Global risk management survey, 10th edition

Heightened uncertainty signals new challenges ahead

While many organisations continue to enhance their risk management practises worldwide, this year's survey revealed that leaders are focussed on the regulatory impact of recent geopolitical shifts and questioning what's coming next.

Foreword

Dear colleague,

We are pleased to present the 10th edition of Global risk management survey, the latest instalment in Deloitte’s ongoing assessment of the state of risk management in the global financial services industry. The survey findings are based on the responses of 77 financial institutions from around the world and across multiple financial services sectors, representing a total of $13.6 trillion in aggregate assets. We wish to express appreciation to all the survey participants for their time and insights.

Overall, the survey found that leading risk management practises continue to gain wider adoption across the industry.1 Boards of directors are devoting more time and taking a more active role in the oversight of risk management. The chief risk officer (CRO) position has become almost universal and CROs are increasingly reporting directly to the board of directors and the chief executive officer (CEO). Enterprise risk management (ERM) programmes designed to identify and manage risks across the enterprise are now the norm. Almost all respondents consider their institution to be effective in managing traditional risk types such as credit, market and liquidity risk. These and other trends over the course of Deloitte’s Global risk management survey series are summarised below in the section “Evolution of risk management.”

The progress has been undeniable, but in the years ahead risk management is likely to face a different type of challenge. In the years since the global financial crisis, financial institutions have worked hard to address ever-increasing regulatory requirements. In 2017, however, the industry may be reaching an inflection point. After the fundamental reforms of the last several years, there are indications that going forward the trend of ever-broader and more stringent regulatory requirements may slow or actually be reversed in some areas. The US Federal Reserve has eliminated the qualitative review of capital plans and stress testing for large, noncomplex firms; some European regulators and institutions have resisted recent so-called “Basel IV” proposals to establish a capital floor and President Trump has announced steps to review and potentially cut back on requirements implemented by federal agencies under the Dodd-Frank Act.

There is also far more uncertainty than usual over the outlook for economic growth given the United Kingdom’s referendum to leave the European Union (EU); the rise of populist parties in France, Italy and other European countries that oppose membership in the European Union; and President Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and his pledge to renegotiate trade agreements with China and Mexico. While all of these developments could depress growth, there is also the potential for increased business activity resulting from President Trump’s proposals during the campaign to reduce personal and business taxes, launch a major programme of infrastructure investment and cut regulations on businesses.

When it comes to the business environment, the more widespread emergence of fintech firms has substantially raised the level of strategic risk. These start-ups are threatening to disrupt financial sectors and services such as lending, payments, wealth management, and property and casualty products.

Financial institutions are also responding to two major emerging risks. Cybersecurity has become an ever-greater concern with breaches increasing in number and impact. Another area that has received closer attention from regulators is the need for financial institutions to take proactive steps to encourage ethical behaviour among their employees and create a risk-aware culture.

Financial institutions are facing a fiercer battle for talent. The implementation of new and more stringent regulatory requirements has increased the demand for professionals that possess both risk management skills and experience in the financial industry.

The expansion of regulatory requirements over the last several years has led compliance costs to skyrocket and financial institutions are looking to rationalise their processes and use technology applications to create greater efficiencies.

Viewed in combination, these trends mean that effective risk management is becoming increasingly important. In the current uncertain regulatory and business environment, financial institutions should consider taking their risk management programmes in new directions and to a new level to meet the new challenges that lie ahead. At the same time, they will want to develop efficient business processes will be critical to restrain risk management spending in a low-growth and low-interest-rate environment. Most important, they will require agile processes and nimble risk information technology systems that will allow them to respond flexibly to potential changes in the direction of regulatory expectations or from disruption caused by fintech players.

We hope that this overall assessment of risk management at financial institutions around the world provides you with useful insights as you work to further enhance your organisation’s risk management programme.

Sincerely,

Edward T. Hida II, CFA

Risk & capital management leader

Financial services

Deloitte & Touche LLP

Executive summary

THE years since the global financial crisis have seen a wave of regulatory change that increased both the scope and the level of stringency of regulatory requirements. New legislation and regulations have included the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Action (Dodd-Frank Act) in the United States, Basel 2.5 and III, the US Federal Reserve’s Enhanced Prudential Standards (EPS), the European Market Infrastructure Regulation (EMIR) and Solvency II capital standards. In the years since the global financial crisis, financial institutions have had more time to understand the practical implications of these new regulations and what is required to comply.

Today, risk management is becoming even more important; financial institutions confront a variety of trends that have introduced greater uncertainty than before into the future direction of the business and regulatory environment. Economic conditions in many countries continue to be weak, with historically low interest rates. The UK referendum to leave the European Union (Brexit vote), coupled with US President Donald Trump’s pledge to renegotiate trade agreements with China and Mexico, raise the possibility that trade volumes may decline.

The continual increase in regulatory requirements may abate or even be reversed in 2017 as President Trump and others have questioned whether regulatory oversight has gone too far. Strategic risk is increasing as entrepreneurial fintech players are competing with traditional firms in many sectors. The rapidly changing environment suggests that risk management programmes may need to increase their ability to anticipate and respond flexibly to new regulatory and business developments and to emerging risks, for example, by employing predictive analytics tools.

Deloitte’s Global risk management survey, 10th edition assesses the industry’s risk management practises and the challenges it faces in this turbulent period. The survey was conducted in the second half of 2016—after the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom but before the US presidential election—and includes responses from 77 financial services institutions around the world that conduct business in a range of financial sections and with aggregate assets of $13.6 trillion.

— Chief risk officer, large diversified financial services company

Key findings

Cybersecurity. Only 42 per cent of respondents considered their institution to be extremely or very effective in managing cybersecurity risk. Yet, cybersecurity is the risk type that respondents most often ranked among the top three that would increase in importance for their institution over the next two years (41 per cent). In recognition of the broad senior management and board awareness of cybersecurity risks, most respondents did not report challenges in securing funding or in communicating with senior management or the board. However, many boards of directors face the challenge of securing sufficient technical expertise to oversee the management of cybersecurity risk. The issues cited most often as extremely or very challenging were hiring or acquiring skilled cybersecurity talent (58 per cent) and getting actionable, near-real-time threat intelligence (57 per cent).

Institutions less effective at managing newer risk types. Roughly 80 per cent or more of respondents said their institution is extremely or very effective at managing traditional risk types such as liquidity (84 per cent), underwriting/reserving (83 per cent), credit (83 per cent), asset and liability (82 per cent), investment (80 per cent) and market (79 per cent). Newer risk types present more challenges and fewer respondents rated their institution highly at managing model (40 per cent), third party (37 per cent) and data integrity (32 per cent). Given the heightened geopolitical uncertainty and change during the period when the survey was conducted, as evidenced by the UK Brexit referendum and the discussion of US trade policies during the US presidential campaign, it is notable that the percentage of respondents who considered their institution to be extremely or very effective at managing geopolitical risk was only 28 per cent, a sharp drop from 47 per cent in 2014.

