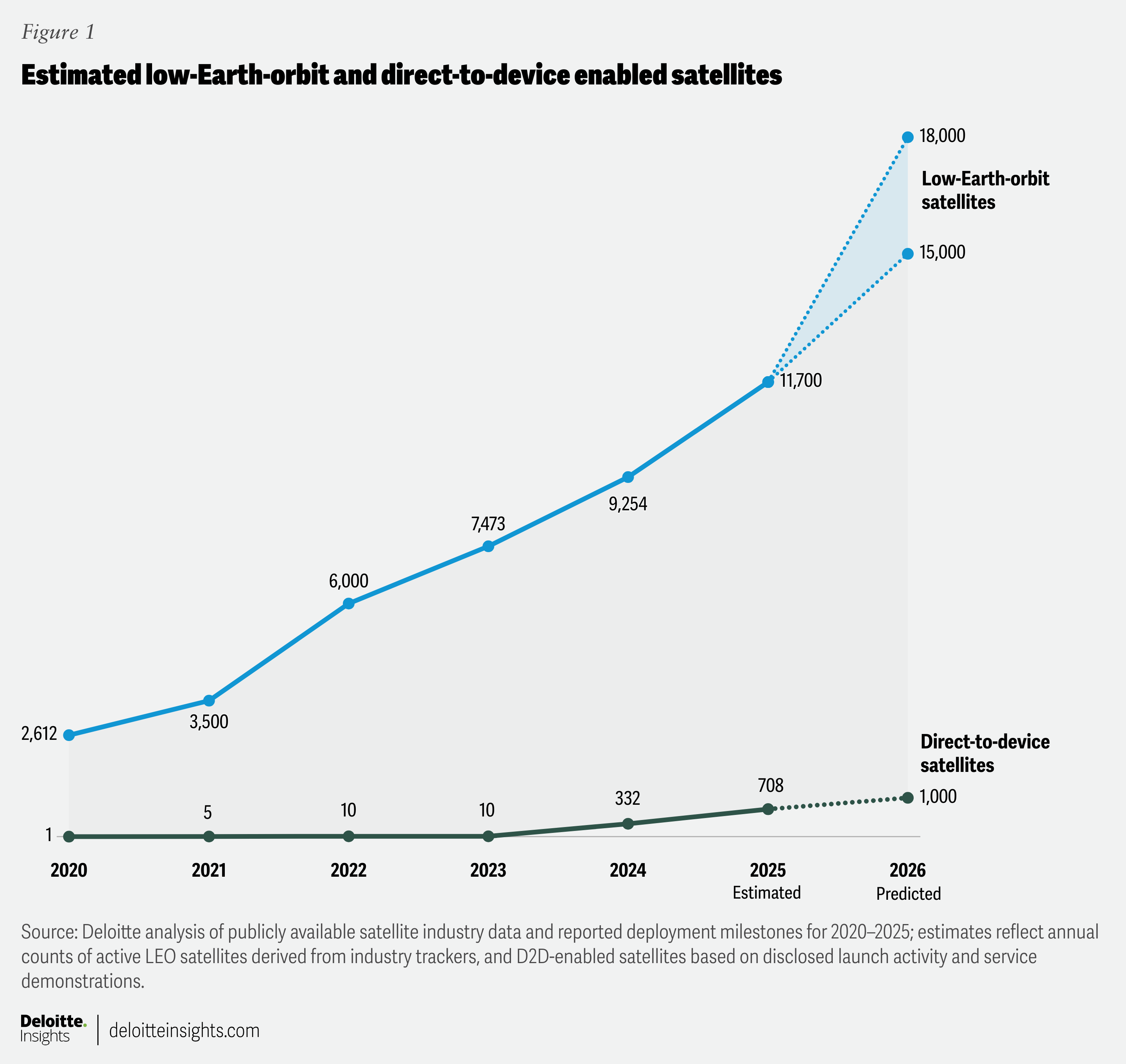

Some analysts expect low-Earth-orbit (LEO) satellite constellations to generate around US$15 billion in annual revenues in 2026,1 and Deloitte predicts that global subscribers will surpass 15 million by the year’s end.2 We further predict that the number of communications satellites in LEO will expand to five constellations3 made up of over 15,000 to 18,000 satellites by the year-end.4 We further predict that spending on direct-to-device (D2D) satellite capacity will be US$6 to US$8 billion in 2026, with over 1,000 D2D-capable satellites in orbit by the year-end; however, since monetization and business models for D2D are currently unclear, we are not forecasting D2D revenues.

