From data assets to data apps

CDOs can drive the change from data assets to data apps to help organizations realize the significant benefits of data

Matt Gracie

Mark Urbanczyk

Mark White

Prabhu Kapaleeswaran

Chief data officers (CDOs) have found multiple ways to use data—to more efficiently direct resources to those in need, to personalize services using artificial intelligence (AI), and to reduce operational costs through data-driven optimization.

But while data is a key element in the aforementioned transformations, how organizations think about data can be a challenge to realizing even more benefits. Traditional views of data as an asset that should be carefully guarded can hinder data-sharing, thereby acting as a challenge to greater efficiency or more personalized services. Data-related products such as apps have, today, demonstrated how they can help unlock the value of data for the public.1 Such data products bring together many different sources of data and decode it for the users in a way that can answer their business question.2 Think of a data product as the routing feature in your maps app: It can combine many different train and bus timetables in a way that helps you know how to get from point A to B fastest, not just see a set of raw timetables. A data app will often build from data products, layering in cognitive automation to help users understand the business rules that may be hidden in the data. If the routing information in your mapping app is a data product, then you can think of predicting travel times—using AI to understand the hidden patterns in historical traffic patterns, then applying those patterns to travel times in a clean user interface—as a good example of a data app.

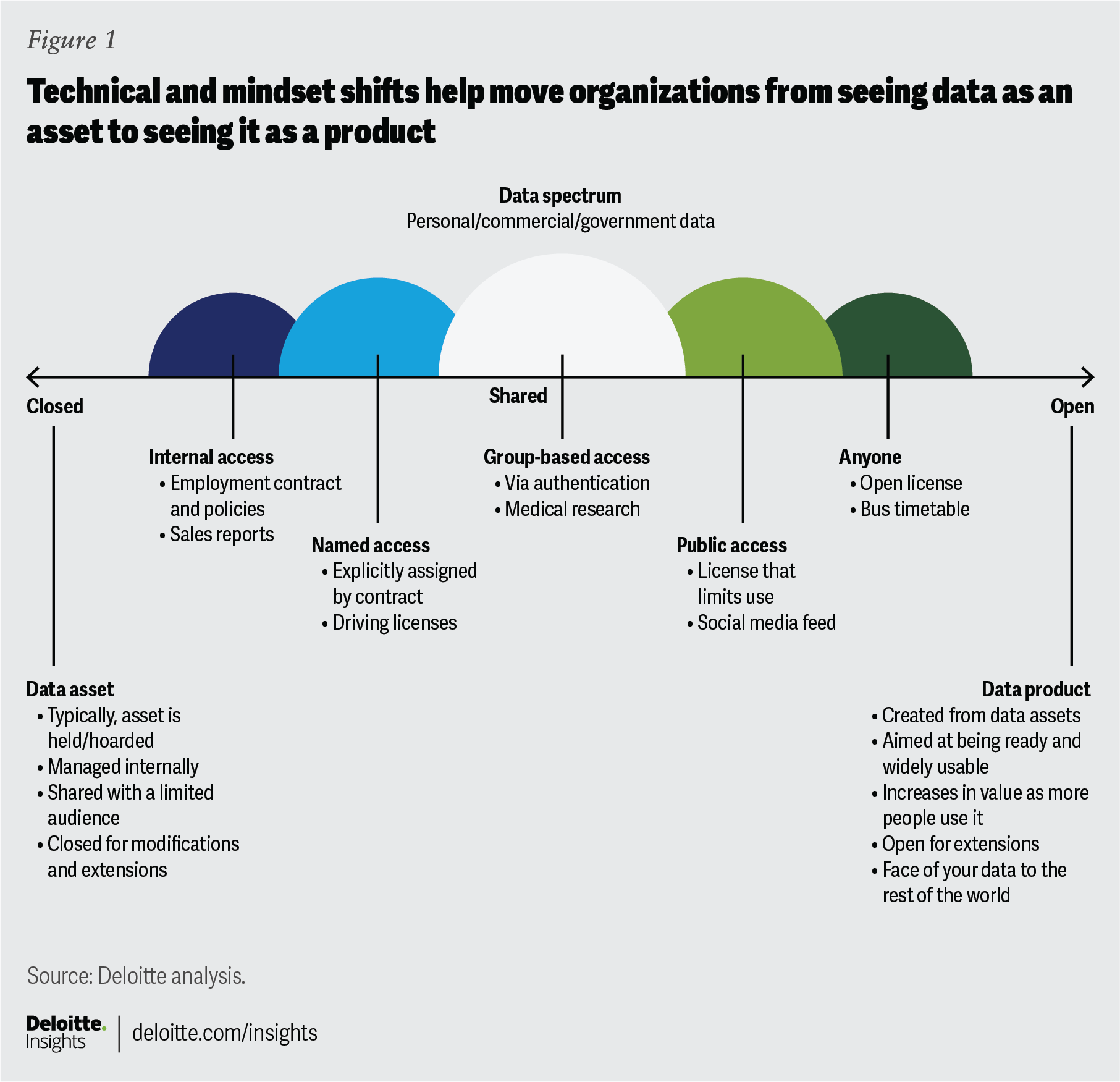

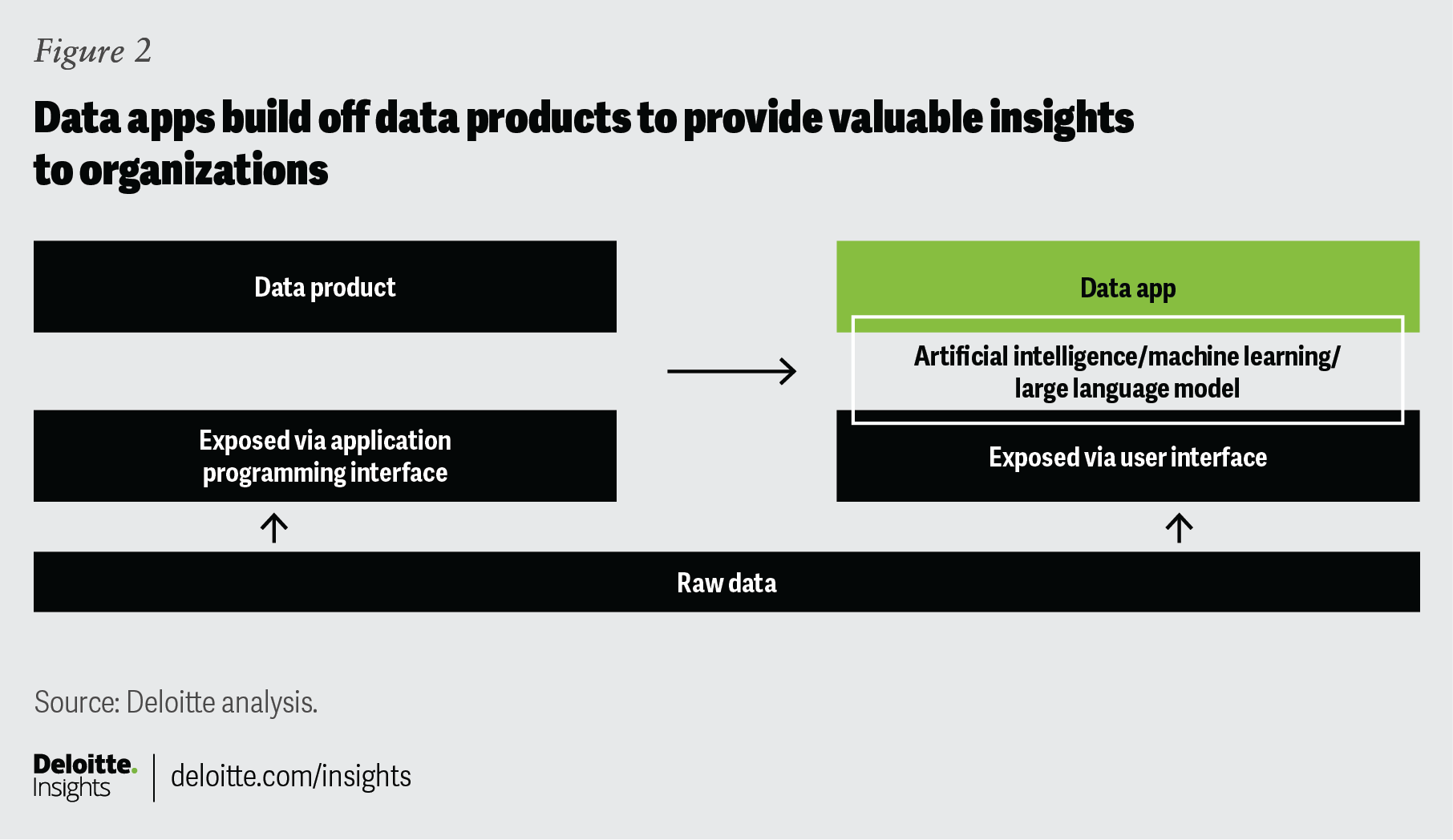

Fundamentally, the shift from data as an asset to data as a product is about making data more open and available. Once data is open and organized in a data product, data apps can be constructed to apply machine learning and expose the data even further via user interfaces. These twin shifts may require changes in both technology and mindset but can unlock significant mission value across the organization.3

Rethinking information for broader use

What does it mean to shift from asset to product? One important element is the rethinking and reorganization of data to achieve mission objectives.

One major change is to begin organizing data by use or application rather than by ownership. Today, many organizations treat data as an asset—a valuable resource usually “owned” by one part of the organization. Even where data isn’t explicitly owned, thinking of data as an asset can lead those who even just control access to data to hoarding information, sharing it sparingly and for the benefit of a department’s existing programs and constituents. As government missions become more digital, data that flows to and from multiple parts of an organization should be analyzed and put to good use to improve performance. CDOs should consider fostering a more open environment, looking to organize data to make it available for potential cross-agency uses. As many private sector examples illustrate,4 wider usage can lead to greater impact. Bringing together multiple open sources so they can be applied to the mission is a foundation of the core of seeing data as a product (figure 1).