Significant challenges posed by risk data and IT systems. Few respondents considered their institution to be extremely or very effective in any aspect of risk data strategy and management, such as data governance (26 per cent), data marts/warehouses (26 per cent) and data standards (25 per cent). Even fewer respondents rated their institution this highly in other areas including data sourcing strategy (16 per cent), data process architecture/workflow logic (18 per cent) and data controls/checks (18 per cent). Many respondents also had significant concerns about the agility of their institution’s risk management information technology systems. Roughly half of the respondents were extremely or very concerned about risk technology adaptability to changing regulatory requirements (52 per cent), legacy systems and antiquated architecture or end-of-life systems (51 per cent), inability to respond to time sensitive and ad-hoc requests (49 per cent) and lack of flexibility to extend the current systems (48 per cent).

Battle for risk management talent. With the increase in regulatory requirements, there has been greater competition for professionals with risk management skills and experience. Seventy per cent of respondents said attracting and retaining risk management professionals with required skills would be an extremely or very high priority for their institution over the next two years, while 54 per cent said the same about attracting and retaining business unit professionals with required risk management skills. Since cybersecurity is a growing concern across all industries, the competition is especially intense for professionals with expertise in this area. As noted above, when asked how challenging various issues in managing cybersecurity risk were, the item cited third most often as extremely or very challenging was hiring or acquiring skilled cybersecurity talent (58 per cent).

— Chief risk officer, large diversified financial services company

Greater use of stress testing. Regulators are increasingly using stress tests as a tool to assess capital adequacy and liquidity, and 83 per cent of institutions reported using capital stress testing and the same percentage reported using liquidity stress testing. For both types of stress tests, more than 90 per cent of institutions reported using it for reporting to the board, reporting to senior management and for meeting regulatory requirements and expectations. For both capital and liquidity stress tests, the two issues most often rated as extremely or very challenging concern IT systems and data: stress testing IT platform (66 per cent for capital stress testing and 45 per cent for liquidity stress testing) and data quality and management for stress testing calculations (52 per cent for capital stress testing and 33 per cent for liquidity stress testing).

Increased importance and cost of compliance. Thirty-six per cent of respondents cited regulatory/compliance risk as among the three risk types that will increase the most in importance for their business over the next two years, the risk named second most often. Seventy-nine per cent of respondents said that regulatory reform had resulted in an increased cost of compliance in the jurisdictions where it operates and more than half the respondents said they were extremely or very concerned about tighter standards or regulations that will raise the cost of doing existing business (59 per cent) and the growing cost of required documentation and evidence of programme compliance (56 per cent).

Increasing oversight by boards of directors. Eighty-six per cent of respondents said their board of directors is devoting more time to the oversight of risk management than it did two years ago, including 44 per cent who said it is devoting considerably more time. The most common risk management responsibilities of boards of directors are review and approve overall risk management policy and/or ERM framework (93 per cent), monitor risk appetite utilisation including financial and nonfinancial risk (89 per cent), assess capital adequacy (89 per cent) and monitor new and emerging risks (81 per cent). However, there is more work to do in instilling a risk culture, where no more than roughly two-thirds of respondents cited as board responsibilities help establish and embed the risk culture of the enterprise (67 per cent) or review incentive compensation plans to consider alignment of risks with rewards (55 per cent).

CRO position almost universal. Ninety-two per cent of institutions reported having a CRO position or equivalent, yet there remains significant room for improvement in the role. The CRO does not always report to the board of directors (52 per cent), which provides important benefits and is generally a regulatory expectation. Although the CRO meets regularly with the board of directors at 90 per cent of institutions, many fewer institutions (53 per cent) reported that the CRO meets with the board in executive sessions. The CRO is the highest level of management responsible for risk management at about half of the institutions (48 per cent), with other institutions placing this responsibility with the CEO (27 per cent), the executive-level risk committee (16 per cent), or the chief financial officer (CFO) (4 per cent). The most common responsibilities for the CRO were to develop and implement the risk management framework, methodologies, standards, policies and limits (94 per cent), identify new and emerging risks (94 per cent) and develop risk information reporting mechanisms (94 per cent). Despite the increasing importance of strategic risk and the related need for risk management of business strategy and decisions, fewer respondents said the CRO has the responsibility to provide input into business strategy development and the periodic assessment of the plan (65 per cent), participate in day-to-day business decisions that impact the risk profile (63 per cent), or approve new business or products (58 per cent). And while regulators have placed greater focus on the importance of conduct and culture, review compensation plan to assess its impact on risk appetite and culture was identified as a responsibility by 54 per cent of the respondents.

Steady increase in the adoption of ERM. Seventy-three per cent of institutions reported having an ERM programme, up from 69 per cent in 2014 and more than double the 35 per cent in 2006. In addition, another 13 per cent of institutions said they are currently implementing an ERM programme and 6 per cent said they plan to create one. An institution's ERM framework and/or policy is a fundamental document that should be approved by the board of directors and 91 per cent of institutions said this had occurred, up from 78 per cent in 2014. Two of the issues frequently cited as extremely or very high priorities for their risk management programmes over the next two years concerned IT systems and data: enhancing the quality, availability and timeliness of risk data (72 per cent). Another issue considered to be an extremely or very high priority by a substantial majority of respondents was of risk management

Over the 20 years that Deloitte has been conducting its Global risk management survey series, the financial services industry has become more complex with the evolution of financial sectors, the increased size of financial institutions, the global interconnectedness of firms, and the introduction of new products and services. At the same time, regulatory requirements and expectations for risk management have broadened to cover a wider range of issues and also become more stringent, especially in the years since the global financial crisis. Deloitte's survey series has assessed how institutions have responded to these developments, the substantial progress that has occurred in the maturity of risk management programmes and their challenges. In general over this period, risk management programmes have become almost universally adopted and programmes now have expanded capabilities. Boards of directors are more involved in risk management and more institutions employ a senior-level CRO position. The following are some of the key areas where the survey series has documented an increasing maturity in risk management programmes.

More active board oversight. In 2016, 93 per cent of respondents said their board of directors reviews and approves the overall risk management policy and/or ERM framework, an increase from 81 per cent in 2012.

More use of board risk committees. It is a regulatory expectation that boards of directors establish a risk committee with the primary responsibility for risk oversight. The use of a board risk committee has become more widespread, increasing from 43 per cent of institutions in 2012 to 63 per cent in 2016, although there is clearly room for further adoption (figure 1).

Increased adoption of CRO position. Over the years, there has been a continual increase in the percentage of institutions with a CRO position or equivalent, from 65 per cent in 2002 to become almost universal with 92 per cent in 2016 (figure 2). At the same time, the CRO is a more senior-level position reporting to higher levels of the organisation. In 2016, 75 per cent of respondents said the CRO reports to the CEO, a substantial increase from just 32 per cent in 2002. Similarly, the CRO more often directly reports to the board of directors—at 52 per cent of institutions in 2016 up from 32 per cent in 2002. Seventy-seven per cent of institutions reported that the CRO is a member of the executive management committee, an increase from 58 per cent in 2010.

Wider set of responsibilities for the CRO. Over time, the CRO and the independent risk management programme have been given a wider set of responsibilities at many institutions. For example, 92 per cent of respondents said a responsibility of the CRO was to assist in developing and documenting the enterprise-level risk appetite statement compared with 72 per cent in 2008. Similarly, 76 per cent said a CRO responsibility is to assess capital adequacy, while this was the case at 54 per cent of the institutions in 2006.