D2D and LEO satellite services are deeply interconnected. At first, starting in 2019, there were multiple satellites launched into LEO, which provided data services to small satellite dishes on Earth, allowing consumers and enterprises to get low-latency broadband services in areas with little or no terrestrial coverage at a reasonable price.5 However, those signals were not accessible without pizza-sized dishes.6 In 2023, new satellites, mainly in LEO, with new equipment, new antennas, and using new regulatory permissions, were able to connect directly with devices such as smartphones. Instead of 50 Mbps or more connections over LEO with dish services, D2D in 2023 was low-bit-rate, simple messages.7 Going forward, D2D may offer higher connection speeds, but still not as fast as dish speeds.8 LEO and D2D can overlap in terms of the orbits used, and even some of the satellites used,9 but they are not identical. In September 2025, one major LEO player purchased blocks of 5G spectrum for D2D.10 It likely won’t happen in 2026: New smartphones need new chips to send and receive on that spectrum, new satellites need to be launched to use those bands, and it’s unclear what density of simultaneous users can be supported and how well the service will work indoors. But by 2028 or so, smartphone users might be able to stream video directly from space to their phones.11

D2D can connect the unconnected, but monetization remains elusive

D2D technology helps enable satellites to directly communicate with standard consumer devices like smartphones, bypassing more traditional ground-based infrastructure, offering essential, typically low-bandwidth connectivity services.12 This capability can be especially critical in remote or rural areas (including the oceans) that may lack terrestrial cellular coverage.

In 2023, Deloitte predicted the D2D satellite communication market would have approximately US$3 billion in spending on network infrastructure, mainly satellites.13 Actual spending surpassed predictions, reaching around US$4 billion in 2024.14 Current company road maps and publicly announced investment plans indicate a total capital requirement of approximately US$6 billion to US$8 billion in 2026. Of this amount, we expect around 85% to 90% to fund new satellite deployments, with the remaining 10% to 15% dedicated to replacing existing satellites.15 This rapid expansion appears to have come from multiple drivers. First, many handset makers and chip vendors have integrated satellite connectivity into smartphones: Deloitte anticipated that more than 200 million satellite-capable phones would be sold in 2024 (with nearly US$2 billion in specialty chips),16 and indeed most major smartphone manufacturers introduced flagship devices that can message via satellite.17

Second, a flurry of partnerships between mobile network operators and satellite firms helped expand D2D service availability.18 These collaborations helped enable basic connectivity (emergency SMS, low-bandwidth data) in underserved regions with no cellular coverage, tapping into a large unconnected population.

In many markets characterized by low gross domestic product per capita, rural and remote regions often remain commercially unattractive for terrestrial telecom operators. These operators typically prioritize urban centers, where higher income levels can support more substantial average revenue per user. In low-income, sparsely populated areas of some countries, revenues for terrestrial cell networks are about 10 times lower per base station while incurring two to three times higher capital and operating costs than in cities.19 Consequently, many telecom companies tend to avoid investing in infrastructure in these regions.20 At the end of 2024, an estimated 350 million people (4% of the global population) lived in largely remote areas without mobile internet networks, underscoring the D2D opportunity, although the low incomes in these areas may make many D2D or LEO data services unaffordable to consumers.21

Third, global regulators and industry standards bodies have moved quickly to help accommodate non-terrestrial networks, allocating spectrum and finalizing 5G non-terrestrial network specifications, so ordinary phones can seamlessly connect to satellites.22

LEO satellite constellations: Rapid expansion, affordable connectivity, and emerging competition

LEO has delivered high-speed, low-latency broadband through a combination of special satellites in special (low) orbits and specialized ground equipment and continues to grow: There are more satellites in LEO every week or so, more constellations of these satellites are being built, more subscribers, and more revenues.