Reorganization could begin with something as simple as moving where a database is stored or retagging spreadsheet entries to sort constituents into categories that could be more useful than what a system has used for decades. In other cases, reorganization may be far more dramatic and impactful; it may require shifts to the underlying architecture for organizing, storing, and using data within an organization.

But just reorganizing the data might only be half the story. For data to create value, it also may need to be put to use. These uses are data apps. Data apps are software applications that learn from data by using analytics and deep learning to perform cognitive automation. Their primary function is to automate users’ cognitive function by learning business rules from data.5 In other words, if data products are nouns describing the “things” an organization cares about, then data apps are the verbs turning those nouns into insightful sentences (figure 2).

How data products and data apps can come together to create value for an organization can be seen in the following example. A global consumer bank had a massive data lake. Although it had client identifiers, data was still largely organized by division of the bank, consumer accounts, investments, corporate customers, and so on, so workers struggled to create a list of unique customers. By shifting to a data-product approach, the bank was able to find key fields like credit card or account numbers that could link consumer and investment accounts. This allowed the bank to see the world through their customer’s eyes, not through the eyes of their data structure. They could create data apps that would find insights from that data, such as new opportunities for cross-sales and new revenue.6

It’s not just private companies that are making strides in developing this mindset shift. Governments are increasingly seeing the value of data products and data apps as well. Consider how many cities—even midsized ones—have developed—and keep upgrading—smartphone apps with live-transit timetables tracking each bus and train.7 And agencies routinely update chatbots that quickly and automatically access users’ accounts and offer personalized assistance.8

Creating data products and data apps

Language matters in changing broader attitudes toward data within government. CDOs should help lead that change by changing how they themselves talk about data. The shift to data assets and data apps comes with new technologies and new jargon that can be impenetrable to regular workers. But framing the conversations in terms of what data apps can allow you to do rather than how they work can help reduce the friction of communicating between IT and mission staff. Getting everyone speaking the same language can only help.

Data mesh architecture

In 2019, technology consultant Zhamak Dehghani laid out ways for organizations to change their data architectures to make data more accessible and usable. In trying to escape “a landscape of fragmented silos of inaccessible data,” many organizations turned to massive “data lakes” that help as much of an organization’s data as possible. While this approach could make data more usable than silos, it also had its own problems. There was little incentive for data owners to ensure data cleanliness or accuracy. So, to make data both accessible and usable, Dehghani realized that there needed to be a new approach—an approach that treated data as “ever present, ubiquitous, and distributed.”9

The goal is to move beyond a complex, expansive big-data ecosystem that struggles to offer real-time analytics to an architecture “enabled by a shared and harmonized self-serve data infrastructure.” Dehghani proposed a data architecture with data remaining within its domain but being made accessible by overarching standards and platforms.10 Different domain data sets use data catalog platforms offering discoverability, access control, and governance. And treating data as a product rather than an asset is key. Agency CDOs shouldn’t see technology as a limitation to making the shift—mindset could often be a much bigger issue.11

Data mesh is fundamentally antisilo, aiming to create domain-oriented decentralization of data ownership and architecture, as well as boost convenience and interoperability across domains and multiple data owners. Making information easier to share, especially in the form of data products, should help create more opportunities for value creation.

As with any issues of data-sharing and governance, government agencies face different and perhaps higher stakes for safety and security. Constituent information can be even more sensitive and personal than a commercial organization’s customer information, and often program participation is mandatory.12 When data becomes more widely available or begins passing through more systems or changes hands more often, points of vulnerability can multiply. So, CDOs should aim for data products that are secure and data apps that are streamlined and efficient, giving internal and external customers usable, relevant information without increasing risk.

Increased analytic capabilities, applied to new information availability, are helping agencies create data-driven missions with expanded mandates and impact: For instance, USAID’s “Development data policy” aims to make evidence and information of actionable, qualitative insights available to a larger audience than ever before.13

Getting started

To begin using information to create data products and apps,14 CDOs should assess the feasibility of use cases to begin organizing data by specific use, considering data interoperability across departments and agencies. In considering data architectures, CDOs should look to create a space for data owners to produce and distribute their own domain’s information rather than squeezing disparate domains into an inflexible platform. The focus should be on potential uses of data and how to most effectively get it from the source to the eventual presentation.

To get the organization to think about data as a product, the CDO often plays the key role, as a broker between the data producer and data consumer—defining common terms, alleviating friction between consumers, enabling each data owner’s control and domain independence, driving innovation through the organization, and helping all sides of each potential transaction understand its value. Ultimately, the CDO should act as the glue between people who may need to use data and people who are providing data, even if both parties have trouble breaking free of their traditional roles and patterns. Everyone may not clearly see the pathway to a mindset shift, but it can be important for agencies looking to use data to boost efficiency, broaden mandates, create value, and fulfill mission objectives.