Widespread adoption of ERM programme. The adoption of ERM programmes has more than doubled, from 35 perc ent in 2006 to 73 per cent in 2016 (figure 3). The implementation of ERM programmes moved upwards in 2010, which was likely due to post-financial crisis focus on enhancing risk management.

While there has been considerable progress in the continued development and maturation of risk management programmes, there remains considerable work to do. The specific areas where risk management programmes need to further enhance their capabilities and effectiveness, and the likely future challenges, are detailed in the body of this report.

Introduction : Economic and business environment

Deloitte’s Global risk management survey, 10th edition was conducted as a variety of trends were having a dramatic impact on the financial services industry, in some cases with their future direction difficult to predict.

Low-revenue environment

Financial institutions are struggling to generate returns in an environment of historically low interest rates and slow economic growth, coupled with increasing regulatory requirements. The weak economic conditions provide less opportunity to generate revenue and may also increase credit risk. The result has been a greater focus on controlling the cost of risk management programmes, with institutions looking to increase efficiency by creating centres of excellence and by rationalising and consolidating processes, especially in the second line of defence (the independent risk management function).

Global growth in 2016 was expected to be 3.1 per cent and then increase to 3.4 per cent in 2017, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2 The outlook was more modest for developed economies with growth projected to be 1.6 per cent in 2016 and 1.8 per cent in 2017.

The US economy was expected to grow 1.6 per cent in 2016 and 2.2 per cent in 2017, while the Euro area was expected to have growth of 1.7 per cent and 1.5 per cent in these two years. In the wake of the Brexit vote, the United Kingdom was projected to see its growth rate slow from 1.8 per cent in 2016 to 1.1 per cent in 2017. In Japan, growth was projected to be just 0.5 per cent in 2016 and 0.5 per cent in 2017. GDP growth in China was predicted to be 6.6 per cent in 2016 but slow somewhat to 6.2 per cent in 2017.

Weak economic conditions have created challenges for financial institutions. Return on average equity for US banks was 9.0 per cent in the third quarter of 2016, compared to 12.2 per cent in 2006-2007. 3 The performance of European banks was even weaker, with average return on equity of 5.9 per cent in the first quarter of 2016, which was below the cost of equity. 4 An analysis by the IMF found that banks in the European Union were earning less than half of their average 2004–2006 profits.

The IMF found that more than one-quarter of the banks in advanced economies, with about $11.7 trillion in assets, would remain weak and face continued structural challenges even if a cyclical recovery occurred, with the greatest problems at institutions in Europe and Japan. 5 Similarly, the ongoing period of low interest rates could call into question the solvency of many insurers.

China has been undergoing a transition towards an economy that is more based on consumption and services and less dependent on manufacturing activity and investment. In addition, it has moved to rely more on markets to set interest rates and exchange rates. However, concerns remain over its rapid increase in debt, including a significant fraction considered at risk, often to state-owned enterprises. 6

Increasing regulatory requirements for capital and liquidity

Capital requirements include Basel 2.5 and III, the US Federal Reserve’s Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) and Dodd-Frank Act Stress Tests (DFAST). From mid-2011 through the end of 2015, 91 leading banks around the world have increased their common equity by $1.5 trillion, with the ratio of equity to risk-weighted assets rising from 7.1 per cent to 11.8 per cent. This puts the equity capital ratios of banks substantially above the Basel III minimum of 4.5 per cent. 7

There have been wide variations across banks in the calculations of required capital due to each bank’s choice of internal models, which raises questions about transparency and whether some calculations appropriately reflect underlying risk. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (Basel Committee) has issued several proposals (the so-called “Basel IV” proposals) to introduce enhanced standardised approaches to eliminate or reduce the role of internal models in calculating minimum capital charges and establish a minimum capital floor. The proposed changes could lead risk-weighted assets to rise by an average of 18 per cent to 30 per cent, requiring more capital, according to an analysis by Morgan Stanley. 8

However, there has been some resistance to establishing a capital floor from European banks and officials who believe this would require European banks holding large amounts of low-risk assets such as mortgages to hold more capital, putting them at a competitive disadvantage. 9 Concerns have also been expressed by the Japan Financial Services Agency (JFSA) and the Reserve Bank of India. 10

US institutions and other global banks operating in the European Union also face a new proposal that would require their EU operations to have separate intermediate holding companies that will be subject to consolidated capital and liquidity requirements.

In the United States, the Federal Reserve has eliminated the qualitative examination portion of its annual Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) for institutions with less than $250 billion in assets, $10 billion in foreign exposure and $75 billion in nonbank assets. The Federal Reserve has also indicated it will issue a proposed rule to effectively embed stress-test results into current capital requirement buffers and implement the surcharge buffer for global systemically important banks (GSIBs).

Among insurers, institutions active in Europe must comply with Solvency II capital requirements, which took effect on 1 January 2016. US insurers must comply with similar Own Risk Solvency Assessment (ORSA) capital requirements put in place by state regulators. US companies subject to ORSA are required to submit an annual filing to their state department of insurance detailing the company’s own assessment of its risk profile, the processes in place to manage risks, the potential impact of those risks and a view on solvency. 11 In January 2017, the Treasury Department, acting through the Federal Insurance Office and the Office of the US Trade Representative, announced the successful completion of negotiations for a “covered” agreement with the European Union on prudential measures regarding insurance and reinsurance. 12 Under the agreement, which covers three areas of insurance oversight—reinsurance, group supervision and the exchange of insurance information between supervisors—US and EU insurers operating in the other market will only be subject to oversight by the supervisors in their home jurisdiction. 13

Financial institutions have also faced an increasing set of liquidity requirements in the years since the global financial crisis. Liquidity requirements introduced or in the process of implementation include the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) and the net stable funding ratio (NSFR) introduced in Basel III. Under the enhanced prudential standards (EPS), the US Federal Reserve recently implemented additional liquidity reporting requirements for both US and foreign banks operating in the United States with total consolidated assets of $50 billion or more. These requirements impact treasury, risk and operations, particularly around risk management, cash flow forecasting, contingency funding planning, limit setting, stress testing, liquidity buffer sizing and management, and governance, among other areas. 14 In addition, the Federal Reserve 2052a reporting requirement places an additional emphasis providing detailed information to allow the Federal Reserve to monitor the overall liquidity profile of institutions. 15 These and other liquidity requirements are still being finalised or fully implemented and their implications and linkages are still being studied.

Uncertain outlook for regulatory requirements

There are significant questions regarding whether the continual ratcheting up of regulatory requirements since the global financial crisis will continue. As noted above, some European regulators and financial institutions are pushing back on Basel plans to implement a regulatory capital floor. In the United States, President Trump criticised the Dodd-Frank Act during the presidential campaign and in February 2017 issued an executive order instructing the Treasury Department to review financial regulations to determine whether they are consistent with the administration’s goals such as enhancing the competitiveness of American companies. 16 There have also been various proposals by the US Congress to scale back or eliminate the Dodd-Frank Act that are expected to be refined and re-introduced as legislation in 2017. Although repealing the Dodd-Frank Act would likely not be possible without some Democratic support (since new legislation would require 60 votes in the Senate to overcome a filibuster and Republicans only have a 52-48 majority), the Trump administration could still make substantial regulatory changes through other means. These include attaching policy riders to appropriation bills or through the budget reconcilliation process (which only requires a simple majority in the Senate); changes to agency rules or regulatory guidance within the limitations of the governing laws; and changes to the approaches to rulemaking, supervision and enforcement at the federal level.