In 2026, Amazon’s Kuiper plans to enter the market,23 potentially competing directly with terrestrial broadband providers in developing markets at lower price points than other LEO solutions. Additional LEO constellations from China’s Guowang broadband mega constellation, the Qianfan (G60/Spacesail) project,24 Canada’s Telesat Lightspeed,25 and the European IRIS² are either placing satellites in orbit in 2026 or plan to in the coming years.26 Regional initiatives are also emerging, such as the United Arab Emirates–based Orbitworks venture.27 Established operators such as Eutelsat OneWeb in Europe are upgrading their constellations to help expand capacity, improve latency, and enable direct-to-device connectivity.28

In 2022, Deloitte predicted that, by the end of 2023, more than 5,000 broadband satellites would be in LEO, providing high-speed internet to nearly a million subscribers.29 We were too conservative; by the end of 2023, there were around 7,473 active broadband-capable LEO satellites.30

LEO satellites can offer lower latency and faster connection speeds compared to traditional geostationary satellites, and some portion of the growth in LEO subscribers has come at the expense of geostationary equatorial orbit internet providers.31 LEO primarily targets users lacking traditional terrestrial connectivity options, although, so far, at prices usually higher than equivalent terrestrial broadband services.32

The distribution model for LEO satellite services is mixed, with some providers either selling directly to customers, selling through terrestrial telecom partners, or using a hybrid approach. Some may start to compete directly with terrestrial telcos in 2026 by offering more affordable subscription models, particularly in emerging markets.33

Divergent marketing strategies for providers

As the LEO broadband and D2D satellite markets evolve, Deloitte predicts two distinct distribution strategies will emerge: cooperation and competition. LEO providers frequently partner with local telcos in certain geographies, and we have seen similar partnerships in D2D in Japan, Australia, and the Philippines, for example.34

The coming competition from LEO providers

Alternatively, Deloitte predicts that certain satellite operators will pursue direct competition strategies, particularly in developing regions. These operators will offer services at substantially lower price points than terrestrial providers, aiming to capture underserved market segments through aggressive pricing and simplified service offerings. Although multiple new LEO constellations are planned or under construction, Amazon’s Kuiper is expected to be the next to start providing significant service. They are developing a monthly low-cost pricing model.35 Kuiper plans to target regions with substantial unserved or underserved populations directly, which could present a challenge to terrestrial telcos.36

That said, not all terrestrial broadband markets are equally vulnerable to disruption from space-based providers. Average broadband prices in selected developed markets range from US$33 to US$80 per month, while some developing markets have broadband prices under US$10 per month,37 suggesting that even a relatively low-cost satellite would struggle to garner significant market share in those more affordable markets. Meanwhile, other developing markets such as Brazil or South Africa, with prices in the US$21 to US$48 per month range,38 may see higher rates of take up, especially if LEO providers price at the lower end, or subsidize pricing in order to gain customers or to provide low-cost connectivity so that consumers can better utilize other services such as shopping or streaming. It should be noted that the ground station terminals needed for LEO cost US$200 to US$500 each,39 and in the developing world, this relatively high-cost consumer equipment would be unaffordable for many, even with the relatively low monthly costs (approximately US$15),40 so getting the price of the ground terminals down will also be an important factor.

