Delivering on equity with mobility technologies

How transportation agencies can promote equitable innovation

Anant Dinamani

Kelley Schneider

Patrick Zubin

Justin Porter

Introduction

Without warning, The COVID-19 pandemic altered how our communities work, move, and connect. Three years later, some of these changes—such as the white-collar shift to remote work—have proven durable.1 Patterns of shopping, employment, and leisure continue to evolve, reflecting changing public preferences and anxieties.2

The transportation industry, responsible for keeping people and goods moving, has been on the frontlines of COVID disruptions and the emergence of new travel patterns. The pandemic’s impact, however, has been distributed unevenly across different demographics, sectors, and modes. Inequalities embedded in our transportation system have become clear to many observers, as has the important stabilizing role played by public transportation agencies.3

Throughout the worst surges and business closures, these agencies provided critical access to mobility for millions of “essential workers,” often low-income and minority travelers, who continued to travel to medical facilities, grocery stores, warehouses, and other critical sites daily. Inequities in where people worked and how they travelled highlighted new opportunities for transit and mobility agencies to address broader societal challenges, and as the pandemic progressed many agencies renewed their focus on their core ridership in service of broader equity and development goals.4 This focus now has become a societal imperative, particularly in view of the looming impacts of climate change on vulnerable populations and society at large.

To achieve a sustainable post-COVID recovery while meeting equity goals, transportation agencies should consider making a strategic commitment to real change. New technologies, service plans, and infrastructure projects can advance these objectives—and should be accompanied by meaningful performance metrics to measure success and guarantee accountability.

To limit the impact of future crises, this commitment will require adaptability. Developments in technology, performance measurement, and agency resources have produced a new array of tools and best practices that transportation agencies can use to make strategic decisions more quickly and accurately than ever before. But leaders must ensure that community needs remain at the center of planning.

Transportation agencies need a renewed framework to assess and measure these projects without diverting focus or resources from their core operations. This paper offers such a framework, incorporating cross-industry insights to provide leading practices for technology deployments that can enhance mobility and equity for all travelers.

Delivering on the “equity” pillars

Technology can be a key enabler to delivering on the principles. However, technological solutions rarely make broad access an initial priority. From Tesla to Uber, most recent mobility innovations began by targeting higher-income customers and only later moved to mass-market offerings.22 But government agencies have different stakeholders and different incentives. They are beholden to elected officials and ultimately the public at large, and as such must make sure that new technologies are accessible from inception. Reversing the normal, market-driven order of operations requires a different approach.