President Trump will also make a number of appointments to regulatory bodies that have substantial discretionary authority to change regulatory requirements, such as capital and liquidity requirements, including the Federal Reserve, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the Financial Stability Oversight Council.

In February 2017, President Trump signed a memorandum instructing the Department of Labour to conduct an updated legal and economic analysis of the proposed Conflict of Interest rule, which had been slated for implementation in April 2017 and rescind or revise the rule if it is found to have adverse impacts. 17 Among the other rules and guidance that fall under the discretionary authority of the associated agencies are the requirements of the CCAR/DFAST programmes and designations of nonbank financial institutions as systemically important.

In another kind of regulatory uncertainty, institutions occasionally receive unexpected regulatory feedback. In their most recent review, the Federal Reserve and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) determined that certain resolution plans submitted by the eight GSIBs were “not credible or would not facilitate an orderly resolution” under the US Bankruptcy Code. The agencies provided explicit guidance regarding expectations for the next full resolution plan submissions due by

July 1, 2017. The Federal Reserve also extended the resolution plan submission deadline for other filers.

— Chief risk officer, large financial services company

Geopolitical uncertainty

In addition to the potential impact on financial regulations, the political developments in major western economies in 2016 have ushered in a period of geopolitical uncertainty, with potentially far-reaching implications for the future of globalisation and trade.

The Brexit vote for the United Kingdom to leave the European Union could have substantial impacts on financial institutions, even those that do not have operations in this region, due to a slowdown in economic activity. In January 2017, UK Prime Minister Theresa May indicated the intention to negotiate a clean break with the European Union.18 It is expected that there may be more trade friction between the United Kingdom and the European Union after separation, less free movement of people across these borders, and a more complex and uncertain regulatory environment. Among other impacts, the uncertainty may make it more difficult to predict returns on equity with confidence from UK and EU operations, earnings could decline due to weaker economic activity in Europe and regulatory standards in the United Kingdom could diverge from those in the European Union.

One consequence of Brexit is that UK-based firms will lose the “passport” ability to distribute their products across the European Union, which is important to the United Kingdom’s role as a financial centre. The potential remains that financial firms may be able to continue to distribute some products across the European Union where the UK regulatory regime is considered to be “equivalent.”19 If firms with UK-based operations lose the ability to distribute their products across the EU market, significant restructuring and relocation may be required across Europe, with firms needing to decide if the related expenditures and disruptions fit their strategic plans.

These impacts on trade would be heightened if other countries join the United Kingdom in deciding to leave the European Union. Populist parties that oppose EU membership have gained ground in France, the Netherlands, Austria and Italy. In 2017, France will hold a presidential election, in which the National Front, which opposes EU membership, is one of the leading parties. In the wake of the rejection by Italian voters of a constitutional reform parcel, Italy may also hold an election in 2017, where the populist Five Star Movement that opposes Italy’s membership in the European Union has been gaining ground.

In his first days in office, President Trump signed an executive order withdrawing the United States from the TPP, while during the presidential campaign he supported renegotiating trade agreements with Mexico and China and proposed placing a tariff on the goods of US companies that move operations outside the country.

Global trade in goods and services is far below its historical pace, having grown just 3 per cent since 2012, less than half the average rate over the previous three decades, which may be the result of the simultaneous slowdown in economic growth across both developed and emerging economies. Another factor is the slowdown in China’s economy and the fact that it is coming to rely more on consumption and less on manufacturing investment, which has reduced Chinese imports of commodities and other goods. There had been a rapid increase in Chinese imports over the previous decade and China now is among the top importers for more than 100 countries that account for roughly 80 per cent of world GDP.20 With the possibility that additional countries may leave the European Union and that the United States may renegotiate its trade agreements, it remains to be seen whether additional trade restrictions will be put in place that could further slow global trade and what impact this may have on economic growth.

Focus on role of business in risk management

Institutions are working to more effectively and efficiently implement the three lines of defence risk model governance framework. Under the model, business units (the first line of defence) manage the risks in their areas in order to increase accountability, while the risk management programme (second line of defence) is responsible for oversight and challenge. Placing primary responsibility for managing risk in the business units as the first line of defence increases the effectiveness of risk management by leveraging their knowledge of their business activities and operations, while also helping to instil a culture of owning inherent risk in the business.

While this model is conceptually simple and appealing, over time the actual practises implemented have become inefficient, with redundancies and in some cases ineffective areas due to gaps. As a result, institutions are seeking to clearly define the roles and responsibilities of each line, ensure their business units carry out their risk management responsibilities, and align business activities with the institution’s risk appetite and risk management policies. At the same time, institutions are looking to simplify and rationalise the risk management processes across the lines of defence.

Growing cybersecurity risk

Improving management of cybersecurity risks has been an increasing concern of financial services institutions and has also been receiving greater attention from regulators and policy setters. There is a wide range of types of cyber risks including attacks on operating systems; locking users out of their computers and data; theft or corruption of data and systems; and release of confidential data, intellectual property, or corporate strategy.

Banks, securities companies, investment management firms, insurers and payment and clearing systems are prime targets for cybercriminals looking to steal money or data, or compromise critical infrastructure, spurred by the large amounts of money involved and the increased use of online and mobile banking. Cyberattacks increased by 50 per cent in the second quarter of 2016 compared to the second quarter of 2015 and the number of cyberattacks against financial institutions is estimated to be four times greater than against companies in other industries.21 A study in the first quarter of 2016 found that there had been a 40 per cent increase in cyberattacks targeting financial institutions.22

In 2016, the Federal Reserve, the FDIC and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) issued an advanced notice of proposed rulemaking regarding enhanced cyber risk management and resilience standards for large banks, which may lead to a more formal proposed rule in 2017. The regulators in the European Union are expected to follow suit. In insurance, in 2015 the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) issued a document setting out principles for effective cybersecurity and cybersecurity has now been integrated into insurance regulatory examinations. Also in the United States, the New York State Department of Financial Services (DFS) proposed prescriptive cybersecurity requirements for banks and insurance companies, which it describes as a “first-in-the-nation cybersecurity regulation.”23

Managing cyberthreats is also a priority for regulators in Asia Pacific. In May 2016, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) launched the Cybersecurity Fortification Initiative, which includes a mandatory self-assessment of cybersecurity risks faced by financial services institutions, simulation exercises, a professional development programem and the launch of a Cyber Intelligence Sharing Platform.24 The Cybersecurity Law of China, which will take effect on June 1, 2017, will impose obligations on “critical information infrastructure operators” and “network operators” to, among other requirements, keep personal information and important business data collected or generated in China within China, have appropriately qualified dedicated cybersecurity staff, report incidents to data owners and authorities, and conduct annual reviews and assessments of cybersecurity threats. Regulators in Japan, Singapore and Australia are also focussing on the need for institutions to implement cybersecurity frameworks, predict potential threat scenarios, regularly test security measures and address any weaknesses identified.25

Cyber risk is top of mind for everyone and probably more the question of when, not if something hits.

