Organizing to drive change

How to establish a well-organized office for data-driven success

Crises, from pandemics to hurricanes, have a way of underlining the importance of the chief data officer by laying bare gaps in an organization’s data readiness and infrastructure. For example, need data on which homes in an area have flood insurance? That may only be possible with access to data that is clean, complete, and properly integrated. The high-quality data needed for crisis management and resolution requires that a CDO’s operation be equipped properly and advocate for data interoperability, modernization, and usability.

The office of the CDO (OCDO) was once intended to improve data availability, quality, and compliance. Now, organizations are beginning to recognize the value of their data, and OCDOs are being called upon to transform essential business processes and drive enterprise strategies that align data and AI with business priorities and value.

Not having a well-organized OCDO exposes organizations to operational inefficiencies, regulatory penalties, security threats, and lost opportunities. On the contrary, a well-organized OCDO can empower CDOs to transform data into a strategic asset, drive innovation, ensure compliance, reduce operating costs and waste, and create a data-driven culture—ultimately delivering measurable business value.

Here, we explore the various OCDO service levels, reporting relationships, and operating models that can help agencies optimize data operations and achieve their strategic objectives.

Understanding CDO operating model service levels

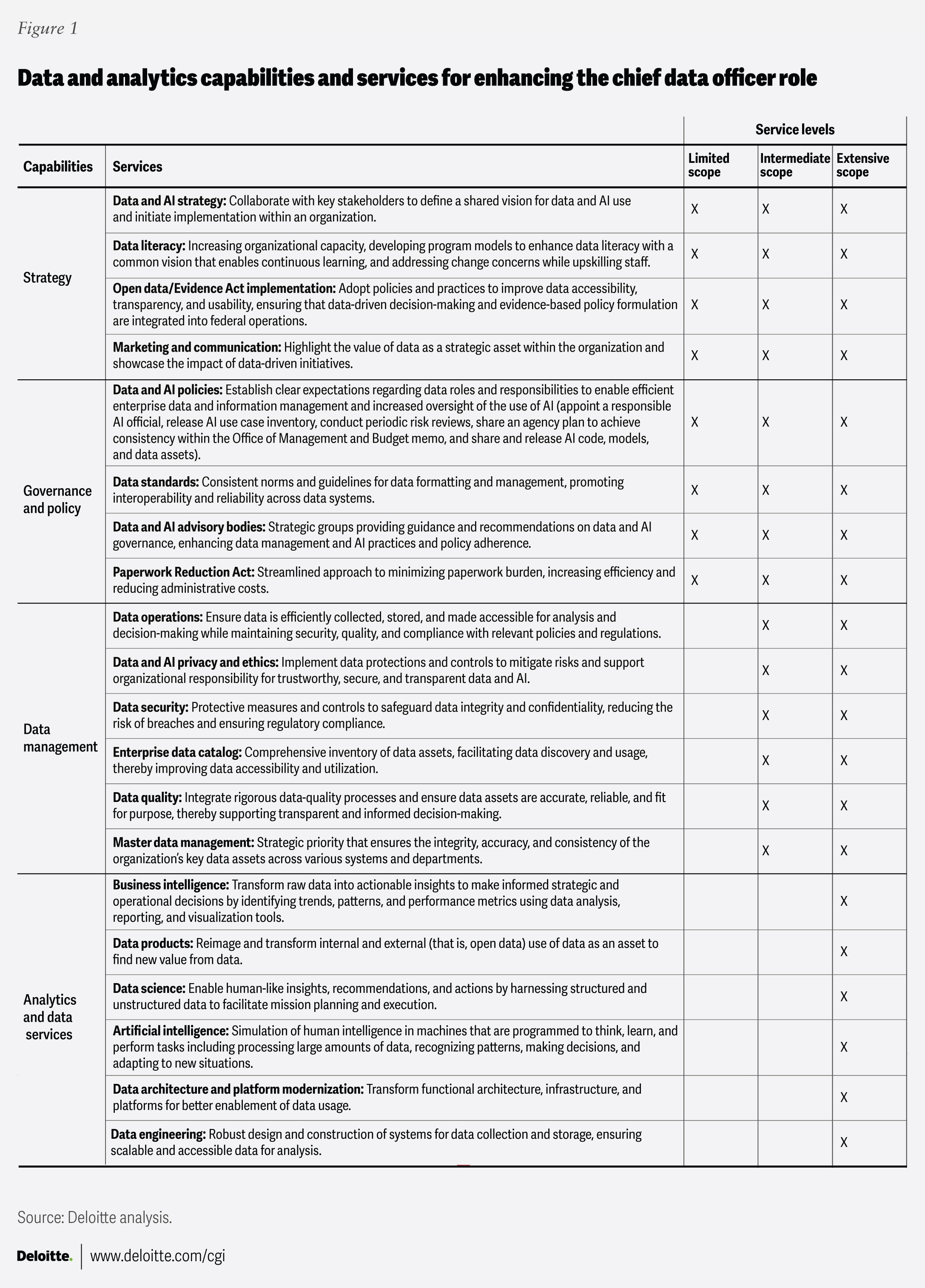

Understanding each CDO operating model service level—limited scope, intermediate scope, and extensive scope—is equally important to align the chief data officer’s role with an organization’s strategic goals and operational needs (figure 1).

The limited scope service level focuses on foundational elements such as strategy development, governance, and policy to ensure that data initiatives are aligned with organizational goals and regulatory requirements. This scope is ideal for organizations needing strong data policies without extensive implementation support.

The intermediate scope service level builds on the foundational capabilities established by the limited scope service level by incorporating more advanced data management practices, balancing consistency and control with the flexibility needed for effective planning and implementation.

The extensive scope service level encompasses all previous capabilities while emphasizing the strategic, cross-functional management of data and analytics, driving innovation and competitive advantage, and incorporating advanced analytics and AI capabilities.

Together, these service levels provide a structured framework for organizations as they mature and evolve in their data modernization journey.

Many organizations evolve across operating models and service levels over time as their maturity, funding, and capabilities change. Understanding this evolution helps integrate the CDO role more effectively into broader organizational strategy.

Reporting models for a CDO office