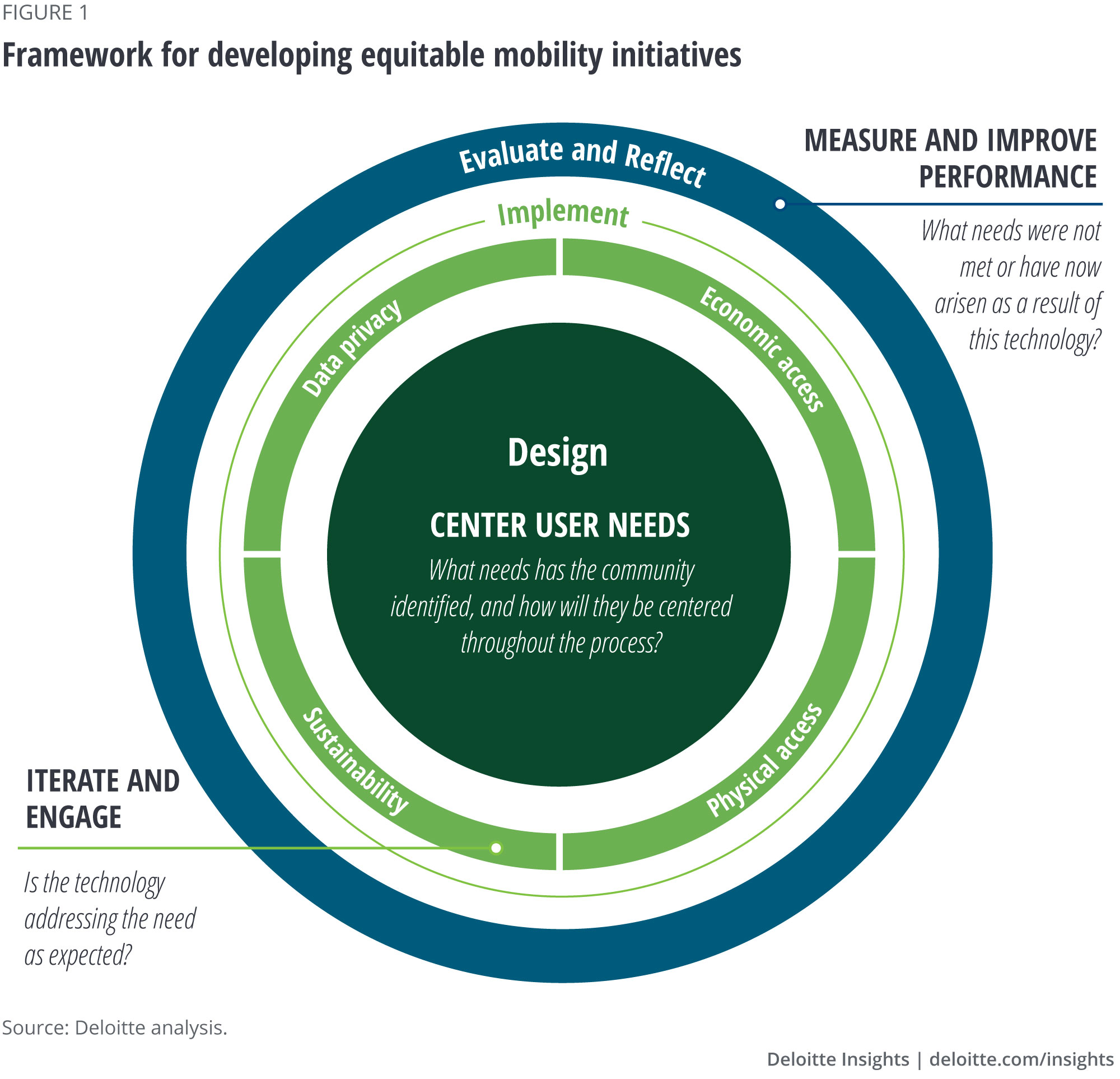

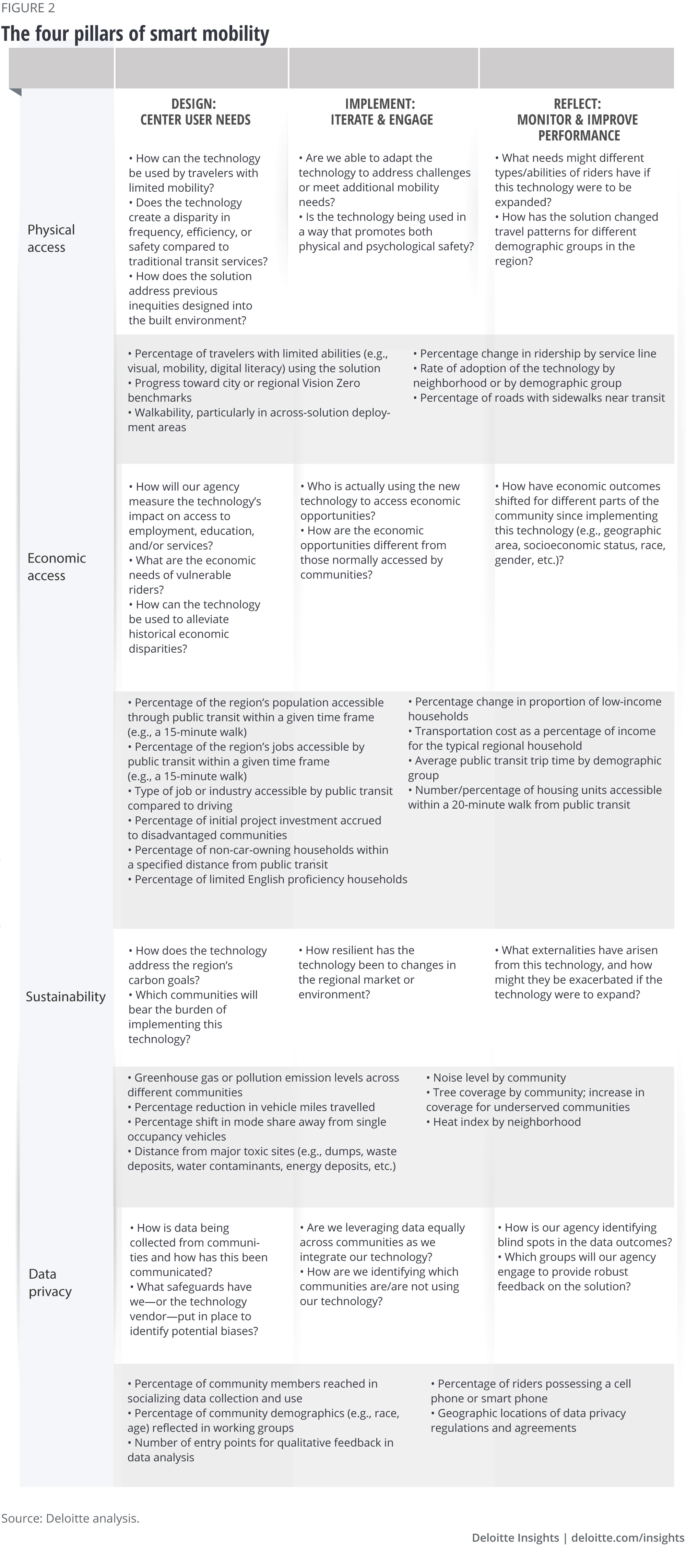

To adapt to smart mobility, transportation agencies must assemble an increasingly diverse set of ecosystem players to serve their constituents’ shifting needs, working to grow ridership as they modernize their systems. And they need to do it in a fiscally constrained environment that may see fluctuations in ridership while maintaining safe and reliable operations.23 It’s a daunting task, but one that can benefit from structure. Agile methodologies can help to evolve how transportation agencies plan for and execute technology-centric programs. Using the four pillars of equitable smart mobility outlined above, together with insights from industry leaders and experts, we developed a framework to help transportation agencies continuously plan and execute customer-facing technology projects in an agile fashion with community engagement throughout the process (see sidebar, “A human-centered approach to identifying, developing, and integrating innovative mobility solutions”). This framework provides a set of leading practices for agencies to consider throughout the lifecycle of a mobility technology project.

A human-centered approach to identifying, developing, and integrating innovative mobility solutions

Promoting equity across all four pillars is essential at every phase of a project, but agencies should take particular care to address capabilities specific to each pillar within each phase of a project.

Mobility innovations

Transportation agencies across the United States have used a range of strategies to balance equity and innovation, keeping mobility ecosystems functioning and accessible while encouraging modernization. Successful efforts can be models for government leaders aiming to effectively put principles into practice. While the following examples represent only a small sample of mobility innovations in the marketplace, they offer useful lessons about adopting mobility technologies. As always, agencies should examine potential negative effects as well as best practices when integrating a new mobility solution.

Integrated payments: WMATA

The Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA, or Metro) rolled out mobile payments using mobile phone “wallets,” allowing riders to pay for transit service simply by tapping their phones at gates, fareboxes, and Metro parking lots. Riders also can add to their mobile wallets without having to make a trip to a kiosk or retail location to purchase a card or add value.29 Importantly, WMATA’s mobile “SmarTrip,” like the plastic version before it, continues to be accepted for payment by all transit operators in the Washington D.C. metropolitan region, enabling seamless regional travel.

WMATA concurrently released its SmarTrip app, which provides an interface for card account management as well as transportation providers, including a view into card information, benefits, and passes. To ensure that riders without access to a smartphone or cashless payment method can continue to ride, WMATA offers SmarTrip cash payments through its ticket vending machines and at select retail locations.

WMATA continues to advance partnerships for both trip information and payments. Matt Hardison, senior vice president of Planning and Business Transformation at WMATA, notes that the agency worked with ride-hailing companies to support integration of Metro services as a travel option in their apps and is working with its regional shared bike service on programs to advance shared bike use through Metro—eventually integrating with SmarTrip as well. “Our goal as an agency is to make sure people have the best transportation options possible to meet their needs,” Hardison says, “all the while improving our customer service and the value of our services.”30

Mobility data equity: Caltrans

To help California better allocate project funding while combating climate change and “supporting public health, safety, and equity goals,” Caltrans’ Climate Action Plan for Transportation Infrastructure outlines a number of strategies, action steps, and frameworks. For example, Caltrans is developing a transportation equity index to identify equity-based priority populations and plans to establish related metrics to evaluate transportation impacts. Currently, “there is no widely used transportation-based index to identify equity-based priority populations, nor a method to evaluate or prioritize transit agency project proposals,” says Amar Cid, manager of Caltrans’ Race & Equity Program.