— Chief risk officer, large diversified financial services company

Central role of conduct and culture

Encouraging ethical conduct among employees and instilling a risk management culture throughout the organisation has been a focus of regulators since the global financial crisis. Recently, there have been notable instances of inappropriate behaviour at major financial institutions, both in retail markets and wholesale markets, which could lead regulators to give even more attention than before to conduct and culture. Institutions need to address instances of poor culture, lack of accountability and misaligned incentive compensation policies, or face the potential for intervention by regulatory authorities.

The European Banking Authority (EBA) has revised guidelines on internal governance, placing more emphasis on conduct, culture and conflicts of interest. EBA’s stress tests in 2016 assessed an additional €71 billion in losses under an adverse conduct risk scenario, while the Bank of England’s stress tests identified £40 billion of additional conduct risk costs for the seven banks participating.

European insurers should prepare for the implementation of the Insurance Distribution Directive standards on product governance, disclosures and conflicts of interest. The European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) has made consumer protection a strategic priority for 2017.

In the United States, the Federal Reserve has placed an emphasis on the importance of financial institutions encouraging ethical behaviour by their employees through hiring, incentives/compensation and setting an appropriate ‘tone at the top.’ The Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY) has held three conferences on culture and behaviour in the financial services industry and continues to stress the importance of the issues. US regulators have twice proposed rules on incentive compensation.

Australian regulators are also placing a heavy focus on conduct and culture in the financial services industry. The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) released an information paper in late 2016 that assessed risk culture within the industry as being at a very early stage of maturity, called for a deeper analysis and understanding of risk culture across the entire sector and set out a detailed regulatory work plan that will include pilot reviews and a stocktake of remuneration practises.26

Hong Kong’s Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) recently articulated its expectations with regard to senior management accountability, including the designation of fit and proper individuals to be “managers-in-charge” of core functions and a requirement to submit management structure information and organisational charts.27 The increased focus on this area has made it important for financial institutions to have a formal programme for risk management conduct and culture with appropriate resources. To address the complex of conduct, culture and ethics management, institutions may need to redouble their efforts to align their business practises and incentives/compensation with risk management and integrate risk management considerations throughout day-to-day business practises. Institutions can benefit from employing a risk control self-assessment (RCSA) process in these areas so that management and staff at all levels identify and evaluate the conduct and culture risks facing the institution and the effectiveness of the associated controls. Other institutions have improved their governance and oversight over key business areas that impact conduct. Some institutions are using predictive analytics tools to identify employee behaviour patterns that warrant further investigation.

This is a tricky area because the whole conduct risk topic itself is emerging and there's no established model as to how to get this right. We've created a separate area within the second line risk function to oversee conduct risk. We have focussed on our risk appetite for conduct risk, our risk management framework for conduct risk and making sure that that all is aligned with the board's expectations.

— Chief risk officer, large financial services company

Fintech disruption

Another source of strategic risk is the more widespread emergence of fintech start-ups, which leverage technology capabilities to compete with traditional banks, investment management firms and insurers in such areas as loans, payment products, wealth management, and property and casualty insurance. Although still a small segment of the market, fintech firms are expanding at a rapid clip. The investment in fintech has grown from $1.8 billion in 2010 to $19 billion in 2015 and in 2015, Goldman Sachs estimated the market to be worth $4.7 trillion.28 Fintech firms have been able to innovate at a faster pace than traditional institutions, for example, creating loan origination platforms that pull information directly from customer tax records and other financial providers, resulting in a faster, cheaper, less burdensome and yet more accurate process.

Regulators around the world are examining the impact of fintech on financial regulation. The US OCC announced in December 2016 that it would develop a process for issuing limited special-purpose national bank charters for fintech firms and subject them to prudential supervision.

In Europe, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) is monitoring the potential risks and benefits to financial stability of fintech, with a particular focus on distributed ledger technologies (including blockchain), peer-to-peer lending and artificial intelligence.29 The European Commission established an internal task force on financial technology and plans to produce policy recommendations during 2017.30 In the United Kingdom, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has launched a “call-for-input” on crowdfunding, indicating its intention to consider rule changes on the risks in the sector, including the mismatch between the maturity of the loans and the promises of liquidity made to investors.31

Asia-Pacific regulators have launched a range of initiatives to nurture and manage the growth of fintech in the region. Many jurisdictions have taken a “regulatory sandbox” approach that allows fintech firms to carry out their activities in a more relaxed regulatory environment (for example, Australia, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Singapore and South Korea). The Monetary Authority of Singapore is a leader in the region and has outlined various innovation initiatives including regulatory sandbox guidelines, plans to consult on algorithms for robo-advisers, establishing a national “know-your-customer” utility and partnering with R3 to develop blockchain.32 In December 2016, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) issued a licencing exemption for fintech firms that it described as “a world first.”33

Traditional financial institutions are also partnering with fintech firms. For example, in 2015, JPMorgan Chase announced that it would make small business loans through OnDeck Capital, a fintech lending platform.34 Other financial institutions are seeking to adopt the entrepreneurial ways of the fintech firms within their own organisations, for example, by creating online wealth management applications to compete with the new fintech players.

To respond to the shifting business environment brought by fintech and other disrupters, it will be important to have robust strategic risk programmes and some institutions may need to conduct their identification and response planning for strategic risks more frequently. These programmes may also need to develop a new mind-set that considers the potential for a greater degree of disruption than may have been seriously considered in the past. The goal should be to focus on the ability to maintain stable earnings and survive potential disruption scenarios.

Ultimately, I think fintech will merge with the banking industry. That could be both beneficial and detrimental to existing players. I think there's an emerging realisation that fintech will bring an awful lot of competition to the banking industry.

— Chief risk officer, large financial services company

About the survey

This report presents the noteworthy findings from the 10th edition of Deloitte's ongoing assessment of risk management practises in the global financial services industry. The survey gathered the views of CROs or their equivalents at 77 financial services institutions across the world and was conducted from July to October 2016.

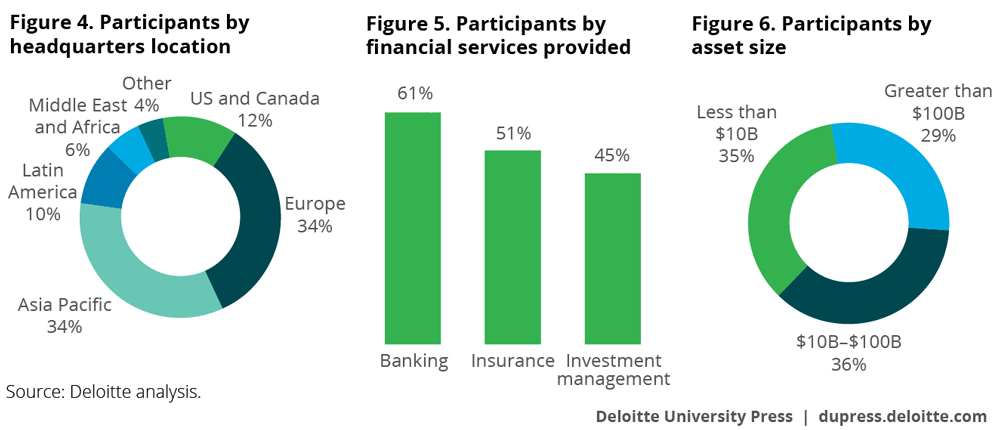

The institutions participating in the survey represent the major economic regions of the world, with most institutions headquartered in the United States/Canada, Europe, Asia Pacific, or Latin America (figure 4). Most of the survey participants are multinational institutions, with 61 per cent having operations outside their home country.