Transforming satellite capacity is likely essential to unlocking next-gen connectivity

The capacity of individual satellites and the constellations they belong to can play a vital role in ensuring the effectiveness, reliability, and commercial viability of satellite-based communications, including LEO broadband services and D2D basic connectivity. The projected growth in global satellite data traffic is expected to increase 20 times by the end of 2025, presenting significant challenges in terms of satellite capacity.41 Improved satellite capacity is essential for providing wide-area coverage, supporting high-speed data transmission, and enabling connectivity in remote or underserved regions for multiple simultaneous users: Current networks are often pretty good at connecting a few dozen subscribers in the middle of nowhere, but can struggle in a moderately densely populated area. LEO needs new tech to take it to the next level.42

The availability of satellite capacity is influenced by multiple technical and regulatory factors. Technically, capacity depends on the number of satellites deployed, their individual performance capabilities, and their orbital positions.43 While theoretical models imply that LEO could support up to 10 million to 12 million satellites under ideal conditions,44 practical constraints derived from collision risks, tracking inaccuracies, and regulatory delays can limit sustainable operations to roughly 100,000 active satellites.45 Moreover, regulatory requirements, particularly related to spectrum availability in frequency bands like Ku-band and Ka-band, can limit the ability of satellite providers to expand their capacity.46 For instance, despite its global reach, Starlink has occasionally faced network congestion, leading to temporary disruptions in service availability, underscoring the importance of sufficient capacity.47 They also have needed to limit the number of subscribers in certain areas, such as southeast England.48

Many LEO companies are adopting more sophisticated technological solutions such as adaptive beamforming, dynamic spectrum sharing, inter-satellite links, and artificial intelligence-driven network optimization.49 Moreover, investments in more advanced, higher-capacity satellites, improved satellite architectures, and coordinated regulatory efforts for effective spectrum allocation will be important in balancing satellite capacity with increasing user demand and technological advancements.

LEO can be great for those who have no alternative, but it is unlikely to be a material competitor to terrestrial incumbents in most developed world markets. For example, in parts of the United Kingdom, subscriber density is already approaching its limit at approximately 0.35 customers per square km, and one analyst reports that the current Starlink network can support only around 200,000 UK homes (approximately 0.7% market share). The same report suggests that the penetration achievable with Starlink’s existing infrastructure ranges from 0.4% in Germany to 1.4% in Spain. Even with a full V2 refresh of their constellation (as opposed to the current mix of V1.5 and V2 satellites), UK penetration would increase only modestly to around 1.4% (with a stretch goal of 3% to 4%, given the full proposed 15,000 satellite constellations). While a future constellation of V3 satellites might achieve a penetration of 8% to 10%, this would likely require over a decade and substantial technical progress. There are no V3s in orbit as of August 2025.50

One other factor necessary for growing LEO and D2D overall capacity, and capacity within a given area, is ground stations, also called gateways. Ground stations are a critical part of the infrastructure, relaying data between large data centers and the satellites, managing the satellite network, and sending signals to the satellites. There are already over 100 ground stations for LEO in 2025, and a hundred more will be needed to support multiple constellations.51 Although many LEO satellites are starting to use laser communications so that satellites in orbit can communicate with other satellites in orbit (rather than having to relay everything through ground stations), this is not expected to eliminate the need for more ground stations.52 Finally, ground stations should be connected to data centers over fiber to help maximize capacity and minimize latency, which could be a revenue opportunity for terrestrial fiber providers, usually telcos.

Navigating regulatory considerations in spectrum management

As satellite communication markets grow, regulatory considerations around spectrum allocation will become increasingly important.

Deloitte predicts that LEO satellite networks offering D2D services will face significant regulatory challenges, primarily due to their need to operate within frequency bands already allocated to terrestrial cellular services. These complexities are particularly pronounced in regions such as the United States and Europe, where national and regional authorities strictly regulate cellular frequency allocations to help prevent interference and ensure equitable spectrum usage.53 In the United States, the Federal Communications Commission implemented initiatives like the “Supplemental Coverage from Space” framework, designed to integrate satellite operators with terrestrial networks, facilitating D2D connectivity.54 Additionally, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration’s policy notice for the US$42.5-billion Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment program represents a shift that expands funding opportunities for LEO satellite providers.55 The tech-neutral approach eliminates fiber preference and establishes performance-based criteria that put LEO satellites on equal competitive footing with traditional broadband technologies, potentially increasing LEO funding to US$10 billion to US$20 billion from approximately US$4 billion.56