Caltrans is seeking community and stakeholder input on the environmental, accessibility, and socioeconomic indicators it will use to evaluate transportation projects. This process will allow stakeholders to share data and evaluate projects from a health and equity perspective by layering together and weighting indicators from disparate sources. The tool includes indicators such as nonwhite and/or Hispanic population percentage, diesel particulates, traffic fatalities and serious injuries, so that Caltrans can prioritize projects with the most significant social equity benefits. To ensure the tool’s success—and break down silos to develop and prioritize regional approaches with positive social equity outcomes—Caltrans encourages local transit agencies to join forces and use the index. Cid notes that this collaboration can help “break down silos and develop regional approaches to mobility.” 31

Mobility-as-a-service: DART

Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART), serving a sprawling 700 square miles, faces different challenges than agency counterparts in denser regions, as it must address the needs of constituents in comparatively remote areas while serving a total population expanding faster than its transit infrastructure. DART looked to private transportation companies to fill the gap. In 2018, it launched a pilot first mile/last mile (FM/LM) partnership with Uber to explore ways to increase system access, ridership, and efficiency. The agency has since integrated the program as a booking option in its GoPass app, allowing DART to normalize fare methods—for instance, making riders eligible for reduced Uber fares due to their presence in a designated on-demand FM/LM service area.

However, app-based services can exclude riders lacking ready access to smartphones, credit cards, or banking abilities, not to mention those who are simply uncomfortable with new technologies. DART therefore needed to find a way to work with private partners to integrate new mobility technologies in a way that would provide FM/LM service to all potential customers. The agency now allows riders to book rides by phone and use multiple payment options, such as loading cash payments into the GoPass Mobile App through retail partners. According to DART’s chief innovation officer, Greg Elsborg, “We’re working to make sure cash-paying customers continue to have the same ease of experience as riders with digital payment methods, and we’re exploring additional opportunities such as upgrading our ticket vending machines to accept cash as well as cards to add digital account balances to our GoPass Tap Cards and Mobile App.”32

Transportation planning equity assessment: Broward MPO

In 2018, the Broward Metropolitan Planning Organization (Broward MPO) in Florida started developing a process to evaluate its plans more consistently and comprehensively against Title VI and other federal and state nondiscrimination policies. The goals of this assessment included greater consistency and efficiency in Broward’s planning process, as well as more meaningful community outcomes and the proactive identification of potentially adverse impacts. “We wanted to assess equity at all levels of the project lifecycle,” says Peter Gies, the agency’s systems planning manager. “We knew that looking at equity through just one lens doesn’t give the full picture.”

To perform the evaluation, Broward first analyzed demographic data to identify areas with a higher proportion of protected populations as part of a broader environmental justice process. This process was complemented by community engagement, including with Broward MPO’s Citizens Advisory Committee, which provided local feedback and due diligence on quantitative findings. The assessment mapped specific “equity areas” in the region, as defined by a composite equity score that can be used to accommodate planning efforts across a variety of regional agencies. The tool is designed to be iterative so that even as it serves as a model for other regions, it can remain flexible to community input and feedback.

A regional approach to equitable innovation

As travel patterns continue to evolve, transportation agencies should reevaluate their assumptions about planning, delivering, and maintaining services, including how to expand the mobility choices available to their customers. As other analysts have noted, obstacles to this goal are regional in nature, underpinned by governance and institutional constraints.33 To reach consensus on scalable solutions in the long term, transportation agencies need to develop solutions and policies across an integrated web of transportation partners. To take the first step toward building this network, transportation agencies should focus on iterative near-term collaboration at the regional level, powered by local connections. Local agencies that engage directly with customers and communities can build support for transportation initiatives, while regional agencies can tie together local outcomes to serve broader goals including equity and sustainability. The private sector is a key player in mobility innovation, and disruptions have previously served to highlight challenges in public transportation’s ability to quickly adapt to market movements.

Where should public transportation leaders begin with convening the mobility players needed to address equity, climate, community, and public health concerns? First, they must align their vision and goals for their regions and cultivate support for them. It’s important to include leaders whose organizations engage directly with constituents, to understand the mobility needs and challenges communities face. Next, leaders should evaluate the roles and space between transportation agencies in the region, identifying which are best positioned to develop and deliver innovative mobility solutions tied to their distinct roles, whether it’s front-end mobile apps or back-office billing platforms. These steps should be supported by an equitable, smart mobility framework and an iterative, human-centered design process that allows communities to cocreate alongside agencies toward a shared future vision.

Ultimately, “smart mobility” alone cannot solve the transportation challenges communities face; the future of mobility will require a transformation of government processes and a renewed approach to regional transportation planning and management. An equitable mobility ecosystem requires support from regional and local agencies, private partners, and the public if agencies are to transform the way our communities move and connect.