The participating companies provide a range of financial services, including banking (61 per cent), insurance (51 per cent) and investment management (45 per cent) (figure 5). 35

The institutions have total combined assets of $13.6 trillion and represent a range of asset sizes (figure 6). Institutions that provide asset management services represent a total of $6.5 trillion in assets under management.

Where relevant, the report compares the results from the current survey with those from earlier surveys in this ongoing series.

Analysis by asset size

In this report, selected survey results are analysed by the asset size of participating institutions using the following definitions:

- Small institutions—total assets of less than £8 billion

- Mid-size institutions—total assets of £8 billion to less than £80 billion

- Large institutions—total assets of £80 billion or more

Risk governance

Role of the board of directors

Regulators expect a financial institution’s board of directors to play a fundamental role in providing oversight of the risk management programme. The Basel Committee has issued principles specifying that a bank’s board of directors should have overall responsibility for risk management and that a bank should have an effective independent risk management function.36 The EPS rule issued by the Federal Reserve in March 2014 requires that US publicly traded banks with consolidated assets of $10 billion or more have a risk committee of the board of directors chaired by an independent director.37 For US banks with consolidated assets of $50 billion or more, EPS requires that the risk committee must be a stand-alone committee of the board that meets at least quarterly and has at least one independent director knowledgeable of risk management in large, complex banks.38 The US OCC has issued standards requiring large banks to have a board-approved risk-governance framework. For US insurers, in 2014 the NAIC approved a framework for adoption by the state insurance commissioners that requires insurers to file an annual disclosure about their corporate governance practises including the policies and practises of their board of directors.39

In Australia, APRA Prudential Standard CPS 220 Risk Management sets out comprehensive requirements for regulated institutions (for example, banks and insurers). These include stipulations that boards ensure there is a risk management framework for addressing material risks, that the framework include strategic and business planning, and that there is a clearly articulated risk appetite statement that is actively developed and reviewed by the board and communicated appropriately throughout the business operations. Additional requirements are that the regulated institutions have a risk management function, a separate board risk committee, a designated CRO who reports directly to the CEO and a sound risk management culture that includes ongoing risk education and processes to ensure behaviour is monitored and managed within the risk appetite.40

Boards of directors are expected to provide active oversight including approving the risk management framework and risk appetite. Rather than merely receiving periodic briefings, they should be prepared to challenge management decisions and recommendations where appropriate.

Given the increased scope and intensity of regulatory requirements, coupled with a volatile economic environment, most respondents reported that their board of directors is devoting more time to the oversight of risk management compared to two years ago. Forty-four per cent of respondents said their board spends considerably more time overseeing risk management than it did two years ago, while 42 per cent said it spends somewhat more time.

Respondents at banks were more likely to report their board of directors is spending considerably more time on risk management than it did two years ago (57 per cent) than those at investment management firms (43 per cent) and insurance companies (44 per cent). This is not surprising given the pace and scope of changing regulatory requirements and guidance in the banking sector, a large part of which either is focussed specifically on risk management or else has large effects on risk management.

Boards of directors and their risk committees, have a wide range of risk management responsibilities. A number of traditional risk management functions are responsibilities of boards at almost all institutions including review and approve overall risk management policy and/or ERM framework (93 per cent), monitor risk appetite utilisation including financial and nonfinancial risk (89 per cent), assess capital adequacy (89 per cent), and monitor new and emerging risks (81 per cent) (figure 7).

On the other hand, there is room for improvement at many institutions on a number of issues that have recently received attention. Strategic decisions can have a substantial impact on an institution’s risk profile and one might have expected that more than about two-thirds of institutions would say their board’s activities include review corporate strategy for alignment with the risk profile of the organisation (68 per cent). And while regulators have recently placed greater focus on the important role that culture plays in effective risk management, the board oversight activities at many institutions did not include help establish and embed the risk culture of the enterprise (67 per cent) or review incentive compensation plans to consider alignment of risks with rewards (55 per cent).

The important change that we worked on is streamlining and optimising the materials the board gets and moving away from pure reporting to the board towards a substantive discussion of the issues.

— Chief risk officer, large diversified financial services company

Board risk committees

Placing oversight responsibility for risk management with a board risk committee is a general regulatory expectation and has come to be seen as a leading practise. The Basel Committee issued guidance in 2010 that stressed the importance of a board-level risk committee, especially for large banks and internationally active banks and revised guidance in 2015 specifying the appropriate role of the risk committee.41 As noted above, the EPS issued by the Federal Reserve establishes certain requirements for US banks to have a risk committee of the board of directors, with some requirements phased in based on size of institution.

Sixty-three per cent of institutions reported they have a risk committee of the board of directors with primary responsibility for risk oversight, up from 51 per cent in 2014. As a result of the ascendance of the board risk committee, only 16 per cent said the full board has primary responsibility, down from 23 per cent in the prior survey. Some respondents said oversight was a combined responsibility of the board audit and risk committees (8 per cent) or other board committees (9 per cent).

Placing primary responsibility in a board risk committee is much more common in the United States/Canada (89 per cent, up from 61 per cent in 2014), than in Europe (65 per cent), Asia Pacific (52 per cent), or Latin America (63 per cent). This may be a response to the requirements of the Federal Reserve’s EPS and OCC’s heightened standards regarding board risk committees.

A prominent role for board risk committees is more common at banks (74 per cent compared to 56 per cent in 2014), although it also rose at investment management firms (65 per cent up from 44 per cent) and insurers (61 per cent up from 49 per cent).

As noted, there has been a trend for regulators to require that financial institutions include independent directors in their board risk committees. The Federal Reserve’s EPS requires that the risk committee include at least one independent director, while the US OCC regulations increased the required number to two independent directors.

The survey found that the trend towards independent directors on the board risk committee has become pronounced. Forty-five per cent of institutions reported that their board risk committee includes two or more independent directors (as well as other directors), while 36 per cent said it is composed entirely of independent directors (figure 8). Only 5 per cent of institutions said their board risk committee contains only one independent director, while at 13 per cent of institutions the risk committee does not contain any independent directors.

Having the risk committee chaired by an independent director and having the participation of a risk management expert are becoming regulatory expectations for larger institutions. Many institutions find that in practise it is easier to have independent directors as members of their risk committee, or even be chaired by an independent director, than to secure the participation of an identified risk management expert. Seventy-two per cent of institutions reported that their board risk committee is chaired by an independent director, while 67 per cent have a risk management expert on their committee.

Having an identified risk management expert is most common in the United States/Canada (78 per cent), Asia Pacific (72 per cent), and Latin America (86 per cent) and is less common in Europe (52 per cent). One reason for the lower prevalence in Europe is that European regulations contain a more general requirement that risk committee members “... shall have appropriate knowledge, skills and expertise to fully understand and monitor the risk strategy and the risk appetite of the institution.”42

Role of the CRO

Having an independent risk management function headed by a CRO is a regulatory expectation. The Basel Committee guidance on governance recommends that large banks and internationally active banks have a risk management function and a CRO position with “sufficient authority, stature, independence, resources and access to the board.” 43

Adoption of a CRO position is almost universal, with 92 per cent of institutions reporting that they have a CRO or equivalent position. The CRO position is more common at institutions in the United States/Canada (89 per cent) and Europe (92 per cent) than in Asia Pacific (73 per cent) or Latin America (63 per cent).