In Europe, regulatory management is fragmented, with each national regulator overseeing spectrum allocations within frameworks established by the European Union and the European Conference of Postal and Telecommunications Administrations (CEPT).57 CEPT is actively evaluating the technical and regulatory challenges of integrating satellite services with terrestrial mobile networks.58

In Asia, similar regulatory dynamics exist but are even more complex due to diverse national policies and differing stages of infrastructure development. Countries like India, China, and Japan are actively assessing regulatory frameworks to help harmonize terrestrial and satellite frequency use, ensuring interference-free coexistence while fostering innovation and competition. India, for example, is working through the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India to outline comprehensive guidelines for effectively managing spectrum allocations.59 In China, significant regulatory reforms are being implemented to accommodate satellite communications. The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) has proactively developed policies to help streamline frequency allocations, manage spectrum interference, and encourage innovation in satellite communications. Recent initiatives by the MIIT include comprehensive frameworks aimed at facilitating the integration of satellite services with terrestrial mobile infrastructure and supporting China's strategic objective of achieving widespread digital connectivity.60 Similarly, Japan is refining its regulatory framework through the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications.61

The bottom line: Capex, regulation, and market dynamics

One implication of growth in D2D and LEO to consider concerns the capital expenditures for both space companies and terrestrial connectivity providers. Deloitte predicts that, by the end of 2026, the cumulative investment in D2D satellites and in LEO broadband constellations will reach approximately US$10 billion62—and some of those constellations will have D2D capability on some of their satellites. That US$10 billion has been spread over multiple years since 2019, but even if all of it had been spent in a single year, it’s startlingly small compared to annual global telco capex, which is about US$300 billion per year, as of 2025.63

One reason D2D and LEO partnerships matter for many terrestrial telcos is that they are “capex-lite” ways of meeting the ongoing pressure to connect 100% of populations, no matter how remote or rural. Serving those populations with wired or wireless technologies would cost orders of magnitude more than partnering with space-based solution providers (which have no capex requirement) or even investing in them directly. AST SpaceMobile has raised money from global players such as Vodafone, AT&T, and Verizon, for example, and the total amount raised is a tiny fraction of those companies’ annual capex.64

As constellations age, and with the average LEO satellites having a four- to five-year life expectancy, that capex will likely stay high over time, with 20% to 25% of the constellation needing to be replaced annually.65

Satellite-based broadband is emerging as a strong alternative to certain traditional terrestrial services, especially in developing regions. For instance, in Nigeria, a LEO satellite provider is now the second-largest internet service provider just two years after entering the market.66 It seems possible that a single LEO provider, or more likely LEO providers as a group, could become the largest provider in many emerging markets with current low levels of terrestrial broadband connectivity.

Regulatory landscapes will likely evolve significantly, with governments balancing innovation and market competition against national security and sovereignty concerns. New international regulations and standards for spectrum allocation, orbital debris management, and cybersecurity will likely emerge to help address the complex challenges arising from the rapidly expanding LEO environment. Public Emergency Communications System and Emergency Services and Public Safety Requirements exist and vary from country to country. The device makers will have to follow various emergency communications and public safety regulatory frameworks in different countries.

LEO operators will need to navigate complex agreements with terrestrial mobile network operators, employing strategies such as spectrum-sharing or leasing arrangements under conditions designed to prevent interference. Critical regulatory concerns include sophisticated interference management strategies like dynamic spectrum allocation and geographic beam shaping.67 Balancing terrestrial operator rights with satellite-enabled connectivity enhancements will likely require extensive regulatory oversight and robust collaborative models between satellite operators and terrestrial providers.

Although we focus on the consumer LEO broadband market, a large and robust enterprise market is likely to emerge over the next few years, with the number of enterprise subscribers growing nearly tenfold by 2030 to 3.4 million.68 While that is a smaller number of subscribers than the consumer market today, enterprise customers are likely to have much higher monthly revenues and lower churn than consumers.