The reporting structures for CDOs have similarly evolved as the role has grown. Initially, many CDO positions were created to comply with legislative requirements, such as the Foundations of Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018, which mandated the establishment of CDO roles in various federal agencies.1 As these roles demonstrated their value in providing high-quality data to support new technologies such as artificial intelligence and machine learning, the perception of CDOs shifted from being primarily compliance-focused to being integral to operational and decision-making processes.

Where the CDO role falls within the organizational hierarchy can significantly impact their visibility, authority, and influence.

CDO reporting to the agency head: When the CDO reports directly to the government agency department head or CEO, several strategic advantages emerge. This structure is used to align data-driven decision-making with the agency’s overarching goals and priorities. By having the CDO report to the CEO, the agency can foster a culture in which data is integral to policy formulation, operational efficiency, and service delivery. Furthermore, reporting directly to the department head or a similar executive gives the CDO greater authority and influence to drive effective data strategies and minimizes conflicts that may arise when peers or priorities compete for resources.

CDO reporting to the chief information officer: The relationship in which a CDO reports directly to the CIO offers some advantages; however, according to the 2024 CDO survey, this reporting structure remains challenging.2 One potential positive is that a CIO could provide technical funding and resources to execute the data mission that may not be otherwise available to a CDO competing with the CIO for resources. However, a CDO reporting to the CIO is still limited in organizational power due to constrained personnel resources and funding constraints. Additionally, according to the 2024 Federal CDO Council survey, the CDO role was more limited in influence when reporting to the CIO or chief technology officer, as this was the only reporting relationship in which CDOs were classified as GS-15s, rather than members of the senior executive service.3 This means the junior-ranked CDO is inhibited in truly driving strategic change.

CDO reporting to other executives: This reporting relationship elevates the CDO role to a peer level with chief information security officers and CTOs, providing greater emphasis on—and access to—executive focus on data activities. This gives the CDO equal footing in strategic discussions alongside other senior executives, fostering a more balanced approach to resource allocation and decision-making. That said, there are some disadvantages as well. For example, yet another layer of complexity and potential resource constraints can arise if a CDO reports to a CISO or CTO. A CDO may be limited to the CISO’s budget, which is already a small portion of the CIO’s budget. If a CDO reports to a CTO, there is a high probability that the CDO’s resourcing needs will take a back seat to the CTO’s, whose primary focus is research and development and innovation.