There are significant benefits and a general regulatory expectation, for the CRO to report directly to the board of directors as well as to the CEO, but this is not the case at many institutions. The CRO reports to the board of directors at 52 per cent of the institutions surveyed, up slightly from 48 per cent in 2014. Further, the CRO reports to the CEO at 75 per cent of institutions, meaning that at one quarter of the institutions the CRO does not report to the most senior management executive in the organisation. It appears that many institutions have more work to do to improve the reporting structure for their CRO.

At 90 per cent of institutions, the CRO meets regularly with the board of directors or board committees responsible for risk management, although fewer (53 per cent) reported that their CRO meets in executive sessions with the board. Affording the CRO the opportunity to meet with the board of directors or the board risk committee without the CEO or other members of senior management present can provide the board with an opportunity to receive a frank assessment of the state of the risk management programme and the specific challenges the institution faces.

Latin American institutions were least likely to say their CRO reports to the board of directors (14 per cent), compared to 50 per cent or greater in other regions and 52 per cent of Latin American institutions said their CRO reports to the CEO, while this figure is more than two-thirds in other regions. Twenty-nine per cent of respondents at Latin American institutions said the CRO reports to the CFO, while this is the case with less than 10 per cent of institutions in other regions.

It is a leading practise for the CRO to be the most senior management position responsible for the risk management programme, but the CRO does not universally have this role. Only 48 per cent of institutions reported that the CRO or equivalent is the highest level of management responsible for the risk management programme, similar to the percentage in 2014. Other common responses were the CEO (27 per cent), the executive-level risk committee (16 per cent), or the CFO (4 per cent). Assigning primary responsibility for risk management to the CRO is more common among institutions in the United States/Canada (78 per cent) than in Europe (50 per cent), Asia Pacific (38 per cent), or Latin America (25 per cent).

Institutions assign a broad range of responsibilities to the firm-wide, independent risk management group headed by the CRO. Many oversight activities were nearly universal including develop and implement the risk management framework, methodologies, standards, policies and limits (94 per cent), identify new and emerging risks (94 per cent) and develop risk information reporting mechanisms (94 per cent).

However, a number of other important oversight activities are in place at no more than two-thirds of institutions including provide input into business strategy development and the periodic assessment of the plan (65 per cent) and participate in day-to-day business decisions that impact the risk profile (63 per cent). Risk management considerations need to be infused into both strategy and business decisions to consider their risk implications and more progress still needs to be made in these areas.

Another area that a relatively low percentage of respondents said was a responsibility of the risk management programme was approve new business or products (58 per cent). This may be partly explained by the fact that relatively few new products are being introduced in the current economic and regulatory environment.

Finally, regulators and industry leaders have devoted considerable attention to the role that incentive compensation and culture play in risk management, yet the activity review compensation plan to assess its impact on risk appetite and culture was identified as a responsibility by 54 per cent of respondents. This was more often a risk management responsibility at institutions in the United States/Canada (75 per cent) and Europe (62 per cent) than in Asia Pacific (38 per cent) and Latin America (43 per cent).

Risk appetite

A written risk appetite statement provides guidance for senior management when setting an institution’s strategic objectives and for lines of business when making business decisions. The idea of a risk appetite has been around for some time but has received renewed attention since the global financial crisis. The FSB issued principles for an effective risk appetite framework in November 2013. 44 In 2015, the Basel Committee issued guidance that stressed the role of the board of directors in establishing, along with senior management and the CRO, the institution’s risk appetite. 45

There is now wide adoption of a written, enterprise-level risk appetite statement approved by the board of directors. Eighty-five per cent of institutions reported they have such a statement approved by the board of directors, up from 75 per cent in 2014. The regulatory focus on risk appetite began in banking, where 91 per cent reported either having a risk appetite statement approved by their board of directors or being in the process of developing a statement and securing approval. But risk appetite statements have now also become common in investment management firms (83 per cent) and insurance companies (85 per cent).

There are challenges in developing a risk appetite statement that provides useful guidance to the business. Respondents most often said that it is extremely or very challenging to define risk appetite for newer risk types such as reputational risk (49 per cent), strategic risk (48 per cent), model risk (48 per cent) and cybersecurity risk (46 per cent) (figure 9). Each of these risk types poses challenges in defining and measuring risk. For example, strategic risk requires an assessment of the risk posed by an institution’s business strategy, while reputational risk is typically a secondary risk that results from market, credit, operational, or other types of risk events that spread to have wider impacts to the organisation and is thus difficult to measure and establish limits for.

Operational risk has been an area where many institutions had struggled to develop appropriate analytical approaches that would allow them to measure and set risk limits. However, more attention has been paid to this area and it appears that progress is being made. Twenty-seven per cent of respondents said that defining risk appetite for operational risk is extremely or very challenging, down from 38 per cent in 2014.

In contrast, the issues that were least often seen as extremely or very challenging were defining risk appetite for traditional risk types such as liquidity risk (12 per cent), market risk (10 per cent) and credit risk (7 per cent). Institutions generally have many years of experience in these areas and have developed data and analytical methods that allow them to quantify the risk and set appropriate risk limits.

Respondents at European institutions were more likely than those in other regions to say that a number of issues were extremely or very challenging including defining risk appetite forstrategic risk (58 per cent compared to 38 per cent in United States/Canada) and defining risk appetite for reputational risk (63 per cent compared to 38 per cent in United States/Canada and 36 per cent in Asia Pacific). On the other hand, defining risk appetite for operational risk was more often seen as extremely or very challenging by institutions in the United States/Canada (50 per cent) and Latin America (43 per cent) than those in Europe (24 per cent) and Asia Pacific (19 per cent).

It is also challenging to further allocate and delegate risk appetite from the overall risk appetite statement down to risk limits in the various operations and business unit activities of an institution. In some institutions, the development of risk appetite allocations and delegations to business units remains a work in progress as more granular measures are developed. Other important activities were less often considered to be extremely or very challenging but still pose difficulties for many institutions such as allocating the risk appetite among different business units (38 per cent), translating the risk appetite for individual risk types into quantitative risk limits (37 per cent) and integrating risk appetite with stress testing including defining risk appetite for stressed conditions (34 per cent).

— Chief risk officer, large financial services company

Three lines of defence risk governance model

A “three lines of defence” risk governance model is a regulatory expectation and has been accepted as a leading practise so that business units, the risk management programme and internal audit each play their appropriate role in risk management. The three lines of defence model comprises the following components:

- Line 1: Business units own and manage their risks

- Line 2: Independent risk function provides oversight and challenge

- Line 3: Internal audit function validates the risk and control framework

The three lines of defence model is now essentially universally adopted, with all the institutions participating in the survey reporting that they employ it.

Although this model is conceptually sound, practical implementation can present difficulties, especially in large institutions with multiple business units and locations. For a start, an institution needs to have enough skilled personnel in each line of defence. The industry-wide competition for experienced risk management professionals has made it more difficult to hire employees with risk management skills. Business units in particular may find it difficult to attract professionals who have experience both in risk management and also in the business. In fact, having sufficient skilled personnel in all three lines of defence (64 per cent) was the issue most often considered to be a significant challenge in implementing the three lines of defence risk governance model.

The other issues rated as significant challenges revolved around the business units (Line 1) and their interaction with risk management (Line 2). The issue cited next most often as extremely or very challenging was defining and maintaining the distinction in roles between Line 1 (the business) and Line 2 (risk management) (55 per cent, up from 51 per cent in 2014). Business units need to buy into the process and have good collaboration with the risk management function. Too often the three lines of defence model can result in duplication of controls and reviews across the three lines (resulting in so-called “checkers checking the checkers”), and eliminating this redundancy requires clarifying the roles and responsibilities of each group involved.

A third issue cited frequently as extremely or very challenging was getting buy-in from Line 1 (the business) (44 per cent up from 36 per cent in 2014). The business unit executives in Line 1 need to assume responsibility for risk in their daily activities, rather than simply delegating risk management to specific personnel in “risk” roles. Business units need to ensure that material risks associated with their activities are assessed and that there are adequate control mechanisms to manage them, including compliance and conduct testing processes, quality assurance procedures and problem escalation processes.

Yet, getting buy-in from business units can be difficult since business units are measured on the revenue generated rather than specifically on risk management activities. Overcoming this resistance requires instilling a culture throughout the organisation that communicates that identifying and managing risks is an important responsibility of the businesses.

There is a longer tradition of employing the three lines of defence model in the United States/Canada and Europe, which was reflected in the survey. For example, having sufficient skilled personnel in all three lines of defence was more often cited as extremely or very challenging by respondents at institutions in Asia Pacific (77 per cent) and Latin America (75 per cent) than those in United States/Canada (56 per cent) or Europe (46 per cent). Similarly, respondents less often considered getting buy-in from Line 1 (the business) to be extremely or very challenging for the United States/Canada (44 per cent) and Europe (42 per cent) than in Latin America (63 per cent). On the other hand, institutions in the United States/Canada are still struggling with defining and maintaining the distinction in roles between Line 1 (the business) and Line 2 (risk management), where 78 per cent rated it as extremely or very challenging compared to less than 60 per cent in other regions.

Institutions have taken different approaches to the three lines of defence model, with some centralising more activities and others decentralising more activities into the business units. One of the decisions that institutions need to make is where to locate the enterprise control testing function of the risk and control framework. Institutions that take a more decentralised approach have, in effect, split Line 1 into business unit risk management activities (Line 1A) and testing activities (Line 1B), with Line 2 handling monitoring, policy and challenge, and Line 3 conducting additional testing. However, this can lead to redundancy in the testing programme.

A strict interpretation of the three lines of defence model would suggest that the testing function should be centralised in internal audit (Line 3), but this is only the case at 31 per cent of institutions. The remaining institutions take a variety of approaches: embedded within the second line of defence centralised control testing function (23 per cent), performed in various functions (20 per cent), embedded within the second line of defence risk team (17 per cent) and embedded within the first line of defence in the business unit (7 per cent).

A similar organisational challenge is presented by specific risk types. For management of each risk type (or “stripe”), should there be executive accountability where a single individual is responsible for oversight of the risk across the organisation or should responsibility be decentralised to individual business units? Most institutions have a single individual accountable for risk oversight of traditional risk types such as liquidity risk (76 per cent), regulatory/compliance risk (76 per cent), market risk (75 per cent) and credit risk (72 per cent). Banks are more likely to have a single individual accountable for these traditional risk types—liquidity (87 per cent), regulatory/compliance (84 per cent), market (89 per cent) and credit (81 per cent)—compared to less than 80 per cent for investment management firms and insurance companies. This established executive accountability is logical, given the greater regulatory focus on bank risk management programmes.

Substantial majorities of institutions also have a single individual accountable for cybersecurity risk (67 per cent) and operational risk (65 per cent). Cybersecurity risk has received increased attention recently and 100 per cent of the institutions in the United States/Canada reported having a single individual responsible compared to fewer in Europe (62 per cent), Asia Pacific (60 per cent) and Latin America (75 per cent). The risk where oversight is least likely to be centralised is third-party risk, where 44 per cent of institutions have a single individual accountable for oversight, including just 26 per cent of European institutions and only 32 per cent of insurance companies.

Our focus has been on simplifying the operating model for operational risk, pushing more accountability into the true front line and making sure that we don't have redundant effective challenge functions.

— Senior risk executive, large diversified financial services company

Enterprise risk management

An ERM programme is designed to create an overall process to identify and manage risks facing an institution. Establishing an enterprise-wide programme helps prevent important risks from being overlooked, identifies interrelationships among risks in different lines of business or geographic areas and aligns risk utilisation with the organisation’s risk appetite. Regulatory authorities are encouraging financial institutions to implement ERM programmes and leverage their insights when setting business strategy or making important business decisions.

The adoption of ERM programmes is widespread, with 73 per cent of institutions reporting they have an ERM programme. In addition, another 13 per cent of institutions said they are currently implementing an ERM programme, while 6 per cent said they plan to create one in the future.

ERM programmes are more common in the United States/Canada (89 per cent) and Europe (81 per cent), where this has been a focus of regulatory authorities, than in Asia Pacific (69 per cent) or Latin America (38 per cent). However, 50 per cent of the respondents at institutions in Latin America said their institution is currently implementing an ERM programme.

The ERM framework and policy are fundamental documents governing risk management in an institution and should be reviewed and approved by the board of directors or the board risk committee and this now occurs at almost all institutions. Ninety-one per cent of institutions reported having an ERM framework and/or policy that has been approved by the board of directors, indicating the maturity of the large majority of ERM programmes. The board role in approving the ERM framework and/or policy is less common in Latin America (71 per cent) than in the United States/Canada (100 per cent), Europe (95 per cent) and Asia Pacific (91 per cent).

Institutions have a wide range of priorities for their risk management programmes over the next two years. Two of the issues rated frequently by respondents as extremely or very high priorities involved IT systems and data: enhancing risk information systems and technology infrastructure (78 per cent) and enhancing the quality, availability and timeliness of risk data (72 per cent) (figure 10).

What we need to do over the next two years or so, is consolidation of those practises, streamlining of processes that will enhance effectiveness of the risk management organisation.

— Chief risk officer, large diversified financial services company

Another issue considered to be an extremely or very high priority by a substantial majority of respondents was collaboration between the business units and the risk management function (74 per cent), which is essential to having an effective three lines of defence model. This result is consistent with the fact that 55 per cent of respondents said that defining and maintaining the distinction in roles between Line 1 (the business) and Line 2 (risk management) was a significant challenge in implementing the three lines of defence risk governance model. (See the section “three lines of defence risk governance model.”)

With the increase in regulatory requirements, financial services institutions have expanded their risk management personnel both in the risk management function and in business units, and as a result the competition for these professionals has been intense. Seventy per cent of respondents said that attracting and retaining risk management professionals with required skills would be an extremely or very high priority for their institution.

Reflecting the fact that regulatory authorities have increased their attention to the importance of instilling a risk management culture, 70 per cent of respondents cited establishing and embedding the risk culture across the enterprise as a high priority.