Choosing the right operating model for the right organization

So, you know the scope of your services and who you report to. Now, what is the right operating model for you?

The right operating model will help CDOs achieve the organization’s vision and data strategy. This strategy can set out the goals the CDO is trying to achieve and the service offerings that are important to achieve them. Simultaneously, the governance structure can determine how the CDO’s success is measured and what resources are available to deliver those service offerings.

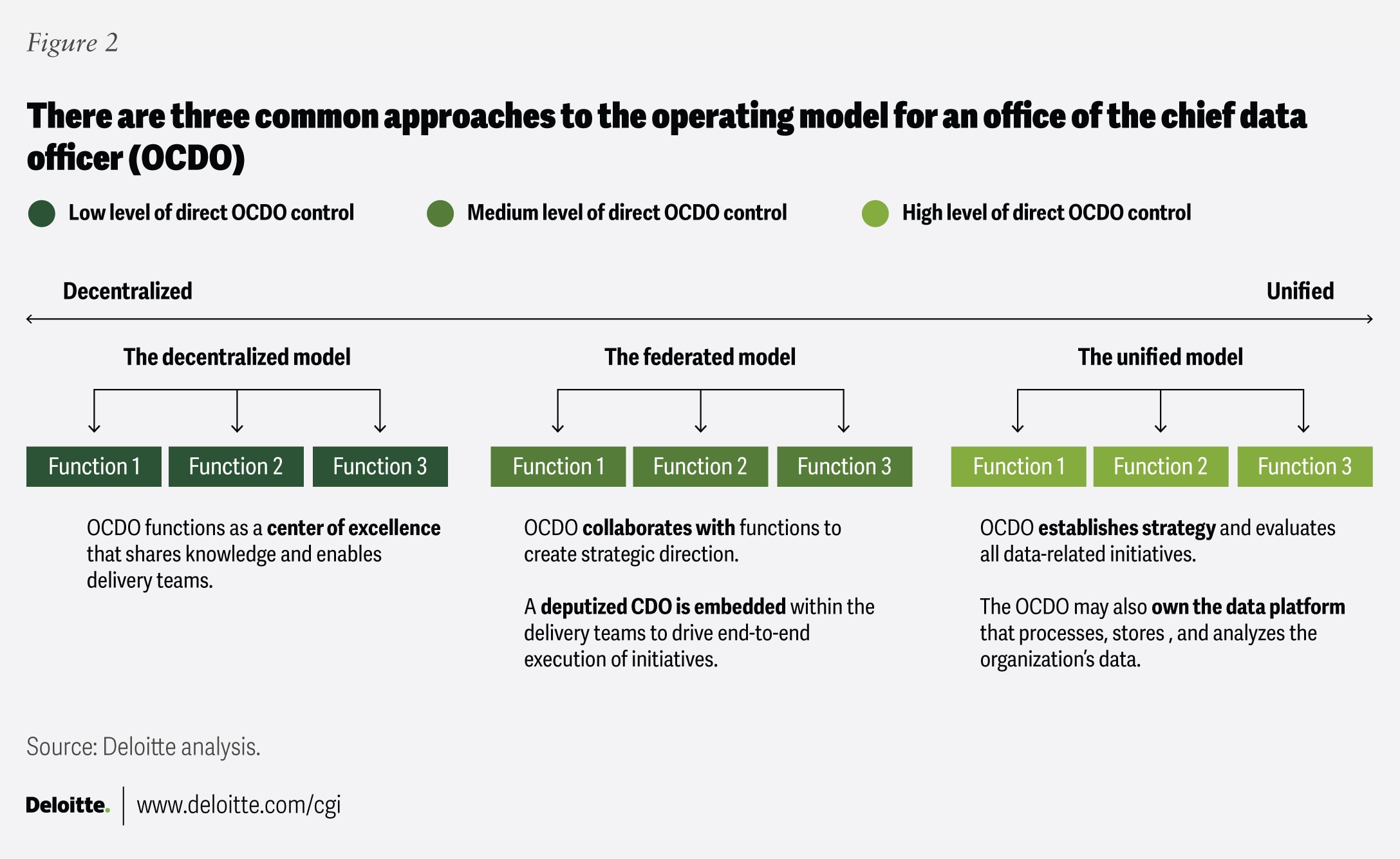

At a high level, three common CDO operating models are typically found across organizations: decentralized, centralized, and hybrid.

Decentralized model

In a decentralized model, the CDO functions as a center of excellence, serving as the data policy leader for an organization. Most data management roles, such as stewardship, metadata management, data quality, and data security, reside within business units. The primary role of the CDO is to share knowledge and enable delivery teams across functions. This model emphasizes training and data literacy governance, aligning closely with the original intent to emphasize talent development and local enablement.

For many organizations, establishing data centers of excellence can help the training and data literacy efforts of the decentralized model. For example, the Internal Revenue Service established the Office of Research, Applied Analytics, and Statistics (RAAS)4 and the state of North Carolina created the Government Data Analytics Center to serve as data centers of excellence.5 By grouping most analytical talent within a center of excellence, CDOs can increase efficiency while potentially creating a better work environment for data workers.

Centralized model

The centralized model concentrates the responsibilities of data governance, management, and analytics within a central CDO office. The CDO establishes strategy and evaluates all data-related initiatives. The CDO may also own the data platforms that process, store, and analyze the organization’s data, enabling centralized oversight and implementation in alignment with the unified model’s goal of end-to-end governance.

The Department of War’s Advana is an example of a data platform in government. Advana provides users with quick, easy access to common business data, decision-support analytics, and data tools that may otherwise exist in different locations and require extensive time to discover.6

Establishing a formal, centralized data management office can be challenging and often requires substantial investment to build the necessary infrastructure. This investment may be justified, particularly if the organization aims to maximize the value of its data while remaining compliant and maintaining adequate privacy, sensitivity, and security controls.

Hybrid model

A hybrid model is considered the most balanced among the three models. In this model, the CDO collaborates with business functions to create a strategic direction. The OCDO maintains a medium level of control, and a deputized CDO is embedded within delivery teams to drive the end-to-end execution of initiatives. The CDO establishes policy, data standards, and other data-centric tasks to ensure that decisions are aligned with the organization’s data strategy. However, execution is carried out independently by business units.

This approach is often used by government CDOs and is especially practiced by large, highly federated agencies such as the Department of War (DoW), the Department of the Treasury, and the Department of Homeland Security. For example, the DoW has not only a central CDO but also CDOs for each military force and service.

Where the decentralized model exercises data governance via training, the hybrid model exercises data governance via proxy. Because an agency’s central CDO cannot be everywhere, this model balances the control of centralized governance with the agility required by business units, empowering efficient, agencywide data management.

Getting started

While the operating model structure depends on the specific organization in which the CDO works, there are a few common steps to consider.

- Continually check alignment with strategy. As we have said in other articles in this series, a data strategy can be a great way to kick-start change within an organization, but it should not be a one-and-done exercise. The operational structure chosen to execute that strategy should be assessed continuously to ensure it supports both the data strategy and organizational goals.

- Define governance and metrics. The role and reach of CDOs can change dramatically depending on who they report to. After selecting an operating structure, CDOs should clearly define reporting relationships and how success will be measured, tailored to the model adopted.

- Foster peer-to-peer relationships. A CDO’s ability to communicate the value of data and analytics to other executives is critical to gaining their support for key data initiatives.

- Identify new areas for improvement. As CDOs are increasingly seen by organizations as a source of both operational and mission value, they should look for new opportunities to improve performance and impact. This approach can help build trust with other executives and better position the CDO to play an even bigger role in future transformation initiatives.

- Invest in communications. Finally, while CDO work may center on data, it requires coordination between offices and people. As Caryl Bryzmialkiewicz, an early government CDO and the first for the Health and Human Services Office of the Inspector General, puts it, “The ability to motivate and to pull people together depends on good communication skills and a bit of marketing.”7

CDOs are succeeding in government. Not only are their roles required, but they are increasingly seen as a source of operational value. If CDOs take the time up front to think about the right operational structure, they can deliver value to the public both now and in the future.